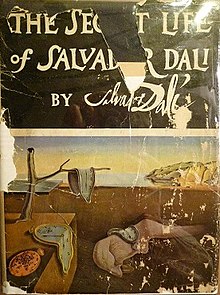

The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí

First edition | |

| Author | Salvador Dalí |

|---|---|

| Original title | La vie secrète de Salvador Dali |

| Illustrator | William R. Meinhardt |

| Cover artist | Salvador Dali, The Persistence of Memory - 1931 |

| Subject | Autobiography |

| Publisher | Dial Press |

Publication date | 1942 |

The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí is an autobiography by the internationally renowned artist

Contents

Dalí opens the book with the statement: "At the age of six I wanted to be a cook. At seven I wanted to be Napoleon. And my ambition has been growing steadily since."

Behind the partly open kitchen door I would hear the scurrying of those bestial women with red hands; I would catch glimpses of their heavy rumps and their hair straggling like manes; and out of the heat and confusion that rose from the conglomeration of sweaty women, scattered grapes, boiling oil, fur plucked from rabbits' armpits, scissors spattered with mayonnaise, kidneys, and the warble of canaries—out of that whole conglomeration the imponderable and inaugural fragrance of the forthcoming meal was wafted to me, mingled with a kind of acrid horse smell.[2]

Dalí states in the book:

- At the age of five years, he encountered an almost dead ants and then put it in his mouth, bit it, and then tore the bat almost in half.[2]

- As a young child, he wore a king's tucked his genitals inside the outfit to look more feminine.[2]

- He stood out dramatically from the poor children in his school by carrying a flexible bamboo cane adorned with a silver dog's head figure and a sailor suit with gold insignia.[2]

- Due to a "refined

- He became interested in necrophilia, but was then later cured of it.[1]

- While walking down the Boulevard Edgar-Quinet in Paris in 1934, he became so disgusted at the sight of a blind double-amputee that he kicked him.[2]

Reception

Essayist, journalist, and author

In July 1999, an article by Charles Stuckey in Art in America stated that Dalí's book "arguably revolutionized a literary genre". He argued that Dalí's book had been intended as slapstick humor and has been generally misinterpreted by critics. He also wrote:

Indebted to the fanciful childhood-oriented writings by artists such as

Influences

American writer and humorist James Thurber wrote a semi-autobiographic article for The New Yorker called The Secret Life of James Thurber on February 27, 1943. In the article, Thurber referred to Dalí's title and parts of his style in comparison to his own life. In particular, Thurber noted with dismay that his own autobiographical book, My Life and Hard Times, sold for only $1.75 a copy in 1933 while Dalí's book sold for a full $6.00 in 1942.[7][8]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dali. George Orwell Online Library. First published: The Saturday Book for 1944. — GB, London. — 1944. Copy retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ Time. December 28, 1942. Archived from the originalon October 14, 2010. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ a b Stuckey, Charles (July 1999). "The Shameful Life of Salvador Dali – Review". Art in America. Retrieved October 11, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Jim Lindgren (September 28, 2009). "Roman Polanski, George Orwell, and Salvador Dali". The Volokh Conspiracy. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

The first writer I encountered who explored this issue was George Orwell in his essay on Dalí. The essay is also memorable because its second sentence contains one of Orwell's most resonant ideas

- ^ a b Jonathan Jones. "Why George Orwell was right about Salvador Dalí". The Guardian. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

George Orwell isn't usually thought of as an art critic... But his contribution to the literature of modern art is also worth celebrating. In 1944 Orwell wrote an essay called Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dalí.

- ISBN 978-0-486-27454-6.

- ^ JAMES THURBER AND THE GREAT DEPRESSION Archived April 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ James Thurber. “The Secret Life of James Thurber”. The New Yorker, February 27, 1943, p. 15