Lancelot

| Lancelot | |

|---|---|

| Matter of Britain character | |

| |

| First appearance | Erec and Enide |

| Created by | Possibly Chrétien de Troyes |

| Based on | Uncertain origins |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias | White Knight, Black Knight, Red Knight, Wicked Knight |

| Title | Prince, Sir |

| Occupation | Knight-errant, Knight of the Round Table |

| Weapon | Secace (Seure),[1]

Aroundight Celtic Briton or French |

Lancelot du Lac (French for Lancelot of the Lake), alternatively written as Launcelot and other variants,[a] is a popular character in the Arthurian legend's chivalric romance tradition. He is typically depicted as King Arthur's close companion and one of the greatest Knights of the Round Table, as well as a secret lover of Arthur's wife, Guinevere.

In his most prominent and complete depiction, Lancelot is a beautiful orphaned son of King Ban of the lost kingdom of Benoïc. He is raised in a fairy realm by the Lady of the Lake while unaware of his real parentage prior to joining Arthur's court as a young knight and discovering his origins. A hero of many battles, quests and tournaments, and famed as a nearly unrivalled swordsman and jouster, Lancelot soon becomes the lord of the castle Joyous Gard and personal champion of Queen Guinevere, to whom he is devoted absolutely. He also develops a close relationship with Galehaut and suffers from frequent and sometimes prolonged fits of violent rage and other forms of madness. After Lady Elaine seduces him using magic, their son Galahad, devoid of his father's flaws of character, becomes the perfect knight that succeeds in completing the greatest of all quests, achieving the Holy Grail when Lancelot himself fails due to his sins. Eventually, when Lancelot's adulterous affair with Guinevere is publicly discovered, it develops into a bloody civil war that, once exploited by Mordred, brings an end to Arthur's kingdom.

Lancelot's first datable appearance as main character is found in Chrétien de Troyes' 12th-century French poem Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart, which already centered around his courtly love for Guinevere. However, another early Lancelot poem, Lanzelet, a German translation of an unknown French book, did not feature such a motif and the connections between the both texts and their possible common source are uncertain. Later, his character and story was expanded upon Chrétien's tale in the other works of Arthurian romance, especially through the vast Lancelot-Grail prose cycle that presented the now-familiar version of his legend following its abridged retelling in Le Morte d'Arthur. Both loyal and treasonous, Lancelot has remained a popular character for centuries and is often reimagined by modern authors.

History

Name and origins

There have been many theories regarding the origins of Lancelot as an

Alfred Anscombe proposed in 1913 that the name "Lancelot" came from Germanic *Wlancloth, with roots in the

Lancelot may have been the hero of a popular folk tale that was originally independent but was ultimately absorbed into the Arthurian tradition. The theft of an infant by a water

Stephen Pow has recently argued that the name "Lancelot" represents an Old French pronunciation of Hungarian "

Chrétien and Ulrich

Lancelot's name appears third on a list of knights at King Arthur's court in the earliest known work featuring him as a character: Chrétien de Troyes' Old French poem

It is not until Chrétien's Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart (Le Chevalier de la charrette), however, that he becomes the protagonist and is given the full name Lancelot du Lac (Lancelot of the Lake),[18] which was later picked up by the French authors of the Lancelot-Grail and then by Thomas Malory.[19] Chrétien treats Lancelot as if his audience were already familiar with the character's background, yet most of the characteristics and exploits that are commonly associated with Lancelot today are first mentioned here. The story tells of Lancelot's mad love for Arthur's wife Queen Guinevere, culminating in his rescue of her after she is abducted by Prince Meliagant (also in love for her, but entirely unrequited) to the otherworldly and perilous land of Gorre.

In the words of Matilda Bruckner, "what existed before Chrétien remains uncertain, but there is no doubt that his version became the starting point for all subsequent tales of Lancelot as the knight whose extraordinary prowess is inextricably linked to his love for Arthur's Queen."[20] According to of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, "the character of Lancelot, as imagined by Chrétien, is a superb image of the courtly lover pushing the love he bears for his lady to the point of exaltation and ecstasy ... governed by love, Lancelot no longer knows how to see the world around him, he no longer knows who he is."[21]

On the lyrical model of the astonished lover, paralyzed by his love and losing all his faculties while thinking of his lady, Chrétien makes Lancelot a knight who is entirely taken by his passion for the queen. Overwhelmed by desire, he repeatedly forgets the reality around him. [...] The knight is ready for his lady to suffer the wounds that make him a martyr of love, just as Christ is a martyr of God. The lady here becomes the idol to which the knight worships: Lancelot bows before the bed where the queen awaits him as before an altar, remaining in adoration as before a holy relic in which he places all his faith. The night of love between Lancelot and Guinevere is then evoked as a feast for all the senses, and as an indescribable joy, greater and deeper than that known to all other lovers. But the separation, when day breaks, revives the suffering of the knight who leaves in despair: "The body departs, but the heart remains."[21]

Lancelot's love for Guinevere is entirely absent from another early work, Lanzelet, a Middle High German epic poem by Ulrich von Zatzikhoven dating from the very end of the 12th century (no earlier than 1194). Ulrich asserts that his poem is a translation of an earlier work from a "French book" he had obtained, assuring the reader that "there is nothing left out or added compared to what the French book tells." He describes his source as written by a certain Arnaud Daniel in Provençal dialect and which must have differed markedly in several points from Chrétien's story. In Lanzelet, the abductor of Ginover (Guinevere) is named as King Valerin, whose name, unlike that of Chrétien's Meliagant, does not appear to derive from the Welsh Melwas. Furthermore, Ginover's rescuer is not Lanzelet, who instead ends up finding happiness in marriage with the fairy princess Iblis. The book's Lancelot is Arthur's nephew, the son of Arthur's sister Queen Clarine, who lost his father King Pant of Genewis to a rebellion. Similar to Chrétien's version, Lanzelet too is raised by a fairy. Here she is elaborated as the aquatic Queen of the Maidenland and is the source of much of his early adventures.[22]

The common elements between the two stories indicate that the legend of Lancelot had began as a

Evolution of the legend

Lancelot's character was further developed during the early 13th century in the

Lancelot is often tied to the religiously Christian themes within the genre of Arthurian romance. His quest for Guinevere in Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart is similar to Christ's quest for the human soul.

German romance Diu Crône gives Lancelot aspects of solar deity type hero, making his strength peak during high noon, a characteristic usually associated with Gawain.[32] The Middle Dutch so-called Lancelot Compilation (c. 1320) contains seven Arthurian romances, including a new Lancelot one, folded into the three parts of the cycle. This new formulation of a Lancelot romance in the Netherlands indicates the character's widespread popularity independent of the Lancelot-Grail cycle.[33] In this story, Lanceloet en het Hert met de Witte Voet ("Lancelot and the Hart with the White Foot"), he fights seven lions to get the white foot from a hart (deer) which will allow him to marry a princess.[34] Near the end of the 15th century, Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur followed the Lancelot-Grail in presenting Lancelot as the best knight, a departure from the preceding English tradition in which Gawain had been the most prominent.[35]

The forbidden love affair between Lancelot and Guinevere can be seen as a parallel to that of

Cyclical prose tradition

Birth and childhood

In his backstory, as told in the Vulgate Cycle, Lancelot is born "in the borderland between Gaul and Brittany" as Galahad (originally written Galaad or Galaaz, not to be confused with his own son of the same name), son of the Gallo-Roman ruler King Ban of Bénoïc (English 'Benwick', corresponding to the eastern part of Anjou). Ban's kingdom has just fallen to his enemy, King Claudas, and the mortally wounded king and his wife Queen Élaine flee the destruction of their final stronghold of Trebe or Trébes (likely the historic Trèves Castle in today's Chênehutte-Trèves-Cunault), carrying the infant child with them. As Elaine tends to her dying husband, Lancelot is carried off by a fairy enchantress known as the Lady of the Lake; the surviving Elaine will later become a nun. In an alternate version as retold in the Italian La Tavola Ritonda, Lancelot is born when the late Ban's wife Gostanza delivers him two months early and soon after also dies.

The Lady then raises the child in her magical realm. After three years

An early part of the Vulgate Lancelot also describes in a great detail what made him (in a translation by Norris J. Lacy) "the most handsome lad in the land", noting the feminine qualities of his hands and neck and the just right amount of musculature. Diverging on Lancelot's personality, the narration then adds his proneness to berserk-like combat frenzy to his mental instability already prominent Chrétien's version (where Lancelot is notably relentless on his quest to rescue Guinevere, leaping into danger without thinking and ignoring wounds and pain):

His eyes were bright and smiling and full of delight as long as he was in a good mood, but when he was angry, they looked just like glowing coals and it seemed that drops of red blood stood out from his cheekbones. He would snort like an angry horse and clench and grind his teeth, and it seemed that the breath coming out of his mouth was all red; then he would shout like a trumpet in battle, and whatever he had his teeth in or was gripping in his hands he would pull to pieces. In short, when he was in a rage, he had no sense or awareness of anything else, and this became apparent on many an occasion.[38]

King Arthur's court

Lancelot's initial adventures (also in Malory

Lancelot is eventually convinced[48] to become a member of King Arthur's elite order of the Round Table after freeing the Arthur's nephew Gawain from captivity in the Dolorous Tower episode. He then becomes one of Arthur's closes and most trusted friends, and his greatest knight. As such, he plays a decisive role in the war against the Saxons in Lothian (Scotland), when he again rescues Gawain as well as Arthur himself from Castle Saxon Rock and captures the Saxon witch-princess Camille. Single-handedly, he saves Arthur's kingdom from conquest by the half-giant Galehaut and convinces the latter to join Arthur.

Expanding on the account from the Alliterative Morte Arthure, Malory also has his Lancelot act as one of the chief leaders in Arthur's Roman War, including personally saving the wounded Bedivere during the final battle against Emperor Lucius.[49] Since much of Le Morte was not composed chronologically, the Roman episode actually takes place within Malory's Book II, prior to Book III that relates Lancelot's youth.

Guinevere and knight-errantry

Almost immediately upon his arrival, Lancelot and the young Queen Guinevere fall in love through a strange magical connection between them, and one of his adventures in the prose cycles involves saving her from abduction by Arthur's enemy Maleagant. The exact timing and sequence of events vary from one source to another, and some details are found only in certain sources. The Maleagant episode actually marked the end of the original, non-cyclic version of the Prose Lancelot (before the later much longer versions), telling of only of the hero's childhood and early youth.[51] In the Prose Lancelot, he is actually knighted by Guinevere instead of by Arthur.[52]

In Malory's abridged telling in Le Morte d'Arthur, Lancelot's knighting is performed by the King, and both Lancelot's rescue of the Queen from Meleagant and the physical consummation of their relationship is postponed for years. As described by Malory, after having broken through the iron bars of her prison chamber with his bare hands, "Sir Launcelot wente to bedde with the Quene and toke no force of his hurte honed, but toke his plesaunce and hys lyknge untyll hit was the dawning of the day."

Lancelot dedicates his deeds to his lady Guinevere, acting in her name as her knight. At one point, he goes mad when he is led to believe that Guinevere doubts his love until he is found and healed by the Lady of the Lake.

At one point, Lancelot (up to then still going as just the White Knight) conquers and wins for himself a castle in Britain, known as Joyous Gard (a former Dolorous Gard), where he learns his real name and heritage, taking the name of his illustrious ancestor Lancelot as his own. With the help of King Arthur, Lancelot then defeats Claudas (and his allied Romans in the Vulgate) and recovers his father's kingdom. However, he again decides to remain at Camelot, along with his cousins Bors and Lionel and his illegitimate half-brother Hector de Maris (Ector).

Guinevere's rivals and Galehaut

Lancelot becomes one of the most famous Knights of the Round Table, even attested as the best knight in the world in Malory's own episode of Sir Urry of Hungary, as well as an object of desire by many ladies, beginning with the gigantic Lady of Malehaut when he is her captive early on in the Vulgate Lancelot. An evil sorceress named Hellawes wants him for herself so obsessively that, failing in having him either dead or alive in Malory's chapel perilous episode, she soon herself dies from sorrow. Similarly, Elaine of Astolat (Vulgate's Demoiselle d'Escalot, in modern times better known as "the Lady of Shalott"), also dies of heartbreak due to her unrequited love of Lancelot. On his side, Lancelot falls in a mutual but purely platonic love with an avowed virgin maiden, whom Malory calls Amable (unnamed in the Vulgate).

Lancelot, incognito as the Black Knight[59] (on another occasion he disguises himself as the Red Knight as well),[59][60] plays decisive role in the war against the powerful foreign invader, Prince Galehaut (Galahaut). Galehaut is poised to become the victor and conquer Arthur's kingdom, but he is taken by Lancelot's amazing battlefield performance and offers him a boon in return for the privilege of one night's company in the bivouac. Lancelot accepts and uses his boon to demand that Galehaut surrender peacefully to Arthur. Galehaut then becomes Lancelot's self-proclaimed vassal and the king's ally, later joining the Round Table after Lancelot finally does.[48]

The exact nature of Galehaut's passion for Lancelot is a subject of debate among modern scholars, with some interpreting it as intimate friendship and others as love similar to that between Lancelot and Guinevere.[61] Galehaut is obsessed with having Lancelot all for himself. Publicly submissive to Lancelot by his own choice, he is constantly acting very possessive of him regarding both Guinevere and Arthur, so much that Gawain comments that Galehaut is more jealous of Lancelot than any knight is of his lady.[48] At first, Lancelot goes to live with Galehaut in his home country of Sorelois. Guinevere joins them there after Lancelot saves her from the bewitched Arthur during the "false Guinevere" episode.[62] After that, Arthur invites Galahaut to join the Round Table. Galahaut is also the one who convinces Guinevere that she may return Lancelot's affection.[48] In the Prose Tristan and its adaptations, including the account within the post-Vulgate Queste, Lancelot himself harbors in his castle the fugitive lovers Tristan and Iseult as they flee from the vengeful King Mark of Cornwall.

Faithful to Queen Guinevere, he refuses the forceful advances of Queen Morgan le Fay, Arthur's enchantress sister. Morgan constantly attempts to seduce Lancelot, whom she at once lustfully loves and hates with the same great intensity. She even kidnaps him repeatedly, once with her coven of fellow magical queens including Sebile. On one occasion (as told in the prose Lancelot), Morgan agrees to temporarily release Lancelot to save Gawain, on the condition that Lancelot will return to her immediately afterwards; she then sets him free under the further condition that he not spend any time with either Guinevere or Galehaut for a year. This condition causes Lancelot to go half mad, and Galehaut to fall sick out of longing for him. Galehaut eventually dies of anguish, after he receives a false rumour of Lancelot's suicide.

Elaine, Galahad and the Grail

Princess Elaine of Corbenic, daughter of the Fisher King, also falls in love with him but is more successful than the others. With the help of magic, Lady Elaine tricks Lancelot into believing that she is Guinevere, and thus makes him sleep with her by deception.[63] The ensuing pregnancy results in the birth of his son Galahad, whom Elaine will send off to grow up without a father. Galahad later emerges as the Merlin-prophesied Good Knight, destined for great deeds, who will find the Holy Grail.

But Guinevere learns of their affair, and becomes furious when she finds that Elaine has made Lancelot sleep with her by magic trickery for a second time and in Guinevere's own castle. She blames Lancelot and banishes him from Camelot. Broken by her reaction, Lancelot goes mad again. He flees and vanishes, wandering the wilderness for (either two or five) years. During this time, he is searched for by the remorseful Guinevere and the others. Eventually, he arrives back at

Upon his return to the court of Camelot, Lancelot takes part in the great Grail Quest. The quest is initiated by Lancelot's estranged son, the young teenage Galahad, having prevailed over his father in a duel during his own dramatic arrival at Camelot, among other acts that proved him as the most perfect knight. Following further adventures, during which he experiences defeat and humiliation, Lancelot himself is again allowed only a glimpse of the Grail because he is an

Conflict with Arthur

Ultimately, Lancelot's affair with Guinevere is a destructive force, which was glorified and justified in the Vulgate Lancelot but becomes condemned by the time of the Vulgate Queste.[65] After his failure in the Grail quest, Lancelot tries to live a chaste life, angering Guinevere who sends him away, although they soon reconcile and resume their relationship as it had been before Elaine and Galahad. When Maleagant tries to prove Guinevere's infidelity, he is killed by Lancelot in a trial by combat. Lancelot also saves the Queen from an accusation of murder by poison when he fights as her champion against Mador de la Porte upon his timely return in another episode included in Malory's version. In all, Lancelot fights in five such duels throughout the prose Lancelot.[66]

However, after the truth about Lancelot and Guinevere is finally revealed to Arthur by Morgan, it leads to the death of three of Gawain's brothers (Agravain, Gaheris and Gareth) when Lancelot with his family and followers arrive to violently save the condemned queen from being burned at the stake. During her rescue, the rampaging Lancelot and his companions slaughter the men sent by Arthur to guard the execution, including those who went unwilling and unarmed (as did Lancelot's own close friend Gareth, whose head he crushes in a blind rage). In Malory's version, Agravain is killed by Lancelot earlier, during his bloody escape from Camelot, as well as Florent and Lovel, two of Gawain's sons (Arthur's nephews) who accompanied Agravain and Mordred in their ambush of Lancelot in Guinevere's chambers along with several other knights from Scotland. In the Vulgate Mort Artu, Lancelot's now-vacated former seat at the Round Table is given to an Irish knight named Elians.

The killing of Arthur's loyal knights, including some of the king's own relatives, sets in motion the events leading to the treason by Mordred and the disappearance and apparent death of Arthur. The civil war between Arthur and Lancelot was introduced in the Vulgate Mort Artu, where it replaced the great Roman War taking place at the end of Arthur's reign in the chronicle tradition. What first occurs is a series of engagements waged against Lancelot's faction by Arthur and the vengeful Gawain; they besiege Lancelot at Joyous Gard for two months and then pursue him with their army into Gaul (France in Malory).

The eventual result of this is the betrayal of Arthur by Mordred, the king's bastard son (and formerly one of Lancelot's young followers), who falsely announces Arthur's death to seize the throne for himself. Meanwhile, Gawain challenges Lancelot to a duel twice; each time Lancelot delays because of Gawain's enchantment that makes him grow stronger between morning and noon. Lancelot then strikes down Gawain with Galahad's sword but spares Gawain's life (in the Vulgate, despite being urged by Hector to finish him off[67]). However, Gawain's head wound nevertheless proves to be fatal later, when it reopens during the war with Mordred back in Britain. Upon receiving a desperate letter from the dying Gawain offering him forgiveness and asking for his help in the fight against Mordred, Lancelot hurries to return to Britain with his army, only to hear the news of Arthur's death at Salisbury Plain (romance version of the Battle of Camlann).

Late years and death

There are two main variants of Lancelot's demise, both involving him spending his final years removed from society as a hermit monk. In the original from the variants of Mort Artu, after mourning his king, Lancelot abandons society, with exception of his later participation in a victorious war against the young sons of Mordred and their Briton supporters and Saxon allies that provides him with partial atonement for his earlier role in the story.[68] It happens shortly after the death of Guinevere, as Lancelot personally kills one of Mordred's sons after chasing him through a forest in the battle at Winchester, but himself goes abruptly missing. Lancelot dies of illness four years later, accompanied only by Hector, Bleoberis, and the former archbishop of Canterbury. It is implied that he wished to be buried beside the king and queen, however, he had made a vow some time before to be buried at Joyous Gard next to Galehaut, so he asks to be buried there to keep his word. In the Post-Vulgate, the burial site and bodies of Lancelot and Galehaut are later destroyed by King Mark when he ravages Arthur's former kingdom.

There is no war with the sons of Mordred in the version included in Le Morte d'Arthur.

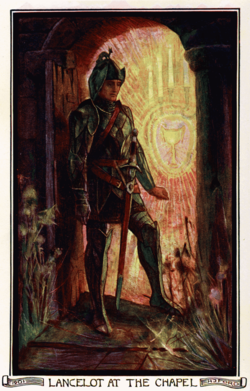

Gallery

-

"How Lancelot fought the six knights of Chastel d'Uter to save theTristan en prosec. 1479–1480)

-

Lancelot, dressed in brown, living with his companions in a hermit hut at the end of his life (Tristan en prose c. 1450–1460)

- N. C. Wyeth's illustrations from The Boy's King Arthur

-

Facing Turquine: "I am Sir Launcelot du Lake, King Ban's son of Benwick."

-

"Sir Mador's spear broke all to pieces, but his spear held."

-

"[Lancelot] ever ran wild wood from place to place"

-

"Launcelot saw her visage, he wept not greatly, but sighed."

Modern culture

Lancelot appeared as a character in many Arthurian films and television productions, sometimes even as the protagonistic titular character. He has been played by

- T. H. White's novel The Once and Future King (1958) portrays Lancelot very differently from his usual image in the legend. Here, Lancelot is immensely ugly and introverted, having difficulty dealing with people.

- Lancelot is played by stage musical adaptation of the film. Lancelot was played by Hank Azaria in the original Broadway production. In this version, Lancelot is gay and marries Prince Herbert (portrayed by Christian Borlein the original Broadway production).

- In a 1986 episode of The Twilight Zonebased on the story.

- In film adaptation(2001).

- Lancelot is a major character in Derfel(who had lost his daughter to Lancelot's scheming). Lancelot's glowing depictions in legends are explained as merely an influence of the stories invented by the bards hired by his mother.

- A character based on him named Sir Loungelot is one of the main characters in the animated series Blazing Dragons (1996), but being adapted as a fat, arrogant and cowardly dragon who is the leader of the Knights of Camelhot.

- Lancelot is a recurring character in The Squire's Tales series (1998–2010) by Gerald Morris. In some books he is a major character and in others is a secondary character. This version of Lancelot is initially presented as a talented knight, but somewhat pompous and vain. In later books, filled with regret over his affair with Guinevere, he renounces court and is presented as more humble and wise. He leaves court to become a woodcutter, though he is occasionally swept up in quests to help Arthur and other knights.

- The video game Age of Empires II: The Age of Kings (1999) features Lancelot as a paladin.

- The 2003 novel Arthur Pendragon.

- Lancelot is played by Battle of Badon Hill.

- Thomas Cousseau played Lancelot du Lac in the French comedy TV series Kaamelott (2005–2009), in which he is portrayed as the only competent Knight of the Round Table and a classically chivalrous hero unlike all the others, however still ill-fated.[73]

- Jason Griffith portrayed him in the video game Sonic and the Black Knight (2009). Lancelot's appearance is based on Shadow the Hedgehog.

- Lancelot appears in the light novel and its 2011 anime adaptation Kyle Herbert. Lancelot also appears in the mobile game Fate/Grand Orderas a Berserker but also as a Saber class Servant.

- Lancelot is a character in the romance novel Knight Fantasy Night (骑士幻想夜, Qishi Huanxiang Ye) by Vivibear (2013), adapted into a comic book in Samanhua (飒漫画).

- Sophie Cookson's character Roxanne "Roxy" Morton in the film Kingsman: The Secret Service (2014) and its sequel uses the code name Lancelot. It was also used by Aaron Taylor-Johnson's character Archie Reid in the prequel.

- Lancelot is the primary antagonist in the first season of The Librarians (2014), portrayed by both Matt Frewer and Jerry O'Connell. He gained immortality sometime after the fall of Camelot through magic and has spent centuries seeking to reverse the events that brought about its destruction. As the mysterious Dulaque (a respelling of his name du Lac), he leads the Serpent Brotherhood, a cult that has long opposed the Library's mission to keep magic out of the hands of humans.

- In the video game Mobile Legends: Bang Bang (2016), Lancelot is a playable character portrayed as Guinevere's brother.

- Giles Kristian's novel Lancelot (2018) is an original telling of the Lancelot story.

- The immortal Lancelot Du Lac, voiced by Du Lac & Fey: Dance of Death(2019), an adventure video game set in Victorian London.

- In the illustrated novel Cursed (2019) by Frank Miller and Tom Wheeler Lancelot is a violent Christian fanatic known as "The Weeping Monk". In the Netflix adaptation of Cursed (2020), he is played by Daniel Sharman.

- Lancelot is the major character in the animated series Wizards: Tales of Arcadia (2020), voiced by Rupert Penry-Jones.

- Lancelot is featured in the video game Smite as a horseback assassin armed with a lance.

- Lancelot is one of the titular knights in the manga series Four Knights of the Apocalypse. He is the son of Ban and Elaine.

- Lancelot is a primary antagonist of Lev Grossman's 2024 novel The Bright Sword, where he is the greatest swordsman in Britain, and seizes the throne after Arthur's death under the name Galahad (his illegitimate son).

Notes

- ^ Such as early German Lanzelet, early French Lanselos, early Welsh Lanslod Lak, Italian Lancillotto, Spanish Lanzarote del Lago, and Welsh Lawnslot y Llyn.

References

- ISBN 9781476639208– via Google Books.

- ^ Ellis, George, ed. (1805). "Sir Bevis of Hamptoun". Specimens of early English metrical romances. Vol. 2. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, & Orme. pp. 165–166.

- ^ a b Bruce, The Arthurian Name Dictionary, pp. 305–306.

- ISBN 9780761822189– via Google Books.

- ISBN 978-0-8153-3566-5. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-134-37202-7. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Alfred Anscombe (1913), "The Name of Sir Lancelot du Lake", The Celtic Review 8(32): 365–366.

- ^ Alfred Anscombe (1913), "Sir Lancelot du Lake and Vinovia", The Celtic Review 9(33): 77–80.

- ^ ISBN 9780761822189– via Google Books.

- ^ International Arthurian Society (1981). Bulletin bibliographique de la Société internationale arthurienne (in French). p. 1–PA192. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-4721-0113-6. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ISBN 9781910705407– via Google Books.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Weston, Jessie Laidlay (1911). "Lancelot". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 151.

- ^ Frédéric Godefroy, Dictionnaire de l’ancienne langue française et de tous ses dialectes du IXe au XVe siècle, édition de F. Vieweg, Paris, 1881–1902, p. 709b.

- ISSN 0999-6001.

- ISBN 9780715352014– via Google Books.

- ^ Stephen Pow, "Evolving Identities: A Connection between Royal Patronage of Dynastic Saints' Cults and Arthurian Literature in the Twelfth Century", Annual of Medieval Studies at CEU (2018): 65–74.

- ^ William Farina, Chretien de Troyes and the Dawn of Arthurian Romance (2010). p. 13: "Strictly speaking, the name Lancelot du Lac ("Lancelot of the Lake") first appears in Chrétien's Arthurian debut, Erec and Enide (line 1674), as a member of the Roundtable."

- ^ Elizabeth Archibald, Anthony Stockwell Garfield Edwards, A Companion to Malory (1996). p. 170: "This is the book of my lord Lancelot du Lac in which all his deeds and chivalric conduct are contained and the coming of the Holy Grail and his quest (which was) made and achieved by the good knight, Galahad."

- JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt9qdj80.15.

- ^ a b "Lancelot et les excès de l'amour". BnF Essentiels.

- ISBN 0-8240-4377-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84384-396-2.

- S2CID 162124722.

- ISBN 0 19 811588 1pp. 436–439 in Essay 33 Hartmann von Aue and his Successors by Hendricus Spaarnay.

- ISBN 978-1-84384-316-0.

- ISBN 9781118234303– via Google Books.

- ^ Raabe, Pamela (1987). Chretien's Lancelot and the Sublimity of Adultery. Toronto Quarterly. 57: 259–270.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-86611-982-5.

- ^ Joe, Jimmy. "Grail Legends (Perceval's Tradition)". timelessmyths.com. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-85991-783-4– via Google Books.

- ISBN 9781613732106.

- ISBN 978-0851153810.

- ^ "Lanceloet en het hert met de witte voet auteur onbekend, vóór 1291, Brabant". www.literatuurgeschiedenis.org (in Dutch). Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ Radulescu, R. (2004). "‘Now I take uppon me the adventures to seke of holy thynges’: Lancelot and the Crisis of Arthurian Knighthood." In B. Wheeler (Ed.), Arthurian Studies in Honour of P.J.C. Field (pp. 285–296). Boydell & Brewer.

- ^ MacBain, Danielle Morgan (1993). The Tristramization of Malory's Lancelot. English Studies. 74: 57–66.

- ISBN 978-1-84384-104-3.

- ^ ISBN 9781843842262.

- ^ Lacy, Norris J. (Ed.) (1995). Lancelot–Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation, Volume 3 of 5. New York: Garland.

- ISBN 9781843842330– via Google Books.

- ISBN 978-0-85991-443-7.

- ISBN 978-1-317-72155-0.

- ISBN 978-0-19-283793-6.

- ISBN 9781843841715.

- ISBN 9780292786400.

- ISBN 9781843842354.

- ^ "Highlights in the Story". www.lancelot-project.pitt.edu. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ ISBN 90-04-10018-0– via Google Books.

- ISBN 9781421433110.

- ISBN 978-1-84384-068-8.

- ISBN 9781846158063.

- ISBN 978-0-85991-603-5.

- ISBN 9780859915205.

- ^ Norris, Ralph C. (27 April 2008). "Malory's Library: The Sources of the Morte Darthur". DS Brewer – via Google Books.

- ^ "La légende du roi Arthur". BnF – expositions.bnf.fr (in French). Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- S2CID 161934474.

- S2CID 161443290.

- ISBN 9781843842354.

- ^ a b Bruce, ___. The Arthurian Name Dictionary. p. 200.

- ISBN 9781843842521.

- ISBN 9780874130249– via Google Books.

- ^ "Will the real Guinevere please stand up?". Medievalists.net. 17 December 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-7867-1566-4.

- ^ "Malory's Sangrail". web.stanford.edu.

- ^ Dover, A Companion to the Lancelot-Grail Cycle, p. 119.

- JSTOR soutatlarevi.81.2.55.

- ISBN 9781317656913.

- ^ Dover, A Companion to the Lancelot-Grail Cycle, pp. 121–122.

- ISBN 978-0-313-29798-4.

- JSTOR 27870787.

- ISBN 978-2-87775-888-8– via Google Books.

- ^ "The Tale of Sir Lancelot". Creative Analytics. 16 November 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- S2CID 166482886.

Bibliography

- Bruce, Christopher W. (1998). The Arthurian Name Dictionary. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8153-2865-0.

- Dover, Carol (2003). A Companion to the Lancelot-Grail Cycle. D.S. Brewer. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-85991-783-4.

- Kennedy, E. "Introduction". Lancelot of the Lake. Oxford World's Classics. Translated by Corley, Corin. Oxford University Press.

External links

- Lancelot at The Camelot Project

- An English translation of the Prose Lancelot at the Internet Archive

- Lancelot digital exposition at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (in French)

!["[Lancelot] ever ran wild wood from place to place"](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cb/Boys_King_Arthur_-_N._C._Wyeth_-_p52.jpg/330px-Boys_King_Arthur_-_N._C._Wyeth_-_p52.jpg)