Percy Molteno

Percy Molteno | |

|---|---|

Philanthropist | |

Percy Alport Molteno (12 September 1861 – 19 September 1937) was an Edinburgh-born South African lawyer, company director, politician and philanthropist who was a British Liberal Member of Parliament (MP) from 1906 to 1918.[2][3]

Early life

Molteno was born in Edinburgh, the second son of

Shipping magnate

After qualifying as a barrister, and practising law in the Cape for several years, he moved to Britain to accept a partnership in the firm of Donald Currie & Company, managers of the Castle (later, the Union-Castle) Line and even married Sir Donald Currie's daughter Elizabeth.

As chairman of the Union Castle Company he oversaw a massive expansion in export shipping lines from Southern Africa, eventually, through these shipping lines, controlling the routes of the bulk of southern Africa's foreign trade.[5]

From the beginning, he saw great potential in South Africa's agricultural exports. His father had undertaken the first experimental export of fruit as a young man in 1841, loading a ship with dried fruit for the Australian market. Percy however, was keenly interested in the possibility of using the new science of refrigeration to allow South African produce to be successfully shipped to the enormous European consumer markets, thereby opening them up for South African exports.

Having a scientific frame of mind, he embarked on an extensive process of research and experiments in refrigeration techniques for large shipping vessels. The result was that he developed and brought in new refrigeration methods to allow for the first successful introduction of South African fruit to European and other overseas markets. On 31 January 1892, when the first shipment arrived in Britain, John X. Merriman from the Cape Government accompanied him to see the cases opened, and when case after case opened in perfect condition, the relief and joy was immense. Land prices in the Cape immediately shot up, and a new economic chapter was opened for Southern Africa.[6]

At the same time, he established Southern Africa's first fruit export organisation, with an eye to developing and controlling the Cape's agricultural exports. Although this was originally set up as a

He is consequently regarded as the pioneer of the South African export fruit industry.[2][10][11]

Political career

Molteno was elected in 1906 as a Liberal Member of the UK Parliament (MP) for Dumfriesshire, where he came to represent a radical wing of the British Liberal Party.

He had originally needed to move to London to oversee his vast network of international shipping lines, but he remained deeply attached to southern Africa. His close friend the activist John Tengo Jabavu called him "a true son of the soil, and a South African patriot I know and admire".[12] He also remained closely involved in its politics, through his many influential family members, as well as through his friendship with nearly all of the most powerful South African politicians and businessmen.

He was a prolific letter-writer who corresponded with many of the leading political figures of the colony. His writings and politics were guided by two main themes: his advocacy of

Opposition to the Boer War

In the early 1890s, the rise of pro-imperialist politicians such as

From very early on, Molteno foresaw the nature of the upcoming conflict and, through his correspondence with the leading politicians of the day, sought to warn them, and attack "official ignorance in high places of the realities in South Africa".

Finally, when war broke out, he took his place in the heart of British society as openly "Pro-Boer".[2][15]

Not surprisingly the effects of such political activism on his business empire were devastating.

In 1896, after the

- "What a blow to all our hopes of friendly feeling and consolidation of races has been given by the wicked attempt of foolish men, elated by the enormous gains which Africa has yielded to them - what a miserable return to have made to her for such benefits!"[2]

Postwar reconstruction

In the years following the Boer War, Molteno withdrew from the shipping trade and devoted both himself and his remaining fortune to postwar humanitarian efforts in South Africa.

Having returned to South Africa to see what he could do to "salvage something from the wreckage"

Movement towards union

Molteno entered the British

He was deeply involved in the process leading up to the Union of South Africa in 1910. He was also the adviser and confidant of a number of leading South African statesmen during this process.[18]

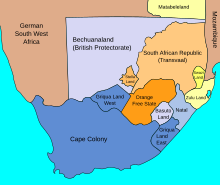

Molteno saw the upcoming union as politically inevitable and not necessarily a bad thing. He had, after all, been advocating the ending of animosities between

Molteno had been acutely aware of the earliest beginnings of that tendency many years earlier, and it increasingly became his primary concern about the political future of South Africa. It also led him to intensify his support for the cause of black African nationalist movements, and activists such as John Tengo Jabavu. Jabavu was a political ally and old friend of his brothers, the Cape

Molteno supported the extension of the Cape's multiracial "

Thus, supporters of universal franchise, led by

A final compromise saved a weak form of qualified franchise but only in the liberal Cape. Molteno, who increasingly saw even the qualified franchise as insufficiently inclusive, called the compromise "pathetic" and predicted a worsening struggle over the issue of political rights. His later letters to Botha and Merriman (1914) warn of history repeating itself in "poor South Africa" and of approaching troubles to which he could see no end.[24]

Later life and humanitarian work

Developments after the Union like the rise of Afrikaner nationalism and apartheid led to his disillusionment with South African politics and his increasing devotion to humanitarian issues such as the Vienna Emergency Relief Fund, which he started in 1919.

In South Africa, he publicly supported and donated large sums of money to the fundraising activities of

Molteno was a rationalist and a great supporter of scientific endeavour (The

He was also a fellow of the

In person, family friend Frederick Selous described him "acutely intelligent" and unusually open-minded.[27]

A very unostentatious man who despised flatterers and time-servers, he throughout his life repeatedly refused titles and honours, though his influence behind the scenes was immense. Famously, when Prime Minister Botha initially refused to attend the 1907 Imperial Conference to discuss Union, it was a personal and undisclosed cable from Molteno that brought Botha to London in a cooperative frame of mind.[2]

Molteno's family was originally Italian and, throughout his life, he visited Italy for extended periods. He was, particularly, attached to the island of

References

- ISSN 1479-9642.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Vivian Solomon, ed. (24 July 1981). "Selections from the correspondence of Percy Alport Molteno 1892-1914". Historical Publications South Africa. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019.

- ^ ISBN 0-900178-27-2.

- ^ "Molteno, Percy Alport (MLTN881PA)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ H.H. Hewison: Hedge of Wild Almonds: South Africa, the Pro-Boers & the Quaker Conscience, 1890-1910. James Currey Publishers:London, 1989.

- ^ De Beer, G. 160 Years of Export. Cape Town: PPECB, 2003. p.21-27.

- ^ Murray, M: Union-Castle Chronicle: 1853-1953. Longmans Green, 1953. p.314

- ISBN 1-874950-45-8

- ^ De Beer, G. 160 Years of Export. Cape Town: PPECB, 2003. p.14.

- ^ Fruit and Food Technology Research Institute, Stellenbosch: Information Bulletin no.22.(1971)

- ^ "The Deciduous fruit industry in South Africa - MyFundi". Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ Phyllis Lewsen (ed.). Selections from the correspondence of John X. Merriman, 1905-1924. South Africa: Van Riebeeck Society, 1969. p.132.

- Lunn, Henry (1918). Chapters from my Life. London: Gassell and Company. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ^ The South Africa Conciliaton Committee, list of names and addresses (1899). National Press Agency, London. SACC. 1899.

- ISBN 0-624-01200-X.

- ^ Letter from Catherine Courtney to Molteno, 23.8.1902

- ^ http://www.liberalhistory.org.uk/uploads/47-Summer%25202005.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ Phyllis Lewsen (ed.). Selections from the correspondence of John X. Merriman, 1905-1924. South Africa: Van Riebeeck Society, 1969. p.164.

- ^ L.D. Ngcongco: Jabavu and the Anglo-Boer War. South Africa: Kleio, 1970.

- ^ D.D.T. Jabavu: The Life of John Tengo Jabavu. South Africa: Lovedale. 1922

- ^ L.M. Thompson: The Unification of South Africa, 1902-1910. Oxford, 1960.

- ^ M.A. Grundlingh: The Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope, 1872-1910. Archives Year Book for South African History, 1969, Vol II.

- ^ Phyllis Lewsen: Merriman as last Cape Prime Minister. The South African Historical Journal. Nov 1975.

- ^ P.A. Molteno (1914): Letter dated 13 February 1914. Edited by J.W.E. van de Poel. South African Library: The Merriman Papers.

- ^ Heather Hughes: The First President: A Life of John L. Dube, Founding President of the ANC. Jacana Media, 2011. p.153.

- ^ Brian Willan: Sol Plaatje, South African nationalist, 1876-1932. Heinemann, 1984. p.186.

- ^ Mrs F.C. Selous (25 September 1937). "A True Son of South Africa". South Africa. Cape Town.

Further reading

- Vivian Solomon: Selections from the correspondence of Percy Alport Molteno 1892-1914. Van Riebeeck Society, 1981. ISBN 0-620-05662-2

- P.A. Molteno: The Export of Cape Fruit. N.p. London. 1892.

- P.A. Molteno: A Federal South Africa. Sampson Low, Marston & Co, 1896. ISBN 1-4367-2682-4

- P.A. Molteno: The South African Crisis: A Plain Statement of Facts. S.A.C.C. Publications, 1899.

- Molteno, Percy Alport (1900). The Life and Times of Sir John Charles Molteno, K.C.M.G., First Premier of Cape Colony: Comprising a History of Representative Institutions and Responsible Government at the Cape and of Lord Carnarvon's Confederation Policy & of Sir Bartle Frere's... London: Smith, Elder & Co. ISBN 978-1-277-74131-5.

- P.A. Molteno: A plea for Small-holdings. The Liberal Publication Department, 1907.

- P.A. Molteno: The Proposed Guarantee Pact. R. Cobden-Sanderson, 1925.

- P.B. Simons: Apples of the sun : being an account of the lives, vision and achievements of the Molteno brothers. Vlaeberg: Fernwood Press, 1999. ISBN 1-874950-45-8

External links

- Works by or about Percy Molteno at Internet Archive

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Percy Molteno