User:Palm dogg/Great Locomotive Chase

Great Locomotive Chase

Background

During the

Their mission was to hold the city at all costs but Mitchel was tempted to sever the

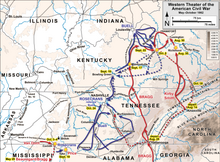

At the time, the standard means of capturing a city was by encirclement to cut it off from supplies and reinforcements, then would follow artillery bombardment and direct assault by massed infantry. However, Chattanooga's natural water and mountain barriers to its east and south made this nearly impossible with the forces that Mitchel had available. When the Union Army threatened Chattanooga, the Confederate States Army would (from its naturally protected rear) first reinforce Chattanooga's garrison from Atlanta. When sufficient forces had been deployed to Chattanooga to stabilize the situation and hold the line, the Confederates would then launch a counterattack from Chattanooga with the advantage of a local superiority of men and materiel. It was this process that the Andrews raid sought to disrupt. If he could somehow block railroad reinforcement of the city from Atlanta to the southeast, Mitchel could take Chattanooga. The Union Army would then have rail reinforcement and supply lines to its rear, leading west to the Union-held stronghold and supply depot of Nashville, Tennessee.

Planning the Second Raid, 6-7 April

James Andrews returned to federal lines, now near Shelbyville, on April 6.

Prelude, 7-11 April

Mitchell takes Huntsville

On the morning of April 11, 1862, Union troops led by General Ormsby M. Mitchel seized Huntsville in order to sever the Confederacy's rail communications and gain access to the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. Huntsville was the control point for the Western Division of the Memphis & Charleston,[2] and by controlling this railroad the Union had struck a major blow to the Confederacy.

The Chase, 12 April

Marietta to Big Shanty

Big Shanty to Kingston

Kingston to Calhoun

Calhoun to Ringgold

Aftermath

Military Situation, April-August

Following the raid, General Mitchell continued to occupy Huntsville until early June. Then General Buell was sent east from Corinth, following the end of the siege to link up with Mitchell. eastward through northern Alabama along the Memphis & Charleston Railroad

Buell moved his column—three divisions totaling 35,000 men— east to Huntsville, poised to join up with Mitchel’s 10,000-man division near Bridgeport, along with Morgan’s 9,000 at Cumberland Gap. The Army of the Ohio was on the move and would soon be united.

As a result, the initial march to Huntsville was followed by a month of idleness and fretting as Buell wrestled with difficulties

In early August, Twelve days later, with Buell still immobile, a substantial Confederate column under the command of General Braxton Bragg was reported crossing the river in force at Chattanooga. In what would come to be recognized as the largest Confederate railroad movement of the war, Bragg had moved his 30,000-man force via a 776-mile circuitous route from central Mississippi through Mobile and Atlanta before appearing in Chattanooga. Buell’s predictable reaction to the news of this threat was initially to pull back northwest up the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad to Decherd, Tennessee, and four days later to order an all-out withdrawal. His entire army, Mitchel’s men included, retreated back to Nashville, firing the newly rebuilt railroad bridges in their wake. By mid-September he was all the way up in Bowling Green, Kentucky, 150 crowflight miles from Chattanooga and 250 from Atlanta. Thanks to a forward push by the harsh, irascible Bragg—whose Rebel force was about half the size of Buell’s reinforced army—and to an appalling lack of nerve by Buell himself, the Confederates had driven the Union army from its hard-won positions in North Alabama and East Tennessee without firing a shot.15

On 29 May, Mitchel dispatched Brigadier General James S. Negley to seize Chattanooga. Negley advanced to the outskirts of the city and conducted a two-day artillery bombardment.[3]

On 29 May, Mitchel sent a small expeditionary force under Brig. Gen. James S. Negley to capture Chattanooga. When Negley reached his objective on 7 June, he conducted a reconnaissance and discovered that the Confederate defenses were too strong to carry by direct assault, so he brought up

While Mitchell's forces skirmished near Chattanooga, Braxton Bragg spent most of June redeploying his 30,000-man army from Tupelo, Mississippi to Chattanooga.[4]

When Bragg pushed north from Chattanooga to Kentucky in mid-August, Buell abandoned Alabama and central Tennessee, [5]

Bowery Jr, Charles R. (2014). The Civil War in the Western Theater 1862 (PDF).

Prokopowicz, Gerald J. (2014). "Last Chance for a Short War: The Chattanooga Campaign of 1862". In Jones, Evan C. (ed.). Gateway to the Confederacy: New Perspectives on the Chickamauga and Chattanooga Campaigns, 1862–1863. Louisiana State University Press.

Capture, 12-21 April

Trials and Executions, April-June

Escape and Exchange, June 1862-March 1863

Location

Outside of Metropolitan Atlanta

The Ohio monument dedicated to the Andrews Raiders is located at the Chattanooga National Cemetery. There is a scale model of the General on top of the monument, and a brief history of the Great Locomotive Chase.

One marker indicates where the chase began, near the Big Shanty Museum (now known as Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History) in Kennesaw, while another shows where the chase ended at Milepost 116.3, north of Ringgold — not far from the recently restored depot at Milepost 114.5.

- Big Shanty Village Historic District

- Camp McDonald

- Acworth Downtown Historic District

- Tarleton Moore House

- Grand Theater (Cartersville, Georgia)

- Old Bartow County Courthouse, now the Bartow History Museum, built so close to the railroad that court was interrupted when any train passed, not built until 1869

- Adairsville Historic District

- the Calhoun Depot, built in 1852-53, at Calhoun, 10 miles north of Adairsville.[6]

- Calhoun Downtown Historic District

- William Taylor House (Resaca, Georgia), associated with northern Georgia soldiers who fought for the Union in the Civil War, though house not built until 1913

- Masonic Lodge No. 238, not built until 1915

- Dalton Commercial Historic District

- Crown Mill Historic District

- Western and Atlantic Railroad Tunnel at Tunnel Hill

- Ringgold Gap Battlefield, gap between White Oak Mountain and Taylor Ridge through which railway runs, site of November 1863 battle protecting Confederate retreat after Battle of Missionary Ridge at Chattanooga

- Ringgold Depot

- Ringgold Commercial Historic District

- marker at milepost 116.3

In Metropolitan Atlanta

The General is now in the Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History, Kennesaw, Georgia, while the Texas is on display at the Atlanta History Center.

One marker indicates where the chase began, near the Big Shanty Museum (now known as Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History) in Kennesaw, while another shows where the chase ended at Milepost 116.3, north of Ringgold — not far from the recently restored depot at Milepost 114.5.

Historic sites along the 1862 chase route include the following:

- marker near Big Shanty Museum

- Shelbyville[7]

- []

Kennesaw House, 21 Depot St. (c.1845), a hotel on the L&N railway in Marietta, Georgia, is a contributing building in the Northwest Marietta Historic District. In 1862 this was the Fletcher House hotel where the Andrews Raiders stayed the night before commandeering The General.[8]

In Atlanta

In the city of Atlanta, the main Great Locomotive Chase site is The Texas locomotive, located at the Atlanta History Center. In addition, there are historical markers for the sites where James Andrews was hanged on June 7, 1862, near present-day 3rd and Juniper streets, and the mass-hanging on June 18 of seven other Andrews raiders.[9] Pursuers William Fuller and Anthony Murphy are both buried at the Oakland Cemetery[10] The executed raiders were also interred there until being moved to the National Cemetary at Chattanooga, and there is a historical marker at Oakland describing the Great Locomotive Chase.

Bibliography

- Bonds, Russell S. (2006). Stealing the General: The Great Locomotive Chase and the First Medal of Honor. Westholme Publishing. ISBN 1-59416-033-3.

- Gross, Parlee C. (1963). The Case of Private Smith.and the Remaining Mysteries of the Andrews Raid. General Publishing Company.

- O'Neill, Charles (1959). Wild Train: The Story of the Andrews Raiders. New York, NY: Random House.

- Pittenger, William (1885). The great locomotive chase; a history of the Andrews railroad raid into Georgia in 1862,. New York, NY: J.B. Alden.

- Pittenger, William (1881). Capturing a Locomotive: A History of Secret Service in the Late War. Washington DC: The National Tribune.

- Pittenger, Lieut. William (1863). Daring and Suffering: A History of the Great Railroad Adventure. J. W. Daughaday.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2009). The Great Locomotive Chase – The Andrews Raid 1862. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-400-8.

Example [11]

Andrews Raiders

| The Andrews Raiders | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | March 1862 - March 1863 |

| Disbanded | April 1862 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Clandestine operation |

| Role | Infantry |

| Size | 24 |

| Part of | Army of the Ohio, 3rd Division

|

| Patron | Don Carlos Buell, Ormsby M. Mitchel |

| Engagements | Great Locomotive Chase |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | James J. Andrews |

To destroy the railroad, Mitchel assigned one

As ordered, all arrived in Chattanooga at the assigned time. Andrews informed the men that he encountered that he was going to delay the raid by one day owing to wet weather that he expected would delay Mitchel enroute to

Sitting down to breakfast, Conductor

List of monuments of the Great Locomotive Chase

The Ohio monument dedicated to the Andrews Raiders is located at the Chattanooga National Cemetery. There is a scale model of the General on top of the monument, and a brief history of the Great Locomotive Chase. The General is now in the Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History, Kennesaw, Georgia, while the Texas is on display at the Atlanta History Center.

One marker indicates where the chase began, near the Big Shanty Museum (now known as Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History) in Kennesaw, while another shows where the chase ended at Milepost 116.3, north of Ringgold — not far from the recently restored depot at Milepost 114.5.

Historic sites along the 1862 chase route include the following:

- marker near Big Shanty Museum

- Big Shanty Village Historic District

- Camp McDonald

- Acworth Downtown Historic District

- Tarleton Moore House

- Grand Theater (Cartersville, Georgia)

- Old Bartow County Courthouse, now the Bartow History Museum, built so close to the railroad that court was interrupted when any train passed, not built until 1869

- Adairsville Historic District

- the Calhoun Depot, built in 1852-53, at Calhoun, 10 miles north of Adairsville.[6]

- Calhoun Downtown Historic District

- William Taylor House (Resaca, Georgia), associated with northern Georgia soldiers who fought for the Union in the Civil War, though house not built until 1913

- Masonic Lodge No. 238, not built until 1915

- Dalton Commercial Historic District

- Western and Atlantic Depot, Dalton, Georgia

- Crown Mill Historic District

- Western and Atlantic Railroad Tunnel at Tunnel Hill

- Ringgold Gap Battlefield, gap between White Oak Mountain and Taylor Ridge through which railway runs, site of November 1863 battle protecting Confederate retreat after Battle of Missionary Ridge at Chattanooga

- Ringgold Depot

- Ringgold Commercial Historic District

- marker at milepost 116.3

Kennesaw House, 21 Depot St. (c.1845), a hotel on the L&N railway in Marietta, Georgia, is a contributing building in the Northwest Marietta Historic District. In 1862 this was the Fletcher House hotel where the Andrews Raiders stayed the night before commandeering The General.[8]

Finally, there is a historical marker in downtown Atlanta, at the corner of 3rd and Juniper streets, at the site where Andrews was hanged.

- ^ Hughes, Micheal Anderson (1991). "The Struggle for Chattanooga, 1862-1863". p. 10 – via ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

- ^ Cline, Wayne (1997). Alabama Railroads. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press. p. 4.

- ^ Bowery Jr 2014, p. 36.

- ^ Bowery Jr 2014, p. 40.

- ^ Prokopowicz 2014, p. 1.

- ^ a b Kenneth H. Thomas, Jr. (June 22, 1982). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Calhoun Depot". National Park Service. Retrieved August 10, 2016. with nine photos from 1981

- ^ https://www.t-g.com/story/2463205.html

- ^ a b David T. Agnew and Elizabeth Z. Macgregor (April 7, 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Northwest Marietta Historic District". National Park Service. Retrieved September 11, 2016. with 18 photos from 1974-75; #16 shows Kennesaw House

- ^ Site of Andrews Raiders hanging

- ^ Stealing the General

- ^ DeMaria & Wilson 2004, p. 282.