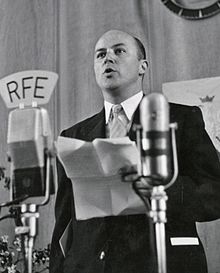

Jan Nowak-Jeziorański

Jan Nowak-Jeziorański (Polish pronunciation:

He was born Zdzisław Antoni Jeziorański, (Jeziora Coat of Arms) in

Biography

Zdzisław Jeziorański was born on 2 October 1914 in Berlin. He attended

He quickly joined the

He also served as an envoy between the commanders of the

During the Uprising Nowak-Jeziorański took an active part in the fight against the Germans and also organised the Polish radio that maintained contact with Allied countries through daily broadcasts in Polish and English. Shortly before the capitulation of the Polish capital, he was ordered by Home Army's commander-in-chief Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski to leave the city and find his way to London. He managed to evade being captured and reached Great Britain, bringing with him large quantities of documents and photos. For his bravery and his travels through the German-occupied Europe he was awarded with the Virtuti Militari, the highest Polish military medal.[6]

After the war Nowak-Jeziorański stayed in the West, initially in London and then in

In the 1990s he started his cooperation with the

For his writings he was awarded some of the most prestigious Polish literary awards, including the

He died in Warsaw on 20 January 2005.[9] He donated all his archives to the Ossolineum Institute.[10]

Censorship in Russia

A selection of Nowak's texts has been confiscated in Saint Petersburg, Russia by the FSB.[11]

Awards

- Knight's Cross of the Virtuti Militari (1944, highest Polish military award)[12]

- Cross of Valour (Krzyż Walecznych)

- Officer's Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta

- Commander's Cross with Star of the Order of Merit of the Polish Republic(1993)

- Order of the White Eagle (highest Polish award, 1994)

- Presidential Medal of Freedom (highest civilian award in the United States, 1996)[13]

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas (the highest Lithuanian civilian award, 1998)[14]

- King's Medal for Courage in the Cause of Freedom (United Kingdom)[15]

- Kisiel Prize (1999)

- Lumen Mundi (2001)

- Ksawery Pruszyński Award (2001)

- Man of Reconciliation (2002), awarded by the Polish Council of Christians and Jews for his contribution to Christian-Jewish dialogue in Poland

- Wiktor Award and Superwiktor (2003) Awards of the Academy of Television

- Gold Statue of the Business Centre Club for his contribution to the development of Polish democracy awarded by Business Centre Club (2003)

- Honorary citizen of Warsaw, Gdansk and Kraków

- Prize. Xavier Pruszynski, granted by the Polish PEN Club

- Golden Microphone

- Diamond Microphone[16]

Bibliography

Among other books, he wrote:

- Polska droga ku wolnosci, 1952–1973, London, 1974. ISBN 0-901342-19-X

- Courier from Warsaw (Kurier z Warszawy, published in London 1978, Polish underground edition 1981, official edition in 1989, published in English in 1982 by Wayne State University Press) ISBN 0-8143-1725-1

- Ideological competition in United States' strategy, Polish American Congress, 1980.

- Polska została sobą, 1980. ISBN 0-902352-16-4

- Wojna w eterze (War on the Radio, memoirs 1948–1956), 1986. ISBN 0-903705-53-2

- Kryptonim "Odra" (Code-name Odra), Warsaw, 1986. ISBN 83-11-07358-9

- Polska z oddali. Wspomnienia 1956–1976 (Poland from the distance), 1988

- Poland and Germany (Occasional paper / East European Studies), Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 1991.

- Z dziejów Armii Krajowej w inspektoracie Płocko-Sierpeckim, ISBN 83-900609-0-6

- W poszukiwaniu nadziei (In Search for Hope), 1993

- Rozmowy o Polsce, Warsaw, 1995. ISBN 83-07-02466-8

- Polska wczoraj, dzis i jutro (Poland today, tomorrow and the day after), Warsaw, 1999. ISBN 83-07-02680-6

- Listy 1952–1998 (Letters 1952–1998), ISBN 83-7095-052-3

- Poland's Road to NATO, Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Ossolineum, Wrocław 2006, ISBN 83-7095-079-5

In popular culture

A dramatic feature film about the wartime experiences of Nowak-Jeziorański and the

See also

- Polish Secret State

References

- ^ "'Courier from Warsaw' commemorated in a movie". Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "THE COURIER FROM WARSAW: JAN JEZIORAŃSKI-NOWAK'S FIGHT FOR POLISH INDEPENDENCE". Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Zdzisław Antoni Jeziorański". Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Jan Nowak-Jeziorański (1914–2005)". Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Jan Nowak-Jeziorański – symbol walki z komunizmem". Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Jan Nowak-Jeziorański (1914–2005)". Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Jan Nowak-Jeziorański (1914–2005)". Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Jan-Nowak Jeziorański. Biogram". Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Jan Nowak-Jeziorański". Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Jan Nowak-Jeziorański (1914–2005) – sylwetka". Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Maciejewska, Beata (18 February 2016). "Książki wrocławskiego wydawnictwa zakazane w Rosji. FSB w drukarni, zarekwirowali cały nakład". wroclaw.wyborcza.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "75 lat temu przerzucono do Polski m.in. Jana Nowaka-Jeziorańskiego". Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "THE COURIER FROM WARSAW: JAN JEZIORAŃSKI-NOWAK'S FIGHT FOR POLISH INDEPENDENCE". Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Valstybės apdovanojimai". Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ISBN 9781317475941. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Rok Nowaka-Jeziorańskiego. "Był sternikiem, ambasadorem, doradcą"" [The year of Nowak-Jeziorański. "He was a helmsman, ambassador, advisor."] (in Polish). Retrieved 16 April 2020.

External links

- BBC Polish World War II underground hero dies accessed 21 January 2005

- Reuters Polish World War II 'Courier from Warsaw' Dies, Aged 91[dead link] accessed 21 January 2005

- Radio Free Europa Legendary RFE Polish Service Director Jan Nowak Dead At 91 accessed 21 January 2005

- Wikinews Jan Nowak-Jezioranski Dies