Aesthetics

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

Aesthetics (also spelled esthetics) is the branch of

Aesthetics studies natural and artificial sources of experiences and how people form a judgement about those sources of experience. It considers what happens in our minds when we engage with objects or environments such as viewing visual art, listening to music, reading poetry, experiencing a play, watching a fashion show, movie, sports or exploring various aspects of nature.

The philosophy of art specifically studies how artists imagine, create, and perform works of art, as well as how people use, enjoy, and criticize art. Aesthetics considers why people like some works of art and not others, as well as how art can affect our moods and our beliefs.[5] Both aesthetics and the philosophy of art try to find answers to what exactly is art and what makes good art.

Etymology

The word aesthetic is derived from the Ancient Greek αἰσθητικός (aisthētikós, "perceptive, sensitive, pertaining to sensory perception"), which in turn comes from αἰσθάνομαι (aisthánomai, "I perceive, sense, learn") and is related to αἴσθησις (aísthēsis, "perception, sensation").[6] Aesthetics in this central sense has been said to start with the series of articles on "The Pleasures of the Imagination", which the journalist Joseph Addison wrote in the early issues of the magazine The Spectator in 1712.[7]

The term aesthetics was

The term was introduced into the English language by Thomas Carlyle in his Life of Friedrich Schiller (1825).[10]

History of aesthetics

The history of the philosophy of art as aesthetics covering the visual arts, the literary arts, the musical arts and other artists forms of expression can be dated back at least to Aristotle and the ancient Greeks. Aristotle writing of the literary arts in his Poetics stated that epic poetry, tragedy, comedy, dithyrambic poetry, painting, sculpture, music, and dance are all fundamentally acts of mimesis, each varying in imitation by medium, object, and manner.[11][12] Aristotle applies the term mimesis both as a property of a work of art and also as the product of the artist's intention[11] and contends that the audience's realisation of the mimesis is vital to understanding the work itself.[11]

Aristotle states that mimesis is a natural instinct of humanity that separates humans from animals

The forms also differ in their object of imitation. Comedy, for instance, is a dramatic imitation of men worse than average; whereas tragedy imitates men slightly better than average. Lastly, the forms differ in their manner of imitation – through narrative or character, through change or no change, and through drama or no drama.[15] Erich Auerbach has extended the discussion of history of aesthetics in his book titled Mimesis.

Aesthetics and the philosophy of art

Some distinguish aesthetics from the philosophy of art, claiming that the former is the study of beauty and taste while the latter is the study of works of art. But aesthetics typically considers questions of beauty as well as of art. It examines topics such as art works, aesthetic experience, and aesthetic judgement.[16]

Aesthetic experience refers to the sensory contemplation or appreciation of an object (not necessarily a work of art), while artistic judgement refers to the recognition, appreciation or criticism of art in general or a specific work of art. In the words of one philosopher, "Philosophy of art is about art. Aesthetics is about many things—including art. But it is also about our experience of breathtaking landscapes or the pattern of shadows on the wall opposite your office.[17]

Philosophers of art weigh a culturally contingent conception of art versus one that is purely theoretical. They study the varieties of art in relation to their physical, social, and cultural environments. Aesthetic philosophers sometimes also refer to psychological studies to help understand how people see, hear, imagine, think, learn, and act in relation to the materials and problems of art. Aesthetic psychology studies the creative process and the aesthetic experience.[18]

Aesthetic judgement, universals, and ethics

Aesthetics is for the artist as ornithology is for the birds.

Aesthetic judgement

Aesthetics examines affective domain response to an object or phenomenon. Judgements of aesthetic value rely on the ability to discriminate at a sensory level. However, aesthetic judgements usually go beyond sensory discrimination.

For David Hume, delicacy of taste is not merely "the ability to detect all the ingredients in a composition", but also the sensitivity "to pains as well as pleasures, which escape the rest of mankind."[21] Thus, sensory discrimination is linked to capacity for pleasure.

For

Viewer interpretations of beauty may on occasion be observed to possess two concepts of value: aesthetics and taste. Aesthetics is the philosophical notion of beauty. Taste is a result of an education process and awareness of elite cultural values learned through exposure to

The question of whether there are facts about aesthetic judgments belongs to the branch of metaphilosophy known as meta-aesthetics.[26]

Factors involved in aesthetic judgement

Aesthetic judgement is closely tied to

As seen, emotions are conformed to 'cultural' reactions, therefore aesthetics is always characterized by 'regional responses', as Francis Grose was the first to affirm in his Rules for Drawing Caricaturas: With an Essay on Comic Painting (1788), published in W. Hogarth, The Analysis of Beauty, Bagster, London s.d. (1791? [1753]), pp. 1–24. Francis Grose can therefore be claimed to be the first critical 'aesthetic regionalist' in proclaiming the anti-universality of aesthetics in contrast to the perilous and always resurgent dictatorship of beauty.[27] 'Aesthetic Regionalism' can thus be seen as a political statement and stance which vies against any universal notion of beauty to safeguard the counter-tradition of aesthetics related to what has been considered and dubbed un-beautiful just because one's culture does not contemplate it, e.g. Edmund Burke's sublime, what is usually defined as 'primitive' art, or un-harmonious, non-cathartic art, camp art, which 'beauty' posits and creates, dichotomously, as its opposite, without even the need of formal statements, but which will be 'perceived' as ugly.[28]

Likewise, aesthetic judgments may be culturally conditioned to some extent. Victorians in Britain often saw African sculpture as ugly, but just a few decades later, Edwardian audiences saw the same sculptures as beautiful. Evaluations of beauty may well be linked to desirability, perhaps even to sexual desirability. Thus, judgments of aesthetic value can become linked to judgments of economic, political, or moral value.[29] In a current context, a Lamborghini might be judged to be beautiful partly because it is desirable as a status symbol, or it may be judged to be repulsive partly because it signifies over-consumption and offends political or moral values.[30]

The context of its presentation also affects the perception of artwork; artworks presented in a classical museum context are liked more and rated more interesting than when presented in a sterile laboratory context. While specific results depend heavily on the style of the presented artwork, overall, the effect of context proved to be more important for the perception of artwork than the effect of genuineness (whether the artwork was being presented as original or as a facsimile/copy).[31]

Aesthetic judgments can often be very fine-grained and internally contradictory. Likewise aesthetic judgments seem often to be at least partly intellectual and interpretative. What a thing means or symbolizes is often what is being judged. Modern aestheticians have asserted that

A third major topic in the study of aesthetic judgments is how they are unified across art forms. For instance, the source of a painting's beauty has a different character to that of beautiful music, suggesting their aesthetics differ in kind.[32] The distinct inability of language to express aesthetic judgment and the role of social construction further cloud this issue.

Aesthetic universals

The philosopher Denis Dutton identified six universal signatures in human aesthetics:[33]

- Expertise or virtuosity. Humans cultivate, recognize, and admire technical artistic skills.

- Nonutilitarian pleasure. People enjoy art for art's sake, and do not demand that it keep them warm or put food on the table.

- Style. Artistic objects and performances satisfy rules of composition that place them in a recognizable style.

- Criticism. People make a point of judging, appreciating, and interpreting works of art.

- Imitation. With a few important exceptions like abstract painting, works of art simulate experiences of the world.

- Special focus. Art is set aside from ordinary life and made a dramatic focus of experience.

Artists such as

Aesthetic ethics

Aesthetic ethics refers to the idea that human conduct and behaviour ought to be governed by that which is beautiful and attractive. John Dewey[35] has pointed out that the unity of aesthetics and ethics is in fact reflected in our understanding of behaviour being "fair"—the word having a double meaning of attractive and morally acceptable. More recently, James Page[36] has suggested that aesthetic ethics might be taken to form a philosophical rationale for peace education.

Beauty

Beauty is one of the main subjects of aesthetics, together with

Different intuitions commonly associated with beauty and its nature are in conflict with each other, which poses certain difficulties for understanding it.[40][41][42] On the one hand, beauty is ascribed to things as an objective, public feature. On the other hand, it seems to depend on the subjective, emotional response of the observer. It is said, for example, that "beauty is in the eye of the beholder".[43][37] It may be possible to reconcile these intuitions by affirming that it depends both on the objective features of the beautiful thing and the subjective response of the observer. One way to achieve this is to hold that an object is beautiful if it has the power to bring about certain aesthetic experiences in the perceiving subject. This is often combined with the view that the subject needs to have the ability to correctly perceive and judge beauty, sometimes referred to as "sense of taste".[37][41][42] Various conceptions of how to define and understand beauty have been suggested. Classical conceptions emphasize the objective side of beauty by defining it in terms of the relation between the beautiful object as a whole and its parts: the parts should stand in the right proportion to each other and thus compose an integrated harmonious whole.[37][39][42] Hedonist conceptions, on the other hand, focus more on the subjective side by drawing a necessary connection between pleasure and beauty, e.g. that for an object to be beautiful is for it to cause disinterested pleasure.[44] Other conceptions include defining beautiful objects in terms of their value, of a loving attitude towards them or of their function.[45][39][37]

New Criticism and "The Intentional Fallacy"

During the first half of the twentieth century, a significant shift to general aesthetic theory took place which attempted to apply aesthetic theory between various forms of art, including the literary arts and the visual arts, to each other. This resulted in the rise of the New Criticism school and debate concerning the intentional fallacy. At issue was the question of whether the aesthetic intentions of the artist in creating the work of art, whatever its specific form, should be associated with the criticism and evaluation of the final product of the work of art, or, if the work of art should be evaluated on its own merits independent of the intentions of the artist.[citation needed]

In 1946,

In another essay, "

As summarized by Berys Gaut and Livingston in their essay "The Creation of Art": "Structuralist and post-structuralists theorists and critics were sharply critical of many aspects of New Criticism, beginning with the emphasis on aesthetic appreciation and the so-called autonomy of art, but they reiterated the attack on biographical criticisms' assumption that the artist's activities and experience were a privileged critical topic."[47] These authors contend that: "Anti-intentionalists, such as formalists, hold that the intentions involved in the making of art are irrelevant or peripheral to correctly interpreting art. So details of the act of creating a work, though possibly of interest in themselves, have no bearing on the correct interpretation of the work."[48]

Gaut and Livingston define the intentionalists as distinct from formalists stating that: "Intentionalists, unlike formalists, hold that reference to intentions is essential in fixing the correct interpretation of works." They quote Richard Wollheim as stating that, "The task of criticism is the reconstruction of the creative process, where the creative process must in turn be thought of as something not stopping short of, but terminating on, the work of art itself."[48]

Derivative forms of aesthetics

A large number of derivative forms of aesthetics have developed as contemporary and transitory forms of inquiry associated with the field of aesthetics which include the post-modern, psychoanalytic, scientific, and mathematical among others.[citation needed]

Post-modern aesthetics and psychoanalysis

Early-twentieth-century artists, poets and composers challenged existing notions of beauty, broadening the scope of art and aesthetics. In 1941, Eli Siegel, American philosopher and poet, founded Aesthetic Realism, the philosophy that reality itself is aesthetic, and that "The world, art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites."[49][50]

Various attempts have been made to define

The relation of Marxist aesthetics to post-modern aesthetics is still a contentious area of debate.

Aesthetics and science

The field of

Truth in beauty and mathematics

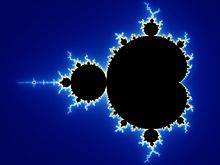

Mathematical considerations, such as

Computational approaches

Computational approaches to aesthetics emerged amid efforts to use computer science methods "to predict, convey, and evoke emotional response to a piece of art.[70] It this field, aesthetics is not considered to be dependent on taste but is a matter of cognition, and, consequently, learning.[71] In 1928, the mathematician George David Birkhoff created an aesthetic measure as the ratio of order to complexity.[72]

In the 1960s and 1970s, Max Bense, Abraham Moles and Frieder Nake were among the first to analyze links between aesthetics, information processing, and information theory.[73][74][75] Max Bense, for example, built on Birkhoff's aesthetic measure and proposed a similar information theoretic measure , where is the redundancy and the entropy, which assigns higher value to simpler artworks.

In the 1990s,

Since about 2005, computer scientists have attempted to develop automated methods to infer aesthetic quality of images.

There have also been relatively successful attempts with regard to chess[further explanation needed] and music.[88] Computational approaches have also been attempted in film making as demonstrated by a software model developed by Chitra Dorai and a group of researchers at the IBM T.J. Watson Research Center.[89] The tool predicted aesthetics based on the values of narrative elements.[89] A relation between Max Bense's mathematical formulation of aesthetics in terms of "redundancy" and "complexity" and theories of musical anticipation was offered using the notion of Information Rate.[90]

Evolutionary aesthetics

Evolutionary aesthetics refers to

Applied aesthetics

As well as being applied to art, aesthetics can also be applied to cultural objects, such as crosses or tools. For example, aesthetic coupling between art-objects and medical topics was made by speakers working for the US Information Agency. Art slides were linked to slides of pharmacological data, which improved attention and retention by simultaneous activation of intuitive right brain with rational left.[92] It can also be used in topics as diverse as cartography, mathematics, gastronomy, fashion and website design.[93][94][95][96][97]

Other approaches

Guy Sircello has pioneered efforts in analytic philosophy to develop a rigorous theory of aesthetics, focusing on the concepts of beauty,[98] love[99] and sublimity.[100] In contrast to romantic theorists, Sircello argued for the objectivity of beauty and formulated a theory of love on that basis.

British philosopher and theorist of

Gary Tedman has put forward a theory of a subjectless aesthetics derived from Karl Marx's concept of alienation, and Louis Althusser's antihumanism, using elements of Freud's group psychology, defining a concept of the 'aesthetic level of practice'.[102]

Gregory Loewen has suggested that the subject is key in the interaction with the aesthetic object. The work of art serves as a vehicle for the projection of the individual's identity into the world of objects, as well as being the irruptive source of much of what is uncanny in modern life. As well, art is used to memorialize individuated biographies in a manner that allows persons to imagine that they are part of something greater than themselves.[103]

Criticism

The philosophy of aesthetics as a practice has been criticized by some sociologists and writers of art and society. Raymond Williams, for example, argues that there is no unique and or individual aesthetic object which can be extrapolated from the art world, but rather that there is a continuum of cultural forms and experience of which ordinary speech and experiences may signal as art. By "art" we may frame several artistic "works" or "creations" as so though this reference remains within the institution or special event which creates it and this leaves some works or other possible "art" outside of the frame work, or other interpretations such as other phenomenon which may not be considered as "art".[104]

Pierre Bourdieu disagrees with Kant's idea of the "aesthetic". He argues that Kant's "aesthetic" merely represents an experience that is the product of an elevated class habitus and scholarly leisure as opposed to other possible and equally valid "aesthetic" experiences which lay outside Kant's narrow definition.[105]

Timothy Laurie argues that theories of musical aesthetics "framed entirely in terms of appreciation, contemplation or reflection risk idealizing an implausibly unmotivated listener defined solely through musical objects, rather than seeing them as a person for whom complex intentions and motivations produce variable attractions to cultural objects and practices".[106]

See also

Philosophy portal

Philosophy portal- Aestheticism

- Aesthetics of science

- Art and Theosophy

- Art periods

- Esthesic and poietic

- Everyday Aesthetics

- History of aesthetics before the 20th century

- Japanese aesthetics

- Medieval aesthetics

- Mise en scène

- Theological aesthetics

- Theory of art

References

- ^ "Aesthetics Archived 31 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine", Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Barry Hartley Slater. Retrieved 28-02-2021.

- ^ Zangwill, Nick. "Aesthetic Judgment Archived 2 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 02-28-2003/10-22-2007. Retrieved 07-24-2008.

- ^ Kelly (1998) p. ix

- .

- ^ Thomas Munro, "Aesthetics", The World Book Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, ed. A. Richard Harmet, et al., (Chicago: Merchandise Mart Plaza, 1986), p. 80

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "aesthetic". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Slater, Barry Hartley. "Aesthetics". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 28 December 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ISBN 978-0521606691.

- ISBN 978-1136788000..

- from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Halliwell 2002, pp. 152–159.

- ^ Poetics, p. I 1447a.

- ^ Poetics, p. IV.

- ^ Halliwell 2002, pp. 152–59.

- ^ Poetics, p. III.

- ^ Shelley, James (2017), "The Concept of the Aesthetic", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2017 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, archived from the original on 8 March 2021, retrieved 9 December 2018

- ^ Nanay, Bence. (2019) Aesthetics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p.4

- ^ Thomas Munro, "aesthetics", The World Book Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, ed. A. Richard Harmet, et al., (Chicago: Merchandise Mart Plaza, 1986), p. 81.

- ^ Barnett Newman Foundation, Chronology, 1952 Archived 8 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 30 August 2010

- ISBN 978-0812695403

- ^ David Hume, Essays Moral, Political, Literary, Indianapolis: Literary Fund, 1987.

- ISBN 9781508892281.

- ISBN 0674212770

- ^ Zangwill, Nick (26 August 2014). "Aesthetic Judgment". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ISBN 978-8301008246.

- ISBN 978-0-19-974710-8– via www.oxfordreference.com.

- ^ Bezrucka, Yvonne (2017). The Invention of Northern Aesthetics in 18th-Century English Literature. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- S2CID 170093813.

- ISBN 8254701741.

- ISBN 978-0631205944.

- from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ Consider Clement Greenberg's arguments in "On Modernist Painting" (1961), reprinted in Aesthetics: A Reader in Philosophy of Arts.

- ^ Denis Dutton's Aesthetic Universals summarized by Steven Pinker in The Blank Slate

- ^ Derek Allan, Art and the Human Adventure: André Malraux's Theory of Art. (Amsterdam: Rodopi. 2009)

- ^ Dewey, John; James Tufts (1932). "Ethics". In Jo-Ann Boydston (ed.). The Collected Works of John Dewey, 1882–1953. Carbonsdale: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 275.

- ISBN 978-1593118891. Archivedfrom the original on 4 November 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2017 – via eprints.qut.edu.au.

Sources

- Aristotle. "Poetics". classics.mit.edu. The Internet Classics Archive. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-691-09258-4.

Further reading

- ISBN 978-1441118509.

- Chung-yuan, Chang (1963–1970). Creativity and Taoism, A Study of Chinese Philosophy, Art, and Poetry. New York: Harper Torchbooks. ISBN 978-0061319686.

- Handbook of Phenomenological Aesthetics. Edited by Hans Rainer Sepp and Lester Embree. (Series: Contributions To Phenomenology, Vol. 59) Springer, Dordrecht / Heidelberg / London / New York 2010. ISBN 978-9048124701

- Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

- Ayn Rand, The Romantic Manifesto: A Philosophy of Literature, New York: New American Library, 1971

- Derek Allan, Art and the Human Adventure, Andre Malraux's Theory of Art, Rodopi, 2009

- Derek Allan. Art and Time, Cambridge Scholars, 2013.

- Augros, Robert M., Stanciu, George N., The New Story of Science: mind and the universe, Lake Bluff, Ill.: Regnery Gateway, 1984. ISBN 0895268337(has significant material on Art, Science and their philosophies)

- John Bender and Gene Blocker, Contemporary Philosophy of Art: Readings in Analytic Aesthetics 1993.

- René Bergeron. L'Art et sa spiritualité. Québec, QC.: Éditions du Pelican, 1961.

- Christine Buci-Glucksmann (2003), Esthétique de l'éphémère, Galilée. (French)

- ISBN 979-12-5482-224-1

- Noël Carroll (2000), Theories of Art Today, University of Wisconsin Press.

- ISBN 8882101657.

- Benedetto Croce (1922), Aesthetic as Science of Expression and General Linguistic.

- E.S. Dallas(1866), The Gay Science, 2 volumes, on the aesthetics of poetry.

- Danto, Arthur (2003), The Abuse of Beauty: Aesthetics and the Concept of Art, Open Court.

- Stephen Davies (1991), Definitions of Art.

- ISBN 0631163026

- Susan L. Feagin and Patrick Maynard (1997), Aesthetics. Oxford Readers.

- Penny Florence and Nicola Foster (eds.) (2000), Differential Aesthetics. London: Ashgate. ISBN 075461493X

- Berys Gaut and Dominic McIver Lopes (eds.), Routledge Companion to Aesthetics. 3rd ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2013.

- Annemarie Gethmann-Siefert (1995), Einführung in die Ästhetik, Munich, W. Fink.

- David Goldblatt and Lee B. Brown, ed. (2010), Aesthetics: A Reader in the Philosophy of the Arts. 3rd ed. Pearson Publishing.

- Theodore Gracyk (2011), The Philosophy of Art: An Introduction. Polity Press.

- Greenberg, Clement (1960), "Modernist Painting", The Collected Essays and Criticism 1957–1969, The University of Chicago Press, 1993, 85–92.

- Evelyn Hatcher (ed.), Art as Culture: An Introduction to the Anthropology of Art. 1999

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1975), Aesthetics. Lectures on Fine Art, trans. T.M. Knox, 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- OCLC 1125858

- Michael Ann Holly and Keith Moxey (eds.), Art History and Visual Studies. Yale University Press, 2002. ISBN 0300097891

- ISBN 026201226X

- Critique of Judgement, Translated by Werner S. Pluhar, Hackett Publishing Co., 1987.

- Kelly, Michael (Editor in Chief) (1998) Encyclopedia of Aesthetics. New York, Oxford, ISBN 978-0195113075. Covers philosophical, historical, sociological, and biographical aspects of Art and Aesthetics worldwide.

- Kent, Alexander J. (2005). "Aesthetics: A Lost Cause in Cartographic Theory?". The Cartographic Journal. 42 (2): 182–188. S2CID 129910488.

- Søren Kierkegaard (1843), Either/Or, translated by Alastair Hannay, London, Penguin, 1992

- Peter Kivy (ed.), The Blackwell Guide to Aesthetics. 2004

- Carolyn Korsmeyer (ed.), Aesthetics: The Big Questions. 1998

- Lyotard, Jean-François (1979), The Postmodern Condition, Manchester University Press, 1984.

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1969), The Visible and the Invisible, Northwestern University Press.

- David Novitz (1992), The Boundaries of Art.

- Mario Perniola, The Art and Its Shadow, foreword by Hugh J. Silverman, translated by Massimo Verdicchio, London-New York, Continuum, 2004.

- ISBN 0631227156.

- ISBN 0415413745.

- ISBN 0415141281.

- George Santayana (1896), The Sense of Beauty. Being the Outlines of Aesthetic Theory. New York, Modern Library, 1955.

- ISBN 978-0691089591

- Friedrich Schiller, (1795), On the Aesthetic Education of Man. Dover Publications, 2004.

- Alan Singer and Allen Dunn (eds.), Literary Aesthetics: A Reader. Blackwell Publishing Limited, 2000. ISBN 978-0631208693

- ISBN 978-1498524568

- ISBN 978-9024722334

- Władysław Tatarkiewicz, History of Aesthetics, 3 vols. (1–2, 1970; 3, 1974), The Hague, Mouton.

- Markand Thakar Looking for the 'Harp' Quartet: An Investigation into Musical Beauty. University of Rochester Press, 2011.

- Leo Tolstoy, What Is Art?, Penguin Classics, 1995.

- ISBN 0199229759

- ISBN 1890318027

- The London Philosophy Study Guide Archived 23 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine offers many suggestions on what to read, depending on the student's familiarity with the subject: Aesthetics Archived 23 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- John M. Valentine, Beginning Aesthetics: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Art. McGraw-Hill, 2006. ISBN 978-0073537542

- von Vacano, Diego, "The Art of Power: Machiavelli, Nietzsche and the Making of Aesthetic Political Theory," Lanham MD: Lexington: 2007.

- Thomas Wartenberg, The Nature of Art. 2006.

- John Whitehead, Grasping for the Wind. 2001.

- Ludwig Wittgenstein, Lectures on aesthetics, psychology and religious belief, Oxford, Blackwell, 1966.

- ISBN 0521297060

- ISBN 978-9004448704

- Ben Shneiderman, The Power of Aesthetic: Enhancing Visual Appeal in Your Designs Archived 20 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Ben, 1968.

- Jean-Marc Rouvière, Au prisme du readymade, incises sur l'identité équivoque de l'objet préface de Philippe Sers et G. Litichevesky, Paris L'Harmattan 2023 ISBN 978-2-14-031710-1

Indian aesthetics

- Wallace Dace (1963). "The Concept of "Rasa" in Sanskrit Dramatic Theory". Educational Theatre Journal. 15 (3): 249–254. JSTOR 3204783.

- René Daumal (1982). Rasa, or, Knowledge of the self: essays on Indian aesthetics and selected Sanskrit studies. New Directions. ISBN 978-0811208246.

- Natalia Lidova (2014). Natyashastra. Oxford University Press. .

- Natalia Lidova (1994). Drama and Ritual of Early Hinduism. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120812345.

- Ananda Lal (2004). The Oxford Companion to Indian Theatre. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195644463.

- Tarla Mehta (1995). Sanskrit Play Production in Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120810570.

- Rowell, Lewis (2015). Music and Musical Thought in Early India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226730349.

- ISBN 978-9004039780.

- Farley P. Richmond; Darius L. Swann; Phillip B. Zarrilli (1993). Indian Theatre: Traditions of Performance. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120809819.

External links

- Aesthetics at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- Aesthetics at PhilPapers

- "Aesthetics". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Aesthetics in Continental Philosophy Archived 1 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine article in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Medieval Theories of Aesthetics Archived 18 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine article in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- "The Value of Art". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Revue online Appareil

- Postscript 1980 – Some Old Problems in New Perspectives Archived 28 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Aesthetics in Art Education: A Look Toward Implementation Archived 5 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- More about Art, culture and Education

- The Concept of the Aesthetic Archived 4 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Aesthetics Archived 29 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine entry in the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Philosophy of Aesthetics entry in the Philosophy Archive

- Washington State Board for Community & Technical Colleges: Introduction to Aesthetics Archived 1 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Beauty Archived 6 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Angie Hobbs, Susan James & Julian Baggini (In Our Time, 19 May 2005)