Maneless lion

The term "maneless lion" or "scanty mane lion" often refers to a male lion without a mane, or with a weak one.[1][2]

The purpose of the mane is thought to signal the fitness of males to females. Experts disagree as to whether or not the mane defends the male lion's throat in confrontations.[3][4][5][6]

Although lions are known for their mane, not all males have one.[2] This might be because of a polymorphism within males.[7]

Modern lions

In Eurasia

The

In

Lions with such smaller manes were also known in the

In Africa

In

Tsavo is a region of Kenya located at the crossing of the Uganda Railway over the Tsavo River, close to where it meets the Athi-Galana-Sabaki River. Tsavo male lions generally do not have a mane, though colouration and thickness vary. There are several hypotheses as to the reasons. One is that mane development is closely tied to climate because its presence significantly reduces heat loss.[14] An alternative explanation is that manelessness is an adaptation to the thorny vegetation of the Tsavo area in which a mane might hinder hunting. Tsavo males may have heightened levels of testosterone, which could also explain their reputation for aggression.[14]

-

ATsavo lion killed by Patterson

-

Male East African lion with a scanty mane at Samburu National Reserve, Kenya

-

West African lion in Pendjari National Park, Benin

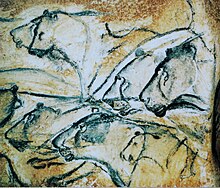

Prehistoric lions

See also

References

- ^ a b Joubert, D. (1996). "Letters: By any other mane". New Scientist: 8. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ a b "What is a maneless lion?". "Dictionary" by Farlex.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ISBN 978-0-0021-6124-4.

- ^ Joubert, D. (18 May 1996), Letters: By any other mane", New Scientist

- S2CID 15893512.

- ISBN 978-0-691-21529-7.

- )

- ^ Sevruguin, A. (1880). "Men with live lion". National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden, The Netherlands; Stephen Arpee Collection. Archived from the original on 26 March 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1939). "Panthera leo". The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. – Volume 1. London: Taylor and Francis Ltd. pp. 212–222.

- ^ Ashrafian, Hutan (2011). "An Extinct Mesopotamian Lion Subspecies". Veterinary Heritage. 34 (2): 47–49.

- ISBN 978-90-04-08876-4.

- ISBN 978-90-04-08876-4.

- S2CID 24190889.

- ^ a b Call the Hair Club for Lions. The Field Museum.

- ^ Schoe, M.; Sogbohossou, E. A.; Kaandorp, J.; De Iongh, H. (2010), "Progress Report – collaring operation Pendjari Lion Project, Benin", The Dutch Zoo Conservation Fund (for funding the project)

- ^ Trivedi, Bijal P. (2005). "Are Maneless Tsavo Lions Prone to Male Pattern Baldness?". The National Geographic. Archived from the original on 5 June 2002. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- ^ Nagel, D.; Hilsberg, S.; Benesch, A.; Scholtz, J. (2003). "Functional morphology and fur patterns in recent and fossil Panthera species". Scripta Geologica 126: 227–239.

- ^ a b "Lions of Ancient Egypt". The American University in Cairo Press.

- ^ Chauvet, J.-M.; Brunel, D. E.; Hillaire, C. (1996). Dawn of Art: The Chauvet Cave. The oldest known paintings in the world. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- ISBN 978-3-8062-1734-6.

- .