Metropolitan Museum of Art

| |

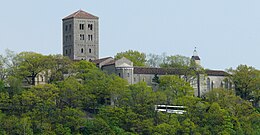

Entrance façades to The Met Fifth Avenue and The Cloisters | |

| |

| Established | April 13, 1870[2][3][4] |

|---|---|

| Location | 1000 Fifth Avenue (The Met Fifth Avenue) 99 Margaret Corbin Drive (The Cloisters) New York City, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 40°46′46″N 73°57′47″W / 40.7794°N 73.9631°W |

| Type | Art museum |

| Collection size | 2 million[1] |

| Visitors | 5.364 million (2023)[5] |

| Chairs | |

| Director | Max Hollein |

| Website | www |

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, colloquially referred to as the Met,[a] is an encyclopedic art museum in New York City. It is the largest art museum in the Americas and the fourth-largest in the world. With 5.36 million visitors in 2023, it is the most-visited museum in the United States and the fourth-most visited art museum in the world.[6]

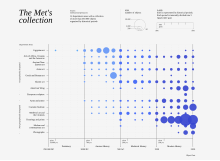

As of 2000, its permanent collection had over two million works;

The Metropolitan Museum of Art was founded in 1870 with its mission to bring art and art education to the American people. The museum's permanent collection consists of works of art ranging from the

Collections

The Met's permanent collection is curated by seventeen separate departments, each with a specialized staff of

Geographically designated collections

Ancient Near Eastern art

Beginning in the late 19th century, the Met started acquiring ancient art and artifacts from the

Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas

Though the Met first acquired a group of

Today, the Met's collection contains more than 11,000 pieces from

The Wing exhibits the arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas in an exhibition separated by geographical locations. The collection ranges from 40,000-year-old

Curator of African Art Susan Mullin Vogel discussed a famous Benin artifact acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1972. It was originally auctioned in April 1900 by a lieutenant named Augustus Pitt Rivers at the price of 37 guineas.[21]

In December 2021, the Met began its $70 million (~$77.7 million in 2023) renovation of The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing's African, ancient American, and Oceanic art galleries, originally planned to begin in 2020 but now set for completion in 2024. The 40,000 square-feet renovation includes the reinstallation of an exterior glass curtain, which had deteriorated, as well as the galleries in their entirety, which house 3,000 works.[22]

Asian art

The Met's Asian department holds a collection of Asian art, of more than 35,000 pieces,

Egyptian art

Though the majority of the Met's initial holdings of Egyptian art came from private collections, items uncovered during the museum's own archeological excavations, carried out between 1906 and 1941, constitute almost half of the current collection. More than 26,000 separate pieces of Egyptian art from the Paleolithic era through the Ptolemaic era constitute the Met's Egyptian collection, and almost all of them are on display in the museum's massive wing of 40 Egyptian galleries.[28] Among the rarest pieces in the Met's Egyptian collection are 13 wooden models (of the total 24 models found together, 12 models and 1 offering bearer figure is at the Met, while the remaining 10 models and 1 offering bearer figure are in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo), discovered in a tomb in the Southern Asasif in western Thebes in 1920. These models depict, in unparalleled detail, a cross-section of Egyptian life in the early Middle Kingdom: boats, gardens, and scenes of daily life are represented in miniature. William the Faience Hippopotamus is a miniature that has become the informal mascot of the museum. Other notable items in the Egyptian collection include the Chair of Reniseneb, the Lotiform Chalice, and the Metternich Stela.

However, the popular centerpiece of the Egyptian Art department continues to be the

In 2018, the museum built an exhibition around the golden-sheathed 1st-century BCE coffin of Nedjemankh, a high-ranking priest of the ram-headed god Heryshaf of Heracleopolis. Investigators determined that the artifact had been stolen in 2011 from Egypt, and the museum returned it.[31]

European paintings

In 2012 the Met's collection of European paintings numbered "more than 2,500 works of art from the thirteenth through the early twentieth century."[32] As of December 2021, it had 2,625.[33] These paintings are housed in the Old Masters galleries (newly installed in 2023),[34][35] the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century galleries reinstalled in 2007[36][37] (both on the second floor of the main building), the Robert Lehman Collection,[38] and the Jack and Belle Linsky Collection[39] (both on the first floor); a number of paintings also hang in other departmental galleries. Some of the medieval paintings are permanently exhibited at the Met Cloisters.[32] The current curator in charge of the European Paintings department is Stephan Wolohojian.[40]

Old Master paintings

The collection began when 174 paintings were purchased from European dealers in 1871.[32] Almost two-thirds of these paintings have been deaccessioned, but quality paintings by Jordaens, Van Dyck, Poussin, the Tiepolos, Guardi, and some other artists remain in the collection.[41] Major gifts from Henry Gurdon Marquand in 1889, 1890 and 1891[42] gave the Met a much more solid foundation. Additionally, his example helped to create a taste for collecting Old Master paintings. In 1913, the Benjamin Altman bequest had sufficient range and depth to put the Met’s collection of paintings on the map. In 1949, the Jules Bache gift added more great paintings.[43] The Robert Lehman Collection, which came to the museum in 1975, included many significant paintings, and is particularly strong in early Renaissance material. Over a period of decades, Charles and Jayne Wrightsman donated 94 works of unusually high quality to the Department of European Paintings, the last of which came with Mrs. Wrightsman’s bequest in 2019. Notwithstanding the contributions made by Marquand, Altman, Bache, and Lehman, it has been written that "the Wrightsman paintings are highest in overall quality and condition."[44] The latter "collected expertise as well as art," and advanced technology made better choices possible.[44] Additionally, the Wrightsmans had the Met's curators at their disposal, for whom they served as a virtual "auxiliary purchase fund for objects the Met curators coveted, but could not afford."[44]

Plein Air, Impressionist, and Post-Impressionist Paintings

The Met's plein air painting collection, which it calls "unrivaled,"[45] was the last large section of the European Paintings collection to have a home at the museum. The sale of a Monet and the construction of small scale galleries ultimately resulted in the acquisition of 220 European paintings (most of them plein-air sketches) from two collections. The Monet was used to purchase a half share of Wheelock "Lock" Whitney III's collection in 2003 (the remainder came as a promised gift), and when Eugene V. Thaw (1927-2018) saw how good they looked in the Met's new, purpose built galleries, he and his wife Clare donated their substantially larger collection to the Met (much of it a joint gift to the Morgan Library). The Met easily has the best collection of this material in the nation, and one of the three or four best in the world.[33] Thus the Met’s collection, hitherto top-heavy with famous French artists, "became uniquely diverse," with "many little-known artists from France, as well as numerous artists from other European nations;" many of which are not otherwise represented in U.S. museums.[33] The plein-air collection forms a bridge "to what became the avant-garde," the Impressionists and their successors.[33]

As noted by the museum, "a work by Renoir entered the Museum as early as 1907 (today the Museum has become one of the world's great repositories of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art)."[46] The museum terms its nineteenth-century French paintings "second only to the museums of Paris," with strengths in "Gustave Courbet, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and others."[45]

The foundation of the museum's great Impressionist and Post-Impressionist collection was laid by the Louisine (1855-1929) and Henry Osborne Havemeyer (1847-1907) collection. The most important portion of their immense collection came to the museum after the death of Louisine in 1929.[43][47][48] It was particularly strong in works by Courbet, Corot, Manet, Monet, and, above all, Degas. The other remarkable gift of this material came from Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg, who, before they promised their collection to the Met in 1991, annually loaned it to the Met for half a year at a time.[49][50] Walter Annenberg described his choice of gifting his collection to the Met as an example of "strength going to strength."[51] The two collections are highly complementary: "The Annenberg collection serves as a second, complementary core collection of blue chip Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings. Most importantly, it strengthened the Met’s relatively sparse holdings of Gauguin and Toulouse-Lautrec, it added needed late works by Cézanne and Monet as well as a rare Seurat, and it brought a very impressive group of Van Goghs to a collection already rich in works by the Dutchman."[33]

European sculpture and decorative arts

The European Sculpture and Decorative Arts collection is one of the largest departments at the Met, holding in excess of 50,000 separate pieces from the 15th through the early 20th centuries.

American Wing

The museum's collection of American art returned to view in new galleries on January 16, 2012. The new installation provides visitors with the history of American art from the 18th through the early 20th century. The new galleries encompasses 30,000 square feet (2,800 m2) for the display of the museum's collection.[53] The curator in charge of the American Wing since September 2014 is Sylvia Yount.[54][55]

In July 2018, Art of Native America opened in the American Wing.[56] This marked the first appearance of Indigenous American art in the museum's vast American wing.[57] Art of Native America was accompanied by a statement from the institution. "The American Wing acknowledges the sovereign Native American and Indigenous communities dispossessed from the lands and waters of this region. We affirm our intentions for ongoing relationships with contemporary Native American and Indigenous artists and the original communities whose ancestral and aesthetic items we care for."[56] Contrary to this public statement, the museum came under immense scrutiny for the hazy provenance of the displayed items.[58] This was followed by the hiring of a new curator of Indigenous American art for the museum, Dr. Patricia Marroquin Norby, who is of Purépecha descent.[59]

Greek and Roman art

The Met's collection of Greek and Roman art contains more than 17,000 objects.[60] The Greek and Roman collection dates back to the founding of the museum—in fact, the museum's first accessioned object was a Roman sarcophagus, still currently on display.[61] Though the collection naturally concentrates on items from ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, these historical regions represent a wide range of cultures and artistic styles, from classic Greek black-figure and red-figure vases to carved Roman tunic pins.[62]

Highlights of the collection include the monumental Amathus sarcophagus and a magnificently detailed Etruscan chariot known as the "Monteleone chariot". The collection also contains many pieces from far earlier than the Greek or Roman empires—among the most remarkable are a collection of early Cycladic sculptures from the mid-third millennium BCE, many so abstract as to seem almost modern. The Greek and Roman galleries also contain several large classical wall paintings and reliefs from different periods, including an entire reconstructed bedroom from a noble villa in Boscoreale, excavated after its entombment by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE. In 2007, the Met's Greek and Roman galleries were expanded to approximately 60,000 square feet (6,000 m2), allowing the majority of the collection to be on permanent display.[63]

The Met has a growing corpus of digital assets that expand access to the collection beyond the physical museum. The interactive Met map provides an initial view of the collection as it can be experienced in the physical museum. The Greek and Roman Art department page provides a department overview and links to collection highlights and digital assets. The Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History provides a one thousand year overview of Greek art from 1000 BCE to 1 CE. More than 33,000 Greek and Roman objects can be referenced in the Met Digital Collection via a search engine.

Islamic art

The Metropolitan Museum owns one of the world's largest collection of works of art of the Islamic world. The collection also includes artifacts and works of art of cultural and secular origin from the time period indicated by the rise of Islam predominantly from the Near East and in contrast to the Ancient Near Eastern collections. The biggest number of miniatures from the "Shahnameh" list prepared under the reign of Shah Tahmasp I, the most luxurious of all the existing Islamic manuscripts, also belongs to this museum. Other rarities include the works of Sultan Muhammad and his associates from the Tabriz school "The Sade Holiday", "Tahmiras kills divs", "Bijan and Manijeh", and many others.[64]

The Met's collection of

Islamic Arts galleries had been undergoing refurbishment since 2001 and reopened on November 1, 2011, as the New Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia. Until that time, a narrow selection of items from the collection had been on temporary display throughout the museum. As with many other departments at the Met, the Islamic Art galleries contain many interior pieces, including the entire reconstructed Nur Al-Din Room from an early 18th-century house in Damascus.[67]

In September 2022 the Met revealed that it had received a substantial gift from Qatar Museums on the occasion of its 10th anniversary of the opening of its Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia and Later South Asia, which would benefit its Department of Islamic Art and some of the museum's other principal projects. As a token of its appreciation the name Qatar Gallery was adopted for the museum's Gallery of the Umayyad and Abbasid Periods.[68][69] This followed the announcement that the Met and Qatar Museums had entered into a partnership to foster their exchange with regards to exhibitions, activities, and scholarly cooperation.[70]

Non-geographically designated collections

Arms and armor

The Met's Department of Arms and Armor is one of the museum's most popular collections.[71] Several early trustees of the museum were armor enthusiasts. The 1904 purchase of the collection of Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, duc de Dino, served as the foundational collection. It became a great collection with the gift and bequest of the Henry Riggs collection of 2,000 pieces, which was one of the finest assembled by a single person. It came to the museum in 1913 and 1925. Another collection landmark took place in 1936, when George Cameron Stone bequeathed 3,000 pieces of Asian armor. Bashford Dean, the first arms curator, did much to build up the collection, including with gifts he and his friends made directly to the Met, which enabled the purchase of his personal collection.[43][72][73]

Stephen V. Grancsay, the second arms curator at the museum, ably added to the collection, and he even purchased important works from Clarence H. Mackay (the greatest contemporary private collector of this material, who was wiped out by the Great Depression). Grancsay later resold some of these important works to the museum at cost.[72]

The department's focus on "outstanding craftsmanship and decoration," including pieces intended solely for display, means that the collection is strongest in

The distinctive "parade" of armored figures on horseback installed in the first-floor Arms and Armor gallery is one of the most recognizable images of the museum, which was organized in 1975 with the help of the Russian immigrant and arms and armor scholar, Leonid Tarassuk (1925–90).

In 2020 the Met announced Ronald S. Lauder's promised gift of 91 objects from his collection, describing it as "the most significant grouping of European arms and armor given to the Museum since 1942," one that is "outstanding for the exceptional rarity and quality of the objects, their illustrious origins, and their typological variety."[76] Lauder, who noted that he had begun collecting with the assistance of curator Grancsay almost 55 years earlier, also donated money for the study and presentation of arms and armor. The 11 galleries were named in Lauder's honor.

Costume Institute

The Museum of Costume Art was founded by

In past years, Costume Institute shows organized around designers such as

Drawings and prints

Though other departments contain significant numbers of drawings and prints, the Drawings and Prints department specifically concentrates on North American pieces and Western European works produced after the Middle Ages. The first gift of Old Master drawings, comprising 670 sheets, was presented as a single group in 1880 by Cornelius Vanderbilt II, though most proved to be misattributed.[72] The Vanderbilt gift launched the collection, and the Department of Paintings also eventually acquired drawings (including by Michelangelo and Leonardo). In the meantime, the Met library began to collect prints. Harris Brisbane Dick's donation of thirty-five hundred works on paper (mostly nineteenth-century etchings) and a fund for acquisitions led to the hiring of William M. Ivins Jr. in 1916.[92][72]

As the museum's first curator of prints, Ivans established the mission of collecting images that would reveal "the whole gamut of human life and endeavor, from the most ephemeral of courtesies to the loftiest pictorial presentation of man’s spiritual aspirations." Over the next 30 years, he built what is credited as the best collection in the nation.[93] Ivans opened three galleries and a study room in 1971. He curated almost sixty exhibitions, and his influential publications included How Prints Look (1943) and Prints and Visual Communication (1953), in addition to almost two hundred articles for the museum's Bulletin.[73] Ivans and his successor A. Hyatt Mayor (hired 1932, 1946-66 Curator of Prints) collected hundreds of thousands of works, including photographs, books, architectural drawings, modern artworks on paper, posters, trade cards, and other ephemera.[92] Important early donors to the department include: Junius Spencer Morgan II, who presented a broad range of material, mainly 16th century, including woodblocks and many prints by Albrecht Dürer in 1919; Gothic woodcuts and Rembrandt etchings from the Felix M. Warburg family; James Clark McGuire’s transformative bequest brought over seven hundred fifteenth-century woodcuts; prints by Rembrandt, Edgar Degas, and Mary Cassatt with the H.O. Havemeyer Collection in 1929. Ivans also purchased five albums from the auction of the Earl of Pembroke’s collection, and the 2,200 prints in these albums provided a nucleus of Italian prints.[73][92]

Meanwhile, acquisitions of drawings, including an album of 50 Goyas (thanks to Ivans, the Met collected almost 300 works by Goya on paper) continued to be processed through the Department of Paintings. In 1960, a Department of Drawings was established under Jacob Bean, who served as curator until 1992, during which time the museum's collection of drawings nearly doubled in size, with strengths in French and Italian works.[73][94]

Finally, in 1993, a unified Department of Drawings and Prints was created for all works on paper, chaired by George Goldner, who sought to rectify collecting imbalances by adding works by Dutch, Flemish, Central European, Danish, and British artists. The department has been led by Nadine Orenstein, Drue Heinz Curator in Charge since 2015. A particularly important recent gift was that of the Leslie and Johanna Garfield Collection of British Modernism in 2019.[92]

The broadened collecting horizons of the museum in the post-Black Lives Matter era have been displayed in the exhibition of contemporary political works on paper called "Revolution, Resistance, and Activism," held at the Met in 2021-22. It included such works as the Guerrilla Girls' famous poster Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?, 1987, Julie Torres’ Super Diva!, 2020 (a posthumous image of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg), and Ben Blount’s Black Women’s Wisdom, 2019.[95]

Currently, the Drawings and Prints collection contains about 21,000 drawings, 1.2 million prints, and 12,000 illustrated books made in Europe and the Americas.[96] Many of the great masters of European painting, who produced many more sketches and drawings than actual paintings, are represented in the Drawing and Prints collection, sometimes in great concentrations. Prints are also represented in multiple states. Many artists and makers whose work is in the prints and drawings collection are otherwise not represented in the museum's holdings.

Robert Lehman Collection

On the death of banker Robert Lehman in 1969, his Foundation donated 2,600 works of art to the museum, which had been collected by Robert and his father.[97] Housed in the "Robert Lehman Wing", on the ground floor and the basement level, the museum refers to the collection as "one of the most extraordinary private art collections ever assembled in the United States".[98] To emphasize the personal nature of the Robert Lehman Collection, the Met housed the collection in a special set of galleries, some of which evoked the interior of Lehman's richly decorated townhouse at 7 West 54th Street. This intentional separation of the Collection as a "museum within the museum" met with mixed criticism and approval at the time, though the acquisition of the collection was seen as a coup for the Met.[99] Some have argued that it would be educationally more beneficial to have works from given schools of painting in the same section of the museum.

Unlike other departments at the Met, the Robert Lehman collection does not concentrate on a specific style or period of art; rather, it is a reflection of Lehman's personal collecting interests. The Lehmans concentrated heavily on paintings of the

Lehman's collection of 700 drawings by the

The collection of bronzes, furniture, Renaissance majolica, Venetian glass, enamels, jewelry, textiles, and frames is outstanding.[104] The Lehman collection of Italian majolica is regarded as the best in the country.[105]

Robert Lehman also collected many nineteenth and twentieth century paintings. These include works by Ingres, Corot, the Barbizon School, Monet, Renoir, Cezanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Seurat, and a number of Fauve painters, including Matisse.[106] Princeton University Press has documented the massive collection in a multi-volume book series published as The Robert Lehman Collection Catalogues.[107]

Medieval art and the Cloisters

The Met's collection of medieval art consists of a comprehensive range of Western art from the 4th through the early 16th centuries, as well as Byzantine and pre-medieval European antiquities not included in the Ancient Greek and Roman collection. Like the Islamic collection, the Medieval collection contains a broad range of two- and three-dimensional art, with religious objects heavily represented. In total, the Medieval Art department's permanent collection numbers over 10,000 separate objects, divided between the main museum building on Fifth Avenue and The Cloisters.[108]

Main building

The medieval collection in the main Metropolitan building, centered on the first-floor medieval gallery, contains about 6,000 separate objects. While a great deal of European medieval art is on display in these galleries, most of the European pieces are concentrated at the Cloisters (see below). However, this allows the main galleries to display much of the Met's Byzantine art side by side with European pieces. The main gallery is host to a wide range of tapestries and church and funerary statuary, while side galleries display smaller works of precious metals and ivory, including reliquary pieces and secular items. The main gallery, with its high arched ceiling, also serves double duty as the annual site of the Met's elaborately decorated Christmas tree.[109]

The Cloisters museum and gardens

The Cloisters was a principal project of John D. Rockefeller Jr., a major benefactor of the Met. Located in Fort Tryon Park and completed in 1938, it is a separate building dedicated solely to medieval art. The Cloisters collection was originally that of a separate museum, assembled by George Grey Barnard and acquired in toto by Rockefeller in 1925 as a gift to the Met.[110]

The Cloisters are so named on account of the five medieval French

Modern and contemporary art

With some 13,000 artworks, primarily by European and American artists, the modern art collection occupies 60,000 square feet (6,000 m2), of gallery space

In April 2013, it was reported that the museum was to receive a collection worth $1 billion (~$1.29 billion in 2023) from cosmetics tycoon Leonard Lauder. The collection of Cubist art includes work by Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Juan Gris and went on display in 2014.[118] The Met has since added to the collection, for example spending $31.8 million (~$38 million in 2023) for Gris' The musician's table in 2018.[119]

Musical instruments

The Met's collection of musical instruments, with about 5,000 examples of musical instruments from all over the world, is virtually unique among major museums.[120] The collection began in 1889 with a donation of 270 instruments by Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown, who joined her collection to become the museum's first curator of musical instruments, named in honor of her husband, John Crosby Brown.[121] By the time she died, the collection had 3,600 instruments that she had donated and the collection was housed in five galleries. Instruments were (and continue to be) included in the collection not only on aesthetic grounds, but also insofar as they embodied technical and social aspects of their cultures of origin. The modern Musical Instruments collection is encyclopedic in scope; every continent is represented at virtually every stage of its musical life. Highlights of the department's collection include several Stradivari violins, a collection of Asian instruments made from precious metals, and the oldest surviving piano, a 1720 model by Bartolomeo Cristofori. Many of the instruments in the collection are playable, and the department encourages their use by holding concerts and demonstrations by guest musicians.[122]

Photographs

The Met's collection of

The department of photography was founded in 1992. Though the department gained a permanent gallery in 1997, not all of the department's holdings are on display at any given time, due to the sensitive materials represented in the photography collection. However, the Photographs department has produced some of the best-received temporary exhibits in the Met's recent past, including a Diane Arbus retrospective and an extensive show devoted to spirit photography. In 2007, the museum designated a gallery exclusively for the exhibition of photographs made after 1960.[125]

Film

The Met has an extensive archive consisting of 1,500 films made and collected by the museum since the 1920s. As part of the museum's 150 anniversary commemoration, since January 2020, the museum uploads a film from its archive weekly onto YouTube.[126]

Digital representation of collections

Beginning in 2013, the Met organized the Digital Media Department for the purpose of increasing access of the museum's collections and resources using digital media and expanded website services. The first Chief Digital Officer

In May 2022, the Met and the World Monuments Fund announced a collaboration of digital work for the 2024 reopening of the African, ancient American, and Oceanic art galleries. The digital project "aims to bolster the understanding of several historic sites in sub-Saharan Africa", in particular sites that have been minimally explored by Western museums.[129]

Open access images and data have been viewed over 1.2 billion times with over 7 million downloads.[130]

Libraries

Each Department maintains a library, most of the material of which can be requested online through the libraries' catalog.[131] Two of the libraries may be accessed without an appointment:

Thomas J. Watson Library

The Thomas J. Watson Library is the central library of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and supports the activities of staff and researchers. Watson Library's collection contains approximately 900,000 volumes, including monographs and exhibition catalogs; over 11,000 periodical titles; and more than 125,000 auction and sale catalogs.[132] The library includes a reference collection, auction and sale catalogs, a rare book collection, manuscript items, and vertical file collections. The library is accessible to anyone 18 years of age or older simply by registering online and providing a valid photo ID.[133]

Nolen Library

The Nolen Library is open to the general public. The collection of some 8,000 items, arranged in open shelves, includes books, picture books, DVDs, and videos. The Nolen Library includes a children's reading room and materials for teachers.[134]

Special exhibitions

The museum regularly hosts notable special exhibitions, often focusing on the works of one artist that have been loaned out from a variety of other museums and sources for the duration of the exhibition. These exhibitions are part of the attraction that draw people both within and outside Manhattan to explore the Met. Such exhibitions include displays especially designed for the Costume Institute, paintings from artists from across the world, works of art related to specific art movements, and collections of historical artifacts. Exhibitions are commonly located within their specific departments, ranging from American decorative arts, arms and armor, drawings and prints, Egyptian art, Medieval art, musical instruments, and photographs. Typical exhibitions run for months at a time and are open to the general public. Each exhibition provides insight into the world of art as a transformative, cultural experience and often includes a historical analysis to demonstrate the profound impact that art has on society and its dramatic transformation over the years.[135]

In 1969, a special exhibition, titled "Harlem on My Mind" was criticized for failing to exhibit work by Harlem artists. The museum defended its decision to portray Harlem itself as a work of art.[136] Norman Lewis, Benny Andrews, Romare Bearden, Clifford Joseph, Roy DeCarava, Reginald Gammon, Henri Ghent, Raymond Saunders, and Alice Neel were among the artists who picketed the show.[137]

In America: An Anthology of Fashion

In America: An Anthology of Fashion is the 2022

History

19th century

The

The museum first opened on February 20, 1872, housed in a building located at 681 Fifth Avenue.[143] John Taylor Johnston, a railroad executive whose personal art collection seeded the museum, served as its first president, and the publisher George Palmer Putnam came on board as its founding superintendent. The artist Eastman Johnson acted as co-founder of the museum,[144] as did landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church.[145] Various other industrialists, artists, and scientists of the age served as co-founders, including Howard Potter, Salem Howe Wales, and Henry Gurdon Marquand. Marquand's donated works are known as the Marquand Collection.[42] The former Civil War officer, Luigi Palma di Cesnola, was named as its first director. He served from 1879 to 1904. Under their guidance, the Met's holdings, initially consisting of a Roman stone sarcophagus and 174 mostly European paintings, quickly outgrew the available space. In 1873, occasioned by the Met's purchase of the Cesnola Collection of Cypriot antiquities, the museum decamped from Fifth Avenue and took up residence at the Mrs. Nicholas Cruger Mansion also known as the Douglas Mansion (James Renwick, 1853–54, demolished 1928) at 128 West 14th Street.[146] However, these new accommodations proved temporary, as the growing collection required more space than the mansion could provide.[147] It moved into the current building in 1880. Between 1879 and 1895, the museum created and operated a series of educational programs, known as the Metropolitan Museum of Art Schools, intended to provide vocational training and classes on fine arts.[148]

20th century

The museum is said to have established the world's first

In the 1960s, the governance of the Met was expanded to include, for the first time, a chairman of the board of trustees in contemplation of a large bequest from the estate of Robert Lehman. For six decades Lehman built upon an art collection begun by his father in 1911 and devoted a great deal of time the Met, before finally becoming the first chairman of the board at the Metropolitan in the 1960s.[152] After his death in 1969, the Robert Lehman Foundation donated close to 3,000 works of art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Housed in the Robert Lehman Wing, which opened to the public in 1975 and largely financed by the Lehman Foundation, the museum has called it "one of the most extraordinary private art collections ever assembled in the United States".[153]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Centennial was celebrated with exhibitions, symposia, concerts, lectures, the reopening of refurbished galleries, special tours, social events, and other programming for eighteen months from October 1969 through the spring of 1971. The centennial's events (including an open house, Centennial Ball, year-long art history course for the public, and various educational programming and traveling exhibitions) and publications drew on support from prominent New Yorkers, artists, writers, composers, interior designers, and art historians.[154]

21st century

In 2009 Michael Gross published The Secret History of the Moguls and the Money That Made the Metropolitan Museum, an unauthorized social history,[155] and the museum bookstore declined to sell it.[156][157]

In 2012, following the earlier appointment of Daniel Brodsky as chairman of the board at the Met, the by-laws of the museum were formally amended to recognize the office of the chairman as having authority over the assignment and review of both the offices of president and director of the museum.[158] The office of chairman was first introduced relatively late in the museum's history in the 1960s in contemplation of the anticipated donation of the Lehman collection to the museum and has since that time, under Brodsky, become the most senior administrative position at the museum.[158]

From 2016 to 2020, the museum operated a modern and contemporary art gallery at

In January 2018, museum president Daniel Weiss announced that the century-old policy of free admission would be replaced by a $25 charge to out-of-state and foreign visitors, effective March 2018.[164] The museum temporarily closed in March 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City, and reopened in late August;[165] this was the first time in over a century that the Met was closed for more than three consecutive days.[166]

In September 2020, following debates surrounding provenance holes and mismanagement of Indigenous art, the museum appointed Patricia Marroquin Norby (Purépecha/Nde descent) as the museum's inaugural Associate Curator of Native American Art.[59][167][168] In May 2021, the museum installed a plaque on its Fifth Avenue facade in recognition of indigenous communities and of the fact that the museum is situated in what was historically Lenapehoking.[169][170] That November, the Met received a $125 million donation from Oscar L. Tang and Agnes Hsu-Tang, the largest gift in the museum's history. In exchange, the Met named its modern and contemporary art galleries after the Tangs.[171] The following February, the Met hired Moody Nolan to renovate the Ancient Near Eastern and Cypriot galleries.[172] Mexican architect Frida Escobedo was hired in March 2022 to renovate the Tang wing.[173]

In 2024, several protests targeted the Met for complicity in the

Architecture

After negotiations with the City of New York in 1871, the Met was granted the land between the East Park Drive, Fifth Avenue, and the 79th and

The Met Fifth Avenue measures almost 1⁄4-mile (400 m) long and with more than 2 million square feet (190,000 m2) of floor space, more than 20 times the size of the original 1880 building.[179][180] The museum building is an accretion of over 20 structures, most of which are not visible from the exterior. The City of New York owns the museum building and contributes utilities, heat, and some of the cost of guardianship.[181][182] The Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden is located on the roof near the southwestern corner of the museum.[183][184] The museum's main building was designated a city landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1967,[185] and its interior was separately recognized by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1977.[186] The Met's main building was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1986, recognizing both its monumental architecture, and its importance as a cultural institution.[187]

Management

Governance

Daniel Weiss was the President and CEO of the Met, replacing Emily K. Rafferty, who served as president for a decade,[188] and Thomas P. Campbell, CEO and director of the museum until resigning in 2017. In April 2018, Max Hollein was named director.[189] The Met announced in August 2022 that Hollein became CEO in July 2023.[190]

Board

Although the City of New York owns the museum building and contributes utilities, heat, and some of the cost of guardianship, the collections are owned by a private corporation of fellows and benefactors which totals about 950 people. The museum is governed by a board of trustees of 41 elected members, several officials of the City of New York, and persons honored as trustees by the museum. The current co-chairs of the board,

The activities of board of trustees are organized and based upon the activities of the individual trustees and their various committees as of 2016.[192] The several committees of the board of trustees include the committees listed as Nominating, Executive, Acquisitions, Finance, Investment, Legal, Education, Audit, Employee Benefits, External Affairs, Merchandising, Membership, Building, Technology, and The Fund for the Met.[192]

Finances

As of 2021, the museum's endowment as administered by the museum's investment officer Lauren Meserve

In 2019, museum president Daniel Weiss announced that the institution would review its policy for receiving financial donations, under pressure from activist group P.A.I.N. for the role that cultural institutions have played in whitewashing the Sackler family by receiving their donations.[201] The museum announced it would remove the Sackler name from locations within the museum in December 2021.[202]

2015–2018 setbacks

In September 2016, The Wall Street Journal first reported financial set-backs at the museum related to servicing its outstanding debts and associated cut-backs in staffing at the museum, with the goal of trying to balance its budget by fiscal year 2018.[203] According to the Met's annual tax filing for fiscal year 2016, several top executives had received disproportionately high compensation, often exceeding $1 million per annum with over $100,000 bonuses per annum.[204]

In April 2017,

Brodsky, the chairman of the Met, stated that after the 2017 financial setbacks, the director position would be appointed separately from the position of CEO. Following a commissioned report from the

In January 2018, Pogrebin writing for The New York Times reported that amid-continuing reverberations from "a period of financial turbulence and leadership turmoil" that the museum president Daniel Weiss had announced that the museum would rescind its century-old policy of free admission to the museum and begin charging $25 for out-of-state visitors starting in March 2018.[164] Pogrebin stated that although the museum had made progress in decreasing its deficit from $40 million to $10 million, that an adverse decision from the City of New York to curtail funding for the Met's operating costs by as much as $8 million "for security and building staff" caused Weiss to announce the change in admissions policy. Weiss indicated that the new policy would be estimated to increase revenue from the current $43 million it receives from admissions to an enhanced revenue stream as high as US$49 million.[164]

Attendance

For the fiscal year 2017 which ended on June 30, the museum was reported as having 7 million visitors during the past year, where "37 percent of these were international visitors, while 30 percent came from New York's five boroughs."[209] Previously in 2016, the museum set a record for attendance, attracting 6.7 million visitors—the highest number since the museum began tracking admissions.[210] Forty percent of the Met's visitors in fiscal year 2016 came from New York City and the tristate area; 41 percent from 190 countries besides the United States.[210] In 2017, the attendance figures indicated seven million annual visitors with 63% of the visitors arriving from outside of New York State.[141]

Roberta Smith writing for The New York Times in September 2017 voiced growing public concern that proposed increases in admissions costs would have an adverse effect upon attendance statistics at the museum. Smith referred to the public perception that such costs would appear "greedy and inappropriate" because "The museum already gets around $39 million a year from its gate—equal to the entire annual budget of the Brooklyn Museum."[211] Smith's article continued to report the negative response of local communities in the tristate area surrounding the museum which was previously introduced in a series of articles by Robin Pogrebin written during the 2016–2017 fiscal year at the museum which criticized speculative suggestions among current administrators at the museum that an added revenue stream could be pursued by the museum by rescinding existing museum policy since 1893 allowing for free public access to the museum.[141] In January 2018, museum president Daniel Weiss announced that the century-old policy of free museum admission would be replaced. Effective March 2018, most visitors who do not live in New York state or are not a student from New York, New Jersey, or Connecticut have to pay $25 (~$30.00 in 2023) to enter the museum.[164] The City of New York has reduced funding at the Metropolitan as part of Mayor De Blasio's political effort to increase artistic diversity. They made an agreement to allow the fees in exchange for less funding which the city pledged to use at alternate facilities and promote diversity.[212]

Holland Carter and Roberta Smith of The New York Times argued in response to Weiss's decision to rescind the previous free admission policy as lacking in responsible fiscal planning. They stated that a recent $65 million expenditure for renovating fountains seemed to be a poor allocation of the limited available funding. Smith added, "Those new awful Darth Vaderish fountains take huge chunks out of the plaza and disrupt movement," as an indication of the misuse of funds.[213] Further criticism of Weiss's proposal was voiced internationally when The Guardian summarized the backlash from the Weiss proposal for raising the admissions fees. It stated, "Some critics are outraged. The past week has seen a New York Times piece titled "The New Pay Policy Is a Mistake", while Jezebel's Aimée Lutkin claimed "The Met Should Be Fucking Free". The New York Post writes that the museum has never had the right to charge admission and Alexandra Schwartz in the New Yorker says the new policy diminishes New York City".[214]

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021)

In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic greatly impacted the Met's operations and led to the museum's first long-term shutdown on March 13. The Met gradually partially reopened in stages. By 2021, the public could visit the Met five days a week, with reduced hours of operation, and visitors were required to wear masks and practice social distancing. Several special exhibits were opened to the public during the reduced hours. There were 6,479,548 visitors in 2019, compared to 1,124,759 in 2020.[215] However, in 2021, the museum attracted 1,958,000 visitors, ranking fourth on the list of most-visited art museums in the world.[216]

Other services such as the research libraries were almost completely closed except for off-site digital access. As a result, 20 percent of staff positions were eliminated, and Met director Max Hollein indicated that the Met might deaccession and sell off some of its collection to make up financial shortfalls. At least some of the museum's large art holding was placed in storage in order to make-up for losses in revenue causes by responses to the pandemic.[217]

Deaccessioning Works of Art

The Met has always deaccessioned works to improve the collection by using the proceeds to buy better or more appropriate works. As noted above, it has deaccessioned nearly two-thirds of the founding purchase of Old Master paintings made in 1871.[41] As early as 1887, it sold 5,000 Cypriot objects in order to purchase Egyptian antiquities, and over the years it sold many thousands more works from Cyprus.[147] 15,000 Egyptian objects were sold in the museum's shop in 1955, and nearly 10,000 works from other departments were earmarked that year for sale at auction.[147]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art spent $39 million to acquire art for the fiscal year ending in June 2012.[218] In 2020, it spent $29,824,000 (with $6,747,000 coming from insurance and the sale of art).[219] In 2021, it spent $36,402,000 (with $4,007,000 coming from insurance and the sale of art).[220] In 2022, it spent $74,432,000 (with $9,488,000 coming from insurance and the sale of art); in 2023 it spent $52,401,000 (with $7,444,000 coming from insurance and the sale of art).[221]

In the early 1970s, under the directorship of

Two of the objects purchased with funds generated by Hoving's deaccessions were highlights of the Met's collection.

Hoving was criticized for selling important works from the museum to fund his acquisitions, including a Henri Rousseau and a Van Gogh, and he planned to sell many more, including 14 Monet paintings he characterized as "routine."[33] During the tenure of director Philippe de Montebello, the sale of a single Monet (together with the construction of purpose-built galleries) eventually led to the acquisition of two collections totaling 220 paintings, which established the museum's remarkable plein-air paintings collection.[33]

Another deaccessioning controversy broke out in 2021, when the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) temporarily relaxed its guidelines due to hardships suffered by museums during the COVID pandemic. Previously, funds from deaccessioned works were only to be used to purchase other works for the permanent collection. The temporary guidelines, however, permitted these monies to be used for the "care" of the collection. The Met decided to use funds from deaccessions for collection care (to pay salaries). It was roundly criticized for this decision by the Met's former director Thomas P. Campbell (Montebello's successor), by cultural critic Lee Rosenbaum, and by Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Christopher Knight, among others. They argued that the practice set a bad example for other museums and that the Met did not truly need these monies.[33]

Looted art

One of the most serious and daunting challenges to the Metropolitan Museum's respectable reputation has been a series of allegations and lawsuits about its known status as an institutional buyer of looted and stolen antiquities. Since the 1990s the Met has been the subject of countless investigative reports and books critical of the Met's laissez-faire attitude to acquisition.[225][226] The Met has lost several major lawsuits, notably against the governments of Italy and Turkey, which successfully sought the repatriation of hundreds of ancient Mediterranean and Middle Eastern antiquities, with a total value in the hundreds of millions of dollars.[225] In August 2022, it was reported that the Cambodian government was pressuring the museum to return Khmer artifacts that were allegedly looted during the civil war and the tumultuous period following.[227] In September 2022, New York law enforcement, across three separate search warrants, seized 27 artifacts highlighting ancient Rome, Greece, and Egypt, with the intention of returning them to Italy and Egypt.[228][229] These 27 objects were worth an aggregate total of $13 million.[228] The items were seized due to their discovered link to known antiquities traffickers.[229] This comes along with an international recalculation of what belongs in the museums of the world.[228] Similar cases of repatriation conversations include the Elgin Marbles, the Benin Bronzes, and El Penacho. Along with the conversation about returning art, the art community is calling upon museological institutions to hold themselves to a higher standard of Social Justice, equity, and ethics.[230] On March 22, 2023, Manhattan prosecutors seized 15 allegedly stolen antiquities tied to Subhash Kapoor.[231] In December 2023, the museum announced it will return 14 Khmer sculptures to Cambodia and 2 to Thailand after determining they were stolen and linked to art dealer Douglas Latchford.[232]

Looted Indigenous American art and NAGPRA violations

Since 1993, Charles and Valerie Diker have donated 139 Indigenous objects to the museum, many of which are funerary. Most of these objects have

In April 2023,

Collecting practices

In response to many controversies, the museum issued a statement on collecting practices. The statement encompasses all 1.5 million works of art held by the Met.[237] Referencing research, transparency, and collaboration, this statement is a clear redefining of the Met's outlook on looted art and artwork with unknown histories. “As a pre-eminent voice in the global art community, it is incumbent upon the Met to engage more intensively and proactively in examining certain areas of our collection,” stated Max Hollein, the directer of the museum.[238] The Met hired a manager of provenance research with a team of three staff to assist the already-employed curators and historians.

Selected objects

-

Phoenician metal bowl from 725 to 675 BCE

-

Tabernacle of Cherves, c. 1220–30

-

Scuola di biduino, portale da san leonardo al frigido, vicino massa carrara, Biduino, c. 1170–80

-

Tomb of Ermengol IX of Urgell (died 1243)

-

Aztec

-

Attributed to Jean de Touyl (French, died 1349), Reliquary Shrine from the convent of the Poor Clares at Buda

-

Attributed to Jean Le Noir, Psalter of Bonne de Luxembourg, 14th cen. illuminated manuscript

-

Andrea da Giona, Altarpiece with Christ in Majesty, c. 1434

-

Schwaben, c. 1489

-

Andre-Charles Boulle(1642–1732) – Commode

-

Interior of the early colonial home ofJohn Wentworth, lieutenant governor of New Hampshire

-

Standing male worshiper, Mesopotamian, 2750–2600 BCE(?)

-

Sphinx, Greece, c. 530 BCE

-

Busto de Anicia Iuliana, Roman

-

Roman, c. 430

-

Book Cover with Byzantine Icon of the Crucifixion, before 1085

-

Cross of San Salvador de Fuentes, late 11th – early 12th century, Asturias, Spain

-

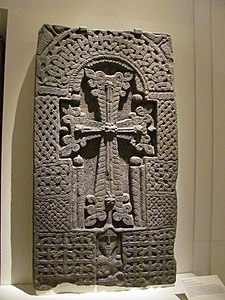

Khatchkar. Basalt

-

Alpan carpet, 1800s

-

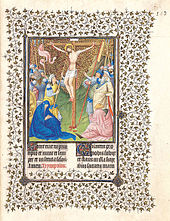

The Crucified Christ, c. 1300, Northern Europe

-

Doorway in granite, in oak, France, Limousin, 15th c., Aixe sur Vienne

-

Aldobrandini Tazza of the Roman emperor Vitellius, c. 1590s

-

Neminatha, Akota Bronzes (7th century CE)

Selected paintings

-

Rogier van der Weyden, Polyptych with the Nativity, c. 1450

-

Caravaggio, The Musicians, 1595

-

The Fortune Teller, c. 1630

-

Rembrandt, Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer, 1653

-

J. M. W. Turner, The Grand Canal, 1835

-

Thomas Cole, The Oxbow, 1836

-

Eugène Delacroix, Christ Asleep during the Tempest, 1853

-

Rosa Bonheur, The Horse Fair, 1853–1855

-

Edgar Degas, The Dancing Class, 1872

-

Boating, 1874

-

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Mme. Charpentier and Her Children, 1878

-

Paul Cézanne, The Card Players, 1890–1892

-

Epte River near Giverny), 1891

-

Paul Gauguin, The Siesta, 1894

-

Winslow Homer, The Gulf Stream, 1899

-

The Houses of Parliament (Effect of Fog), 1903–1904

-

Pablo Picasso, The Oil Mill (Moulin à huile), 1909

-

Wassily Kandinsky, Improvisation 27, Garden of Love II, 1912 (exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show)

-

Arthur Dove, Cow, 1914

-

A Goldsmith in His Shop, Possibly Saint Eligius, 1449

-

El Greco, Opening of the Fifth Seal, 1608–1614

-

Peter Paul Rubens, Rubens, Helena Fourment, and Their Son Frans, ca. 1635

-

Francisco Goya, Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zúñiga, 1777–1778

-

Self-portrait with Straw Hat, 1887

-

Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne (Hortense Fiquet, 1850–1922) in a Red Dress, 1888–90

-

Pablo Picasso, l'Acteur (The Actor), 1904–05

-

Henri Matisse, The Young Sailor II, 1906

-

Georges Braque, Still Life with Mandola and Metronome, late 1909

-

Pablo Picasso, Still Life with a Bottle of Rum, 1911

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ Not to be confused with the Metropolitan Opera in New York City, which is also nicknamed "The Met"

Citations

- ^ a b "Metropolitan Museum Launches New and Expanded Web Site" Archived November 28, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, press release, The Met, January 25, 2000.

- ^ "Today in Met History: April 13". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on January 17, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art | About". www.artinfo.com. 2008. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ a b "Brief History of The Museum". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ New York Times, March 24, 2024

- ^ "New York Times", March 12, 2024, "Audience Snapshot; Four Years After Shutdown, a Mixed Recovery"

- ^ "General Information - The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved March 6, 2024.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Curatorial Departments". Archived from the original on December 1, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- ISBN 0-300-10615-7.

- ISBN 0-300-09876-6.

- ISBN 0-300-10522-3.

- ^ "Departmental Placement Descriptions". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. November 20, 2018. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Ancient Near Eastern Art". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ "Assyria, 1365–609 B.C. | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on July 4, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ JSTOR 3269260.

- ^ a b "How Art Collected by a Long-Lost Rockefeller Changed the Met Museum Forever". Observer. August 26, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- OCLC 4036323.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ISSN 0257-9774.

- ISBN 0-87099-632-0.

- S2CID 155849155.

- ^ Gabriella Angeleti (December 14, 2021). "The Met begins $70m renovation of African, ancient American and Oceanic art galleries". The Art Newspaper.

- ^ "The Met to Return 15 Sculptures to India" (Press release). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. March 30, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ "New York Metropolitan Museum of Art to return 15 smuggled sculptures to India". Mint. April 1, 2023. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Asian Art". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ "Asian Art | the Metropolitan Museum of Art". Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ^ "Meet the Staff | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Egyptian Art". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on June 8, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ISBN 978-0856982071.

- ^ Diana Craig Patch named Curator in charge of Department of Egyptian Art.www.metmuseum.org September 10, 2013

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – European Paintings". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on May 28, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Cordova, Ruben C. (December 14, 2021). "Deaccessioning at the Met: From Scandal to Plein-Air Bonanza to Collection 'Care'". Glasstire.

- ^ "The Met to Reopen 45 Newly Installed European Paintings Galleries on November 20, 2023 – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ Barron, James (November 16, 2023). "679 Paintings. Sculptures. A Sword. The Met Moved Them All". New York Times.

- ^ "Expanded and Renovated Galleries for 19th- and Early 20th-Century European Paintings and Sculpture – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (December 7, 2007). "Age of Splendor Expands". New York Times.

- ^ "The Robert Lehman Collection". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ "b1016713 1". libmma.contentdm.oclc.org. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ "Met Museum". Met Museum. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ a b ""Buying Pictures for New York: The Founding Purchase of 1871": Metropolitan Museum Journal, v. 39 (2004) – MetPublications – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ ISSN 1949-9833.

- ^ doi:10.2307/3257714.

- ^ a b c Cordova, Ruben C. (June 15, 2020). "Oil Begets Oil: Wrightsman Gifts to the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Department of European Paintings". Glasstire.

- ^ a b c "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – European Sculpture and Decorative Arts". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Museum – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ "Splendid Legacy: The Havemeyer Collection – MetPublications – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ "Exhibition The Havemeyer Collection When America Discovered Impressionism... | Musée d'Orsay". www.musee-orsay.fr. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ "The Annenberg Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Masterpieces". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ "The Annenberg Collection: Masterpieces of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism – MetPublications – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ Kimmelman, Michael (June 2, 1991). "From Strength to Strength: A Collector's Gift to the Met". New York Times.

- ^ "Sabine Houdon". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ "The New American Wing". metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013.

- ^ "Dr. Sylvia L. Yount Named to Post at The Met". June 11, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- ^ "Meet the Staff". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- ^ a b "The Metropolitan Museum of Art". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ "'Most of These Items Are Not Art': Native American Advocacy Group Protests Met Show". Frieze. November 7, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Sharp, Kathleen (April 25, 2023). "Is the Metropolitan Museum of Art Displaying Objects That Belong to Native American Tribes?". ProPublica. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ a b Bahr, Sarah (September 9, 2020). "The Met Hires Its First Full-Time Native American Curator". New York Times. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ Attributed to the Bastis Master. "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Greek and Roman Art". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on July 4, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ "What is the Metropolitan Museum of Art?". study.com. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ "Ancient Greek Pottery". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Kimmelman, Michael (April 20, 2007). "Classical Treasures, Bathed in a New Light". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ^ Kennedy, Randy (October 30, 2011). "Interactive Guide to Islamic Art Galleries at Met". The New York Times. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Islamic Art". Metmuseum.org. November 1, 2011. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ Mikdadi, Salwa (2000). "West Asia: Between Tradition and Modernity". New York: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History; The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on December 8, 2011.

- ^ "Placing Islamic Art on a New Pedestal". The New York Times. September 22, 2011. Retrieved June 9, 2023.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art Announces Major Gift from Qatar Museums". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "Qatar Has Given the Metropolitan Museum of Art a 'Generous' Gift to Supercharge Its Islamic Art Department". Artnet News. September 22, 2022. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Flynn, Erica (September 28, 2022). "New partnership between Qatar Museums and New York City art museum strengthens the continued idea of scholarly cooperation". Magzoid. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "Arms and Armor: Notable Acquisitions 2003–2014". Archived from the original on September 28, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 0-8050-1034-3.

- ^ a b c d Bayer, Andrea; Laura D. Corey, eds. (2020). "Making The Met, 1870–2020". www.metmuseum.org. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Arms and Armor". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on May 15, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ "Arms and Armor—Common Misconceptions and Frequently Asked Questions". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art to Receive Major Gift of European Arms and Armor from Ronald S. Lauder – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ "1944". Playbill. Archived from the original on April 8, 2009. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

Philanthropist Irene Lewisohn died today in New York City. She and her sister Alice built and endowed the Neighborhood Playhouse. With Aline Bernstein she founded the Museum of Costume Art on Fifth Avenue in 1937.

- ^ "The Costume Institute | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – The Costume Institute". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on June 21, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ Bourne, Leah (May 5, 2011). "Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Met Gala (But Were Too Afraid To Ask)". NBC New York. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ Trebay, Guy (April 29, 2015). "At the Met, Andrew Bolton Is the Storyteller in Chief". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ Tomkins, Calvin (March 25, 2013). "Anarchy Unleashed". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ Postrel, Virginia (May 2007). "Dress Sense". The Atlantic. p. 133.

- ^ "Liv Tyler and Stella McCartney Reminisce About the Time They Wore Hanes to the Met Gala". Vogue. May 5, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "Extreme Beauty: The Body Transformed". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "Chanel Returning to the Met for Its Pre-Fall Show". WWD. September 4, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "Photos From 'American Woman:Fashioning A National Identity' At The Met". HuffPost. July 28, 2010. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Karimzadeh, Marc (January 14, 2014). "Met Names Costume Institute Complex in Honor of Anna Wintour". Women's Wear Daily. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ Chu, Christie (September 9, 2015). "Andrew Bolton Takes Over Costume Institute". Artnet News. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "History of the Department". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "Gertrude Käsebier | William M. Ivins Jr". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "History of the Department". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Cordova, Ruben (November 28, 2021). "Taking it to the Street: the Guerrilla Girls' Struggle for Diversity". Glasstire.

- ^ "Drawings and Prints". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – The Robert Lehman Collection". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on June 8, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ "The Robert Lehman Collection" (Press release). Metropolitan Museum of Art. September 1999. Archived from the original on February 12, 2006.

- ^ ISBN 978-0671738549.

- ^ "The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings – MetPublications – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ "The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 2, Fifteenth- to Eighteenth-Century European Paintings: France, Central Europe, The Netherlands, Spain, and Great Britain – MetPublications – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ "French Nineteenth-Century Drawings in the Robert Lehman Collection – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ Russell, John (February 18, 2000). "Art Review: Feast of Illuminations and Drawings". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 27, 2008.

- ^ "The Robert Lehman Collection, Volume XV: European and Asian Decorative Arts – MetPublications – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ "The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 10, Italian Majolica – MetPublications – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ "The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 3, Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Paintings – MetPublications – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ Sterling, Charles (1987). The Robert Lehman Collection. p. 6. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- ^ "Medieval Art and The Cloisters". The Met. July 16, 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ "Christmas Tree and Neapolitan Baroque Crèche". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Cloisters Museum and Gardens". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-89424-390-2.

- ISBN 978-1-58839-294-7.

- ISBN 978-1-58839-176-6.

- ISBN 978-1-58839-645-7.

- ^ Hickman, Matt (November 30, 2021). "Metropolitan Museum of Art bestowed with $125 million to renovate its modern art wing". The Architect's Newspaper. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ Tomkins, Calvin (January 18, 2016). "The Met and the Now". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Leonard Lauder Donates $1 Billion Art Collection To Met". British Vogue. April 10, 2013.

- ^ "Acquisitions of the month: August–September 2018". Apollo Magazine. October 3, 2018.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Musical Instruments". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ "Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown's Collection Celebrates 125 Years at the Met". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ R. L. Barclay. "The conservation of musical ins trurnents". unesdoc.unesco.org. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Photographs". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on June 21, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ "The Alfred Stieglitz Collection | About". Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Rosenberg, Karen (September 28, 2007). "Modern Photography in a Brand-New Space". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 23, 2016.

- ^ Behind the Scenes: The Working Side of the Museum, 1928 | From the Vaults, retrieved February 1, 2020

- ^ "Digital Underground". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017.

- ^ Burdette, Kacy (February 7, 2017). "The Met Makes 375,000 Public Domain Images Available". Fortune.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ Gabriella Angeleti (May 24, 2022). "The Met creates digital project tied to $70m upgrade of African, ancient American and Oceanic art galleries". The Art Newspaper.

- ^ The Met. "Open Access at The Met". The MET. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ "The Met Libraries". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on May 27, 2013.

- ^ "Collections". Archived from the original on December 19, 2014.

- ^ "Access Hours and Policies". Archived from the original on May 15, 2014.

- ^ "Libraries and Study Centers". Archived from the original on September 8, 2013.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Exhibitions". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on September 23, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- doi:10.1353/ams.0.0137. Archived from the originalon October 18, 2014.

- ^ Michael Rosenfeld Gallery. "Norman Lewis – First Major African American Abstract Expressionist". Violette de Mazia Foundation. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "In America: An Anthology of Fashion".

- ^ "Everything You Need to Know About the 2022 Met Gala". Vogue. March 29, 2022.

- ^ Disturnell, John New York as it was and as it is Archived January 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, D. Van Nostrand, New York, 1876. "Metropolitan Museum of Art", p. 101.

- ^ from the original on May 6, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives: Henry Gurdon Marquand Papers" (PDF). September 11, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Moske, James. "This Weekend in Met History: February 20". Museum Archives. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ "Eastman Johnson – Co-founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art". Archived from the original on April 13, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0521385404.

- ^ "The Lost Harriet Douglas Cruger Mansion – No. 128 West 14th Street," Daytonian in Manhattan, 8/24/2015". August 24, 2015..

- ^ ISBN 978-0767924887.

- ^ Finding aid for Schools of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Records (1879–1895) Archived April 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved July 31, 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-08-046475-6.

- ^ Danziger (2007), p. 135

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art Announces 2004–2005 Season of Concerts, the 51st Season" Archived August 13, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004; and "Metropolitan Museum Announces Departure of Concerts & Lectures General Manager Hilde Limondjian" Archived February 10, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Metropolitan Museum of Art, May 26, 2010

- ^ Lamont, Lansing. "Tom Hoving and the Met Builds", People magazine, November 17, 1975. "Tom Hoving of the Met Builds, Buys and Makes Much of the Art World Bilious". Archived from the original on February 10, 2018. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ "The Robert Lehman Collection". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. September 1999. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ George Trescher records related to The Metropolitan Museum of Art Centennial, 1949, 1960–1971 (bulk 1967–1970) Archived August 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ^ Pillifant, Reid (May 19, 2009). "Michael Gross Gets Lots of Dirty Looks But Little Buzz for Rogues' Gallery". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on March 30, 2015. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ Holterhoff, Manuela (May 14, 2009). "Secrets, Phonies Animate Lively Met Museum History: Interview". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on October 19, 2008.

- ^ Finnerty, Amy (June 28, 2009). "Exhibitionists". The New York Times Book Review. Archived from the original on July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b "Met Museum Changes Leadership Structure". NY Times. June 13, 2017. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ "A Look at the Met Breuer Before the Doors Open" Archived April 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine by Randy Kennedy, The New York Times, March 1, 2016

- ^ The Met Breuer Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, he Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Frick Collection Planning Collaboration to Enable Frick to Use Whitney Museum of American Art's Breuer Building During Frick's Upgrade and Renovation" (PDF). www.frick.org (Press release). September 21, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ "The Met Is Looking to Leave the Breuer Building After Just Two Years". Architectural Digest. September 26, 2018. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ New York Times. Archivedfrom the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ^ Weaver, Shaye (June 24, 2020). "The Metropolitan Museum of Art has an official reopening date". Time Out. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ "Patricia Marroquin Norby Named Associate Curator of Native American Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. September 8, 2020. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "Met Announces Patricia Marroquin Norby as First Full-Time Curator of Native American Art". www.artforum.com. September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Yount, Sylvia; Norby, Patricia Marroquin (May 12, 2021). "This Is Lenapehoking". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "The Met Announces Architect for Oscar L. Tang and H.M. Agnes Hsu-Tang Wing". March 14, 2022.

- ^ Schrader, Adam (March 27, 2024). "Museums Struggle to Respond as Pressure Mounts to Take Stand on Gaza". Artnet News. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ Pontone, Maya (March 11, 2024). "Met Museum Staff Urges Leaders to Address Israel's Attacks on Gaza". Hyperallergic. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ Halford, Macy (December 1, 2008). "At the Museums: Four Eyes". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008.

- ^ Gross, Michael, Rogues' Gallery, The Secret History of the Moguls and the Money That Made the Metropolitan Museum, Broadway Books, New York, 2009, p. 75.

- ^ The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (Summer 1995)

- ^ Ethridge, Alexandria (December 28, 2016). "How Did You Build This Museum? And More #MetKids Questions!". The Met. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art at HumanitiesWeb". Humanitiesweb.org. January 13, 2012. Archived from the original on June 1, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (May 4, 2009). "The Met Offers a New Look at Americana". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 26, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- ^ Heckscher, Morrison H. (Summer 1995). "The Metropolitan Museum of Art: An Architectural History" (PDF). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 54. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-885492-31-9.

- ISBN 978-1-57912-801-2.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 9, 1967. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 19, 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ "NHL nomination for Metropolitan Museum of Art". National Park Service. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ Kennedy, Randy (March 10, 2015). "Metropolitan Museum of Art Names New President: Daniel Weiss". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ^ Greenberger, Alex (April 10, 2018). "Metropolitan Museum of Art Names Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco's Max Hollein Director". ARTNews. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (August 3, 2022). "Max Hollein Consolidates Roles as Met Museum's Chief". The New York Times. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum board appoints first woman co-chair". November 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Annual Report: Board of Trustees" (PDF). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. November 1, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 17, 2014.

- ^ "'The ultimate status symbol': Adams appoints nightclub owner to Metropolitan Museum board". Politico. May 5, 2022. Retrieved June 9, 2023.