Testosterone

This article needs more primary sources. (September 2023) |  |

| |

| |

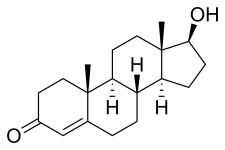

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

17β-Hydroxyandrost-4-en-3-one

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(1S,3aS,3bR,9aR,9bS,11aS)-1-Hydroxy-9a,11a-dimethyl-1,2,3,3a,3b,4,5,8,9,9a,9b,10,11,11a-tetradecahydro-7H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-7-one | |

| Other names

Androst-4-en-17β-ol-3-one

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (

JSmol ) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

ECHA InfoCard

|

100.000.336 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C19H28O2 | |

| Molar mass | 288.431 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 151.0 °C (303.8 °F; 424.1 K)[1] |

| Pharmacology | |

| G03BA03 (WHO) | |

| License data | |

esters), subcutaneous pellets

| |

| Pharmacokinetics: | |

| Oral: very low (due to extensive first pass metabolism) | |

| 97.0–99.5% (to SHBG and albumin)[2] | |

conjugation )

| |

| 30–45 minutes[citation needed] | |

| Urine (90%), feces (6%) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Testosterone is the primary male

Excessive levels of testosterone in men may be associated with

Testosterone is a

In addition to its role as a natural hormone, testosterone is used as a

Biological effects

Effects on physiological development

In general,

- Anabolic effects include growth of bone maturation.

- Androgenic effects include secondary sex characteristics.

Testosterone effects can also be classified by the age of usual occurrence. For

Before birth

Effects before birth are divided into two categories, classified in relation to the stages of development.

The first period occurs between 4 and 6 weeks of the gestation. Examples include genital virilisation such as midline fusion,

During the second trimester, androgen level is associated with sex formation.[21] Specifically, testosterone, along with anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) promote growth of the Wolffian duct and degeneration of the Müllerian duct respectively.[22] This period affects the femininization or masculinization of the fetus and can be a better predictor of feminine or masculine behaviours such as sex typed behaviour than an adult's own levels. Prenatal androgens apparently influence interests and engagement in gendered activities and have moderate effects on spatial abilities.[23] Among women with congenital adrenal hyperplasia, a male-typical play in childhood correlated with reduced satisfaction with the female gender and reduced heterosexual interest in adulthood.[24]

Early infancy

Early infancy androgen effects are the least understood. In the first weeks of life for male infants, testosterone levels rise. The levels remain in a pubertal range for a few months, but usually reach the barely detectable levels of childhood by 4–7 months of age.

Before puberty

Before puberty, effects of rising androgen levels occur in both boys and girls. These include adult-type

Pubertal

Pubertal effects begin to occur when androgen has been higher than normal adult female levels for months or years. In males, these are usual late pubertal effects, and occur in women after prolonged periods of heightened levels of free testosterone in the blood. The effects include:[30][31]

- Growth of or clitoral engorgement occurs.

- Growth of human growth hormone occurs.[32]

- Completion of bone maturation and termination of growth. This occurs indirectly via metabolitesand hence more gradually in men than women.

- Increased muscle strength and mass, shoulders become broader and rib cage expands, deepening of voice, growth of the Adam's apple.

- Enlargement of fatin face decreases.

- Pubic hair extends to thighs and up toward armpit hair.

Adult

Testosterone is necessary for normal

Adult testosterone effects are more clearly demonstrable in males than in females, but are likely important to both sexes. Some of these effects may decline as testosterone levels might decrease in the later decades of adult life.[36]

The brain is also affected by this sexual differentiation;

There are some differences between a male and female brain that may be due to different testosterone levels, one of them being size: the male human brain is, on average, larger.[38]

Health effects

Testosterone does not appear to increase the risk of developing prostate cancer. In people who have undergone testosterone deprivation therapy, testosterone increases beyond the castrate level have been shown to increase the rate of spread of an existing prostate cancer.[39][40][41]

Conflicting results have been obtained concerning the importance of

High androgen levels are associated with

Attention, memory, and spatial ability are key cognitive functions affected by testosterone in humans. Preliminary evidence suggests that low testosterone levels may be a risk factor for cognitive decline and possibly for dementia of the Alzheimer's type,[46][47][48][49] a key argument in life extension medicine for the use of testosterone in anti-aging therapies. Much of the literature, however, suggests a curvilinear or even quadratic relationship between spatial performance and circulating testosterone,[50] where both hypo- and hypersecretion (deficient- and excessive-secretion) of circulating androgens have negative effects on cognition.

Immune system and inflammation

Testosterone deficiency is associated with an increased risk of

Medical use

Testosterone is used as a medication for the treatment of

Testosterone is included in the

Common

2020 guidelines from the

No immediate short term effects on mood or behavior were found from the administration of supraphysiologic doses of testosterone for 10 weeks on 43 healthy men.[60]

Behavioural correlations

Sexual arousal

Testosterone levels follow a circadian rhythm that peaks early each day, regardless of sexual activity.[61]

In women, correlations may exist between positive orgasm experience and testosterone levels. Studies have shown small or inconsistent correlations between testosterone levels and male orgasm experience, as well as sexual assertiveness in both sexes.[62][63]

Sexual arousal and

Mammalian studies

Studies conducted in rats have indicated that their degree of sexual arousal is sensitive to reductions in testosterone. When testosterone-deprived rats were given medium levels of testosterone, their sexual behaviours (copulation, partner preference, etc.) resumed, but not when given low amounts of the same hormone. Therefore, these mammals may provide a model for studying clinical populations among humans with sexual arousal deficits such as hypoactive sexual desire disorder.[66]

Every mammalian species examined demonstrated a marked increase in a male's testosterone level upon encountering a novel female. The reflexive testosterone increases in male mice is related to the male's initial level of sexual arousal.[67]

In non-human primates, it may be that testosterone in puberty stimulates sexual arousal, which allows the primate to increasingly seek out sexual experiences with females and thus creates a sexual preference for females.[68] Some research has also indicated that if testosterone is eliminated in an adult male human or other adult male primate's system, its sexual motivation decreases, but there is no corresponding decrease in ability to engage in sexual activity (mounting, ejaculating, etc.).[68]

In accordance with sperm competition theory, testosterone levels are shown to increase as a response to previously neutral stimuli when conditioned to become sexual in male rats.[69] This reaction engages penile reflexes (such as erection and ejaculation) that aid in sperm competition when more than one male is present in mating encounters, allowing for more production of successful sperm and a higher chance of reproduction.

Males

In men, higher levels of testosterone are associated with periods of sexual activity.[70][71]

Men who watch a sexually explicit movie have an average increase of 35% in testosterone, peaking at 60–90 minutes after the end of the film, but no increase is seen in men who watch sexually neutral films.[72] Men who watch sexually explicit films also report increased motivation and competitiveness, and decreased exhaustion.[73] A link has also been found between relaxation following sexual arousal and testosterone levels.[74]

Females

Androgens may modulate the physiology of vaginal tissue and contribute to female genital sexual arousal.[75] Women's level of testosterone is higher when measured pre-intercourse vs. pre-cuddling, as well as post-intercourse vs. post-cuddling.[76] There is a time lag effect when testosterone is administered, on genital arousal in women. In addition, a continuous increase in vaginal sexual arousal may result in higher genital sensations and sexual appetitive behaviors.[77]

When females have a higher baseline level of testosterone, they have higher increases in sexual arousal levels but smaller increases in testosterone, indicating a ceiling effect on testosterone levels in females. Sexual thoughts also change the level of testosterone but not the level of cortisol in the female body, and hormonal contraceptives may affect the variation in testosterone response to sexual thoughts.[78]

Testosterone may prove to be an effective treatment in female sexual arousal disorders,[79] and is available as a dermal patch. There is no FDA-approved androgen preparation for the treatment of androgen insufficiency; however, it has been used as an off-label use to treat low libido and sexual dysfunction in older women. Testosterone may be a treatment for postmenopausal women as long as they are effectively estrogenized.[79]

Romantic relationships

Falling in love has been linked with decreases in men's testosterone levels while mixed changes are reported for women's testosterone levels.[80][81] There has been speculation that these changes in testosterone result in the temporary reduction of differences in behavior between the sexes.[81] However, the testosterone changes observed do not seem to be maintained as relationships develop over time.[80][81]

Men who produce less testosterone are more likely to be in a relationship[82] or married,[83] and men who produce more testosterone are more likely to divorce.[83] Marriage or commitment could cause a decrease in testosterone levels.[84] Single men who have not had relationship experience have lower testosterone levels than single men with experience. It is suggested that these single men with prior experience are in a more competitive state than their non-experienced counterparts.[85] Married men who engage in bond-maintenance activities such as spending the day with their spouse or child have no different testosterone levels compared to times when they do not engage in such activities. Collectively, these results suggest that the presence of competitive activities rather than bond-maintenance activities is more relevant to changes in testosterone levels.[86]

Men who produce more testosterone are more likely to engage in extramarital sex.[83] Testosterone levels do not rely on physical presence of a partner; testosterone levels of men engaging in same-city and long-distance relationships are similar.[82] Physical presence may be required for women who are in relationships for the testosterone–partner interaction, where same-city partnered women have lower testosterone levels than long-distance partnered women.[87]

Fatherhood

Fatherhood decreases testosterone levels in men, suggesting that the emotions and behaviour tied to paternal care decrease testosterone levels. In humans and other species that utilize allomaternal care, paternal investment in offspring is beneficial to said offspring's survival because it allows the two parents to raise multiple children simultaneously. This increases the reproductive fitness of the parents because their offspring are more likely to survive and reproduce. Paternal care increases offspring survival due to increased access to higher quality food and reduced physical and immunological threats.[88] This is particularly beneficial for humans since offspring are dependent on parents for extended periods of time and mothers have relatively short inter-birth intervals.[89]

While the extent of paternal care varies between cultures, higher investment in direct child care has been seen to be correlated with lower average testosterone levels as well as temporary fluctuations.[90] For instance, fluctuation in testosterone levels when a child is in distress has been found to be indicative of fathering styles. If a father's testosterone levels decrease in response to hearing their baby cry, it is an indication of empathizing with the baby. This is associated with increased nurturing behavior and better outcomes for the infant.[91]

Motivation

Testosterone levels play a major role in risk-taking during financial decisions.[92][93] Higher testosterone levels in men reduce the risk of becoming or staying unemployed.[94] Research has also found that heightened levels of testosterone and cortisol are associated with an increased risk of impulsive and violent criminal behavior.[95] On the other hand, elevated testosterone in men may increase their generosity, primarily to attract a potential mate.[96][97]

Aggression and criminality

This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (June 2023) |

Most studies support a link between adult criminality and testosterone.

There are two theories on the role of testosterone in aggression and competition.[105] The first one is the challenge hypothesis which states that testosterone would increase during puberty, thus facilitating reproductive and competitive behavior which would include aggression.[105] It is therefore the challenge of competition among males of the species that facilitates aggression and violence.[105] Studies conducted have found direct correlation between testosterone and dominance, especially among the most violent criminals in prison who had the highest testosterone levels.[105] The same research also found fathers (those outside competitive environments) had the lowest testosterone levels compared to other males.[105]

The second theory is similar and is known as "evolutionary neuroandrogenic (ENA) theory of male aggression".[106][107] Testosterone and other androgens have evolved to masculinize a brain in order to be competitive even to the point of risking harm to the person and others. By doing so, individuals with masculinized brains as a result of pre-natal and adult life testosterone and androgens enhance their resource acquiring abilities in order to survive, attract and copulate with mates as much as possible.[106] The masculinization of the brain is not just mediated by testosterone levels at the adult stage, but also testosterone exposure in the womb as a fetus. Higher pre-natal testosterone indicated by a low digit ratio as well as adult testosterone levels increased risk of fouls or aggression among male players in a soccer game.[108] Studies have also found higher pre-natal testosterone or lower digit ratio to be correlated with higher aggression in males.[109][110][111][112][113]

The rise in testosterone levels during competition predicted aggression in males but not in females.[114] Subjects who interacted with hand guns and an experimental game showed rise in testosterone and aggression.[115] Natural selection might have evolved males to be more sensitive to competitive and status challenge situations and that the interacting roles of testosterone are the essential ingredient for aggressive behaviour in these situations.[116] Testosterone mediates attraction to cruel and violent cues in men by promoting extended viewing of violent stimuli.[117] Testosterone-specific structural brain characteristic can predict aggressive behaviour in individuals.[118]

The Annual NY Academy of Sciences has also found anabolic steroid use (which increases testosterone) to be higher in teenagers, and this was associated with increased violence.[119] Studies have also found administered testosterone to increase verbal aggression and anger in some participants.[120]

A few studies indicate that the testosterone derivative estradiol (one form of estrogen) might play an important role in male aggression.[103][121][122][123] Estradiol is known to correlate with aggression in male mice.[124] Moreover, the conversion of testosterone to estradiol regulates male aggression in sparrows during breeding season.[125] Rats who were given anabolic steroids that increase testosterone were also more physically aggressive to provocation as a result of "threat sensitivity".[126]

The relationship between testosterone and aggression may also function indirectly, as it has been proposed that testosterone does not amplify tendencies towards aggression but rather amplifies whatever tendencies will allow an individual to maintain social status when challenged. In most animals, aggression is the means of maintaining social status. However, humans have multiple ways of obtaining social status. This could explain why some studies find a link between testosterone and pro-social behaviour if pro-social behaviour is rewarded with social status. Thus the link between testosterone and aggression and violence is due to these being rewarded with social status.[127] The relationship may also be one of a "permissive effect" whereby testosterone does elevate aggression levels but only in the sense of allowing average aggression levels to be maintained; chemically or physically castrating the individual will reduce aggression levels (though it will not eliminate them) but the individual only needs a small-level of pre-castration testosterone to have aggression levels to return to normal, which they will remain at even if additional testosterone is added. Testosterone may also simply exaggerate or amplify existing aggression; for example, chimpanzees who receive testosterone increases become more aggressive to chimps lower than them in the social hierarchy but will still be submissive to chimps higher than them. Testosterone thus does not make the chimpanzee indiscriminately aggressive but instead amplifies his pre-existing aggression towards lower-ranked chimps.[128]

In humans, testosterone appears more to promote status-seeking and social dominance than simply increasing physical aggression. When controlling for the effects of belief in having received testosterone, women who have received testosterone make fairer offers than women who have not received testosterone.[129]

Fairness

Testosterone might encourage fair behavior. For one study, subjects took part in a behavioral experiment where the distribution of a real amount of money was decided. The rules allowed both fair and unfair offers. The negotiating partner could subsequently accept or decline the offer. The fairer the offer, the less probable a refusal by the negotiating partner. If no agreement was reached, neither party earned anything. Test subjects with an artificially enhanced testosterone level generally made better, fairer offers than those who received placebos, thus reducing the risk of a rejection of their offer to a minimum. Two later studies have empirically confirmed these results.[130][131][132] However men with high testosterone were significantly 27% less generous in an ultimatum game.[133]

Biological activity

Free testosterone

Steroid hormone activity

The effects of testosterone in humans and other

Androgen receptors occur in many different vertebrate body system tissues, and both males and females respond similarly to similar levels. Greatly differing amounts of testosterone prenatally, at puberty, and throughout life account for a share of biological differences between males and females.

The bones and the brain are two important tissues in humans where the primary effect of testosterone is by way of aromatization to estradiol. In the bones, estradiol accelerates ossification of cartilage into bone, leading to closure of the epiphyses and conclusion of growth. In the central nervous system, testosterone is aromatized to estradiol. Estradiol rather than testosterone serves as the most important feedback signal to the hypothalamus (especially affecting LH secretion).[147][failed verification] In many mammals, prenatal or perinatal "masculinization" of the sexually dimorphic areas of the brain by estradiol derived from testosterone programs later male sexual behavior.[148]

Neurosteroid activity

Testosterone, via its

Testosterone has been found to act as an

Testosterone is an antagonist of the sigma-1 receptor (Ki = 1,014 or 201 nM).[153] However, the concentrations of testosterone required for binding the receptor are far above even total circulating concentrations of testosterone in adult males (which range between 10 and 35 nM).[154]

Biochemistry

Biosynthesis

Like other

The largest amounts of testosterone (>95%) are produced by the

| Sex | Sex hormone | Reproductive phase |

Blood production rate |

Gonadal secretion rate |

Metabolic clearance rate |

Reference range (serum levels) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI units | Non-SI units | ||||||

| Men | Androstenedione | –

|

2.8 mg/day | 1.6 mg/day | 2200 L/day | 2.8–7.3 nmol/L | 80–210 ng/dL |

| Testosterone | –

|

6.5 mg/day | 6.2 mg/day | 950 L/day | 6.9–34.7 nmol/L | 200–1000 ng/dL | |

| Estrone | –

|

150 μg/day | 110 μg/day | 2050 L/day | 37–250 pmol/L | 10–70 pg/mL | |

| Estradiol | –

|

60 μg/day | 50 μg/day | 1600 L/day | <37–210 pmol/L | 10–57 pg/mL | |

| Estrone sulfate | –

|

80 μg/day | Insignificant | 167 L/day | 600–2500 pmol/L | 200–900 pg/mL | |

| Women | Androstenedione | –

|

3.2 mg/day | 2.8 mg/day | 2000 L/day | 3.1–12.2 nmol/L | 89–350 ng/dL |

| Testosterone | –

|

190 μg/day | 60 μg/day | 500 L/day | 0.7–2.8 nmol/L | 20–81 ng/dL | |

| Estrone | Follicular phase | 110 μg/day | 80 μg/day | 2200 L/day | 110–400 pmol/L | 30–110 pg/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 260 μg/day | 150 μg/day | 2200 L/day | 310–660 pmol/L | 80–180 pg/mL | ||

| Postmenopause | 40 μg/day | Insignificant | 1610 L/day | 22–230 pmol/L | 6–60 pg/mL | ||

| Estradiol | Follicular phase | 90 μg/day | 80 μg/day | 1200 L/day | <37–360 pmol/L | 10–98 pg/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 250 μg/day | 240 μg/day | 1200 L/day | 699–1250 pmol/L | 190–341 pg/mL | ||

| Postmenopause | 6 μg/day | Insignificant | 910 L/day | <37–140 pmol/L | 10–38 pg/mL | ||

| Estrone sulfate | Follicular phase | 100 μg/day | Insignificant | 146 L/day | 700–3600 pmol/L | 250–1300 pg/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 180 μg/day | Insignificant | 146 L/day | 1100–7300 pmol/L | 400–2600 pg/mL | ||

| Progesterone | Follicular phase | 2 mg/day | 1.7 mg/day | 2100 L/day | 0.3–3 nmol/L | 0.1–0.9 ng/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 25 mg/day | 24 mg/day | 2100 L/day | 19–45 nmol/L | 6–14 ng/mL | ||

Notes and sources

Notes: "The concentration of a steroid in the circulation is determined by the rate at which it is secreted from glands, the rate of metabolism of precursor or prehormones into the steroid, and the rate at which it is extracted by tissues and metabolized. The secretion rate of a steroid refers to the total secretion of the compound from a gland per unit time. Secretion rates have been assessed by sampling the venous effluent from a gland over time and subtracting out the arterial and peripheral venous hormone concentration. The metabolic clearance rate of a steroid is defined as the volume of blood that has been completely cleared of the hormone per unit time. The production rate of a steroid hormone refers to entry into the blood of the compound from all possible sources, including secretion from glands and conversion of prohormones into the steroid of interest. At steady state, the amount of hormone entering the blood from all sources will be equal to the rate at which it is being cleared (metabolic clearance rate) multiplied by blood concentration (production rate = metabolic clearance rate × concentration). If there is little contribution of prohormone metabolism to the circulating pool of steroid, then the production rate will approximate the secretion rate." Sources: See template. | |||||||

Regulation

In males, testosterone is synthesized primarily in

The amount of testosterone synthesized is regulated by the hypothalamic–pituitary–testicular axis .[160] When testosterone levels are low, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is released by the hypothalamus, which in turn stimulates the pituitary gland to release FSH and LH. These latter two hormones stimulate the testis to synthesize testosterone. Finally, increasing levels of testosterone through a negative feedback loop act on the hypothalamus and pituitary to inhibit the release of GnRH and FSH/LH, respectively.

Factors affecting testosterone levels may include:

- Age: Testosterone levels gradually reduce as men age.andropause or late-onset hypogonadism.[163]

- Exercise: Resistance training increases testosterone levels acutely,[164] however, in older men, that increase can be avoided by protein ingestion.[165] Endurance training in men may lead to lower testosterone levels.[166]

- Nutrients: Vitamin A deficiency may lead to sub-optimal plasma testosterone levels.[167] The secosteroid vitamin D in levels of 400–1000 IU/d (10–25 µg/d) raises testosterone levels.[168] Zinc deficiency lowers testosterone levels[169] but over-supplementation has no effect on serum testosterone.[170] There is limited evidence that low-fat diets may reduce total and free testosterone levels in men.[171]

- Weight loss: Reduction in weight may result in an increase in testosterone levels. Fat cells synthesize the enzyme aromatase, which converts testosterone, the male sex hormone, into estradiol, the female sex hormone.[172] However no clear association between body mass index and testosterone levels has been found.[173]

- Miscellaneous: Sleep: (REM sleep) increases nocturnal testosterone levels.[174]

- Behavior: Dominance challenges can, in some cases, stimulate increased testosterone release in men.[175]

- Foods: Natural or man-made Licorice can decrease the production of testosterone and this effect is greater in females.[179]

Distribution

The plasma protein binding of testosterone is 98.0 to 98.5%, with 1.5 to 2.0% free or unbound.[180] It is bound 65% to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and 33% bound weakly to albumin.[181]

| Compound | Group | Level (nM) | Free (%) | SHBG (%) | CBG (%) |

Albumin (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone | Adult men | 23.0 | 2.23 | 44.3 | 3.56 | 49.9 |

| Adult women | ||||||

| Follicular phase | 1.3 | 1.36 | 66.0 | 2.26 | 30.4 | |

| Luteal phase | 1.3 | 1.37 | 65.7 | 2.20 | 30.7 | |

| Pregnancy | 4.7 | 0.23 | 95.4 | 0.82 | 3.6 | |

| Dihydrotestosterone | Adult men | 1.70 | 0.88 | 49.7 | 0.22 | 39.2 |

| Adult women | ||||||

| Follicular phase | 0.65 | 0.47 | 78.4 | 0.12 | 21.0 | |

| Luteal phase | 0.65 | 0.48 | 78.1 | 0.12 | 21.3 | |

| Pregnancy | 0.93 | 0.07 | 97.8 | 0.04 | 21.2 | |

| Sources: See template. | ||||||

Metabolism

Testosterone metabolism in humans

hydroxyl (–OH) groups . |

Both testosterone and 5α-DHT are

In the hepatic 17-ketosteroid pathway of testosterone metabolism, testosterone is converted in the liver by 5α-reductase and 5β-reductase into 5α-DHT and the inactive

In addition to conjugation and the 17-ketosteroid pathway, testosterone can also be

Two of the immediate metabolites of testosterone, 5α-DHT and

Levels

Total levels of testosterone in the body have been reported as 264 to 916 ng/dL (nanograms per deciliter) in non-obese European and American men age 19 to 39 years,[196] while mean testosterone levels in adult men have been reported as 630 ng/dL.[197] Although commonly used as a reference range,[198] some physicians have disputed the use of this range to determine hypogonadism.[199][200] Several professional medical groups have recommended that 350 ng/dL generally be considered the minimum normal level,[201] which is consistent with previous findings.[202][non-primary source needed][medical citation needed] Levels of testosterone in men decline with age.[196] In women, mean levels of total testosterone have been reported to be 32.6 ng/dL.[203][204] In women with hyperandrogenism, mean levels of total testosterone have been reported to be 62.1 ng/dL.[203][204]

| Total testosterone | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | Age range | Male | Female | ||

| Values | SI units | Values | SI units | ||

| Infant | Premature (26–28 weeks) | 59–125 ng/dL | 2.047–4.337 nmol/L | 5–16 ng/dL | 0.173–0.555 nmol/L |

| Premature (31–35 weeks) | 37–198 ng/dL | 1.284–6.871 nmol/L | 5–22 ng/dL | 0.173–0.763 nmol/L | |

| Newborn | 75–400 ng/dL | 2.602–13.877 nmol/L | 20–64 ng/dL | 0.694–2.220 nmol/L | |

| Child | 1–6 years | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 7–9 years | 0–8 ng/dL | 0–0.277 nmol/L | 1–12 ng/dL | 0.035–0.416 nmol/L | |

| Just before puberty | 3–10 ng/dL* | 0.104–0.347 nmol/L* | <10 ng/dL* | <0.347 nmol/L* | |

| Puberty | 10–11 years | 1–48 ng/dL | 0.035–1.666 nmol/L | 2–35 ng/dL | 0.069–1.214 nmol/L |

| 12–13 years | 5–619 ng/dL | 0.173–21.480 nmol/L | 5–53 ng/dL | 0.173–1.839 nmol/L | |

| 14–15 years | 100–320 ng/dL | 3.47–11.10 nmol/L | 8–41 ng/dL | 0.278–1.423 nmol/L | |

| 16–17 years | 200–970 ng/dL* | 6.94–33.66 nmol/L* | 8–53 ng/dL | 0.278–1.839 nmol/L | |

| Adult | ≥18 years | 350–1080 ng/dL* | 12.15–37.48 nmol/L* | – | – |

| 20–39 years | 400–1080 ng/dL | 13.88–37.48 nmol/L | – | – | |

| 40–59 years | 350–890 ng/dL | 12.15–30.88 nmol/L | – | – | |

| ≥60 years | 350–720 ng/dL | 12.15–24.98 nmol/L | – | – | |

| Premenopausal | – | – | 10–54 ng/dL | 0.347–1.873 nmol/L | |

| Postmenopausal | – | – | 7–40 ng/dL | 0.243–1.388 nmol/L | |

| Bioavailable testosterone | |||||

| Stage | Age range | Male | Female | ||

| Values | SI units | Values | SI units | ||

| Child | 1–6 years | 0.2–1.3 ng/dL | 0.007–0.045 nmol/L | 0.2–1.3 ng/dL | 0.007–0.045 nmol/L |

| 7–9 years | 0.2–2.3 ng/dL | 0.007–0.079 nmol/L | 0.2–4.2 ng/dL | 0.007–0.146 nmol/L | |

| Puberty | 10–11 years | 0.2–14.8 ng/dL | 0.007–0.513 nmol/L | 0.4–19.3 ng/dL | 0.014–0.670 nmol/L |

| 12–13 years | 0.3–232.8 ng/dL | 0.010–8.082 nmol/L | 1.1–15.6 ng/dL | 0.038–0.541 nmol/L | |

| 14–15 years | 7.9–274.5 ng/dL | 0.274–9.525 nmol/L | 2.5–18.8 ng/dL | 0.087–0.652 nmol/L | |

| 16–17 years | 24.1–416.5 ng/dL | 0.836–14.452 nmol/L | 2.7–23.8 ng/dL | 0.094–0.826 nmol/L | |

| Adult | ≥18 years | ND | ND | – | – |

| Premenopausal | – | – | 1.9–22.8 ng/dL | 0.066–0.791 nmol/L | |

| Postmenopausal | – | – | 1.6–19.1 ng/dL | 0.055–0.662 nmol/L | |

| Free testosterone | |||||

| Stage | Age range | Male | Female | ||

| Values | SI units | Values | SI units | ||

| Child | 1–6 years | 0.1–0.6 pg/mL | 0.3–2.1 pmol/L | 0.1–0.6 pg/mL | 0.3–2.1 pmol/L |

| 7–9 years | 0.1–0.8 pg/mL | 0.3–2.8 pmol/L | 0.1–1.6 pg/mL | 0.3–5.6 pmol/L | |

| Puberty | 10–11 years | 0.1–5.2 pg/mL | 0.3–18.0 pmol/L | 0.1–2.9 pg/mL | 0.3–10.1 pmol/L |

| 12–13 years | 0.4–79.6 pg/mL | 1.4–276.2 pmol/L | 0.6–5.6 pg/mL | 2.1–19.4 pmol/L | |

| 14–15 years | 2.7–112.3 pg/mL | 9.4–389.7 pmol/L | 1.0–6.2 pg/mL | 3.5–21.5 pmol/L | |

| 16–17 years | 31.5–159 pg/mL | 109.3–551.7 pmol/L | 1.0–8.3 pg/mL | 3.5–28.8 pmol/L | |

| Adult | ≥18 years | 44–244 pg/mL | 153–847 pmol/L | – | – |

| Premenopausal | – | – | 0.8–9.2 pg/mL | 2.8–31.9 pmol/L | |

| Postmenopausal | – | – | 0.6–6.7 pg/mL | 2.1–23.2 pmol/L | |

| Sources: See template. | |||||

| Life stage | Tanner stage | Age range | Mean age | Levels range | Mean levels |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | Stage I | <10 years | – | <30 ng/dL | 5.8 ng/dL |

| Puberty | Stage II | 10–14 years | 12 years | <167 ng/dL | 40 ng/dL |

| Stage III | 12–16 years | 13–14 years | 21–719 ng/dL | 190 ng/dL | |

| Stage IV | 13–17 years | 14–15 years | 25–912 ng/dL | 370 ng/dL | |

| Stage V | 13–17 years | 15 years | 110–975 ng/dL | 550 ng/dL | |

| Adult | – | ≥18 years | – | 250–1,100 ng/dL | 630 ng/dL |

| Sources: [205][206][197][207][208] | |||||

Measurement

In measurements of testosterone in blood samples, different assay techniques can yield different results.[209][210] Immunofluorescence assays exhibit considerable variability in quantifying testosterone concentrations in blood samples due to the cross-reaction of structurally similar steroids, leading to overestimating the results. In contrast, the liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry method is more desirable: it offers superior specificity and precision, making it a more suitable choice for this application.[211]

Testosterone's bioavailable concentration is commonly determined using the Vermeulen calculation or more precisely using the modified Vermeulen method,[212][213] which considers the dimeric form of sex hormone-binding globulin.[214]

Both methods use chemical equilibrium to derive the concentration of bioavailable testosterone: in circulation, testosterone has two major binding partners, albumin (weakly bound) and sex hormone-binding globulin (strongly bound). These methods are described in detail in the accompanying figure.

-

Dimeric sex hormone-binding globulin with its testosterone ligands

-

Two methods for determining the concentration of bioavailable testosterone

Distribution

Testosterone has been detected at variably higher and lower levels among men of various nations and from various backgrounds, explanations for the causes of this have been relatively diverse.[215][216]

People from nations of the Eurasian Steppe and Central Asia, such as Mongolia, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, have consistently been detected to have had significantly elevated levels of Testosterone,[217] while people from Central European and Baltic nations such as the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Latvia and Estonia have been found to have had significantly decreased levels of Testosterone.[218]

The region with the highest-ever tested levels of Testosterone is

History and production

A

In 1927, the University of Chicago's Professor of Physiologic Chemistry, Fred C. Koch, established easy access to a large source of bovine testicles – the Chicago stockyards – and recruited students willing to endure the tedious work of extracting their isolates. In that year, Koch and his student, Lemuel McGee, derived 20 mg of a substance from a supply of 40 pounds of bovine testicles that, when administered to castrated roosters, pigs and rats, re-masculinized them.

The Organon group in the Netherlands were the first to isolate the hormone, identified in a May 1935 paper "On Crystalline Male Hormone from Testicles (Testosterone)".

The

The partial synthesis in the 1930s of abundant, potent

Like other androsteroids, testosterone is manufactured industrially from microbial fermentation of plant cholesterol (e.g., from soybean oil). In the early 2000s, the steroid market weighed around one million tonnes and was worth $10 billion, making it the 2nd largest biopharmaceutical market behind antibiotics.[232]

Other species

Testosterone is observed in most vertebrates. Testosterone and the classical nuclear

See also

- List of androgens/anabolic steroids

- List of human hormones

References

- ISBN 978-1-4398-5511-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-29738-7.

- ^ "Understanding the risks of performance-enhancing drugs". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on April 21, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ PMID 3549275.

- PMID 19707253.

- PMID 19011293.

- PMID 8757191.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-107-01290-5.

- PMID 14981046.

- PMID 6025472.

- PMID 5843701.

- ISBN 978-0-07-135739-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Testosterone". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. December 4, 2015. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ Liverman CT, Blazer DG, et al. (Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Assessing the Need for Clinical Trials of Testosterone Replacement Therapy) (2004). "Introduction". Testosterone and Aging: Clinical Research Directions (Report). National Academies Press (US). Archived from the original on January 10, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ "What is Prohibited". World Anti-Doping Agency. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- S2CID 32366484.

- from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-319-29195-6. Archivedfrom the original on April 7, 2024. Retrieved April 6, 2024.

- PMID 12017555.

- ^ Sfetcu N (May 2, 2014). Health & Drugs: Disease, Prescription & Medication. Nicolae Sfetcu. Archived from the original on November 18, 2023. Retrieved November 21, 2022.

- ^ PMID 19403051.

- PMID 30381580.

- PMID 29736184.

- S2CID 33519930.

- PMID 4715291.

- PMID 1379488.

- S2CID 23978105.

- ^ .

- ISBN 978-0-495-60300-9. Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ^ S2CID 28274693.

- ISBN 978-1-259-02753-6.

- PMID 20501658.

- PMID 18505319. Archived from the original(PDF) on April 19, 2009.

- PMID 15820970.

- PMID 7758179.

- PMID 25295520.

- S2CID 20480423.

- PMID 17544382.

- PMID 19011298.

- PMID 18638000.

- PMID 18838208.

- PMID 17285783.

- PMID 19464009.

- PMID 18488876.

- from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- S2CID 13852805.

- PMID 15383512.

- S2CID 24803152.

- from the original on November 19, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- S2CID 7135870.

- ^ PMID 30582096.

- S2CID 184487697.

- ^ "List of Gender Dysphoria Medications (6 Compared)". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on April 26, 2020. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- PMID 16985841.

- FDA. March 3, 2015. Archivedfrom the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 13, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- S2CID 259176370.

- PMID 31905405.

- ^ Parry NM (January 7, 2020). "New Guideline for Testosterone Treatment in Men With 'Low T'". Medscape.com. Archived from the original on January 8, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- S2CID 73721690.

- PMID 5061159.

- S2CID 14588630.

- S2CID 40567580.

- PMID 10367606.

- PMID 135817.

- S2CID 1577450.

- S2CID 36436418.

- ^ S2CID 2214664.

- S2CID 42155431.

- S2CID 38283107.

- .

- S2CID 43495791.

- S2CID 41819670.

- S2CID 35309934.

- PMID 12007897.

- S2CID 5718960.

- PMID 10665617.

- from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ PMID 15889125.

- ^ PMID 31683520.

- ^ S2CID 24651931.

- ^ S2CID 22477678.

- ^ .

- .

- S2CID 33812118.

- S2CID 18107730.

- S2CID 30710035.

- S2CID 83046141.

- PMID 25843884.

- S2CID 438574.

- ^ Nauert R (October 30, 2015). "Parenting Skills Influenced by Testosterone Levels, Empathy". Psych Central. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- PMID 19706398.

- .

- S2CID 245383323.

- ^ Dolan EW (December 9, 2022). "Testosterone and cortisol levels are linked to criminal behavior, according to new research". Psypost - Psychology News. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ "Study shows that testosterone levels can have an impact on generosity". Archived from the original on April 2, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- PMID 27671627.

- S2CID 252285821.

- S2CID 647349.

- ^ Barber N (July 15, 2009). "Sex, violence, and hormones: Why young men are horny and violent". Psychology Today.

- .

- S2CID 23683791.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-373612-3.

- S2CID 23870320.

- ^ S2CID 26405251. Archived from the original(PDF) on January 9, 2016.

- ^ .

- .

- PMID 23588344.

- LiveScience. March 2, 2005. Archivedfrom the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- S2CID 17464657.

- PMID 22781854.

- S2CID 205303673.

- PMID 23972912.

- S2CID 32112035. Archived from the original(PDF) on January 26, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- S2CID 33952211.

- (PDF) from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- PMID 24367977.

- PMID 26431805.

- S2CID 36368056.

- PMID 12380846.

- ^ Goldman D, Lappalainen J, Ozaki N. Direct analysis of candidate genes in impulsive disorders. In: Bock G, Goode J, eds. Genetics of Criminal and Antisocial Behaviour. Ciba Foundation Symposium 194. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1996.

- S2CID 33226665.

- PMID 9253313.

- S2CID 32650274.

- S2CID 23990605.

- S2CID 29969145.

- PMID 30619017.

- ISBN 978-0-684-83891-5.

- (PDF) from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- S2CID 1305527.

- S2CID 4383859.

- S2CID 4413138.

- PMID 20016825.

- PMID 33553985.

- ^ a b "Testosteron liber" [Free testosterone] (in Romanian). Synevo Moldova. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- ^ PMID 30842823.

- ^ PMID 28673039.

- PMID 4062218.

- PMID 33139661.

- PMID 34197576.

- S2CID 23385663.

- PMID 11511858.

- PMID 19931639.

- PMID 25257522.

- S2CID 23918273.

- S2CID 34846760.

- PMID 16112267.

- PMID 18195084.

- PMID 22231829.

- ^ PMID 26908835.

- ^ PMID 21541365.

- ^ S2CID 26914550.

- PMID 28315270.

- ISBN 978-3-642-30725-6.

- PMID 1307739.

- PMID 3535074.

- S2CID 34863608.

- PMID 58744.

- ISBN 978-0-9627422-7-9.

- PMID 1377467.

- from the original on January 10, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016 – via www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- PMID 24407185.

- PMID 24793989.

- S2CID 11683565.

- S2CID 26280370.

- PMID 16268050.

- PMID 12141930.

- S2CID 206315145.

- PMID 8875519.

- PMID 17882141.

- S2CID 232246357.

- PMID 21849026.

- PMID 19889752.

- PMID 18519168.

- S2CID 6002474.

- S2CID 21961390.

- PMID 18804513.

- S2CID 206425734.

- PMID 12373628.

- ISBN 978-1-107-01290-5. Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- PMID 4044776.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2. Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-07575-6. Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- PMID 20186052.

- ISBN 978-94-009-8195-9. Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4665-9788-4.

- ISBN 978-0-387-08012-3.

- PMID 8092979.

- S2CID 25407830.

- ISBN 978-0-7020-3990-4.

- ISBN 978-1-139-45221-2.

- ISBN 978-0-9673355-4-4.

- ISBN 978-0-08-091906-5.

- ISBN 978-1-61779-222-9.

- S2CID 32619627.

- ^ PMID 28324103.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4557-5973-6. Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ "Testosterone, total". LabCorp. Archived from the original on December 20, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- S2CID 29122481.

- PMID 24797325.

- S2CID 30430279.

- PMID 21697255.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4511-7146-4. Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ PMID 15251757.

- ISBN 978-0-323-05405-8. Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ISBN 978-3-319-18371-8. Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-323-22592-2. Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-323-11246-8. Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ "Challenges in Testosterone Measurement, Data Interpretation, and Methodological Appraisal of Interventional Trials | the Journal of Sexual Medicine | Oxford Academic". Archived from the original on February 20, 2024. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "Testosterone concentrations, using different assays, in different types of ovarian insufficiency: A systematic review and meta-analysis | Human Reproduction Update | Oxford Academic". Archived from the original on February 20, 2024. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- PMID 38311999.

- PMID 16793931.

- .

- ^ "RCSB PDB - 1D2S". Crystal Structure of the N-Terminal Laminin G-Like Domain of SHBG in Complex with Dihydrotestosterone. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- PMID 32063884.

- from the original on October 2, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ antipufaadmin (March 4, 2022). "What Country Has The Highest Testosterone?". testosteronedecline.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ antipufaadmin (March 4, 2022). "What Country Has The Highest Testosterone?". testosteronedecline.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ "Testosterone Levels 100 Years Ago - TestosteroneDecline.com". testosteronedecline.com. October 13, 2021. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ Berthold AA (1849). "Transplantation der Hoden" [Transplantation of testis]. Arch. Anat. Physiol. Wiss. (in German). 16: 42–46.

- from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- .

- .

- .

- ^ PMID 11176375.

- .

- .

- PMID 7817189.

- .

- S2CID 40156824.

- ^ de Kruif P (1945). The Male Hormone. New York: Harcourt, Brace.

- PMID 32899410.

- S2CID 5790990.

- S2CID 33753909.

- ISBN 978-0-87893-617-5.

- S2CID 221810929.

- S2CID 31950471.

Further reading

- Fargo KN, Pak TR, Foecking EM, Jones KJ (2010). "Molecular Biology of Androgen Action: Perspectives on Neuroprotective and Neurotherapeutic Effects.". In Pfaff DW, Etgen AM (eds.). Molecular Mechanisms of Hormone Actions on Behavior. Elsevier Inc. pp. 1219–1246. ISBN 978-0-12-374939-0.

- Dowd NE (2013). "Sperm, testosterone, masculinities and fatherhood". Nevada Law Journal. 13 (2): 8. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- Celec P, Ostatníková D, Hodosy J (February 2015). "On the effects of testosterone on brain behavioral functions". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 9: 12. PMID 25741229.