Light effects on circadian rhythm

Light effects on circadian rhythm are the effects that light has on circadian rhythm.

Most animals and other organisms have "built-in clocks" in their brains that regulate the timing of

Mechanism

Light first passes into a mammal's system through the

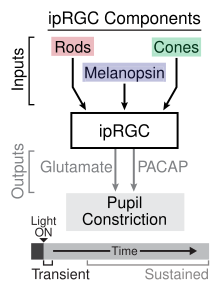

The RGCs use the photopigment

The ipRGCs serve a different function than rods and cones, even when isolated from the other components of the retina, ipRGCs maintain their

The core region of the SCN houses the majority of light-sensitive neurons.[12] From here, signals are transmitted via a nerve connection with the pineal gland which regulates various hormones in the human body.[13]

There are specific

Some important structures directly impacted by the light-sleep relationship are the superior colliculus-pretectal area and the ventrolateral pre-optic nucleus.[10][9]

The progressive yellowing of the

Effects

Primary

All of the mechanisms of light-affected entrainment are not yet fully known, however numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of light entrainment to the day/night cycle. Studies have shown that the timing of exposure to light influences entrainment; as seen on the phase response curve for light for a given species. In diurnal (day-active) species, exposure to light soon after wakening advances the circadian rhythm, whereas exposure before sleeping delays the rhythm.[5][15][12] An advance means that the individual will tend to wake up earlier on the following day(s). A delay, caused by light exposure before sleeping, means that the individual will tend to wake up later on the following day(s).

The hormones cortisol and melatonin are affected by the signals light sends through the body's nervous system. These hormones help regulate blood sugar to give the body the appropriate amount of energy that is required throughout the day. Cortisol levels are high upon waking and gradually decrease over the course of the day, melatonin levels are high when the body is entering and exiting a sleeping status and are very low over the course of waking hours.[13] The earth's natural light-dark cycle is the basis for the release of these hormones.

The length of light exposure influences entrainment. Longer exposures have a greater effect than shorter exposures.[15] Consistent light exposure has a greater effect than intermittent exposure.[3] In rats, constant light eventually disrupts the cycle to the point that memory and stress coping may be impaired.[16]

The intensity and the wavelength of light influence entrainment.[6] Dim light can affect entrainment relative to darkness.[17] Brighter light is more effective than dim light.[15] In humans, a lower intensity short wavelength (blue/violet) light appears to be equally effective as a higher intensity of white light.[5]

Exposure to

In a study done on the effect of lighting intensity on

Humans are sensitive to light with a short wavelength. Specifically, melanopsin is sensitive to blue light with a wavelength of approximately 480 nanometers.[20] The effect this wavelength of light has on melanopsin leads to physiological responses such as the suppression of melatonin production, increased alertness, and alterations to the circadian rhythm.[20]

Secondary

While light has direct effects on circadian rhythm, there are indirect effects seen across studies.[8] Seasonal affective disorder creates a model in which decreased day length during autumn and winter increases depressive symptoms.[10][8] A shift in the circadian phase response curve creates a connection between the amount of light in a day (day length) and depressive symptoms in this disorder.[10][8] Light seems to have therapeutic antidepressant effects when an organism is exposed to it at appropriate times during the circadian rhythm, regulating the sleep-wake cycle.[10][8]

In addition to mood, learning and memory become impaired when the circadian system shifts due to light stimuli,[10][21] which can be seen in studies modeling jet lag and shift work situations.[8] Frontal and parietal lobe areas involved in working memory have been implicated in melanopsin responses to light information.[21]

"In 2007, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified shift work with circadian disruption or chronodisruption as a probable human carcinogen."[22]

Exposure to light during the hours of melatonin production reduces melatonin production. Melatonin has been shown to mitigate the growth of tumors in rats. By suppressing the production of melatonin over the course of the night rats showed increased rates of tumors over the course of a four-week period.[23]

Artificial light at night causing circadian disruption additionally impacts sex steroid production. Increased levels of progestogens and androgens was found in night shift workers as compared to "working hour" workers.[22]

The proper exposure to light has become an accepted way to alleviate some of the effects of seasonal affective disorder (SAD). In addition exposure to light in the morning has been shown to assist Alzheimer patients in regulating their waking patterns.[24]

In response to light exposure, alertness levels can increase as a result of suppression of melatonin secretion.

Disruption of circadian rhythm as a result of light also produces changes in metabolism.[8]

Measured lighting for rating systems

Historically light was measured in the units of luminous intensity (

The accepted current unit is equivalent melanopic lux which is a calculated ratio multiplied by the unit lux. The melanopic ratio is determined taking into account the source type of light and the melanopic illuminance values for the eye's photopigments.[26] The source of light, the unit used to measure illuminance and the value of illuminance informs the spectral power distribution. This is used to calculate the Photopic illuminance and the melanopic lux for the five photopigments of the human eye, which is weighted based on the optical density of each photopigment.[26]

The WELL Building standard was designed for "advancing health and well-being in buildings globally"[27] Part of the standard is the implementation of Credit 54: Circadian Lighting Design. Specific thresholds for different office areas are designated in order to achieve credits. Light is measured at 1.2 meters above the finished floor for all areas.

Work areas must have at least a value of 200 equivalent melanopic lux present for 75% or more work stations between the hours of 9:00 A.M. and 1:00 P.M. for each day of the year when daylight is incorporated into calculations. If daylight is not taken into account all workstations require lighting at the value of 150 equivalent melanopic lux or greater.[28]

Living environments, which are bedrooms, bathrooms and rooms with windows, at least one fixture must provide a melanopic lux value of at least 200 during the day and a melanopic lux value less than 50 during the night, measured .76 meters above the finished floor.[28]

Breakrooms require an average melanopic lux of 250.[28]

Learning areas require either that light models which may incorporate daylighting have an equivalent melanopic lux of 125 at at least 75% of desks for at least four hours per day or ambient lights maintain the standard lux recommendations set forth by Table 3 of the IES-ANSI RP-3-13.[28]

The WELL Building standard additionally provides direction for circadian emulation in multi-family residences. In order to more accurately replicate natural cycles lighting users must be able to set a wake and bed time. An equivalent melanopic lux of 250 must be maintained in the period of the day between the indicated wake time and two hours before the indicated bed time. An equivalent melanopic lux of 50 or less is required for the period of the day spanning from two hours before the indicated bed time through the wake time. In addition at the indicated wake time melanopic lux should increase from 0 to 250 over the course of at least 15 minutes.[29]

Other factors

Although many researchers consider light to be the strongest cue for entrainment, it is not the only factor acting on circadian rhythms. Other factors may enhance or decrease the effectiveness of entrainment. For instance, exercise and other physical activity, when coupled with light exposure, results in a somewhat stronger entrainment response.

Circadian-based effects have also been found on visual perception to discomfort glare.[33] The time of day is which people are shown a light source that produces visual discomfort is not perceived evenly. As the day progress, people tend to become more tolerant to the same levels of discomfort glare (i.e., people are more sensitive to discomfort glare in the morning compared to later in the day.) Further studies on chronotype show that early chronotypes can also tolerate more discomfort glare in the morning compared to late chronotypes.[34]

See also

- Chronobiology

- Circadian advantage

- Circadian clock

- Circadian oscillator

- Circadian rhythm disorders

- Electronic media and sleep

- Light therapy

- Scotobiology

References

- S2CID 10799409.

- PMID 10381883.

- ^ PMID 10600904.

- PMID 17898172.

- ^ S2CID 913608.

- ^ PMID 20161220.

- ^ S2CID 41456654.

- ^ PMID 24917305.

- ^ PMID 19547745.

- ^ PMID 22244990.

- ^ PMID 24287308.

- ^ S2CID 8653740.

- ^ PMID 16756935.

- PMID 31534436.

- ^ PMID 8866371.

- S2CID 46433973.

- S2CID 35736954.

- PMID 15585546.

- S2CID 143924924.

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 17404390.

- ^ PMID 29458781.

- PMID 12163849.

- S2CID 4015259.

- PMID 16920622.

- ^ a b Lucas R (October 2013). "Irradiance Toolbox" (PDF). personalpages.manchester.ac.uk.

- ^ "International WELL Building Institute". International WELL Building Institute. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- ^ a b c d "Circadian lighting design". WELL Standard. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- ^ "Circadian emulation | WELL Standard". standard.wellcertified.com. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- PMID 16614052.

- PMID 16263827.

- ^ Salazar-Juarez A, Parra-Gamez L, Barbosa Mendez S, Leff P, Anton B (May 2007). "Non-photic entrainment. Another type of entrainment? Part one". Salud Mental. 30 (3): 39–47.

- .

- .