Kate Douglas Wiggin

Kate Douglas Wiggin | |

|---|---|

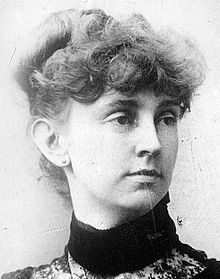

Wiggin depicted in "A Woman of the Century" | |

| Born | Kate Douglas Smith September 28, 1856 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | August 24, 1923 (aged 66) Harrow, Middlesex, England |

| Occupation | Author |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Gorham Female Seminary; Morison Academy (Baltimore) |

| Spouse | Bradley Wiggin, George Christopher Riggs |

| Signature | |

Kate Douglas Wiggin (September 28, 1856 – August 24, 1923) was an American educator, author and composer. She wrote children's stories, most notably the classic children's novel Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm,[1] and composed collections of children's songs. She started the first free kindergarten in San Francisco in 1878 (the Silver Street Free Kindergarten). With her sister during the 1880s, she also established a training school for kindergarten teachers. Kate Wiggin devoted her adult life to the welfare of children in an era when children were commonly thought of as cheap labor.

Wiggin went to California to study kindergarten methods. She began to teach in San Francisco with her sister

Early life

Kate Douglas Smith Wiggin was born in Philadelphia, the daughter of lawyer Robert N. Smith, and of Welsh descent.[3][4][1] Kate experienced a happy childhood, even though it was colored by the American Civil War and her father's death. Kate and her sister Nora were still quite young when their widowed mother moved her little family from Philadelphia to Portland, Maine, then, three years later, upon her remarriage, to the little village of Hollis. There Kate matured in rural surroundings, with her sister and her new baby brother Philip.

Notably, she once met the novelist Charles Dickens. Her mother and another relative had gone to hear Dickens read in Portland, but Wiggin, aged 11, was thought to be too young to warrant an expensive ticket. The following day, she found herself on the same train as Dickens and engaged him in a lively conversation for the course of the journey, an experience which she later detailed in a short memoir titled A Child's Journey with Dickens (1912).

Her education was spotty, consisting of a short stint at a

Early career

In 1873, hoping to ease Albion Bradbury's lung disease, Kate's family moved to Santa Barbara, California, where Kate's stepfather died three years later. A kindergarten training class was opening in Los Angeles under Emma Marwedel (1818–1893),[4][5] and Kate enrolled. After graduation, in 1878, she headed the first free kindergarten in California, on Silver Street in the slums of San Francisco. The children were "street Arabs of the wildest type", but Kate had a loving personality and dramatic flair. By 1880 she was forming a teacher-training school in conjunction with the Silver Street kindergarten.

In 1881, Kate married (Samuel) Bradley Wiggin, a San Francisco lawyer.

Kate Wiggin had no children. She moved to New York City in 1888.[4] When her husband died suddenly in 1889, Kate relocated to Maine. For the rest of her life she grieved, but she also traveled as frequently as she could, dividing her time between writing, visits to Europe, and giving public reading for the benefit of various children's charities.

Wiggin traveled abroad and back from Liverpool in the United Kingdom at least three times. Records from the Ellis Island logs show that she arrived back in New York City from Liverpool in October 1892, July 1893, and July 1894.[7] On the logs for the 1892 trip, Wiggin describes her occupation as "Wife",[8] despite her former husband dying three years prior. In 1893 and 1894, she describes herself as an "Authoress".[9]

Wiggin met dry goods (specifically, linen) importer George Christopher Riggs on her way to England in 1894. The pair are said to have hit it off and had agreed to marry even before the ship docked in England.[10] In the Ellis Island logs from Wiggin's 1894 trip back to New York City from Liverpool, the two sign their names next to each other, indicating their closeness.[11] The pair married in New York City on March 30, 1895, at All Souls Church. George Riggs soon became one of Wiggin's biggest advocates as she became more successful.

After the marriage she continued to write under the name of Wiggin. Her literary output included popular books for adults; with her sister, Nora A. Smith, she published scholarly work on the educational principles of Friedrich Fröbel: Froebel's Gifts (1895), Froebel's Occupations (1896), and Kindergarten Principles and Practice (1896);[4] and she wrote the classic children's novel Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1903), as well as the 1905 best-seller Rose o' the River. Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm became an immediate bestseller; both it and Mother Carey's Chickens (1911) were adapted to the stage. Houghton Mifflin collected her writings in 10 volumes in 1917.

For a time, she lived at

Later life and death

Wiggin was an active and popular hostess in New York and in the community of Upper Largo, Scotland, where she had a summer home and where she organized plays for many years, as detailed in her memoir My Garden of Memory.

In 1921, Wiggin and her sister

Wiggin was also a songwriter and composer. For "Kindergarten Chimes" (1885) and other collections for children, she wrote some of the lyrics, music, and arrangements. For "Nine Love Songs and a Carol" (1896), she composed all of the music.

Legacy

In the 1980s and 1990s, Wiggin's first husband's distant cousin, Eric E. Wiggin, published updated versions of some books in Kate Douglas Wiggin's Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm series. He later published his own addition to the series, entitled, Rebecca Returns to Sunnybrook.[14] Eric E. Wiggin extended Kate Douglas Wiggin's series after years of writing Christian literature, newspaper articles, and other children's books. Eric E. Wiggin's books sold best among his target audience of homeschoolers; with their help, his updated novels and his new addition to the series have sold more than 50,000 copies.[citation needed]

Many of Kate Douglas Wiggin's novels were made into movies. Perhaps the most famous film adaptation of her books is the 1938 film, which stars Shirley Temple.

Selected works

- The Story of Patsy (1883)

- The Birds' Christmas Carol (1887)

- A Summer in a Canyon: A California Story (1889)

- Timothy's Quest (1890), illustrated by Oliver Herford

- Polly Oliver's Problem (1893)

- A Cathedral Courtship, and Penelope's English Experiences (1893)

- The Village Watch-Tower (1895)

- Penelope's Progress (1898)

- Penelope's Travels in Scotland (1898)

- Penelope's Irish Experiences (1901)

- The Diary of a Goose Girl (1902), illus. Claude A. Shepperson

- Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1903)

- Half-a-Dozen Housekeepers (1903)

- Rose o' the River (1905)

- New Chronicles of Rebecca (1907)

- Homespun Tales (1907)

- The Old Peabody Pew (1907)

- Susanna and Sue (1909)

- Mother Carey's Chickens (1911)

- Robinetta (1911)

- A Child's Journey with Dickens (1912)

- The Story of Waitstill Baxter (1913)[15]

- The Romance of a Christmas Card (1916)

- Marm Lisa

- My Garden of Memory (autobiography, published posthumously in 1923)

- With Nora A. Smith

- The Story Hour: a book for the home and kindergarten (1890), LCCN 14-19353

- Golden Numbers: a book of verse for youth, eds. (1902), LCCN 02-27230

- The Posy Ring: a book of verse for children, eds. (1903) – "companion volume", LCCN 03-5775

- The Fairy Ring, eds. (1906); truncated as Fairy Stories Every Child Should Know (1942), illus. Elizabeth MacKinstry LCCN 42-51972

- Magic Casements: A Second Fairy Book, eds. (1907)

- Pinafore Palace: a book of rhymes for the nursery, eds. (1907)

- Tales of Laughter: A Third Fairy Book, eds. (1908)

- The Arabian Nights: their best-known tales, eds. (1909), illus. Maxfield Parrish

- Tales of Wonder: A Fourth Fairy Book, eds. (1909)

- The Talking Beasts: a book of fable wisdom, eds. (1911)

- An Hour with the Fairies (1911)

- Twilight Stories: more tales for the story hour, eds. (1925), LCCN 25-17938

- The Story Hour. A Book for the Home and Kingergarten

- Children's Rights

- The Republic of Childhood (3 volumes)

- Marm Lisa

- About Kate Douglas Wiggin

- Kate Douglas Wiggin as Her Sister Knew Her (1925)

Filmography

- A Bit o' Heaven (1917), directed by Lule Warrenton, based on the novel The Birds' Christmas Carol

- Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1917), starring Mary Pickford, directed by Marshall Neilan (based on the novel Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm)

- Rose o' the River (1919), directed by Robert Thornby (based on the novel Rose o' the River)

- Timothy's Quest (1922), directed by Sidney Olcott (based on the story Timothy's Quest)

- Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1932), directed by Alfred Santell (based on the novel Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm)

- Timothy's Quest (1936), directed by Charles Barton (based on the story Timothy's Quest)

- Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1938), starring Shirley Temple, directed by Allan Dwan (based on the novel Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm)

- Mother Carey's Chickens (1938), directed by Rowland V. Lee (based on the novel Mother Carey's Chickens)

- Summer Magic (1963), a Walt Disney production starring Hayley Mills, directed by James Neilson (based on the novel Mother Carey's Chickens)

- Christmas World: "The Bird's Christmas Carol" (2019), a Once Upon a Tale Entertainment presentation, directed by James Arrow (uncreditedly, based on the novel The Birds' Christmas Carol)

References

- ^ a b Mielewczik, Michael; Jowett, Kelly; Moll, Janine (2019). "Beehives, Booze and Suffragettes: The "Sad Case" of Ellen S. Tupper (1822–1888), the "Bee Woman" and "Iowa Queen Bee"". Entomologie heute. 31: 113–227.

- ^ Rutherford 1894, pp. 640–41.

- ^ Welsh Americans at www.everyculture.com

- ^ New International Encyclopedia(1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- OCLC 4457643.

- ^ "Kate Douglas Wiggin Collection M187". library.bowdoin.edu.

- ^ Ellis Island Records, Type in "Kate D. Wiggin"

- ^ 1892 Ellis Island logs, passenger logs for this ship

- ^ 1893 Ellis island logs, 1893 passenger logs

- ^ "Wiggin, Kate Douglas (1856-1923)", Encyclopedia.com article

- ^ 1894 Ellis Island logs, 1894 ship passenger logs

- ^ My Garden of Memory, pp.365–366

- ISBN 0-684-19340-X, dust jacket copy

- ^ "Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm", Loyal Books, Source explaining Eric's contributions

- ^ Wiggin, Kate Douglas Smith (1 April 1999). The Story of Waitstill Baxter – via Project Gutenberg.

Bibliography

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Rutherford, Mildred Lewis (1894). American Authors: A Hand-book of American Literature from Early Colonial to Living Writers. Franklin printing and publishing Company.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Rutherford, Mildred Lewis (1894). American Authors: A Hand-book of American Literature from Early Colonial to Living Writers. Franklin printing and publishing Company.- "Living Authors: Kate Douglas Wiggin". The Intelligence: A Journal of Education: 64–65. January 15, 1900.

External links

Works related to Woman of the Century/Kate Douglas Wiggin at Wikisource

Works related to Woman of the Century/Kate Douglas Wiggin at Wikisource- Works by Kate Douglas Smith Wiggin at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Kate Douglas Wiggin at Internet Archive

- Works by Kate Douglas Wiggin at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Kate Douglas Smith Wiggin at Library of Congress, with 146 library catalog records

- Kate Douglas Wiggin at IMDb

- Bowdoin collection and brief biography

- The Dorcas Society of Hollis & Buxton, Maine

- free online sheet music of Nine Love Songs and a Carol by Kate Douglas Wiggin

- Full text of The Diary of a Goose Girl, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1902.

- Kate Wiggin Papers Dartmouth College Library