Blue runner

| Blue runner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Carangiformes |

| Family: | Carangidae |

| Genus: | Caranx |

| Species: | C. crysos

|

| Binomial name | |

| Caranx crysos (

Mitchill , 1815) | |

| |

| Approximate range of the blue runner | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

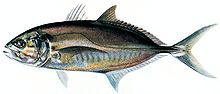

The blue runner (Caranx crysos), also known as the bluestripe jack, Egyptian scad, hardtail jack or hardnose, is a common

The blue runner is a schooling,

Taxonomy and naming

The blue runner is classified within the genus Caranx, one of a number of groups known as the jacks or trevallies. Caranx itself is part of the larger jack and horse mackerel family Carangidae, part of the order Carangiformes.[2]

The species was first

There have been suggestions that the blue runner may be

Description

The blue runner is moderately large in size, growing to a maximum confirmed length of 70 cm and 5.05 kg in mass, but is more common at lengths less than 35 cm.

The blue runner's colour varies from bluish green to olive green dorsally, becoming silvery grey to brassy below. Juveniles often have 7 dark vertical bands on their body. Fin colour also varies, with all fins ranging from to dusky or hyaline to olive green. The species also has a dusky spot which may not be distinct on the upper operculum.[11][12]

Distribution

The blue runner is extensively distributed throughout the tropical and

In the eastern Atlantic the southernmost record is from

Habitat

Blue runner are easily attracted to any large underwater or floating device, either natural or man made. Several studies have shown the species congregates around floating buoy-like fish aggregating devices (FADs), both in shallower waters, as well as in extremely deep (2500 m) waters, indicating the species may move around pelagically.[20] In these situations, blue runner always form small aggregations at the water surface, while other larger species tend to congregate slightly deeper.[20] A number of investigations around oil and gas platforms in the Gulf of Mexico have found blue runner congregate in large numbers around these in the warmer months, where they modify their feeding behavior to take advantage of the structure.[21] Purpose-built artificial reefs[22] and marine aquaculture cage structures are also known to attract the species, with the former having the added benefit of dispersing wayward food scraps.[23]

Biology

The blue runner normally moves either in small

Diet and feeding

The blue runner is a fast-swimming

Studies around these platforms has found blue runner feed with equal intensity during both day and night, with larger prey such as fish taken preferentially at night, with smaller crustaceans taken during the day.[28] Blue runner are one of a number of carangids known to forage in small schools alongside actively feeding spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris), taking advantage of any scraps of food left by the feeding mammals, or any organisms displaced while they forage.[29] The species is also known to eat the dolphins excrement.[29] As well as being important predators, they are also important prey to many larger species including fishes, birds and dolphins.[4][30]

Reproduction and growth

The blue runner reaches sexual maturity at slightly different lengths throughout its range, with all such studies occurring in the west Atlantic. Research in northwest Florida found a length at maturity of 267 mm,[31] a study in Louisiana showed the species reaches sexual maturity at 247–267 mm in females and 225 mm in males, and in Jamaica lengths of 260 mm for males and 280 for females were estimated.[32] Spawning appears to occur offshore year round, although several peaks in spawning activity have been found in different areas through the species range. Peak spawning season in the Gulf of Mexico occurs from June to August, with a secondary peak in spawning during October in northwest Florida.[31] Elsewhere, peaks in larval abundance indicate spawning in the warmer summer months between January and August.[32] Each female releases between 41,000 and 1,546,000 eggs on average, with larger fish producing more eggs.[31] Both the eggs and larvae are pelagic.[33]

The blue runner's larval stage has been extensively described, with distinguishing features including a slightly shallower body than other larval Caranx, and a heavily pigmented head and body.[34] During this early juvenile stage, there are several dark vertical bars clearly present on the side.[34] Larvae and small juveniles remain offshore, living either at depths of around 10 to 20 m,[32] or congregating around floating objects, particularly Sargassum mats and large jellyfish.[35] As the fish grow, they often move to more inshore lagoons and reefs, before slowly making their way to deeper outer reefs at the onset of sexual maturity.[5] Absolute growth rates are not well known, but the species has all the adult characteristics by a length of 59.3 mm.[36] In all cases studied, there are more females in the adult population than males, with female to male ratios ranging from 1.15F:1M to 1.91F:1M.[31] Annual mortality rates for the population in the Gulf of Mexico range from 0.41 to 0.53. The oldest known individual was 11 years old based on otolith rings.[19]

Relationship to humans

The blue runner is a highly important species to commercial

Blue runner is also of high importance to recreational fisheries, with

References

- . Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6. Archived from the originalon 8 April 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ a b Mitchill, S.L. (1815). "The fishes of New York described and arranged". Transactions of the Literary and Philosophical Society of New York. 1. Van Winkle and Wiley: 355–492.

- ^ a b c d e f g Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2009). "Caranx crysos" in FishBase. May 2009 version.

- ^ ISBN 971-10-2201-X.

- ISBN 978-0-906301-88-3.

- ^ JSTOR 1435930.

- ISBN 92-5-303409-2.

- PMID 12099802.

- ^ ISBN 92-5-104827-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Fischer, W; Bianchi, G.; Scott, W.B. (1981). FAO Species Identification Sheets for Fishery Purposes: Eastern Central Atlantic Vol 1. Ottawa: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-292-70634-7.

- ^ Berry, F.H. (1960). "Scale and scute development of the carangid fish Caranx crysos (Mitchill)". Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences. 23: 59–66.

- ISSN 1175-5326.

- ISSN 0074-0195.

- S2CID 84294903.

- ISSN 0210-945X.

- ISSN 0185-3287.

- ^ ISSN 0148-9836.

- ^ S2CID 17177578.

- ^ ISSN 0892-2284.

- ISSN 0749-0208.

- ISSN 1123-4245.

- ^ a b Martins, R.S.; M.J.A. Perez (2008). "Artisanal Fish-Trap Fishery Around Santa Catarina Island During Spring/Summer: Characteristics, Species Interactions and the Influence of the Winds on the Catches" (PDF). Boletim do Instituto de Pesca. 34 (3): 413–423. Retrieved 22 May 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ISSN 0081-8720.

- ^ da Silva Monteiro, V.M. (1998). Peixes de Cabo Verde. Lisbon: Ministério do Mar, Gabinete do Secretário de Estado da Cultura. M2- Artes Gráficas, Lda. p. 179.

- ISSN 1123-4245.

- ^ a b Keenan, S.F.; M.C. Benfield (2003). Importance of zooplankton in the diets of Blue Runner (Caranx crysos) near offshore petroleum platforms in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. OCS Study MMS 2003-029. New Orleans: Coastal Fisheries Institute, Louisiana State University. U.S. Dept. of the Interior. p. 129.

- ^ .

- ^ Beltran-Pedrerosde, S.; T.M. Araujo Pantoja (2006). "Feeding habits of Sotalia fluviatilis in the amazonian estuary". Acta Scientiarum Biological Sciences. 28 (4): 389–393. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ ISSN 0148-9836.

- ^ a b c Shaw, R.F.; D.L. Drullinger (1990). "Early-Life-History Profiles, Seasonal Abundance, and Distribution of Four Species of Carangid Larvae off Louisiana, 1982 and 1983". NOAA Technical Report NMFS. 89. US Department of Commerce: 1–44.

- ISSN 1110-0354.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8493-1916-7.

- ^ Wells, R.J.D.; J.R. Rooker (2004). "Spatial and temporal patterns of habitat use by fishes associated with Sargassum mats in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico" (PDF). Bulletin of Marine Science. 74 (1): 81–99. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ISSN 1110-5348.

- ^ a b Fisheries and Agricultural Organisation. "Global Production Statistics 1950–2007". Blue runner. FAO. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- .

- ISBN 0-9707493-5-X.

- ISBN 978-1-60239-119-2.

- ^ "Record Details". igfa.org. International Game Fish Association.

- ^ "Record History". igfa.org. International Game Fish Association. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- PMID 7200733.

External links

- Blue runner (Caranx crysos) at FishBase

- Blue runner (Caranx crysos) at Gulf of Maine Research Institute

- Blue runner (Caranx crysos) at Indian River

- Blue runner (Caranx crysos) Archived 15 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine at Fishing-boating.com Archived 15 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Blue runner (Caranx crysos) at Combat Fishing

- Photos of Blue runner on Sealife Collection