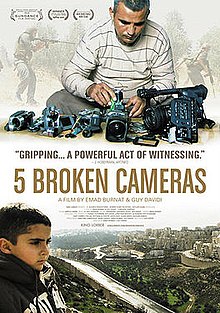

5 Broken Cameras

| 5 Broken Cameras | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Cinematography | Emad Burnat |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Le Trio Joubran |

| Distributed by | Kino Lorber |

Release date |

|

Running time | 94 minutes |

| Countries | State of Palestine Israel France |

| Languages |

|

| Box office | $108,541 (USA) (15 February 2013))[1] |

5 Broken Cameras (

.Synopsis

When his fourth son, Gibreel, is born in 2005, self-taught cameraman Emad Burnat, a Palestinian villager, gets his first camera. At the same time in his village of Bil'in, the Israelis begin bulldozing village olive groves to build a barrier to separate Bil'in from the Jewish settlement Modi'in Illit. The barrier's route cuts off 60% of Bil'in farmland and the villagers resist this seizure of more of their land by the settlers.

During the next year, Burnat films this struggle, which is led by two of his best friends including his brother Iyad. At the same time, Burnat uses the camera to record the growth of his son. Very soon, these events begin to affect his family and his own life. Burnat films the army and police beating and arresting villagers and activists who come to support them. Settlers destroy Palestinian olive trees and attack Burnat when he tries to film them. The army raids the village in the middle of the night to arrest children. He, his friends, and brothers are arrested or shot; some are killed. Each camera used to document these events is shot or smashed.

Eventually, in 2009, Burnat approaches Guy Davidi,[5] an Israeli filmmaker, and the two of them create the film from these five broken cameras and the stories that they represent.

Production

Background and Emad Burnat

Israel began construction of an Israeli West Bank barrier in the West Bank village of Bil'in, Palestine in 2005.[6] Discovering that the wall would cut through their agricultural land, confiscating half of it, the villagers initiated popular protests and were joined by Israeli and international activists.[citation needed] At that point Burnat received a camera to document the movement.

In 2007 the

The first year, Burnat filmed mainly to serve the purposes of activists. His footage was introduced as evidence in Israeli court and posted on YouTube to spread awareness of the growing movement.

As media interest in Bil'in grew, Burnat's footage gained international recognition and was used by local and international news agencies. He started working as a freelance photographer for Reuters and provided footage documenting the villagers' fight to professional filmmakers. This footage was used in such notable films as Shai Carmeli Pollac's Bil'in, My Love and Guy Davidi's and Alesandre Goetschmann's Interrupted Streams.[2]

Pre-Production and Guy Davidi

Burnat was approached in 2009 by Greenhouse, a Mediterranean film development project, to develop a documentary. The project focused on the non-violent movement and especially on Bassem Abu-Rahme, who was killed earlier that year at a demonstration in Bil'in. After some difficulties, Burnat approached Israeli filmmaker Guy Davidi who had just finished editing Interrupted Streams, Davidi's first feature documentary, which was released in 2010 at the Jerusalem International Film Festival.

Earlier, Davidi had been involved in the left-wing organizations Indymedia and Anarchists Against the Wall.[8] "Until my twenties," Davidi has said in an interview, "it was very hard for me to work in Israel. I felt it was a very destructive environment, a very violent environment.... There is a lot of aggression expressed towards the arts in Israel. I connect it completely with the political situation.... So I left for Paris and I found time to reflect on my life.... I kind of found a freedom in Paris and I wanted to express it as well in Israel. And ever since[,] my life was connected with the West Bank."[9]

Davidi provided Burnat's film with a new concept: Burnat himself, the cameraman, would be the protagonist, and the story would be told from his point of view. Davidi also proposed that the film be structured around the history of the destruction of Burnat's cameras. Footage that Burnat shot of his family was also incorporated into the film.

Beginning in 2009, Burnat, adhering to the new concept for the film, focused more extensively on his family's reactions to events. A few important scenes shot by other cameramen (including Guy Davidi) were used to supplement the narrative, and to introduce Burnat as a character.[2]

Editing

Starting in 2009, Davidi worked on the voice-overs and structuring the film. In 2011 French editor Véronique Lagoarde–Ségot joined the project to edit the final cut of the 90-minute film and to create the 52-minute television version. The film takes the form of a diary, and is divided into 5 sections, each of which recounts the story of one of the five cameras that Burnat used over the years.

In a prologue, Burnat is shown with his 5 broken cameras laid out on a table. This scene is returned to at the end of the film. Title cards identifying the time periods during which each camera was used are shown at the start of each episode as well as the epilogue. The story shifts frequently between the dramatic public events in the village and the highly intimate scenes involving Burnat's family.

The most prominent narrative is of Burnat's fourth son Gibreel, whose growth throughout almost 6 years is documented in the film. The birth of Gibreel occurs at the same time as the birth of the non-violent movement in the village; later in the film, Gibreel's first words are "wall" and "cartridge", uttered when he crosses the barrier with his brothers and finally writes his name on the second concrete wall at the end of the film.

Beginning with the episode involving the third camera, the personal and village movement narratives grow more integrated. Burnat becomes more conspicuous as a protagonist. First he is placed under house arrest and films himself, then he is filmed at the moment a bullet directly hits his third camera.[2]

Funding

The film was initially developed by the

Reception

5 Broken Cameras has received positive reviews from numerous critics. It has a fresh rating of 96%, based on 48 reviews at Rotten Tomatoes.[10] It also has a score of 78 out of 100 on Metacritic, based on 15 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[11]

Reception in Israel

The film was released in Israel in July 2012 and immediately won the Best Documentary Award at the

There was also considerable negative response to the film in Israel, however. Davidi said that when he first screened the film for Israeli high school students, "they got angry at me, accused me of lying and being a traitor. But the anger is really against the whole system that lied to them.... So I tell the kids, 'Go ahead and get mad at me. Take it all out on me. Soon you will realize that your anger is not against me, but against the whole system that lied to you.'"[8] According to the AP, the film "has infuriated people on both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian divide", with some Israelis "asking why the government helped fund a film so scathing in its criticism of its own policies, while Palestinians are shocked that the film is winning accolades for being 'Israeli.'"[16] The Israeli nonprofit Consensus petitioned the Israeli Attorney General claiming that Davidi and Burnat "should be charged with slander and prosecuted for 'incitement.'"[17]

Reaction to the Oscar Nomination in Israel

When the film was nominated for an Oscar, the Israeli media referred to it as an Israeli film that would be representing Israel at the Academy Awards, even though the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences does not consider films nominated in the documentary category as representing their countries of origin. In addition, the fact that the film was also a Palestinian work often went unmentioned. Davidi sparked controversy and was criticized by Israeli officials when he stated in an interview that "he does not represent Israel, only himself."

There was considerable controversy over whether the film should be identified as an Israeli or Palestinian production. Burnat described it as a "Palestinian film" while Davidi said it was "first and foremost...a Palestinian film" in contradiction of the Israeli embassy in the United States which in a tweet identified it as an Israeli film.[17] Davidi told The Forward that "the film is not representing a country" and for him "films have no nationalities; the film is a Palestinian-Israeli-French co-production, [with] Israeli and Palestinian directors and a story that is told [with] Palestinian characters and in the West Bank."[18]

Palestinian response

Burnat was criticized in Ramallah for working with Israelis, and Davidi was made to feel that "I had not sufficiently proved myself. I thought to myself that maybe we needed an Israeli activist to die in order to win credibility. Perhaps not enough Israeli blood has been spilled."[8]

Awards

5 Broken Cameras won the World Cinema Directing Award at the

5 Broken Cameras was nominated for Best Documentary Feature in the 85th Academy Awards,[22] and for the Asia Pacific Screen Award for Best Documentary of 2012.[21]

See also

References

- IMDb

- ^ a b c d Official website

- ^ a b "International Emmy Award Official website". Archived from the original on 2007-12-05. Retrieved 2014-07-10.

- ^ a b "'5 Broken Cameras' clinches International Emmy Award, November 26, 2013, Haaretz". Haaretz.

- ^ "5 Broken Cameras: Guy Davidi Interview - TAKE ONE". 4 November 2012. Retrieved 5 Nov 2012.

- ^ a b Kershner, Isabel (5 September 2007). "Israeli Court Orders Barrier Rerouted". New York Times. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Scott, A.O. (29 May 2012). "A Palestinian Whose Cameras Are Witnesses and Casualties of Conflict". New York Times. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Goldman, Lisa (Feb 24, 2013). "'5 Broken Cameras' director: There is no room for guilt - only taking responsibility". 972 Magazine.

- ^ Robbins, Jonathan (May 30, 2012). "Interview With Guy Davidi, "5 Broken Cameras"". Film Society Lincoln Center.

- ^ "5 Broken Cameras". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ "5 Broken Cameras". Metacritic.

- Scott, A.O. (May 29, 2012). "A Palestinian Whose Cameras Are Witnesses and Casualties of Conflict '5 Broken Cameras' Shows Life in One Palestinian Village". The New York Times. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- Artinfo. Artinfo.com. Archived from the originalon August 25, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- Time Out New York.

- ^ Abramson, Larry (Feb 20, 2013). "A West Bank Story, Told Through Palestinian Eyes". NPR.

- ^ "'5 Broken Cameras' angers both sides". SF Gate. Feb 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Shea, Danny (Mar 14, 2013). "Guy Davidi, '5 Broken Cameras' Co-Director, Responds To Slander Claims: 'Disturbing' (VIDEO)". The Huffington Post.

- ^ Seliger, Ralph (5 February 2020). "Why Oscar Nominee Doesn't Represent Israel". The Forward.

- ^ "2012 Sundance Film Festival Announces Awards". Archived from the original on 2012-04-28. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ^ "JVF film 5 Broken Cameras wins IDFA Audience Award". Archived from the original on 2012-02-02. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ a b "5 Broken Cameras: Awards". IMDB.

- ^ "2013 Oscar Nominees". Archived from the original on 2013-01-10. Retrieved 2013-01-12.