Conceptual art

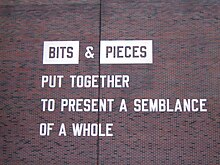

Conceptual art, also referred to as conceptualism, is art in which the concept(s) or idea(s) involved in the work are prioritized equally to or more than traditional aesthetic, technical, and material concerns. Some works of conceptual art may be constructed by anyone simply by following a set of written instructions.[1] This method was fundamental to American artist Sol LeWitt's definition of conceptual art, one of the first to appear in print:

In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.[2]

Tony Godfrey, author of Conceptual Art (Art & Ideas) (1998), asserts that conceptual art questions the nature of art,

Through its association with the Young British Artists and the Turner Prize during the 1990s, in popular usage, particularly in the United Kingdom, "conceptual art" came to denote all contemporary art that does not practice the traditional skills of painting and sculpture.[7] One of the reasons why the term "conceptual art" has come to be associated with various contemporary practices far removed from its original aims and forms lies in the problem of defining the term itself. As the artist Mel Bochner suggested as early as 1970, in explaining why he does not like the epithet "conceptual", it is not always entirely clear what "concept" refers to, and it runs the risk of being confused with "intention". Thus, in describing or defining a work of art as conceptual it is important not to confuse what is referred to as "conceptual" with an artist's "intention".

Precursors

The French artist

In 1956 the founder of

Origins

In 1961, philosopher and artist Henry Flynt coined the term "concept art" in an article bearing the same name which appeared in the proto-Fluxus publication An Anthology of Chance Operations.[9] Flynt's concept art, he maintained, devolved from his notion of "cognitive nihilism", in which paradoxes in logic are shown to evacuate concepts of substance. Drawing on the syntax of logic and mathematics, concept art was meant jointly to supersede mathematics and the formalistic music then current in serious art music circles.[10] Therefore, Flynt maintained, to merit the label concept art, a work had to be a critique of logic or mathematics in which a linguistic concept was the material, a quality which is absent from subsequent "conceptual art".[11]

The term assumed a different meaning when employed by Joseph Kosuth and by the English

The critique of formalism and of the commodification of art

Conceptual art emerged as a movement during the 1960s – in part as a reaction against formalism as then articulated by the influential New York art critic Clement Greenberg. According to Greenberg Modern art followed a process of progressive reduction and refinement toward the goal of defining the essential, formal nature of each medium. Those elements that ran counter to this nature were to be reduced. The task of painting, for example, was to define precisely what kind of object a painting truly is: what makes it a painting and nothing else. As it is of the nature of paintings to be flat objects with canvas surfaces onto which colored pigment is applied, such things as figuration, 3-D perspective illusion and references to external subject matter were all found to be extraneous to the essence of painting, and ought to be removed.[13]

Some have argued that conceptual art continued this "dematerialization" of art by removing the need for objects altogether,[14] while others, including many of the artists themselves, saw conceptual art as a radical break with Greenberg's kind of formalist Modernism. Later artists continued to share a preference for art to be self-critical, as well as a distaste for illusion. However, by the end of the 1960s it was certainly clear that Greenberg's stipulations for art to continue within the confines of each medium and to exclude external subject matter no longer held traction.[15] Conceptual art also reacted against the commodification of art; it attempted a subversion of the gallery or museum as the location and determiner of art, and the art market as the owner and distributor of art. Lawrence Weiner said: "Once you know about a work of mine you own it. There's no way I can climb inside somebody's head and remove it." Many conceptual artists' work can therefore only be known about through documentation which is manifested by it, e.g., photographs, written texts or displayed objects, which some might argue are not in and of themselves the art. It is sometimes (as in the work of Robert Barry, Yoko Ono, and Weiner himself) reduced to a set of written instructions describing a work, but stopping short of actually making it—emphasising the idea as more important than the artifact. This reveals an explicit preference for the "art" side of the ostensible dichotomy between art and craft, where art, unlike craft, takes place within and engages historical discourse: for example, Ono's "written instructions" make more sense alongside other conceptual art of the time.

Language and/as art

Language was a central concern for the first wave of conceptual artists of the 1960s and early 1970s. Although the utilisation of text in art was in no way novel, only in the 1960s did the artists

The British philosopher and theorist of conceptual art

The American art historian

Contemporary history

Proto-conceptualism has roots in the rise of

Contemporary artists have taken up many of the concerns of the conceptual art movement, while they may or may not term themselves "conceptual artists". Ideas such as anti-commodification, social and/or political critique, and ideas/information as

Revival

Neo-conceptual art describes art practices in the 1980s and particularly 1990s to date that derive from the conceptual art movement of the 1960s and 1970s. These subsequent initiatives have included the Moscow Conceptualists, United States neo-conceptualists such as Sherrie Levine and the Young British Artists, notably Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin in the United Kingdom.

Notable examples

- 1913 : Bicycle Wheel (Roue de bicyclette) by Marcel Duchamp. Assisted readymade. Bicycle wheel mounted by its fork on a painted wooden stool. The first readymade, even though he did not have the idea for readymades until two years later. The original was lost. Also, recognized as the first kinetic sculpture.[24]

- 1914 : Bottle Rack (also called Bottle Dryer or Hedgehog) (Egouttoir or Porte-bouteilles or Hérisson) by Marcel Duchamp. Readymade. A galvanized iron bottle drying rack that Duchamp bought as an "already made" sculpture, but it gathered dust in the corner of his Paris studio. Two years later in 1916, in correspondence from New York with his sister, Suzanne Duchamp in France, he expresses a desire to make it a readymade. Suzanne, looking after his Paris studio, has already disposed of it.

- 1915 : In Advance of the Broken Arm (En prévision du bras cassé) by Marcel Duchamp. Readymade. Snow shovel on which Duchamp carefully painted its title. The first piece the artist officially called a "readymade".

- 1916–17 : Apolinère Enameled, 1916–1917. Rectified readymade. An altered Sapolin paint advertisement.

- 1917 : Fountain by Marcel Duchamp, described in an article in The Independent as the invention of conceptual art. It is also an early example of an Institutional Critique[25]

- 1917 : Hat Rack (Porte-chapeaux), c. 1917, by Marcel Duchamp. Readymade. A wooden hatrack.[26]

- 1919 : L.H.O.O.Q. by Marcel Duchamp. Rectified readymade. Pencil on a reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa on which he drew a goatee and moustache titled with a coarse pun.[27]

- 1921 : Why Not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy? by Marcel Duchamp. Assisted readymade. Marble cubes in the shape of sugar lumps with a thermometer and cuttle bones in a small bird cage.

- 1921 : Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette by Marcel Duchamp. Assisted readymade. An altered perfume bottle in the original box.[28]

- 1952 : The premiere of American experimental composer John Cage's work, 4′33″, a three-movement composition, performed by pianist David Tudor on August 29, 1952, in Maverick Concert Hall, Woodstock, New York, as part of a recital of contemporary piano music.[29] It is commonly perceived as "four minutes thirty-three seconds of silence".

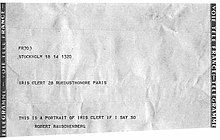

- 1953 : Erased De Kooning Drawing, a drawing by Willem de Kooningwhich Rauschenberg erased. It raised many questions about the fundamental nature of art, challenging the viewer to consider whether erasing another artist's work could be a creative act, as well as whether the work was only "art" because the famous Rauschenberg had done it.

- 1955 : Rhea Sue Sanders creates her first text pieces of the series pièces de complices, combining visual art with poetry and philosophy, and introducing the concept of complicity: the viewer must accomplish the art in her/his imagination.[30]

- 1958: Happenings, Fluxus and Henry Flynt's concept art. Event Scores are simple instructions to complete everyday tasks which can be performed publicly, privately, or not at all.

- 1958: Wolf Vostell Das Theater ist auf der Straße/The theater is on the street. The first Happening in Europe.[32]

- 1961: Piero Manzoni exhibited Artist's Shit, tins purportedly containing his own feces (although since the work would be destroyed if opened, no one has been able to say for sure). He put the tins on sale for their own weight in gold. He also sold his own breath (enclosed in balloons) as Bodies of Air, and signed people's bodies, thus declaring them to be living works of art either for all time or for specified periods. (This depended on how much they are prepared to pay). Marcel Broodthaers and Primo Levi are amongst the designated "artworks".

- 1962: Artist Barrie Bates rebrands himself as Billy Apple, erasing his original identity to continue his exploration of everyday life and commerce as art. By this stage, many of his works are fabricated by third parties.[33]

- 1962: Yves Klein presents Immaterial Pictorial Sensitivity in various ceremonies on the banks of the Seine. He offers to sell his own "pictorial sensitivity" (whatever that was – he did not define it) in exchange for gold leaf. In these ceremonies the purchaser gave Klein the gold leaf in return for a certificate. Since Klein's sensitivity was immaterial, the purchaser was then required to burn the certificate whilst Klein threw half the gold leaf into the Seine. (There were seven purchasers.)

- 1962: FLUXUS Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik in Wiesbaden with George Maciunas, Wolf Vostell, Nam June Paik and others.[34]

- 1963: Water Yam, is published as the first Fluxkit by George Maciunas.

- 1964: Yoko Ono publishes Grapefruit: A Book of Instructions and Drawings, an example of heuristic art, or a series of instructions for how to obtain an aesthetic experience.

- 1965: Art & Language founder Michael Baldwin's Mirror Piece. Instead of paintings, the work shows a variable number of mirrors that challenge both the visitor and Clement Greenberg's theory.[35]

- Joseph Kosuth dates the concept of One and Three Chairs to the year 1965. The presentation of the work consists of a chair, its photo, and an enlargement of a definition of the word "chair". Kosuth chose the definition from a dictionary. Four versions with different definitions are known.

- 1966: Conceived in 1966 The Air Conditioning Show of Art & Language is published as an article in 1967 in the November issue of Arts Magazine.[36]

- 1967: Mel Ramsden's first 100% Abstract Paintings. The painting shows a list of chemical components that constitutes the substance of the painting.[37]

- 1968: Michael Baldwin, Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge and Harold Hurrell found Art & Language.[38]

- 1968: Lawrence Weiner relinquishes the physical making of his work and formulates his "Declaration of Intent", one of the most important conceptual art statements[citation needed] following LeWitt's "Paragraphs on Conceptual Art". The declaration, which underscores his subsequent practice, reads: "1. The artist may construct the piece. 2. The piece may be fabricated. 3. The piece need not be built. Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership."

- 1969: The first generation of New York alternative exhibition spaces are established, including Billy Apple's APPLE, Robert Newman's Gain Ground, where Vito Acconci produced many important early works, and 112 Greene Street.[33][39]

- 1973-1979: Mary Kelly makes her Post-Partum Document, composed of six separate parts charting the first six years of caring for her son. Through a psychoanalytical and feminist lens, the work explores the mother-child relationship and examines her son's evolving sense of self as well as her own.[40]

- 1982: The opera Victorine by Art & Language was to be performed in the city of Kassel for documenta 7 and shown alongside Art & Language Studio at 3 Wesley Place Painted by Actors, but the performance was cancelled.[41]

- 1990: Ronald Jones included in "Mind Over Matter: Concept and Object" exhibition of "third generation Conceptual artists" at the Whitney Museum of American Art.[42]

- 1991: Ronald Jones exhibits objects and text, art, history and science rooted in grim political reality at Metro Pictures Gallery.[43]

- 1991: Charles Saatchi funds Damien Hirst and the next year in the Saatchi Gallery exhibits his The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, a shark in formaldehyde in a vitrine.

- 1992: Maurizio Bolognini starts to "seal" his Programmed Machines: hundreds of computers are programmed and left to run ad infinitum to generate inexhaustible flows of random images which nobody would see.[44]

- 1999: Tracey Emin is nominated for the Turner Prize. Part of her exhibit is My Bed, her dishevelled bed, surrounded by detritus such as condoms, blood-stained knickers, bottles and her bedroom slippers.

- 2001: Martin Creed wins the Turner Prize for Work No. 227: The lights going on and off, an empty room in which the lights go on and off.[45]

- 2003: damali ayo exhibits at the Center of Contemporary Art, Seattle, WA Flesh Tone #1: Skinned, a collaborative self-portrait where she asked paint mixers from local hardware stores to create house paint to match various parts of her body, while recording the interactions.[46]

- 2005: Simon Starling wins the Turner Prize for Shedboatshed, a wooden shed which he had turned into a boat, floated down the Rhine and turned back into a shed again.[47]

- 2014: Olaf Nicolai creates the Memorial for the Victims of Nazi Military Justice on Vienna's Ballhausplatz after winning an international competition. The inscription on top of the three-step sculpture features a poem by Scottish poet Ian Hamilton Finlay (1924–2006) with just two words: all alone.

- 2019: Maurizio Cattelan sells two editions of Comedian, which appears as a banana duct taped to a wall, for US$120,000 each, garnering significant media attention.[48]

Notable conceptual artists

- Kevin Abosch (born 1969)

- Vito Acconci (1940–2017)

- Bas Jan Ader (1942–1975)

- Vikky Alexander (born 1959)

- Francis Alÿs (born 1959)

- Keith Arnatt (1930–2008)

- Roy Ascott (born 1934)

- Marina Abramović (born 1946)

- Billy Apple (1935-2021)

- Shusaku Arakawa (1936–2010)

- Christopher D'Arcangelo (1955–1979)

- Michael Asher (1943–2012)

- Mireille Astore(born 1961)

- damali ayo (born 1972)

- Abel Azcona (born 1988)

- John Baldessari (1931–2020)

- Adina Bar-On (born 1951)

- NatHalie Braun Barends

- Artur Barrio (born 1945)

- Robert Barry (born 1936)

- Lothar Baumgarten (1944–2018)

- Joseph Beuys (1921–1986)

- Adolf Bierbrauer (1915–2012)

- Mark Bloch (born 1956)

- Mel Bochner (born 1940)

- Marinus Boezem (born 1934)

- Maurizio Bolognini (born 1952)

- Allan Bridge (1945–1995)

- Marcel Broodthaers (1924–1976)

- Stanley Brouwn (1935-2017)

- Chris Burden (1946–2015)

- María Teresa Burga Ruiz (1935–2021)

- Daniel Buren (born 1938)

- Victor Burgin (born 1941)

- Donald Burgy (born 1937)

- Maris Bustamante (born 1949)

- John Cage (1912–1992)

- Cai Guo-Qiang (born 1957)

- Sophie Calle (born 1953)

- Graciela Carnevale (born 1942)

- Roberto Chabet (1937–2013)

- Greg Colson (born 1956)

- Martin Creed (born 1968)

- Cory Danziger (born 1977)

- Jack Daws (born 1970)

- Jeremy Deller (born 1966)

- Agnes Denes (born 1938)

- Jan Dibbets (born 1941)

- Braco Dimitrijević (born 1948)

- Mark Divo (born 1966)

- Brad Downey (born 1980)

- Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968)

- Olafur Eliasson (born 1967)

- Noemí Escandell (1942–2019)

- Ken Feingold (born 1952)

- Teresita Fernández (born 1968)

- Fluxus

- Henry Flynt (born 1940)

- Andrea Fraser (born 1965)

- Jens Galschiøt (born 1954)

- Kendell Geers (born 1968)

- Thierry Geoffroy (born 1961)

- Jochen Gerz (born 1940)

- Gilbert and GeorgeGilbert (born 1943) George (born 1942)

- Manav Gupta (born 1967)

- Felix Gonzalez-Torres(1957–1996)

- Allan Graham (born 1943)

- Dan Graham (1942-2022)

- Genco Gulan (born 1969)

- Hans Haacke (born 1936)

- Iris Häussler (born 1962)

- Irma Hünerfauth (1907–1998)

- Oliver Herring (born 1964)

- Andreas Heusser (born 1976)

- Susan Hiller (1940–2019)

- Jenny Holzer (born 1950)

- Greer Honeywill (born 1945)

- Zhang Huan (born 1965)

- Douglas Huebler (1924–1997)

- David Ireland (1930–2009)

- Alfredo Jaar (born 1956)

- Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

- Ronald Jones (1952–2019)

- Ilya Kabakov (1933-2023)

- On Kawara (1932–2014)

- Jonathon Keats (born 1971)

- Mary Kelly (born 1941)

- Yves Klein (1928–1962)

- John Knight (artist) (born 1945)

- Joseph Kosuth (born 1945)

- Barbara Kruger (born 1945)

- Yayoi Kusama (born 1929)

- Magali Lara (born 1956)

- John Latham (1921–2006)

- Matthieu Laurette (born 1970)

- Sol LeWitt (1928–2007)

- Annette Lemieux (born 1957)

- Elliott Linwood (born 1956)

- Noah Lyon (born 1979)

- Richard Long (born 1945)

- Mark Lombardi (1951–2000)

- George Maciunas (1931–1978)

- Teresa Margolles (born 1963)

- María Evelia Marmolejo (born 1958)

- Piero Manzoni (1933–1963)

- Tom Marioni (born 1937)

- Phyllis Mark (1921–2004)

- Danny Matthys (born 1947)

- Allan McCollum (born 1944)

- Cildo Meireles (born 1948)

- Ana Mendieta (1948-1985)

- Marta Minujín (born 1943)

- Linda Montano (born 1942)

- Robert Morris (artist) (1931–2018)

- N.E. Thing Co. Ltd. (Iain & Ingrid Baxter) Iain (born 1936) Ingrid (born 1938)

- Maurizio Nannucci (born 1939)

- Bruce Nauman (born 1941)

- Olaf Nicolai (born 1962)

- Margaret Noble (born 1972)

- Yoko Ono (born 1933)

- Roman Opałka (1931–2011)

- Dennis Oppenheim (1938–2011)

- Michele Pred (born 1966)

- Adrian Piper (born 1948)

- William Pope.L (1955-2023)

- Liliana Porter (born 1941)

- Dmitri Prigov (1940–2007)

- Guillem Ramos-Poquí (born 1944)

- Charles Recher (1950–2017)

- Jim Ricks (born 1973)

- Lotty Rosenfeld (1943–2020)

- Martha Rosler (born 1943)

- Allen Ruppersberg (born 1944)

- Santiago Sierra (born 1966)

- Bodo Sperling (born 1952)

- Stelarc (born 1946)

- M. Vänçi Stirnemann (born 1951)

- Hiroshi Sugimoto (born 1948)

- Stephanie Syjuco (born 1974)

- Hakan Topal (born 1972)

- Endre Tot (born 1937)

- David Tremlett (born 1945)

- Tucumán arde (1968)

- Jacek Tylicki (born 1951)

- Mierle Laderman Ukeles (born 1939)

- Wolf Vostell (1932–1998)

- Mark Wallinger (born 1959)

- Theodore Wan (1953-1987)

- Gillian Wearing (born 1963)

- Peter Weibel (1945-2023)

- Lawrence Weiner (1942-2021)

- Roger Welch (born 1946)

- Christopher Williams (born 1956)

- xurban collective

- Industry of the Ordinary

- Arne Quinze (born 1971)

See also

References

- ^ "Wall Drawing 811 – Sol LeWitt". Archived from the original on 2 March 2007.

- ^ Sol LeWitt "Paragraphs on Conceptual Art", Artforum, June 1967.

- ISBN 978-0-7148-3388-0.

- ^ Joseph Kosuth, Art After Philosophy (1969). Reprinted in Peter Osborne, Conceptual Art: Themes and Movements, Phaidon, London, 2002. p. 232

- Art-Language The Journal of conceptual art: Introduction (1969). Reprinted in Osborne (2002) p. 230

- ^ Ian Burn, Mel Ramsden: "Notes On Analysis" (1970). Reprinted in Osborne (2003), p. 237. E.g. "The outcome of much of the 'conceptual' work of the past two years has been to carefully clear the air of objects."

- ^ "Turner Prize history: Conceptual art". Tate Gallery. tate.org.uk. Accessed August 8, 2006

- ^ Tony Godfrey, Conceptual Art, London: 1998. p. 28

- ^ "Essay: Concept Art". www.henryflynt.org.

- ^ "The Crystallization of Concept Art in 1961". www.henryflynt.org.

- ^ Henry Flynt, "Concept-Art (1962)", Translated and introduced by Nicolas Feuillie, Les presses du réel, Avant-gardes, Dijon.

- ^ "Conceptual Art (Conceptualism) – Artlex". Archived from the original on May 16, 2013.

- ^ Rorimer, p. 11

- ^ Lucy Lippard & John Chandler, "The Dematerialization of Art", Art International 12:2, February 1968. Reprinted in Osborne (2002), p. 218

- ^ Rorimer, p. 12

- ^ "Ed Ruscha and Photography". The Art Institute of Chicago. 1 March – 1 June 2008. Archived from the original on 31 May 2010. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Anne Rorimer, New Art in the Sixties and Seventies, Thames & Hudson, 2001; p. 71

- ^ Rorimer, p. 76

- ^ Peter Osborne, Conceptual Art: Themes and movements, Phaidon, London, 2002. p. 28

- ^ Osborne (2002), p. 28

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-06. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Conceptual Art – "In 1967, Sol LeWitt published Paragraphs on Conceptual Art (considered by many to be the movement's manifesto) [...]."

- ^ "Conceptual Art – The Art Story". theartstory.org. The Art Story Foundation. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ISBN 1-55859-010-2

- ^ Hensher, Philip (2008-02-20). "The loo that shook the world: Duchamp, Man Ray, Picabi". London: The Independent (Extra). pp. 2–5.

- ^ Judovitz: Unpacking Duchamp, 92–94.

- ^ [1] Marcel Duchamp.net, retrieved December 9, 2009

- ^ Marcel Duchamp, Belle haleine – Eau de voilette, Collection Yves Saint Laurent et Pierre Bergé, Christie's Paris, Lot 37. 23 – 25 February 2009

- ISBN 0-415-93792-2. pp. 69–71, 86, 105, 198, 218, 231.

- ^ Bénédicte Demelas: Des mythes et des réalitées de l'avant-garde française. Presses universitaires de Rennes, 1988

- ^ Kristine Stiles & Peter Selz, Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists' Writings (Second Edition, Revised and Expanded by Kristine Stiles) University of California Press 2012, p. 333

- ^ ChewingTheSun. "Vorschau – Museum Morsbroich".

- ^ a b Byrt, Anthony. "Brand, new". Frieze Magazine. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-3-86678-700-1.

- ^ Tate (2016-04-22), Art & Language – Conceptual Art, Mirrors and Selfies | TateShots, retrieved 2017-07-29

- ^ "Air-Conditioning Show / Air Show / Frameworks 1966–67". www.macba.cat. Archived from the original on 2017-07-29. Retrieved 2017-07-29.

- ^ "ART & LANGUAGE UNCOMPLETED". www.macba.cat. Retrieved 2017-07-29.

- ^ "BBC – Coventry and Warwickshire Culture – Art and Language". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-07-29.

- ^ Terroni, Christelle (7 October 2011). "The Rise and Fall of Alternative Spaces". Books&ideas.net. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ Ventura, Anya. "Motherhood Is Hard Work". Getty. Getty Museum. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ISBN 0-262-58240-6.

- ^ Brenson, Michael (19 October 1990). "Review/Art; In the Arena of the Mind, at the Whitney". The New York Times.

- ^ Smith, Roberta. "Art in review: Ronald Jones Metro Pictures", The New York Times, 27 December 1991. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ISBN 88-87262-47-0.

- ^ "BBC News – ARTS – Creed lights up Turner prize". 10 December 2001.

- ^ "Third Coast Audio Festival Behind the Scenes with damali ayo".

- ^ "The Times & The Sunday Times". www.thetimes.co.uk.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (December 6, 2019). "That Banana on the Wall? At Art Basel Miami It'll Cost You $120,000". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

Further reading

- Books

- Charles Harrison, Essays on Art & Language, MIT Press, 1991

- Charles Harrison, Conceptual Art and Painting: Further essays on Art & Language, MIT press, 2001

- Ermanno Migliorini, Conceptual Art, Florence: 1971

- Klaus Honnef, Concept Art, Cologne: Phaidon, 1972

- Ursula Meyer, ed., Conceptual Art, New York: Dutton, 1972

- Lucy R. Lippard, Six Years: the Dematerialization of the Art Object From 1966 to 1972. 1973. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

- Gregory Battcock, ed., Idea Art: A Critical Anthology, New York: E. P. Dutton, 1973

- Jürgen Schilling, Aktionskunst. Identität von Kunst und Leben? Verlag C.J. Bucher, 1978, ISBN 3-7658-0266-2.

- Juan Vicente Aliaga & José Miguel G. Cortés, ed., Arte Conceptual Revisado/Conceptual Art Revisited, Valencia: Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, 1990

- Thomas Dreher, Konzeptuelle Kunst in Amerika und England zwischen 1963 und 1976 (Thesis Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München), Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1992

- Robert C. Morgan, Conceptual Art: An American Perspective, Jefferson, NC/London: McFarland, 1994

- Robert C. Morgan, Art into Ideas: Essays on Conceptual Art, Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press, 1996

- Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, Art in Theory: 1900–1990, Blackwell Publishing, 1993

- Tony Godfrey, Conceptual Art, London: 1998

- Alexander Alberro & Blake Stimson, ed., Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: MIT Press, 1999

- Michael Newman & Jon Bird, ed., Rewriting Conceptual Art, London: Reaktion, 1999

- Anne Rorimer, New Art in the 60s and 70s: Redefining Reality, London: Thames & Hudson, 2001

- Peter Osborne, Conceptual Art (Themes and Movements), Phaidon, 2002 (See also the external links for Robert Smithson)

- Alexander Alberro. Conceptual art and the politics of publicity. MIT Press, 2003.

- Michael Corris, ed., Conceptual Art: Theory, Practice, Myth, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2004

- Daniel Marzona, Conceptual Art, Cologne: Taschen, 2005

- John Roberts, The Intangibilities of Form: Skill and Deskilling in Art After the Readymade, London and New York: Verso Books, 2007

- Peter Goldie and Elisabeth Schellekens, Who's afraid of conceptual art?, Abingdon [etc.] : Routledge, 2010. – VIII, 152 p. : ill. ; 20 cm ISBN 978-0-415-42282-6pbk

- Essays

- Exhibition catalogues

- Diagram-boxes and Analogue Structures, exh.cat. London: Molton Gallery, 1963.

- January 5–31, 1969, exh.cat., New York: Seth Siegelaub, 1969

- When Attitudes Become Form, exh.cat., Bern: Kunsthalle Bern, 1969

- 557,087, exh.cat., Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 1969

- Konzeption/Conception, exh.cat., Leverkusen: Städt. Museum Leverkusen et al., 1969

- Conceptual Art and Conceptual Aspects, exh.cat., New York: New York Cultural Center, 1970

- Art in the Mind, exh.cat., Oberlin, Ohio: Allen Memorial Art Museum, 1970

- Information, exh.cat., New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1970

- Software, exh.cat., New York: Jewish Museum, 1970

- Situation Concepts, exh.cat., Innsbruck: Forum für aktuelle Kunst, 1971

- Art conceptuel I, exh.cat., Bordeaux: capcMusée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux, 1988

- L'art conceptuel, exh.cat., Paris: ARC–Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1989

- Christian Schlatter, ed., Art Conceptuel Formes Conceptuelles/Conceptual Art Conceptual Forms, exh.cat., Paris: Galerie 1900–2000 and Galerie de Poche, 1990

- Reconsidering the Object of Art: 1965–1975, exh.cat., Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1995

- Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s, exh.cat., New York: Queens Museum of Art, 1999

- Open Systems: Rethinking Art c. 1970, exh.cat., London: Tate Modern, 2005

- Art & Language Uncompleted: The Philippe Méaille Collection, MACBA Press, 2014

- Light Years: Conceptual Art and the Photograph 1964–1977, exh.cat., Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2011

External links

Media related to Conceptual art at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Conceptual art at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Conceptual art at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Conceptual art at Wikiquote- Art & Language Uncompleted: The Philippe Méaille Collection, MACBA

- Official site of the Château de Montsoreau-Museum of Contemporary Art

- Light Years: Conceptual Art and the Photograph, 1964–1977 at the Art Institute of Chicago

- Shellekens, Elisabet. "Conceptual Art". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Sol LeWitt, "Paragraphs on Conceptual Art"

- Conceptualism

- pdf file of An Anthology of Chance Operations (1963) containing Henry Flynt's "Concept Art" essay at UbuWeb

- conceptual artists, books on conceptual art and links to further reading

- Arte Conceptual y Posconceptual. La idea como arte: Duchamp, Beuys, Cage y Fluxus – PDF UCM