Anorexia nervosa

| Anorexia nervosa | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Anorexia, AN |

| Differential diagnosis | Body dysmorphic disorder, bulimia nervosa, hyperthyroidism, inflammatory bowel disease, dysphagia, cancer[6][7] |

| Treatment | Cognitive behavioral therapy, hospitalisation to restore weight[1][8] |

| Prognosis | 5% risk of death over 10 years[4][9] |

| Frequency | 2.9 million (2015)[10] |

| Deaths | 600 (2015)[11] |

Anorexia nervosa (AN), often referred to simply as anorexia,[12] is an eating disorder characterized by food restriction, body image disturbance, fear of gaining weight, and an overpowering desire to be thin.[1]

Individuals with anorexia nervosa have a fear of being

Anorexia often develops during adolescence or young adulthood.

Treatment of anorexia involves restoring the patient back to a healthy weight, treating their underlying psychological problems, and addressing underlying maladaptive behaviors.

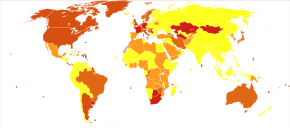

It is estimated to occur in 0.3% to 4.3% of women and 0.2% to 1% of men in Western countries at some point in their life.[22] About 0.4% of young women are affected in a given year and it is estimated to occur ten times more commonly among women than men.[4][22] It is unclear whether the increased incidence of anorexia observed in the 20th and 21st centuries is due to an actual increase in its frequency or simply due to improved diagnostic capabilities.[3] In 2013, it directly resulted in about 600 deaths globally, up from 400 deaths in 1990.[23] Eating disorders also increase a person's risk of death from a wide range of other causes, including suicide.[1][22] About 5% of people with anorexia die from complications over a ten-year period[4][9] with medical complications and suicide being the primary and secondary causes of death respectively.[24] Anorexia has one of the highest death rates among mental illnesses, second only to opioid overdoses.[25]

Signs and symptoms

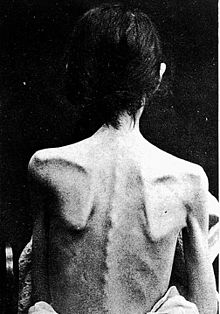

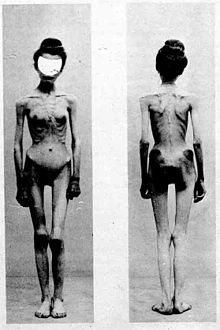

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by attempts to lose weight by way of starvation. A person with anorexia nervosa may exhibit a number of signs and symptoms, the type and severity of which may vary and be present but not readily apparent.[26] Though anorexia is typically recognized by the physical manifestations of the illness, it is a mental disorder that can be present at any weight.

Anorexia nervosa, and the associated

Signs and symptoms may be classified in various categories including: physical, cognitive, affective, behavioral and perceptual:

Physical symptoms

- A low body mass index for one's age and height (except in cases of atypical anorexia)[31]

- Rapid, continuous weight loss[32]

- Dry hair and skin, hair thinning, as well as hair loss[33]

- Low body temperature (hypothermia)[34]

- Raynaud Phenomenon[35]

- Hypotension or orthostatic hypotension

- Bradycardia or tachycardia

- Chronic fatigue[36]

- Insomnia

- Having severe muscle tension, aches and pains

- Irregular or absent menstrual[37] periods

- Infertility

- Gastrointestinal disease[38]

- Halitosis (from vomiting or starvation-induced ketosis)

- Abdominal distension

- Russell's Sign; can be a tell-tale sign of self-induced vomiting with scratches on the back of the hand

- Tooth erosion[39]

- Lanugo: soft, fine hair growing over the face and body[40]

- Orange discoloration of the skin, particularly the feet (Carotenosis)

Cognitive symptoms

- An obsession with counting calories and monitoring contents of food

- Preoccupation with food, recipes, or cooking; may cook elaborate dinners for others, but not eat the food themselves or consume a very small portion

- Admiration of thinner people

- Thoughts of being fat or not thin enough[41]

- An altered mental representation of one's body

- Impaired theory of mind, exacerbated by lower BMI and depression[42]

- Memory impairment

- Difficulty in abstract thinking and problem solving

- Rigid and inflexible thinking

- Poor self-esteem

- Hypercriticism and perfectionism

Affective symptoms

- Depression

- Ashamed of oneself or one's body

- Anxiety disorders

- Rapid mood swings

- Emotional dysregulation

- Alexithymia

Behavioral symptoms

- Compulsive weighing

- Regular body checking

- Food restriction, both in terms of caloric content and type (for example, macronutrientgroups)

- Food rituals, such as cutting food into tiny pieces and measuring it, refusing to eat around others, and hiding or discarding of food

- Purging, which may be achieved through self-induced vomiting, diuretics, or exercise. The goals of purging are various, including the prevention of weight gain, discomfort with the physical sensation of being full or bloated, and feelings of guilt or impurity.[43]

- Excessive exercise[44] or compulsive movement,[45] such as pacing

- Self harmingor self-loathing

- Social withdrawal and solitude, stemming from the avoidance of friends, family, and events where food may be present

- Excessive water consumption to create a false impression of satiety

- Excessive caffeine consumption

Perceptual symptoms

- Unawareness or denial of severity of condition (anosognosia),[46] which may prevent some from seeking recovery

- Perception of self as heavier or fatter than in reality, i.e., body image disturbance[13]

- Altered body schema, i.e., a distorted and unconscious perception of one's body size and shape that influences how the individual experiences their body during physical activities. For example, a patient with anorexia nervosa may genuinely fear that they cannot fit through a narrow passageway. However, due to their malnourished state, their body is significantly smaller than someone with a normal BMI who would actually struggle to fit through the same space. In spite of having a small frame, the patient's altered body schema leads them to perceive their body as larger than it is.[citation needed]

Interoception

Interoception involves the conscious and unconscious sense of the internal state of the body, and it has an important role in homeostasis and regulation of emotions.[47] Aside from noticeable physiological dysfunction, interoceptive deficits also prompt individuals with anorexia to concentrate on distorted perceptions of multiple elements of their body image.[48] This exists in both people with anorexia and in healthy individuals due to impairment in interoceptive sensitivity and interoceptive awareness.[48]

Aside from weight gain and outer appearance, people with anorexia also report abnormal bodily functions such as indistinct feelings of fullness.[49] This provides an example of miscommunication between internal signals of the body and the brain. Due to impaired interoceptive sensitivity, powerful cues of fullness may be detected prematurely in highly sensitive individuals, which can result in decreased calorie consumption and generate anxiety surrounding food intake in anorexia patients.[50] People with anorexia also report difficulty identifying and describing their emotional feelings and the inability to distinguish emotions from bodily sensations in general, called alexithymia.[49]

Interoceptive awareness and emotion are deeply intertwined, and could mutually impact each other in abnormalities.[50] Anorexia patients also exhibit emotional regulation difficulties that ignite emotionally-cued eating behaviors, such as restricting food or excessive exercising.[50] Impaired interoceptive sensitivity and interoceptive awareness can lead anorexia patients to adapt distorted interpretations of weight gain that are cued by physical sensations related to digestion (e.g., fullness).[50] Combined, these interoceptive and emotional elements could together trigger maladaptive and negatively reinforced behavioral responses that assist in the maintenance of anorexia.[50] In addition to metacognition, people with anorexia also have difficulty with social cognition including interpreting others' emotions, and demonstrating empathy.[51] Abnormal interoceptive awareness and interoceptive sensitivity shown through all of these examples have been observed so frequently in anorexia that they have become key characteristics of the illness.[49]

Comorbidity

Other psychological issues may factor into anorexia nervosa. Some pre-existing disorders can increase a person's likelihood to develop an eating disorder. Additionally, Anorexia Nervosa can contribute to the development of certain conditions.[52] The presence of psychiatric comorbidity has been shown to affect the severity and type of anorexia nervosa symptoms in both adolescents and adults.[53]

Causes

There is evidence for biological, psychological, developmental, and sociocultural risk factors, but the exact cause of eating disorders is unknown.[71]

Genetic

Anorexia nervosa is highly

A 2019 study found a genetic relationship with mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, obsessive–compulsive disorder, anxiety disorder and depression; and metabolic functioning with a negative correlation with fat mass, type 2 diabetes and leptin.[77]

Environmental

Neuroendocrine dysregulation: altered signaling of peptides that facilitate communication between the gut, brain and adipose tissue, such as ghrelin, leptin, neuropeptide Y and orexin, may contribute to the pathogenesis of anorexia nervosa by disrupting regulation of hunger and satiety.[81][82]

Anorexia nervosa is more likely to occur in a person's pubertal years. Some explanatory hypotheses for the rising prevalence of eating disorders in adolescence are "increase of adipose tissue in girls, hormonal changes of puberty, societal expectations of increased independence and autonomy that are particularly difficult for anorexic adolescents to meet; [and] increased influence of the peer group and its values."[85]

Anorexia as adaptation

Studies have

Psychological

Early theories of the cause of anorexia linked it to childhood sexual abuse or dysfunctional families;[95] evidence is conflicting, and well-designed research is needed.[71] The fear of food is known as sitiophobia[96] or cibophobia,[97] and is part of the differential diagnosis.[98][99] Other psychological causes of anorexia include low self-esteem, feeling as if there is lack of control, depression, anxiety, and loneliness.[100] People with anorexia are, in general, highly perfectionistic[101] and most have obsessive compulsive personality traits[102] which may facilitate sticking to a restricted diet.[103] It has been suggested that patients with anorexia are rigid in their thought patterns, and place a high level of importance upon being thin.[104][105] In the context of anorexia nervosa, this cognitive rigidity refers to the diminished ability to adapt one's behavioral approaches in response to changing circumstances. This weaker cognitive flexibility is a result of neurobiological factors, such as structural differences in prefrontal cortex connectivity, that contribute to the persistence of anorexic behaviors.[106][107]

Although the prevalence rates vary greatly, between 37% and 100%,[108] there appears to be an association between traumatic events and eating disorder diagnosis.[109] Approximately 72% of individuals with anorexia report experiencing a traumatic event prior to the onset of eating disorder symptoms, with binge-purge subtype reporting the highest rates.[108][109] There are many traumatic events that have been identified as possible risk factors for the development of anorexia, the first of which was childhood sexual abuse.[110]

As mentioned previously, the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among anorexia nervosa patients ranges from 4% to 24%.[54] A complicated symptom profile develops when trauma and anorexia meld; the bodily experience of the individual is changed and intrusive thoughts and sensations may be experienced.[110] Traumatic events can lead to intrusive and obsessive thoughts, and the symptom of anorexia that has been most closely linked to a PTSD diagnosis is increased obsessive thoughts pertaining to food.[110] Similarly, impulsivity is linked to the purge and binge-purge subtypes of anorexia, trauma, and PTSD.[109] Emotional trauma (e.g., invalidation, chaotic family environment in childhood) may lead to difficulty with emotions, particularly the identification of and how physical sensations contribute to the emotional response.[110]

When trauma is perpetrated on an individual, it can lead to feelings of not being safe within their own body.[110] Both physical and sexual abuse can lead to an individual seeing their body as belonging to an "other" and not to the "self".[110] Individuals who feel as though they have no control over their bodies due to trauma may use food as a means of control because the choice to eat is an unmatched expression of control.[110] By controlling the intake of food, individuals can decide when and how much they eat. Individuals, particularly children experiencing abuse, may feel a loss of control over their life, circumstances, and their own bodies. Particularly sexual abuse, but also physical abuse, can make individuals feel that the body is not a safe place and an object over which another has control. Starvation, in the case of anorexia, may also lead to reduction in the body as a sexual object, making starvation a solution. Restriction may also be a means by which the pain an individual is experiencing can be communicated.[110]

Sociological

Anorexia nervosa has been increasingly diagnosed since 1950;

Media effects

Persistent exposure to media that presents thin ideals may constitute a risk factor for body dysmorphia, leading to the development of anorexia nervosa. Western cultures that favor thin bodies as the beauty standard often have higher rates of anorexia nervosa.[120] Media sources such as magazines, television shows, and social media can contribute to body dissatisfaction and disordered eating globally, by emphasizing slimness rooted in Western ideals.[121] Among magazines popular with people aged 18 to 24, those with a predominantly male audience were more likely to feature advertisements and articles focused on body shape in relation to body culture rather than promoting healthy diet.[122] In addition to the direct effect of media on female body perception, media indirectly affects female body image through giving men a false perception of what a female body is meant to look like.[123] Body dissatisfaction and internalization of body ideals are risk factors for anorexia nervosa that threaten the health of both male and female populations, with a predominant focus on women.[124]

Another online aspect contributing to higher rates of eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa are websites and communities on social media that stress the importance attaining the "ideal" body. These communities promote anorexia nervosa through the use of religious metaphors, lifestyle demonstrations, and photo galleries or quotes meant to motivate the individual's pursuit of thinness (commonly referred to as "thinspiration," "bone-spiration,"[125] and "fitspiration").[126][127] These pro-anorexia websites reinforce internalization of body ideals and the importance of their attainment.[127]

Cultural

Cultural attitudes towards body image, beauty, and health also significantly impact the incidence of anorexia nervosa. There is a stark contrast between Western societies that idolize slimness and certain Eastern traditions that worship gods depicted with larger bodies,[128] and these varying cultural norms have varying influences on eating behaviors, self-perception, and anorexia in their respective cultures. For example, despite the fact that "fat phobia", or a fear of fat, is a key diagnostic criteria of anorexia by the DSM-5, anorexic patients in Asia rarely display this trait, as deep-rooted cultural values in Asian cultures praise larger bodies.[129] Fat phobia appears to be intricately linked to Western culture, encompassing how various cultural perceptions impact anorexia in various ways. It calls on the need for greater, diverse cultural consideration when looking at the diagnosis and experience of anorexia. For instance, in a cross-sectional study done on British South Asian adolescent English adolescent anorexia patients, it was found that both patients' symptom profiles differed. South Asians were less likely to exhibit fat-phobia as a symptom versus their English counterparts, instead exhibiting loss of appetite. Patients usually attributed their restricted food intake to somatic symptoms such as bloating, stomach pain, or lack of appetite.[130] However, both kinds of patients had distorted body images, implying the possibility of disordered eating and highlighting the need for cultural sensitivity when diagnosing anorexia.[131] Collectivist and individualistic values also play a role in the manifestation of symptoms. Patients in China are more likely to display denial or minimization of symptoms since they are culturally encouraged to use conceal their symptoms to preserve group harmony.[132]

These cultural differences are further empathized in research on the Caribbean island of Curaçao which revealed a substantially lower overall incidence of anorexia nervosa than that observed in the United States and Western Europe. Specifically, no cases were identified among the majority Black population, while the minority mixed and white population showed incidence rates similar to those in Western countries. This disparity highlights potential cultural variations in the development and presentation of anorexia nervosa, particularly when comparing Black women in Curaçao to those exposed to Western cultural influences.[133]

Notably, although these cultural distinctions persist, modernization and globalization slowly homogenize these attitudes.[128] Anorexia is increasingly tied to the pressures of a global culture that celebrates Western ideals of thinness. The spread of Western media, fashion, and lifestyle ideals across the globe has begun to shift perceptions and standards of beauty in diverse cultures, contributing to a rise in the incidence of anorexia in places they were once rare.[134] Anorexia, once primarily associated with Western culture, seems more than ever to be linked to the cultures of modernity and globalization.[citation needed]

However, unique cultural-specific phenotypes of disordered eating emerged prior to Western influence.[134] For example, restrictive eating patterns were found in Japan as early as the 18th century and fewer reports of eating disorders were found between 1868 and 1944, when rapid Westernization occurred.[135] Sex-specific stressors and cultural dynamics could be implicated in this independent development of anorexia nervosa symptomology.

Mechanisms

Evidence from physiological, pharmacological and neuroimaging studies suggest serotonin (also called 5-HT) may play a role in anorexia. While acutely ill, metabolic changes may produce a number of biological findings in people with anorexia that are not necessarily causative of the anorexic behavior. For example, abnormal hormonal responses to challenges with serotonergic agents have been observed during acute illness, but not recovery. Nevertheless, increased cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (a metabolite of serotonin), and changes in anorectic behavior in response to acute tryptophan depletion (tryptophan is a metabolic precursor to serotonin) support a role in anorexia. The activity of the 5-HT2A receptors has been reported to be lower in patients with anorexia in a number of cortical regions, evidenced by lower binding potential of this receptor as measured by PET or SPECT, independent of the state of illness. While these findings may be confounded by comorbid psychiatric disorders, taken as a whole they indicate serotonin in anorexia.[136][137] These alterations in serotonin have been linked to traits characteristic of anorexia such as obsessiveness, anxiety, and appetite dysregulation.[91]

Neuroimaging studies investigating the functional connectivity between brain regions have observed a number of alterations in networks related to cognitive control, introspection, and sensory function. Alterations in networks related to the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex may be related to excessive cognitive control of eating related behaviors. Similarly, altered somatosensory integration and introspection may relate to abnormal body image.[138] A review of functional neuroimaging studies reported reduced activations in "bottom up" limbic region and increased activations in "top down" cortical regions which may play a role in restrictive eating.[139]

Compared to controls, people who have recovered from anorexia show reduced activation in the reward system in response to food, and reduced correlation between self reported liking of a sugary drink and activity in the striatum and anterior cingulate cortex. Increased binding potential of 11C radiolabelled raclopride in the striatum, interpreted as reflecting decreased endogenous dopamine due to competitive displacement, has also been observed.[140]

Structural neuroimaging studies have found global reductions in both gray matter and white matter, as well as increased cerebrospinal fluid volumes. Regional decreases in the left hypothalamus, left inferior parietal lobe, right lentiform nucleus and right caudate have also been reported[141] in acutely ill patients. However, these alterations seem to be associated with acute malnutrition and largely reversible with weight restoration, at least in nonchronic cases in younger people.[142] In contrast, some studies have reported increased orbitofrontal cortex volume in currently ill and in recovered patients, although findings are inconsistent. Reduced white matter integrity in the fornix has also been reported.[143]

Diagnosis

A diagnostic assessment includes the person's current circumstances, biographical history, current symptoms, and family history. The assessment also includes a

DSM-5

Anorexia nervosa is classified under the Feeding and Eating Disorders in the latest revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM 5). There is no specific BMI cut-off that defines low weight required for the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa.[144][4]

The diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa (all of which needing to be met for diagnosis) are:[8][145]

- Restriction of energy intake relative to requirements leading to a low body weight. (Criterion A)

- Intense fear of gaining weight or persistent behaviors that interfere with gaining weight. (Criterion B)

- Disturbance in the way a person's weight or body shape is experienced or a lack of recognition about the risks of the low body weight. (Criterion C)

Relative to the previous version of the DSM (

Subtypes

There are two subtypes of AN:[27][147]

- Restrictive Type: In the most recent months leading up to the evaluation, the patient has not engaged in binging and purging via laxative or diuretic abuse, enemas, or self-induced vomiting. The weight loss accomplished in this patient is mainly through the use of one or more of the following methods: fasting, dieting, and excessive exercise.[148]

- Binge-eating / Purging Type: In the last few months, the patient has recurrently engaged in binge-purge cycles.[148]

Levels of severity

The use of the body mass index in the diagnosis of eating disorders has been controversial, largely owing to its oversimplification of health and failure to take into account complicating factors such as body composition or the initial bodyweight of the patient prior to the onset of AN.[149] As such, the DSM-5 does not have a strict BMI cutoff for the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa,[150] but it nevertheless uses BMI to establish levels of severity, which it states as follows:[151]

- Mild: BMI of greater than 17

- Moderate: BMI of 16–16.99

- Severe: BMI of 15–15.99

- Extreme: BMI of less than 15

Investigations

Medical tests to check for signs of physical deterioration in anorexia nervosa may be performed by a general physician or psychiatrist.

Physical examination:

- Blinded weight: The patient will strip and put on a surgical gown alone. The patient will step backwards onto the scale as the healthcare provider blocks the reading from the patient's line of vision.[citation needed]

- Orthostatic vitals: The patient lies completely flat for five minutes, and then, the medical provider measures the patient's blood pressure and heart rate. The patient stands up and stays stationary for two minutes. Then, the blood pressure and heart rate are assessed again, making note of any patient symptoms upon standing like dizziness. According to the College of Family Physicians of Canada, a change in orthostatic heart rate greater than 20 beats/minute or a change in orthostatic blood pressure greater than 10mmHg can warrant admission for an adolescent.[152]

- Examination of hands and arms for brittle nails, Russell's sign, swollen joints, lanugo, and self harm.[153]

- Auscultation of the chest for rubs, gallops, thrills, murmurs, and apex beat.[153]

- Examination of the face for puffiness, dental decay, swollen parotid glands, and conjunctival hemorrhage.[153]

Blood tests:

- triglycerides.[157]

- Serum cholinesterase test: a test of liver enzymes (acetylcholinesterase and pseudocholinesterase) useful as a test of liver function and to assess the effects of malnutrition.[158]

- protein deficiency, kidney function, bleeding disorders, and Crohn's Disease.[159]

- Luteinizing hormone (LH) response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH): Tests the pituitary glands' response to GnRh, a hormone produced in the hypothalamus. Hypogonadism is often seen in anorexia nervosa cases.[28]

- CK-MB), brain (CK-BB) and skeletal muscle (CK-MM).[160]

- Thyroid function tests: tests used to assess thyroid functioning by checking levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), thyroxine (T4), and triiodothyronine (T3).[164]

Additional medical screenings:

- Urinalysis: a variety of tests performed on the urine used in the diagnosis of medical disorders, to test for substance abuse, and as an indicator of overall health[165]

- Electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG): measures electrical activity of the heart. It can be used to detect various disorders such as hyperkalemia.[166]

- Electroencephalogram (EEG): measures the electrical activity of the brain. It can be used to detect abnormalities such as those associated with pituitary tumors.[167]

Differential diagnoses

A variety of medical and psychological conditions have been misdiagnosed as anorexia nervosa; in some cases the correct diagnosis was not made for more than ten years.[citation needed]

The distinction between binge purging anorexia, bulimia nervosa and Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorders (OSFED) is often difficult for non-specialist clinicians. A main factor differentiating binge-purge anorexia from bulimia is the gap in physical weight. Patients with bulimia nervosa are ordinarily at a healthy weight, or slightly overweight. Patients with binge-purge anorexia are commonly underweight.[168] Moreover, patients with the binge-purging subtype may be significantly underweight and typically do not binge-eat large amounts of food.[168] In contrast, those with bulimia nervosa tend to binge large amounts of food.[168] It is not unusual for patients with an eating disorder to "move through" various diagnoses as their behavior and beliefs change over time.[70]

Treatment

Treatment for people with anorexia nervosa should be individualized and tailored to each person's medical, psychological, and nutritional circumstances. Treating this condition with an interdisciplinary team is suggested so that the different health care professional specialties can help addresses the different challenges that can be associated with recovery.[169] Treatment for anorexia typically involves a combination of medical, psychological interventions such as therapy, and nutritional interventions (diet) interventions. Hospitalization may also be needed in some cases,[170] and the person requires a comprehensive medical assessment to help direct the treatment options. There is no conclusive evidence that any particular treatment approach for anorexia nervosa works better than others.[12][171] In some clinical settings a specific body image intervention is performed to reduce body dissatisfaction and body image disturbance. Although restoring the person's weight is the primary task at hand, optimal treatment also includes and monitors behavioral change in the individual as well.[20]

In general, treatment for anorexia nervosa aims to address three main areas:[172]

- Restoring the person to a healthy weight;

- Treating the psychological disorders related to the illness;

- Reducing or eliminating behaviors or thoughts that originally led to the disordered eating.[172]

Psychological support

Psychological support, often in the form of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), family-bases treatment, or psychotherapy aims to change distorted thoughts and behaviors around food, body image, and self-worth, with family-based therapy also being a key approach for younger patients.

Family-based therapy

Family-based treatment (FBT) may be more successful than individual therapy for adolescents with AN.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is useful in adolescents and adults with anorexia nervosa.[179] One of the most known psychotherapy in the field is CBT-E, an enhanced cognitive-behavior therapy specifically focus to eating disorder psychopathology. Acceptance and commitment therapy is a third-wave cognitive-behavioral therapy which has shown promise in the treatment of AN.[180] Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) is also used in treating anorexia nervosa.[181] Schema-Focused Therapy (a form of CBT) was developed by Dr. Jeffrey Young and is effective in helping patients identify origins and triggers for disordered eating.[182]

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy for individuals with AN is challenging as they may value being thin and may seek to maintain control and resist change.[183] Initially, developing a desire to change is fundamental.[184] There is no strong evidence to suggest one type of psychotherapy over another for treating anorexia nervosa in adults or adolescents.[169]

Diet

Diet is the most essential factor to work on in people with anorexia nervosa, and must be tailored to each person's needs. Food variety is important when establishing meal plans as well as foods that are higher in energy density, especially in

Historically, practitioners have slowly increased calories at a measured pace from a starting point of around 1,200 kcal/day.[44][186] However, as understanding of the process of weight restoration has improved, an approach that favors a higher starting point and a more rapid rate of increase has become increasingly common. In either approach, the end goal is typically in the range of 3,000 to 3,500 kcal/day.[186]

Extreme hunger

After experiencing prolonged significant calorie deficits, people often undergo extreme hunger (

Refeeding syndrome

Treatment professionals tend to be conservative with refeeding in anorexic patients due to the risk of refeeding syndrome (RFS), which occurs when a malnourished person is refed too quickly for their body to be able to adapt. Two of the most common indicators that RFS is occurring are low phosophate levels and low potassium levels.[189] RFS is most likely to happen in severely or extremely underweight anorexics, as well as when medical comorbidities, such as infection or cardiac failure, are present. In these circumstances, it is recommended to start refeeding more slowly but to build up rapidly as long as RFS does not occur. Recommendations on energy requirements in the most medically compromised patients vary, from 5–10 kcal/kg/day to 1900 kcal/day.[190][191] This risk-averse approach can lead to underfeeding, which results in poorer outcomes for short- and long-term recovery.[186]

Medication

Pharmaceuticals have limited benefit for anorexia itself.[192][144] There is a lack of good information from which to make recommendations concerning the effectiveness of antidepressants in treating anorexia.[193] Administration of olanzapine has been shown to result in a modest but statistically significant increase in body weight of anorexia nervosa patients.[194] Other types of medication that can be used to treat Anorexia Nervosa are Prozac and Zyprexa. Prozac is a type of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor which can be used to maintain a healthy weight in patients once they reach a healthy weight while Zyprexa is used to calm obsessive thinking and increase weight gain in patients.[195]

Admission to hospital

Patients with AN may be deemed to have a lack of insight regarding the necessity of treatment, and thus may be involuntarily treated without their consent.[170]: 1038 AN has a high mortality and patients admitted in a severely ill state to medical units are at particularly high risk.[196] Diagnosis can be challenging, risk assessment may not be performed accurately, consent and the need for compulsion may not be assessed appropriately, refeeding syndrome may be missed or poorly treated and the behavioural and family problems in AN may be missed or poorly managed.[197] Guidelines published by the Royal College of Psychiatrists recommend that medical and psychiatric experts work together in managing severely ill people with AN.[198]

Experience of treatment

Patients involved in treatment sometimes felt that treatment focused on biological aspects of body weight and eating behaviour change rather than their perceptions or emotional state.[199]: 8 Patients felt that a therapists trust in them shown by being treated as a complete person with their own capacities was significant.[199]: 9 Some patients defined recovery from AN in terms of reclaiming a lost identity.[199]: 10 Additionally, access to timely treatment can be hindered by systemic challenges within the medical system. Some individuals have reported experiencing delays in treatment, particularly when transitioning from adolescence to adulthood.[200]

Healthcare workers involved in the treatment of anorexia reported frustration and anger to setbacks in treatment and noncompliance and were afraid of patients dying. Some healthcare workers felt that they did not understand the treatment and that medical doctors were making decisions.

Prognosis

AN has the highest mortality rate of any psychological disorder.[9] The mortality rate is 11 to 12 times greater than in the general population, and the suicide risk is 56 times higher.[28] Half of women with AN achieve a full recovery, while an additional 20–30% may partially recover.[9][28] Not all people with anorexia recover completely: about 20% develop anorexia nervosa as a chronic disorder.[171] If anorexia nervosa is not treated, serious complications such as heart conditions[26] and kidney failure can arise and eventually lead to death.[202] The average number of years from onset to remission of AN is seven for women and three for men. After ten to fifteen years, 70% of people no longer meet the diagnostic criteria, but many still continue to have eating-related problems.[203] People who have autism recover more slowly, probably due to autism's effects on thinking patterns, such as reduced cognitive flexibility.[204]

Alexithymia (inability to identify and describe one's own emotions) influences treatment outcome.[192] Recovery is also viewed on a spectrum rather than black and white. According to the Morgan-Russell criteria, individuals can have a good, intermediate, or poor outcome. Even when a person is classified as having a "good" outcome, weight only has to be within 15% of average, and normal menstruation must be present in females. The good outcome also excludes psychological health. Recovery for people with anorexia nervosa is undeniably positive, but recovery does not mean a return to normal.[205]

Complications

Anorexia nervosa can have serious implications if its duration and severity are significant and if onset occurs before the completion of growth, pubertal maturation, or the attainment of peak bone mass.[206][medical citation needed] Complications specific to adolescents and children with anorexia nervosa can include growth retardation, as height gain may slow and can stop completely with severe weight loss or chronic malnutrition. In such cases, provided that growth potential is preserved, height increase can resume and reach full potential after normal intake is resumed.[207] Height potential is normally preserved if the duration and severity of illness are not significant or if the illness is accompanied by delayed bone age (especially prior to a bone age of approximately 15 years), as hypogonadism may partially counteract the effects of undernutrition on height by allowing for a longer duration of growth compared to controls.[medical citation needed] Appropriate early treatment can preserve height potential, and may even help to increase it in some post-anorexic subjects, due to factors such as long-term reduced estrogen-producing adipose tissue levels compared to premorbid levels.[medical citation needed] In some cases, especially where onset is before puberty, complications such as stunted growth and pubertal delay are usually reversible.[208]

Anorexia nervosa causes alterations in the female reproductive system; significant weight loss, as well as psychological stress and intense exercise, typically results in a

Hepatic steatosis, or fatty infiltration of the liver, can also occur, and is an indicator of malnutrition in children.

The most common gastrointestinal complications of anorexia nervosa are delayed stomach emptying and constipation, but also include elevated liver function tests, diarrhea, acute pancreatitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), difficulty swallowing, and, rarely, superior mesenteric artery syndrome.[214] Acid exposure from GERD and self-induced vomiting can cause dental problems, such as tooth enamel erosion and gum disease.[215][216] Delayed stomach emptying, or gastroparesis, often develops following food restriction and weight loss; the most common symptom is bloating with gas and abdominal distension, and often occurs after eating. Other symptoms of gastroparesis include early satiety, fullness, nausea, and vomiting. The symptoms may inhibit efforts at eating and recovery, but can be managed by limiting high-fiber foods, using liquid nutritional supplements, or using metoclopramide to increase emptying of food from the stomach.[214] Gastroparesis generally resolves when weight is regained.[citation needed]

Cardiac complications

Anorexia nervosa increases the risk of

Abnormalities in conduction and repolarization of the heart that can result from anorexia nervosa include

Some individuals may also have a decrease in cardiac contractility. Cardiac complications can be life-threatening, but the heart muscle generally improves with weight gain, and the heart normalizes in size over weeks to months, with recovery.

Relapse

Rates of relapse after treatment range 30–72% over a period of 2–26 months, with a rate of approximately 50% in 12 months after weight restoration.[220] Relapse occurs in approximately a third of people in hospital, and is greatest in the first six to eighteen months after release from an institution.[221] BMI or measures of body fat and leptin levels at discharge were the strongest predictors of relapse, as well as signs of eating psychopathology at discharge.[220] Duration of illness, age, severity, the proportion of AN binge-purge subtype, and presence of comorbidities are also contributing factors.[citation needed]

Epidemiology

This section needs expansion with: possible reasons for the higher prevalence in women. You can help by adding to it. (December 2024) |

Anorexia is estimated to occur in 0.9% to 4.3% of women and 0.2% to 0.3% of men in Western countries at some point in their life.[22] About 0.4% of young females are affected in a given year and it is estimated to occur three to ten times less commonly in males.[4][22][221][222] The cause of this disparity is not well-established but is thought to be linked to both biological and socio-cultural factors.[223] Rates in most of the developing world are unclear.[4] Often it begins during the teen years or young adulthood.[1] Medical students are a high risk group, with an overall estimated prevalence of 10.4% globally.[224]

The lifetime rate of

While anorexia became more commonly diagnosed during the 20th century it is unclear if this was due to an increase in its frequency or simply better diagnosis.[3] Most studies show that since at least 1970 the incidence of AN in adult women is fairly constant, while there is some indication that the incidence may have been increasing for girls aged between 14 and 20.[22]

Underrepresentation

In non-Westernized countries, including those in Africa (excluding South Africa), eating disorders are less frequently reported and studied compared to Western countries,[227] with available data mostly limited to case reports and isolated studies rather than prevalence investigations. Theories to explain these lower rates of eating disorders, lower reporting, and lower research rates in these countries include the attention to effects of westernisation and culture change on the prevalence of anorexia.[228][clarification needed]

Athletes are often overlooked as anorexic.[229] Research emphasizes the importance to take athletes' diet, weight and symptoms into account when diagnosing anorexia, instead of just looking at weight and BMI. For athletes, ritualized activities such as weigh-ins place emphasis on gaining and losing large amounts of weight, which may promote the development of eating disorders among them.[230] Furthermore, the competitive mindset of elite athletes makes them especially vulnerable to anorexia nervosa. The disorder is often largely rooted in a desire to maintain control over one’s own life. The highly competitive mindset that athletic pursuits can easily translate to the world of disordered eating. Eating becomes “like a game” or “challenge”, where the athlete is completely focused on “winning the game”; one elite swimmer with severe anorexia nervosa recalls that “it was always about losing more” and she “never wanted the game to be over”.[231]

Males

While anorexia nervosa is more commonly found in women, it can also affect men, with a lifetime prevalence of 0.3% in men.

Moreover, men who exhibit symptoms of anorexia may not meet the BMI criteria outlined in the DSM-IV due to having more muscle mass and therefore a higher bodyweight.[229] Consequently, a subclinical diagnosis, such as Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (ED-NOS) in the DSM-IV or Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED) in the DSM-5, is often made instead.[235]

Men with anorexia may also experience body dysmorphia, reporting their bodies to be twice as large than in actuality, and body dissatisfaction, especially with regard to muscularity and body composition. Men tend to place more emphasis on a muscular build as opposed to pursuing thinness.

Anorexic men are sometimes colloquially referred to as manorexic[238] or as having bigorexia.

Elderly

An increasing trend of anorexia among the elderly, termed "Anorexia of Aging,"[239] is observed, characterized by behaviors similar to those seen in typical anorexia nervosa but often accompanied by excessive laxative use.[239] Most geriatric anorexia patients limit their food intake to dairy or grains, whereas an adolescent anorexic has a more general limitation.[239]

This eating disorder that affects older adults has two types – early onset and late onset.[239] Early onset refers to a recurrence of anorexia in late life in an individual who experienced the disease during their youth.[239] Late onset describes instances where the eating disorder begins for the first time late in life.[239]

The stimulus for anorexia in elderly patients is typically a loss of control over their lives, which can be brought on by many events, including moving into an assisted living facility.[240] This is also a time when most older individuals experience a rise in conflict with family members, such as limitations on driving or limitations on personal freedom, which increases the likelihood of an issue with anorexia.[240] There can be physical issues in the elderly that leads to anorexia of aging, including a decline in chewing ability, a decline in taste and smell, and a decrease in appetite.[241] Psychological reasons for the elderly to develop anorexia can include depression and bereavement, and even an indirect attempt at suicide.[241] There are also common comorbid psychiatric conditions with aging anorexics, including major depression, anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and dementia.[242]

The signs and symptoms that go along with anorexia of aging are similar to what is observed in adolescent anorexia, including sudden weight loss, unexplained hair loss or dental problems, and a desire to eat alone.[240]

There are also several medical conditions that can result from anorexia in the elderly. An increased risk of illness and death can be a result of anorexia.[241] There is also a decline in muscle and bone mass as a result of a reduction in protein intake during anorexia.[241] Another result of anorexia in the aging population is irreparable damage to kidneys, heart or colon and an imbalance of electrolytes.[243]

Many assessments are available to diagnose anorexia in the aging community. These assessments include the Simplified Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire (SNAQ)[244] and Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Therapy (FAACT).[245][239] Specific to the geriatric populace, the interRAI system[246] identifies detrimental conditions in assisted living facilities and nursing homes.[239] Even a simple screening for nutritional insufficiencies such as low levels of important vitamins, can help to identify someone who has anorexia of aging.[239]

Anorexia in the elderly should be identified by the

The treatment for anorexia of aging is undifferentiated as anorexia for any other age group. Some of the treatment options include outpatient and inpatient facilities, antidepressant medication and behavioral therapy such as meal observation and discussing eating habits.[242]

History

The history of anorexia nervosa begins with descriptions of religious fasting dating from the

Etymologically, anorexia is a term of Greek origin: an- (ἀν-, prefix denoting negation) and orexis (ὄρεξις, "appetite"), translating literally to "a loss of appetite". In and of itself, this term does not have a harmful connotation, e.g., exercise-induced anorexia simply means that hunger is naturally suppressed during and after sufficiently intense exercise sessions.[250] It is the adjective nervosa that indicates the functional and non-organic nature of the disorder, but this adjective is also often omitted when the context is clear. Despite the literal translation of anorexia, the feeling of hunger in anorexia nervosa is frequently present and the pathological control of this instinct is a source of satisfaction for the patients.[251]

The term "anorexia nervosa" was coined in 1873 by

In the late 19th century anorexia nervosa became widely accepted by the medical profession as a recognized condition. Awareness of the condition was largely limited to the medical profession until the latter part of the 20th century, when German-American psychoanalyst Hilde Bruch published The Golden Cage: the Enigma of Anorexia Nervosa in 1978. Despite major advances in neuroscience,[255] Bruch's theories tend to dominate popular thinking. A further important event was the death of the popular singer and drummer Karen Carpenter in 1983, which prompted widespread ongoing media coverage of eating disorders.[256]

See also

- Body image

- Eating recovery

- Evolutionary psychiatry

- Idée fixe

- Inedia

- List of people with anorexia nervosa

- National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders

- Muscle dysmorphia

- Orthorexia nervosa

- Pro-ana

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "What are Eating Disorders?". NIMH. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ "Anorexia Nervosa". My.clevelandclinic.org. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ PMID 19719398.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ^ PMID 24277724.

- ISBN 978-0-7234-3461-0.

- ISBN 978-1-58562-462-1– via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Feeding and eating disorders" (PDF). American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ PMID 25678834.

- PMID 27733282.

- PMID 27733281.

- ^ S2CID 21580134.

- ^ S2CID 211728899.

- PMID 17284620.

- ^ "Force-Feeding of Anorexic Patients and the Right to Die" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ISSN 1359-1789.

- PMID 15212748.

- ISBN 978-0190926595.

- PMID 23658093.

- ^ PMID 23346610.

- PMID 30113325.

- ^ PMID 22644309.

- PMID 25530442.

- PMID 28846874.

- ^ a b "Anorexia nervosa - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 6 March 2025.

- ^ PMID 24999408.

- ^ PMID 20808514.

- ^ PMID 24011884.

- PMID 10940151.

- ISBN 978-0-323-02964-3. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "Anorexia Nervosa". National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- PMID 25834735.

- PMID 34421554.

- PMID 34068698.

- ISBN 978-0-07-803538-8.

- PMID 17497704.

- ^ Hedrick T (August 2022). "The Overlap Between Eating Disorders and Gastrointestinal Disorders" (PDF). Nutrition issues in Gastroenterology. University of Virginia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 February 2024.

- ^ S2CID 5417088.

Several case reports brought attention to the association of anorexia nervosa and celiac disease.(...) Some patients present with the eating disorder prior to diagnosis of celiac disease and others developed anorexia nervosa after the diagnosis of celiac disease. Healthcare professionals should screen for celiac disease with eating disorder symptoms especially with gastrointestinal symptoms, weight loss, or growth failure.(...) Celiac disease patients may present with gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, steatorrhea, weight loss, vomiting, abdominal pain, anorexia, constipation, bloating, and distension due to malabsorption. Extraintestinal presentations include anemia, osteoporosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, short stature, delayed puberty, fatigue, aphthous stomatitis, elevated transaminases, neurologic problems, or dental enamel hypoplasia.(...) it has become clear that symptomatic and diagnosed celiac disease is the tip of the iceberg; the remaining 90% or more of children are asymptomatic and undiagnosed.

- PMID 10940151.

- PMID 23429750.

- PMID 27425037.

- ^ "Anorexia nervosa". National Eating Disorders Collaboration (NEDC). 23 August 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ PMID 24200367.

- ISBN 978-0-470-01676-3.

- ISBN 978-0815382454.

- PMID 29884281.

- ^ S2CID 768206.

- ^ PMID 27504098.

- ^ .

- PMID 27556112.

- PMID 17610248.

- S2CID 6023688.

- ^ PMID 31313708.

- PMID 25101036.

- PMID 16231356.

- PMID 17607713.

- S2CID 216649851.

However, prospective studies are still scarce and the results from current literature regarding causal connections between AN and personality are unavailable.

- S2CID 36772859.

- ISBN 978-1-4200-3696-1.

- PMID 34895358.

- ISBN 978-1-135-44280-4.

- PMID 24199597.

- PMID 17676696.

- PMID 17958207.

- ISBN 978-1-4625-0790-0.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2014.

- PMID 23900859.

- PMID 39530423.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2010.

- ^ PMID 25206042.

- PMID 21243474.

- ISBN 978-0-19-993495-9.

- S2CID 37635456.

- S2CID 27183934.

- PMID 30353170.

- PMID 31308545.

- S2CID 210086516.

- PMID 28571669.

- S2CID 45181444.

- ISBN 978-0-387-92271-3.

- PMID 24106499.

- ^ S2CID 25805182. Archived from the original(PDF) on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- PMID 23674793.

- ^ PMID 23840288.

- PMID 34419970.

- PMID 33885180.

- PMID 16339438.

- S2CID 43620773.

- OCLC 84150452.

- ^ PMID 18164737.

- PMID 14599241.

- ^ Guisinger S. "Adapted to Famine: An Evolutionary Approach to Understanding Eating Behaviors". Archived from the original on 22 June 2024.

- PMID 38462152.

- PMID 8477269.

- ISBN 978-1-4822-9648-8.

- ISBN 978-0-941218-05-4.

- ISBN 978-0-19-105784-7.

- ISBN 978-1-118-32142-3.

- ^ a b "Factors That May Contribute to Eating Disorders". National Eating Disorders Association. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- PMID 11058477.

- PMID 12562569.

- ^ "Anorexia Nervosa". Mayo Clinic.

- S2CID 144731404.

- S2CID 10469356.

- PMID 35168670.

- PMID 22660896.

- ^ PMID 24365526.

- ^ PMID 21715295.

- ^ S2CID 205580678.

- PMID 15044128.

- S2CID 150323306

- ISBN 978-1-4625-3609-2.

- PMID 38770510.

- ISBN 978-0-471-23073-1.

- (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2015.

- PMID 17922532.

- S2CID 209342890.

- ^ "Eating Disorders Anorexia Causes | Eating Disorders". Psychiatric Disorders and Mental Health Issues. 13 June 2014. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- PMID 11896858.

- PMID 19030149.

- PMID 11927235.

- PMID 19030149.

- PMID 29651268.

- PMID 38770510.

- ISBN 9781138052550. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ S2CID 29355957.

- ^ PMID 8745105.

- S2CID 13036347.

- PMID 26388993.

- PMID 15732077.

- PMID 28301566.

- PMID 16721169.

- ^ S2CID 229325699.

- PMID 33336841.

- S2CID 25676759.

- S2CID 17250708.

- PMID 27725172.

- PMID 27933159.

- ISBN 978-3-642-15131-6.

- PMID 23570420.

- PMID 28967386.

- PMID 25902917.

- ^ S2CID 214769639.

- ^ "DSM-5 Changes: Implications for Child Serious Emotional Disturbance" (PDF). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. June 2016. p. 48 (Table 19, DSM-IV to DSM-5 Anorexia Nervosa Comparison). Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- PMID 25368605.

- PMID 19598270.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-89042-559-6, retrieved 17 December 2024

- PMID 21382223.

- PMID 38331700.

- ISBN 978-0-8261-7147-4. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- PMID 30765357.

- ^ a b c "Physical examination in Anorexia nervosa" (PDF).

- ^ "CBC blood test". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ "Comprehensive metabolic panel". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- S2CID 207361456.

- ^ "Guide to Common Laboratory Tests for Eating Disorder Patients" (PDF). Maudsleyparents.org. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- PMID 17610252.

- PMID 19424979.

- PMID 18521917.

- ^ "BUN – blood test". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 26 January 2012. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- PMID 10926180.

- PMID 12507163.

- PMID 21228564.

- ^ "Urinalysis". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 26 January 2012. Archived from the original on 4 April 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- PMID 22413702.

- ^ "Electroencephalogram". Medline Plus. 26 January 2012. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-803538-8.

- ^ PMID 26212713.

- ^ PMID 33099675.

- ^ PMID 19445758.

- ^ a b National Institute of Mental Health. "Eating disorders". Archived from the original on 23 March 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- PMID 3318754.

- S2CID 33438815.

- PMID 31041816.

- ^ PMID 19014864.

- ^ PMID 33351987.

- ^ "Eating Disorders". National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). 2011. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ISBN 978-1-85775-603-6. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-323-29352-5. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- PMID 25277720.

- S2CID 148977898.

- ISBN 978-1-259-06072-4.

- ISBN 978-1-57230-186-3.

- ISBN 978-1-133-58752-1. Archivedfrom the original on 24 November 2015.

- ^ PMID 26661289.

- PMID 9062520.

- ^ Garfinkel PE, Garner DM (1997). Handbook of Treatment for Eating Disorders. Guilford Press. pp. 156–157.

During the weekends in particular, some of the men found it difficult to stop eating. Their daily intake commonly ranged between 8,000 and 10,000 calories. [...] After about 5 months of refeeding, the majority of the men reported some normalization of their eating patterns, but for some the extreme overconsumption persisted. [...] More than 8 months after renourishment began, most men had returned to normal eating patterns; however, a few were still eating abnormal amounts.

- ISBN 978-0-323-03004-5. Archived from the originalon 21 January 2024.

Hypophosphatemia is considered the hallmark of refeeding syndrome, although other imbalances may occur as well, including hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia.

- PMID 23459608.

- ^ "Nutrition support for adults: oral nutrition support, enteral tube feeding and parenteral nutrition". NICE. 4 August 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ PMID 25565909.

- PMID 16437485.

- S2CID 208957067.

- ^ Staff ED (2 April 2017). "Common Medication Treatments for Anorexia: An Overview". Eating Disorder Hope. Retrieved 6 March 2025.

- PMID 21727255.

- .

- ^ MARSIPAN Working Group (2014). "CR189: Management of Really Sick Patients with Anorexia Nervosa" (Second ed.). Royal College of Psychiatrists. p. 6. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016.

- ^ PMID 33092638.

- ^ doi: 10.1192/bjo.2018.78

- ^ S2CID 209894802.

- PMID 22609034.

- ISBN 978-0-07-803538-8.

- PMID 32181530.

- ^ Leigh S (19 November 2019). "Many Patients with Anorexia Nervosa Get Better, But Complete Recovery Elusive to Most". University of California San Francisco. The Regents of The University of California. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- PMID 26166318.

- PMID 36937727.

- ^ "Core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders" (PDF). National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2014.

- S2CID 42042720.

- S2CID 39940665.

- ^ PMID 17389700.

- PMID 24898127.

- ISBN 978-1-55009-364-3. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ PMID 26407541.

- ^ Gibson D (12 December 2024). "The Effects of Purging on Oral Health". ACUTE Center for Eating Disorders & Severe Malnutrition. Retrieved 12 February 2025.

- ^ "FACT SHEET: Eating Disorders". College of Dental Hygienists of Ontario. Archived from the original on 13 February 2025. Retrieved 12 February 2025.

- ^ PMID 26710932.

- ^ PMID 3335466.

- PMID 3460535.

- ^ PMID 35629258.

- ^ PMID 22135615.

- PMID 19107833.

- PMID 38217553.

- S2CID 29156560.

- ISBN 978-3-642-29135-7.

- PMID 31694978.

- PMID 15520673.

- S2CID 41396054.

- ^ PMID 18335017.

- S2CID 10232724.

- PMID 15379177.

- ^ "Male Anorexia: Understanding Eating Disorders in Men and Boys". Psych Central. 20 May 2022. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- PMID 19107833.

- ISSN 0924-9338.

- PMID 19379023.

- PMID 30637488.

- PMID 22985234.

- ISBN 978-1-84850-906-1. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ PMID 26828516.

- ^ a b c d Ekern B (25 February 2016). "Common Types of Eating Disorders Observed in the Elderly Population". Eating Disorder Hope. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ PMID 23658838.

- ^ S2CID 38114971.

- ^ S2CID 3099767.

- PMID 32967354.

- ^ "Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Treatment (FAACT)". FACIT.org.

- PMID 24007312.

- ^ S2CID 30482453.

- PMID 23545792.

- PMID 25372187.

- PMID 7835326.

Subjective feelings of hunger were significantly suppressed during and after intense exercise sessions (P 0.01), but the suppression was short-lived.

- PMID 15204807.

- PMID 9385628.

- ^ Gull WW (1894). Acland TD (ed.). Medical Papers. p. 309.

- PMID 9385627.

- ISBN 978-0-415-89867-6.

- ^ Arnold C (29 March 2016). "Anorexia: you don't just grow out of it". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

Further reading

- Bailey AP, Parker AG, Colautti LA, Hart LM, Liu P, Hetrick SE (2014). "Mapping the evidence for the prevention and treatment of eating disorders in young people". Journal of Eating Disorders. 2 (1): 5. PMID 24999427.

- Coelho GM, Gomes AI, Ribeiro BG, Soares E (2014). "Prevention of eating disorders in female athletes". Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine. 5: 105–113. PMID 24891817.

- Luca A, Luca M, Calandra C (February 2015). "Eating Disorders in Late-life". Aging and Disease. 6 (1): 48–55. PMID 25657852.