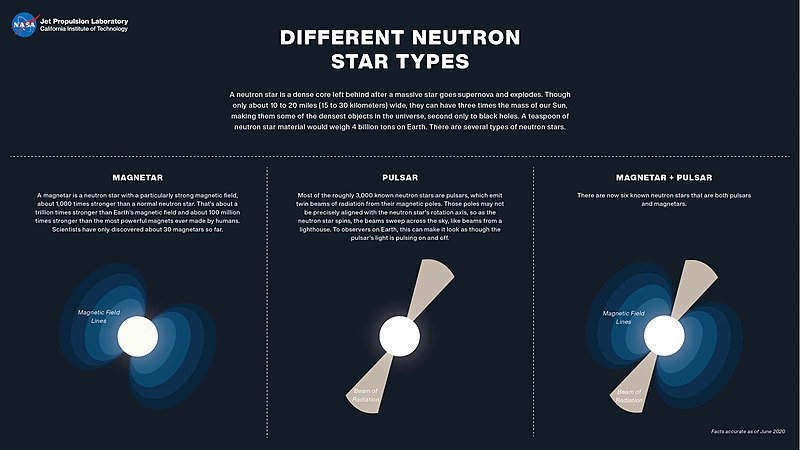

Magnetar

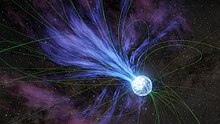

A magnetar is a type of neutron star with an extremely powerful magnetic field (~109 to 1011 T, ~1013 to 1015 G).[1] The magnetic-field decay powers the emission of high-energy electromagnetic radiation, particularly X-rays and gamma rays.[2]

The existence of magnetars was proposed in 1992 by

It has been suggested that magnetars are the source of fast radio bursts (FRB), in particular as a result of findings in 2020 by scientists using the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) radio telescope.[7]

Description

Like other neutron stars, magnetars are around 20 kilometres (12 mi) in diameter, and have a mass of about 1.4 solar masses. They are formed by the collapse of a star with a mass 10–25 times that of the Sun. The density of the interior of a magnetar is such that a tablespoon of its substance would have a mass of over 100 million tons.[2] Magnetars are differentiated from other neutron stars by having even stronger magnetic fields, and by rotating more slowly in comparison. Most observed magnetars rotate once every two to ten seconds,[8] whereas typical neutron stars, observed as radio pulsars, rotate one to ten times per second.[9] A magnetar's magnetic field gives rise to very strong and characteristic bursts of X-rays and gamma rays. The active life of a magnetar is short compared to other celestial bodies. Their strong magnetic fields decay after about 10,000 years, after which activity and strong X-ray emission cease. Given the number of magnetars observable today, one estimate puts the number of inactive magnetars in the Milky Way at 30 million or more.[8]

Starquakes triggered on the surface of the magnetar disturb the magnetic field which encompasses it, often leading to extremely powerful gamma-ray flare emissions which have been recorded on Earth in 1979, 1998 and 2004.[10]

Magnetic field

Magnetars are characterized by their extremely powerful magnetic fields of ~109 to 1011

As described in the February 2003

Origins of magnetic fields

The dominant model of the strong fields of magnetars is that it results from a

Formation

In a supernova, a star collapses to a neutron star, and its magnetic field increases dramatically in strength through conservation of magnetic flux. Halving a linear dimension increases the magnetic field strength fourfold. Duncan and Thompson calculated that when the spin, temperature and magnetic field of a newly formed neutron star falls into the right ranges, a dynamo mechanism could act, converting heat and rotational energy into magnetic energy and increasing the magnetic field, normally an already enormous 108 teslas, to more than 1011 teslas (or 1015 gauss). The result is a magnetar.[19] It is estimated that about one in ten supernova explosions results in a magnetar rather than a more standard neutron star or pulsar.[20]

1979 discovery

On March 5, 1979, a few months after the successful dropping of Landers into the atmosphere of Venus, the two uncrewed Soviet spaceprobes Venera 11 and 12, then in heliocentric orbit, were hit by a blast of gamma radiation at approximately 10:51 EST. This contact raised the radiation readings on both the probes from a normal 100 counts per second to over 200,000 counts a second in only a fraction of a millisecond.[4]

Eleven seconds later,

This was the strongest wave of extra-solar gamma rays ever detected at over 100 times as intense as any previously known burst. Given the

Recent discoveries

On February 21, 2008, it was announced that NASA and researchers at

In April 2020, a possible link between fast radio bursts (FRBs) and magnetars was suggested, based on observations of SGR 1935+2154, a likely magnetar located in the Milky Way galaxy.[27][28][29][30][31]

Known magnetars

As of July 2021[update], 24 magnetars are known, with six more candidates awaiting confirmation.[6] A full listing is given in the McGill SGR/AXP Online Catalog.[6] Examples of known magnetars include:

- SGR 0525−66, in the Large Magellanic Cloud, located about 163,000 light-years from Earth, the first found (in 1979)

- SGR 1806−20, located 50,000 light-years from Earth on the far side of the Milky Way in the constellation of Sagittarius and the most magnetized object known.

- RXTE. On May 29, 2008, NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope discovered a ring of matter around this magnetar. It is thought that this ring formed in the 1998 burst.[32]

- SGR 0501+4516 was discovered on 22 August 2008.[33]

- 1E 1048.1−5937, located 9,000 light-years away in the constellation Carina. The original star, from which the magnetar formed, had a mass 30 to 40 times that of the Sun.

- As of September 2008[update], ESO reports identification of an object which it has initially identified as a magnetar, SWIFT J195509+261406, originally identified by a gamma-ray burst (GRB 070610).[24]

- CXO J164710.2-455216, located in the massive galactic cluster Westerlund 1, which formed from a star with a mass in excess of 40 solar masses.[34][35][36]

- SWIFT J1822.3 Star-1606 discovered on 14 July 2011 by Italian and Spanish researchers of CSIC at Madrid and Catalonia. This magnetar contrary to previsions has a low external magnetic field, and it might be as young as half a million years.[37]

- 3XMM J185246.6+003317, discovered by international team of astronomers, looking at data from ESA's XMM-Newton X-ray telescope.[38]

- SGR 1935+2154, emitted a pair of luminous radio bursts on 28 April 2020. There was speculation that these may be galactic examples of fast radio bursts.

| Magnetar— SGR J1745-2900

|

|---|

Magnetar found very close to the supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A*, at the center of the Milky Way galaxy

|

Bright supernovae

Unusually bright supernovae are thought to result from the death of very large stars as pair-instability supernovae (or pulsational pair-instability supernovae). However, recent research by astronomers[41][42] has postulated that energy released from newly formed magnetars into the surrounding supernova remnants may be responsible for some of the brightest supernovae, such as SN 2005ap and SN 2008es.[43][44][45]

See also

References

- Specific

- .

- ^ a b Ward; Brownlee, p.286

- doi:10.1086/186413.

- ^ a b c d e Kouveliotou, C.; Duncan, R. C.; Thompson, C. (February 2003). "Magnetars". Scientific American; Page 41.

- .

- ^ a b c d "McGill SGR/AXP Online Catalog". Retrieved 26 Jan 2021.

- ^ Starr, Michelle (1 June 2020). "Astronomers Just Narrowed Down The Source of Those Powerful Radio Signals From Space". ScienceAlert.com. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ a b

Kaspi, V. M. (April 2010). "Grand unification of neutron stars". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (16). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America: 7147–7152. PMID 20404205.

- ^ Condon, J. J. & Ransom, S. M. "Pulsar Properties (Essential radio Astronomy)". National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 26 Feb 2021.

- ^ a b c Kouveliotou, C.; Duncan, R. C.; Thompson, C. (February 2003). "Magnetars Archived 2007-06-11 at the Wayback Machine". Scientific American; Page 36.

- ^ "HLD user program, at Dresden High Magnetic Field Laboratory". Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ Naeye, Robert (February 18, 2005). "The Brightest Blast". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Duncan, Robert. "'MAGNETARS', SOFT GAMMA REPEATERS & VERY STRONG MAGNETIC FIELDS". University of Texas.

- ^ Wanjek, Christopher (February 18, 2005). "Cosmic Explosion Among the Brightest in Recorded History". NASA. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ^ Dooling, Dave (May 20, 1998). ""Magnetar" discovery solves 19-year-old mystery". Science@NASA Headline News. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- doi:10.1086/172580– via NASA Astrophysics Data System.

- S2CID 201252025.

- ^ Kouveliotou, p.237

- S2CID 14930432.

- ^ "Biggest Explosions in the Universe Powered by Strongest Magnets". Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ^ Shainblum, Mark (21 February 2008). "Jekyll-Hyde neutron star discovered by researchers]". McGill University.

- ^ a b "The Hibernating Stellar Magnet: First Optically Active Magnetar-Candidate Discovered". ESO. 23 September 2008.

- ^ "Magnetar discovered close to supernova remnant Kesteven 79". ESA/XMM-Newton/ Ping Zhou, Nanjing University, China. 1 September 2014.

- S2CID 119216166.

- ^ Timmer, John (4 November 2020). "We finally know what has been making fast radio bursts - Magnetars, a type of neutron star, can produce the previously enigmatic bursts". Ars Technica. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ Cofield, Calla; Andreoli, Calire; Reddy, Francis (4 November 2020). "NASA Missions Help Pinpoint the Source of a Unique X-ray, Radio Burst". NASA. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- S2CID 218763435. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ^ Drake, Nadia (5 May 2020). "'Magnetic Star' Radio Waves Could Solve the Mystery of Fast Radio Bursts - The surprise detection of a radio burst from a neutron star in our galaxy might reveal the origin of a bigger cosmological phenomenon". Scientific American. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ Starr, Michelle (1 May 2020). "Exclusive: We Might Have First-Ever Detection of a Fast Radio Burst in Our Own Galaxy". ScienceAlert.com. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ "Strange Ring Found Around Dead Star". Archived from the original on 2012-07-21.

- ^ "NASA - European Satellites Probe a New Magnetar". www.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Chandra :: Photo Album :: Westerlund 1 :: 02 Nov 05". chandra.harvard.edu.

- ^ "Magnetar Formation Mystery Solved?". www.eso.org.

- ^ Wood, Chris. "Very Large Telescope solves magnetar mystery" GizMag, 14 May 2014. Accessed: 18 May 2014.

- ^ A new low-B magnetar

- S2CID 118736623.

- ^ "A Cosmic Baby Is Discovered, and It's Brilliant". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

- Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (8 January 2021). "Chandra observations reveal extraordinary magnetar". Phys.org. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- S2CID 118630165.

- S2CID 118564100.

- S2CID 13122542.

- Queen's University, Belfast (16 October 2013). "New light on star death: Super-luminous supernovae may be powered by magnetars". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- S2CID 4472977.

- Books and literature

- ISBN 0-387-98701-0.

- Kouveliotou, Chryssa (2001). The Neutron Star-Black Hole Connection. Springer. ISBN 1-4020-0205-X.

- Mereghetti, S. (2008). "The strongest cosmic magnets: soft gamma-ray repeaters and anomalous X-ray pulsars". Astronomy and Astrophysics Review. 15 (4): 225–287. S2CID 14595222.

- General

- Schirber, Michael (2 February 2005). "Origin of magnetars". CNN.

- Naeye, Robert (18 February 2005). "The Brightest Blast". Sky and Telescope.

External links

- McGill Online Magnetar Catalog McGill Online Magnetar Catalog -- Main Table