Paramount Theatre (Atlanta)

| Paramount Theatre | |

|---|---|

US$1,000,000 | |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Philip T. Shutze |

| Architecture firm | Hentz, Reid & Adler |

| Other information | |

| Seating capacity | 2,700 |

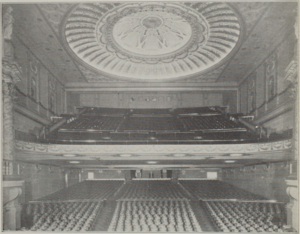

The Paramount Theatre was a movie palace in downtown Atlanta, Georgia, United States. The building was designed by Philip T. Shutze and was completed in 1920 as the Howard Theatre, a name it kept until 1929. It was located at 169 Peachtree Street, in an area that soon became the location of several other major theaters, earning it the nickname "Broadway of the South". With a seating capacity of 2,700, it was at the time the second largest movie theater in the world, behind only the Capitol Theatre in New York City. In addition to functioning as a movie theater, the building hosted live performances, with several nationally renowned orchestras playing at the venue through the 1940s and Elvis Presley playing at the theater in 1956. By the 1950s, however, movie palaces faced increased competition from smaller movie theaters and the rise in popularity of television, and the Paramount was demolished in 1960.

History

Background and construction

The 1 acre (0.40 ha) of land in downtown Atlanta on which the theater would eventually be built traded hands several times throughout the late 1800s before it was sold to Asa Griggs Candler for $97,000 on November 30, 1909.[2] Candler sold the land on April 17, 1911, to brothers Forrest and George W. Adair Jr. for $120,000.[2] On March 28, 1919,[3] the Adairs agreed to lease the land to C. B. and George Troup Howard,[2] the latter of whom was a successful cotton merchant.[4] The lease was granted on the condition that a theater be built on the property, which at this time had a valuation of $625,000.[2] The theater's value, including its equipment, was to be greater than $250,000.[3] At the end of the 25-year lease, the property, including the theater, would revert to the Adairs.[3] Prior to the theater's construction, several one-story commercial stores were located on the property.[5]

The design of this new building, to be called the Howard Theatre, was handled by the Atlanta-based

Theater in operation

Upon its opening, the theater was well received by the general public. Contemporary publications in the city called it one of the "show spots of the city"

As a performing arts venue, the theater hosted the

Architecture

The theater building had dimensions of 90 feet (27 m) by 275 feet (84 m).

The interior of the theater was designed in the

Notes

- Atlanta Historical Society's official publication have differed, with either Neel Reid or Shutze (both architects for Hentz, Reid & Adler) cited as the building's architect.[8][7] In a 1986 article on Shutze, historian Elizabeth Meredith Dowling states that the Italian-inspired architecture of the building points to Shutze as the designer, as he had recently spent time studying architecture in Rome before returning to work in Atlanta.[7] Additionally, a letter written during the time of the theater's construction from Allyn Cox to his mother makes mention of Shutze's work on a theater design that is most likely in reference to the Howard Theatre.[7] Furthermore, a 2017 article published in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution states that Shutze was the architect for the theater.[9]

References

- ^ The City Builder 1933, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f g Garrett 1969a, pp. 350–351.

- ^ a b c The City Builder 1921c, p. 18.

- ^ a b Garrett 1969b, p. 778.

- ^ a b Chapman 1932, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e f Craig 1995, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dowling 1986, p. 43.

- ^ McCall 1973, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Johnston 2017.

- ^ a b Trotti 1924, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e The City Builder 1921a, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Jones 1923, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l The City Builder 1920, p. 20.

- ^ Trotti 1931, p. 4.

- ^ Spain 1923, p. 10.

- ^ Sherry 1977, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Trotti 1924, p. 13.

- ^ Spain 1923, p. 11.

- ^ The City Builder 1921b, p. 16.

- ^ The City Builder 1923, p. 7.

- ^ Barker 1930, p. 24.

- ^ McKinley 1990–1991, p. 18.

- ^ Martin 1987, p. 7.

- ^ Johnston 2016.

Sources

- Barker, B. S. (May 1930). "What the Chamber of Commerce is Doing". The City Builder. Atlanta Chamber of Commerce: 24–27.

- Chapman, Ashton (November 1932). "Past Ten Years Were Atlanta's Greatest". The City Builder. Atlanta Chamber of Commerce: 17–18.

- "Two New Theatres for Atlanta". The City Builder. V (6). Atlanta Chamber of Commerce: 20. August 1920.

- "Howard Theatre Pleases Atlanta". The City Builder. V (12). Atlanta Chamber of Commerce: 17. February 1921.

- "Miss Young Entertained". The City Builder. VI (2). Atlanta Chamber of Commerce: 16. April 1921.

- "Howard Theatre Property". The City Builder. VI (5 & 6). Atlanta Chamber of Commerce: 18. July–August 1921.

- "Atlanta Pays Tribute to Harding". The City Builder. VIII (6). Atlanta Chamber of Commerce: 7. August 1923.

- "New Chamber of Commerce Members for September". The City Builder. XVII (5). Atlanta Chamber of Commerce: 13. October 10, 1933.

- Craig, Robert M. (1995). Atlanta Architecture: Art Deco to Modern Classic, 1929–1959. Foreword by ISBN 978-1-4556-0044-1.

- Dowling, Elizabeth Meredith (Summer 1986). "Philip Trammell Shutze: A Study of the Influence of Academic Discipline on His Early Residential Design". Atlanta Historical Society: 33–54.

- ISBN 978-0-8203-3903-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8203-3904-7.

- Johnston, Andy (August 15, 2016). "Which four Atlanta venues did Elvis play before his death?". from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- Johnston, Andy (January 2, 2017). "Paramount had 40-year run on Peachtree". from the original on January 3, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- Jones, Raymond B. (October–November 1923). "What to See in Atlanta and Where to See It". The City Builder. VIII (8 & 9). Atlanta Chamber of Commerce: 26–27.

- Martin, Harold H. (1987). Atlanta and Environs: A Chronicle of Its People and Events, 1940s-1970s. Vol. III (1st ed.). Athens, Georgia: ISBN 978-0-8203-3907-8.

- McCall, John Clark Jr. (Spring–Summer 1973). "The Roxy Theatre: Recollections of Vaudeville in Atlanta". Atlanta Historical Society: 21–26.

- McKinley, Edward H. (Winter 1990–1991). "Brass Bands and God's Work: One Hundred Years of the Salvation Army in Georgia and Atlanta". Atlanta Historical Society: 5–37.

- Sherry, Grace T. (Summer 1977). "Editorial". Atlanta Historical Society: 7–9.

- Spain, Helen Knox (October–November 1923). "Atlanta Symphony Orchestra". The City Builder. VIII (8 & 9). Atlanta Chamber of Commerce: 10–11.

- Trotti, Lamar (November 1924). "The Marvelous Product of Twenty Years". The City Builder. Atlanta Chamber of Commerce: 11–15.

- Trotti, Lamar (February 1931). "Atlanta's "Film Row" Handles 1,600 Miles a Day". The City Builder. Atlanta Chamber of Commerce: 3–4, 39.