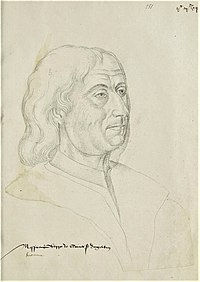

Philippe de Commines

Philippe de Commynes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1447 |

| Died | c. 1511 Argenton-les-Vallées, Poitou |

| Occupation(s) | writer, diplomat, politician |

Philippe de Commines (or de Commynes or "Philippe de Comines";

Biography

Early life

Commines was born at

Burgundy

In 1468, he became a knight in the household of

In 1470 Commines was sent on an embassy to

Commines was a great favorite with Duke Charles for seven years (going back to when he had still been Count of

"When we are versed in the history of the times, we often discover that memoir-writers have some secret poison in their hearts. Many, like Comines, have had the boot dashed on their nose. Personal rancour wonderfully enlivens the style... Memoirs are often dictated by its fiercest spirit; and then histories are composed from memoirs. Where is TRUTH? Not always in histories and memoirs!"

Service of Louis XI

D'Israeli says Commines so resented his nickname that it was the reason he suddenly left Burgundy and went into the service of the French king, but the financial incentives offered by Louis provide a more than adequate explanation: Commines was still heavily burdened with his father's debts. He fled by night from Normandy on 7 August 1472, and joined Louis near Angers. On the following morning, when Duke Charles discovered his servant and god-brother missing, he confiscated all of Commines' property. These were later given to Philip I of Croÿ-Chimay.

As a long-time enemy of

When Louis began to suffer ill-health, Commines was apparently welcomed back into the fold and performed personal services for the king. Many of his activities during the period seem to have involved a degree of secrecy; he was effectively acting as a kind of undercover agent. However, he never regained the level of intimacy with the king that he had previously enjoyed, and Louis's death in 1483, when Commines was still only in his thirties, left him without many friends at court. Nevertheless, he retained a place on the royal council until 1485. Then, having been implicated in the Orleanist rebellion, he was taken prisoner and kept in confinement for over two years, from January 1487 until March 1489. For some of that period, he was kept in an iron cage.

Mémoires

After his release, Commines was exiled to his estate at Dreux, where he began to write his Mémoires. (This title was not used until an edition of 1552.) By 1490, however, he was recovering his position at court and was in the service of King Charles VIII of France. Charles never allowed him the privileged position he had held under Louis, and he was once again used as an envoy to the Italian states. However, his personal affairs were still problematic, and his right to some of the possessions given him by Louis was subject to legal challenges.

In 1498 (fifteen years after the death of

The Mémoires are divided into "books", the first six of which were written between 1488 and 1494, and relate the course of events from the beginning of Commines' career (1464) up to the death of King Louis. The remaining two books were written between 1497 and 1501 (printed in 1528), and deal with the Italian wars, ending in the death of King Charles VIII of France.

Commines' scepticism is summed up in his own words: Car ceux qui gagnent en ont toujours l'honneur ("For the honours always go to the winners"). Some have disputed whether his candid phrases disguise a deeper dishonesty. Yet at no time does he attempt to present himself as a hero, even when recounting his military career. His attitude to politics is one of pragmatism, and his ideas are practical and progressive. His reflections on the events he has witnessed are profound by comparison with those of Froissart, who lived a century earlier. His psychological insights into the behaviour of kings are ahead of their time, reminiscent in some ways of the contemporaneous writings of Niccolò Machiavelli. Like Machiavelli, Commines aims to instruct the reader in statecraft, though from a slightly different viewpoint. In particular, he notes how Louis repeatedly got the better of the English, not by military might, but by political machination.

Notes

- ^ Bémont, Charles (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). p. 774.

- ^ a b c Louis René Bréhier (1908). "Philippe de Commines". In Catholic Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Mémoires de Philippe de Commynes. T. 1 (in French). Paris (published 1901). 1489–1498. pp. 193–221. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Mémoires de Philippe de Commynes. T. 2 (in French). 1489–1498. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "Seigneurs d'Amboise" (PDF). Racines et histoire. Etienne Pattou. 26 February 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

References

- Philippe de Commynes: The Reign of Louis XI 1461–83, translated with an introduction by Michael Jones [1]

- Lawton, H.W. (1957). "The Arts in Western Europe: Vernacular Literature in Western Europe". In G. R. Potter (ed.). The New Cambridge Modern History: I. The Renaissance 1493–1520. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 184–185.

- Philippe de Commynes, Mémoires, ed. J. Blanchard, Geneve, Droz, 2007, 2 vol.

- Philippe de Commynes, Lettres, ed. J. Blanchard, Geneve, Droz, 2001

- Joël Blanchard, Philippe de Commynes, Paris, Fayard, 2006

- Cristian Bratu, « Je, auteur de ce livre »: L'affirmation de soi chez les historiens, de l'Antiquité à la fin du Moyen Âge. Later Medieval Europe Series (vol. 20). Leiden: Brill, 2019 (ISBN 978-90-04-39807-8).

- Cristian Bratu, "Je, aucteur de ce livre: Authorial Persona and Authority in French Medieval Histories and Chronicles." In Authorities in the Middle Ages. Influence, Legitimacy and Power in Medieval Society. Sini Kangas, Mia Korpiola, and Tuija Ainonen, eds. (Berlin/New York: De Gruyter, 2013): 183–204.

- Cristian Bratu, "Clerc, Chevalier, Aucteur: The Authorial Personae of French Medieval Historians from the 12th to the 15th centuries." In Authority and Gender in Medieval and Renaissance Chronicles. Juliana Dresvina and Nicholas Sparks, eds. (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012): 231–259.

- Cristian Bratu, "De la grande Histoire à l'histoire personnelle: l'émergence de l'écriture autobiographique chez les historiens français du Moyen Age (XIIIe-XVe siècles)." Mediävistik 25 (2012): 85–117.

External links

- Biography of Philippe de Commines at the New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia

- Bibliography of Philippe de Commines's works, in French

- Works by Philippe de Commines at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)