Mental status examination

| Mental status examination | |

|---|---|

| ICD-9-CM | 94.09, 94.11 |

The mental status examination (MSE) is an important part of the clinical

The purpose of the MSE is to obtain a comprehensive cross-sectional description of the patient's

The data are collected through a combination of direct and indirect means: unstructured observation while obtaining the biographical and social information, focused questions about current symptoms, and formalised psychological tests.[2]

The MSE is not to be confused with the

Theoretical foundations

The MSE derives from an approach to

In practice, the MSE is a blend of empathic descriptive phenomenology and

Application

The mental status examination is a core skill of qualified (mental) health personnel. It is a key part of the initial psychiatric assessment in an

Domains

The mnemonic ASEPTIC can be used to remember the domains of the MSE:[14]

- A - Appearance/Behavior

- S - Speech

- E - Emotion (Mood and Affect)

- P - Perception

- T - Thought Content and Process

- I - Insight and Judgement

- C - Cognition

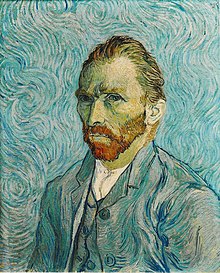

Appearance

Clinicians assess the physical aspects such as the appearance of a patient, including apparent age, height, weight, and manner of dress and grooming. Colorful or bizarre clothing might suggest

Attitude

Attitude, also known as rapport or cooperation,[17] refers to the patient's approach to the interview process and the quality of information obtained during the assessment.[18] Observations of attitude include whether the patient is cooperative, hostile, open or secretive.[14]

Behavior

Abnormalities of behavior, also called abnormalities of activity,

More global behavioural abnormalities may be noted, such as an increase in arousal and movement (described as

Mood and affect

The distinction between mood and affect in the MSE is subject to some disagreement. For example, Trzepacz and Baker (1993)[24] describe affect as "the external and dynamic manifestations of a person's internal emotional state" and mood as "a person's predominant internal state at any one time", whereas Sims (1995)[25] refers to affect as "differentiated specific feelings" and mood as "a more prolonged state or disposition". This article will use the Trzepacz and Baker (1993) definitions, with mood regarded as a current subjective state as described by the patient, and affect as the examiner's inferences of the quality of the patient's emotional state based on objective observation.[26][14]

Mood is described using the patient's own words, and can also be described in summary terms such as neutral,

Affect is described by labelling the apparent emotion conveyed by the person's nonverbal behavior (anxious, sad etc.), and also by using the parameters of appropriateness, intensity, range, reactivity and mobility. Affect may be described as appropriate or inappropriate to the current situation, and as

Speech

Speech is assessed by observing the patient's spontaneous speech, and also by using structured tests of specific language functions. This heading is concerned with the production of speech rather than the content of speech, which is addressed under thought process and thought content (see below). When observing the patient's spontaneous speech, the interviewer will note and comment on paralinguistic features such as the loudness, rhythm, prosody, intonation, pitch, phonation, articulation, quantity, rate, spontaneity and latency of speech.[14] Many acoustic features have been shown to be significantly altered in mental health disorders.[31] A structured assessment of speech includes an assessment of expressive language by asking the patient to name objects, repeat short sentences, or produce as many words as possible from a certain category in a set time. Simple language tests also form part of the

Language assessment will allow the recognition of medical conditions presenting with

Thought process

Thought content

A description of thought content would be the largest section of the MSE report. It would describe a patient's suicidal thoughts, depressed cognition,

Abnormalities of thought content are established by exploring individuals' thoughts in an open-ended conversational manner with regard to their intensity, salience, the emotions associated with the thoughts, the extent to which the thoughts are experienced as one's own and under one's control, and the degree of belief or conviction associated with the thoughts.[39][40][41]

Delusions

A delusion has three essential qualities: it can be defined as "a false, unshakeable idea or belief (1) which is out of keeping with the patient's educational, cultural and social background (2) ... held with extraordinary conviction and subjective certainty (3)",

The patient's delusions may be described within the SEGUE PM mnemonic as: somatic,

Delusional symptoms can be reported as on a continuum from: full symptoms (with no insight), partial symptoms (where they may start questioning these delusions), nil symptoms (where symptoms are resolved), or after complete treatment there are still delusional symptoms or ideas that could develop into delusions you can characterize this as residual symptoms.

Delusions can suggest several diseases such as

Other features differentiate diseases with delusions as well. Delusions may be described as mood-congruent (the delusional content in keeping with the mood), typical of manic or depressive psychosis, or mood-incongruent (delusional content not in keeping with the mood) which are more typical of schizophrenia. Delusions of control, or passivity experiences (in which the individual has the experience of the mind or body being under the influence or control of some kind of external force or agency), are typical of schizophrenia. Examples of this include experiences of thought withdrawal, thought insertion, thought broadcasting, and somatic passivity. Schneiderian first rank symptoms are a set of delusions and hallucinations which have been said to be highly suggestive of a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Delusions of guilt, delusions of poverty, and nihilistic delusions (belief that one has no mind or is already dead) are typical of depressive psychosis.

Overvalued Ideas

An overvalued idea is an emotionally charged belief that may be held with sufficient conviction to make believer emotionally charged or aggressive but that fails to possess all three characteristics of delusion—most importantly, incongruity with cultural norms. Therefore, any strong, fixed, false, but culturally normative belief can be considered an "overvalued idea".

Obsessions

An

Phobias

A phobia is "a dread of an object or situation that does not in reality pose any threat",[44] and is distinct from a delusion in that the patient is aware that the fear is irrational. A phobia is usually highly specific to certain situations and will usually be reported by the patient rather than being observed by the clinician in the assessment interview.

Preoccupations

Preoccupations are thoughts which are not fixed, false or intrusive, but have an undue prominence in the person's mind. Clinically significant preoccupations would include thoughts of suicide, homicidal thoughts, suspicious or fearful beliefs associated with certain personality disorders, depressive beliefs (for example that one is unloved or a failure), or the cognitive distortions of anxiety and depression.

Suicidal thoughts

The MSE contributes to clinical risk assessment by including a thorough exploration of any suicidal or hostile thought content. Assessment of suicide risk includes detailed questioning about the nature of the person's suicidal thoughts, belief about death, reasons for living, and whether the person has made any specific plans to end his or her life. The most important questions to ask are: Do you have suicidal feeling now; have you ever attempted suicide (highly correlated with future suicide attempts); do you have plans to commit suicide in the future; and, do you have any deadlines where you may commit suicide (e.g., numerology calculation, doomsday belief, Mother's Day, anniversary, Christmas).[45]

Perceptions

A

Hallucinations can occur in any of the five senses, although auditory and visual hallucinations are encountered more frequently than tactile (touch), olfactory (smell) or gustatory (taste) hallucinations. Auditory hallucinations are typical of

Cognition

This section of the MSE covers the patient's level of alertness, orientation, attention, memory, visuospatial functioning, language functions and executive functions. Unlike other sections of the MSE, use is made of structured tests in addition to unstructured observation. Alertness is a global observation of

Attention and concentration are assessed by several tests, commonly

Mild impairment of attention and concentration may occur in any

The MSE may include a brief neuropsychiatric examination in some situations. Frontal lobe pathology is suggested if the person cannot repetitively execute a motor sequence (e.g. "paper-scissors-rock"). The

Insight

The person's understanding of his or her mental illness is evaluated by exploring his or her explanatory account of the problem, and understanding of the treatment options. In this context,

Impaired insight is characteristic of psychosis and dementia, and is an important consideration in treatment planning and in assessing the capacity to consent to treatment.[56] Anosognosia is the clinical term for the condition in which the patient is unaware of their neurological deficit or psychiatric condition.[14][57]

Judgment

Judgment refers to the patient's capacity to make sound, reasoned and responsible decisions. One should frame judgement to the functions or domains that are normal versus impaired (e.g., poor judgement is isolated to petty theft, able to function in relationships, work, academics).

Traditionally, the MSE included the use of standard hypothetical questions such as "what would you do if you found a stamped, addressed envelope lying in the street?"; however contemporary practice is to inquire about how the patient has responded or would respond to real-life challenges and contingencies. Assessment would take into account the individual's

Impaired judgment is not specific to any diagnosis but may be a prominent feature of disorders affecting the frontal lobe of the brain. If a person's judgment is impaired due to mental illness, there might be implications for the person's safety or the safety of others.[58]

Cultural considerations

There are potential problems when the MSE is applied in a cross-cultural context, when the clinician and patient are from different cultural backgrounds. For example, the patient's culture might have different norms for appearance, behavior and display of emotions. Culturally normative spiritual and religious beliefs need to be distinguished from delusions and hallucinations — these may seem similar to one who does not understand that they have different roots. Cognitive assessment must also take the patient's language and educational background into account. Clinician's racial bias is another potential confounder. Consultation with cultural leaders in community or clinicians when working with Aboriginal people can help guide if any cultural phenomena has been considered when completing an MSE with Aboriginal patients and things to consider from a cross-cultural context.[59][60][61]

Children

There are particular challenges in carrying out an MSE with young children and others with limited language such as people with

See also

- Diagnostic classification and rating scales used in psychiatry

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- DSM-IV Codes

- Glossary of psychiatry

- Self-administered Gerocognitive Examination (SAGE)

Footnotes

- ISBN 0-19-506251-5.

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker (1993) Ch 1

- ^ Sims (1995) Ch 1

- S2CID 145391880.

- PMID 17108232.

- PMID 2685304.

- S2CID 20791751.

- ^ Vergare, Michael; Binder, Renee; Cook, Ian; et al. (June 2006). "Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults, Second Edition". American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines. PsychiatryOnline. Archived from the original on 2008-10-03. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ^ "History and Mental Status Examination". eMedicine. February 4, 2008. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker (1993) Preface

- ^ "Mental state examination examples". Monash University learning support. Archived from the original on 2008-06-16. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- PMID 7594361.

- ^ "Brief Mental Status Examination" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Mental Status Exam (MSE)". PsychDB. 2022-01-21. Retrieved 2023-10-26.

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker (1993) p. 13-19

- ^ Gelder, Mayou & Geddes (2005)

- ^ Sims (1995) p. 13

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker (1993) p. 19-21

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker (1993) p 21

- ^ German: holding against

- ^ Hamilton (1985) p 92-114

- ^ Sims (1995) p 274

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker (1993) p 21-38

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker (1993) p 39

- ^ Sims (1995) p 222

- ^ Supported for example by "Mental state examination: Mood and affect". Psychskills. Archived from the original on 2008-06-13. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ French: beautiful indifference "la belle indifference". Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Hamilton (1985) Ch 6

- ^ Sims (1995) Ch 16

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker (1993) Ch 3

- PMID 32128436.

- ^ See for example "Mental state examination: Cognitive function". Psychskills. Archived from the original on 2008-06-01. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Hamilton (1985) p 56-62

- ^ Sims (1995) Ch 9

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker (1993) Ch 4

- ^ Hamilton (1985) Ch 4

- ^ Sims (1995) Ch 8

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker (1993) p 83-91

- ^ Hamilton (1985) p 41-53

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker p 91-106

- ^ Sims (1995) p 118-125

- ^ Sims (1995 p 82)

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker p 101

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker p 103

- ^ Jacobs, Douglas; Baldessarini, Ross; Conwell, Yeates; et al. (November 2003). "Assessment and Treatment of Patients With Suicidal Behaviors". American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines. PsychiatryOnline. Archived from the original on 2008-08-28. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ^ Sims (1995) Ch 6

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker (1993) p 106-120

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker (1993) Ch 6

- ISBN 0-87488-449-7.

- ISBN 0-87488-596-5.

- ISBN 0-87488-699-6.

- ^ RB Taylor. Difficult Diagnosis Second Edition. New York, WB Saunders Co., 1992.

- ^ JN Walton. Brain's Diseases of the Nervous System Eighth Edition. New York, Oxford University Press,1977

- S2CID 25934331.

- PMID 8494061.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Trzepacz & Baker (1993) p 167-171

- PMID 30020733, retrieved 2023-10-26

- ^ Trzepacz & Baker (1993) Ch 7

- ^ "Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice – Indigenous Justice Clearinghouse". www.indigenousjustice.gov.au. Australian Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ Bhugra D & Bhui K (1997) Cross-cultural psychiatric assessment. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment (3):103-110

- ^ Sheldon M (August 1997). "Mental State Examination". Psychiatric Assessment in Remote Aboriginal Communities of Central Australia. Australian Academy of Medicine and Surgery. Archived from the original on 2008-07-19. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- ISBN 0-632-05361-5. pp 43-44

References

- Hamilton, Max (1985). Fish's clinical psychopathology. London: John Wright. ISBN 0-7236-0605-6.

- Sims, A. G. (1995). Symptoms in the mind: an introduction to descriptive psychopathology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. ISBN 0-7020-1788-4.

- Trzepacz, Paula T; Baker, Robert (1993). The psychiatric mental status examination. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506251-5.

- Adams, Yolonda, et al. (2010) Principles of Practice in Mental Health Assessment with Aboriginal Australians.

Further reading

- Recupero, Patricia R (2010). "The Mental Status Examination in the Age of the Internet". Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 38 (1): 15–26. PMID 20305070. Retrieved 20 November 2010.