Molière

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) |

Molière | |

|---|---|

The Learned Ladies | |

| Spouse | Armande Béjart |

| Partner | Madeleine Béjart |

| Children | Louis (1664–1664) Marie Madeleine (1665–1723) Pierre (1672–1672) |

| Signature | |

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (French pronunciation:

Born into a prosperous family and having studied at the Collège de Clermont (now Lycée Louis-le-Grand), Molière was well suited to begin a life in the theatre. Thirteen years as an itinerant actor helped him polish his comedic abilities while he began writing, combining Commedia dell'arte elements with the more refined French comedy.[6]

Through the patronage of aristocrats including

Despite the adulation of the court and Parisians, Molière's satires attracted criticism from other circles. For Tartuffe's impiety, the Catholic Church in France denounced this study of religious hypocrisy, which was followed by a ban by the Parlement, while Dom Juan was withdrawn and never restaged by Molière.[8] His hard work in so many theatrical capacities took its toll on his health and, by 1667, he was forced to take a break from the stage. In 1673, during a production of his final play, The Imaginary Invalid, Molière, who suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis, was seized by a coughing fit and a haemorrhage while playing the hypochondriac Argan; he finished the performance but collapsed again and died a few hours later.[7]

Life

Molière was born in Paris shortly before his christening as Jean Poquelin on 15 January 1622. Known as Jean-Baptiste, he was the first son of Jean Poquelin and Marie Cressé, who had married on 27 April 1621.

In 1631, his father Jean Poquelin purchased from the court of Louis XIII the posts of "valet de chambre ordinaire et tapissier du Roi" ("valet of the King's chamber and keeper of carpets and upholstery"). His son assumed the same posts in 1641.[15] The title required only three months' work and an initial cost of 1,200 livres; the title paid 300 livres a year and provided a number of lucrative contracts. Molière also studied as a provincial lawyer some time around 1642, probably in Orléans, but it is not documented that he ever qualified. So far he had followed his father's plans, which had served him well; he had mingled with nobility at the Collège de Clermont and seemed destined for a career in office.

In June 1643, when Molière was 21, he decided to abandon his social class and pursue a career on the stage. Taking leave of his father, he joined the actress Madeleine Béjart, with whom he had crossed paths before, and founded the Illustre Théâtre with 630 livres. They were later joined by Madeleine's brother and sister.

The theatre troupe went bankrupt in 1645. Molière had become head of the troupe, due in part, perhaps, to his acting prowess and his legal training. However, the troupe had acquired large debts, mostly for the rent of the theatre (a court for

After his imprisonment, he and Madeleine began a theatrical circuit of the provinces with a new

In

Return to Paris

Molière was forced to reach Paris in stages, staying outside for a few weeks in order to promote himself with society gentlemen and allow his reputation to feed in to Paris. Molière reached Paris in 1658 and performed in front of the King at the

Les Précieuses Ridicules was the first of Molière's many attempts to satirize certain societal mannerisms and affectations then common in France. It is widely accepted that the plot was based on Samuel Chappuzeau's Le Cercle des Femmes of 1656. He primarily mocks the Académie Française, a group created by Richelieu under a royal patent to establish the rules of the fledgling French theatre. The Académie preached unity of time, action, and styles of verse. Molière is often associated with the claim that comedy castigat ridendo mores or "criticises customs through humour" (a phrase in fact coined by his contemporary Jean de Santeuil and sometimes mistaken for a classical Latin proverb).[16]

Height of fame

Despite his own preference for tragedy, which he had tried to further with the Illustre Théâtre, Molière became famous for his farces, which were generally in one act and performed after the tragedy. Some of these farces were only partly written, and were played in the style of Commedia dell'arte with improvisation over a canovaccio (a vague plot outline). He began to write full, five-act comedies in verse (L'Étourdi (Lyon, 1654) and Le dépit amoureux (Béziers, 1656)), which although immersed in the gags of contemporary Italian troupes, were successful as part of Madeleine Béjart and Molière's plans to win aristocratic patronage and, ultimately, move the troupe to a position in a Paris theater-venue.[17] Later Molière concentrated on writing musical comedies, in which the drama is interrupted by songs and/or dances, but for years the fundamentals of numerous comedy-traditions would remain strong, especially Italian (e.g. the semi-improvisatory style that in the 1750s writers started calling commedia dell'arte), Spanish, and French plays, all also drawing on classical models (e.g. Plautus and Terence), especially the trope of the clever slave/servant.[18][19]

Les précieuses ridicules won Molière the attention and the criticism of many, but it was not a popular success. He then asked Fiorillo to teach him the techniques of Commedia dell'arte. His 1660 play Sganarelle, ou Le Cocu imaginaire (The Imaginary Cuckold) seems to be a tribute both to Commedia dell'arte and to his teacher. Its theme of marital relationships dramatizes Molière's pessimistic views on the falsity inherent in human relationships. This view is also evident in his later works and was a source of inspiration for many later authors, including (in a different field and with different effect) Luigi Pirandello. It describes a kind of round dance where two couples believe that each of their partners has been betrayed by the other's and is the first in Molière's "Jealousy series", which includes Dom Garcie de Navarre, L'École des maris and L'École des femmes.

In 1660 the Petit-Bourbon was demolished to make way for the eastern expansion of the Louvre, but Molière's company was allowed to move into the abandoned theatre in the east wing of the Palais-Royal. After a period of refurbishment they opened there on 20 January 1661. In order to please his patron, Monsieur, who was so enthralled with entertainment and art that he was soon excluded from state affairs, Molière wrote and played Dom Garcie de Navarre ou Le Prince jaloux (The Jealous Prince, 4 February 1661), a heroic comedy derived from a work of Cicognini's. Two other comedies of the same year were the successful L'École des maris (The School for Husbands) and Les Fâcheux (The Bores), subtitled Comédie faite pour les divertissements du Roi (a comedy for the King's amusements) because it was performed during a series of parties that Nicolas Fouquet gave in honor of the sovereign. These entertainments led Jean-Baptiste Colbert to demand the arrest of Fouquet for wasting public money, and he was condemned to life imprisonment.[20]

On 20 February 1662, Molière married

However, more serious opposition was brewing, focusing on Molière's politics and his personal life. A so-called parti des Dévots arose in French high society, who protested against Molière's excessive "

Molière's friendship with Jean-Baptiste Lully influenced him towards writing his Le Mariage forcé and La Princesse d'Élide (subtitled as Comédie galante mêlée de musique et d'entrées de ballet), written for royal "divertissements" at the Palace of Versailles.

Tartuffe, ou L'Imposteur was also performed at Versailles, in 1664, and created the greatest scandal of Molière's artistic career. Its depiction of the hypocrisy of the dominant classes was taken as an outrage and violently contested. It also aroused the wrath of the Jansenists and the play was banned.

Molière was always careful not to attack the institution of monarchy. He earned a position as one of the king's favourites and enjoyed his protection from the attacks of the court. The king allegedly suggested that Molière suspend performances of Tartuffe, and the author rapidly wrote Dom Juan ou le Festin de Pierre to replace it. It was a strange work, derived from a work by Tirso de Molina and rendered in a prose that still seems modern today. It describes the story of an atheist who becomes a religious hypocrite and, for this, is punished by God. This work too was quickly suspended. The king, demonstrating his protection once again, became the new official sponsor of Molière's troupe.

With music by Lully, Molière presented L'Amour médecin (Love Doctor or Medical Love). Subtitles on this occasion reported that the work was given "par ordre du Roi" (by order of the king) and this work was received much more warmly than its predecessors.

In 1666,

After the Mélicerte and the Pastorale comique, he tried again to perform a revised Tartuffe in 1667, this time with the name of Panulphe or L'Imposteur. As soon as the King left Paris for a tour, Lamoignon and the archbishop banned the play. The King finally imposed respect for Tartuffe a few years later, after he had gained more power over the clergy.

Molière, now ill, wrote less. Le Sicilien ou L'Amour peintre was written for festivities at the

With Lully he again used music for Monsieur de Pourceaugnac, for Les Amants magnifiques, and finally for Le Bourgeois gentilhomme (The Middle Class Gentleman), another of his masterpieces. It is claimed to be particularly directed against Colbert, the minister who had condemned his old patron Fouquet. The collaboration with Lully ended with a tragédie et ballet, Psyché, written in collaboration with Pierre Corneille and Philippe Quinault.

In 1672, Madeleine Béjart died, and Molière suffered from this loss and from the worsening of his own illness. Nevertheless, he wrote a successful

Les Femmes savantes (

In his 14 years in Paris, Molière singlehandedly wrote 31 of the 85 plays performed on his stage.

Les Comédies-Ballets

In 1661, Molière introduced the

Death

Molière suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis, possibly contracted when he was imprisoned for debt as a young man. The circumstances of Molière's death, on 17 February 1673,

Under French law at the time, actors were not allowed to be buried in the sacred ground of a cemetery. However, Molière's widow, Armande, asked the King if her spouse could be granted a normal funeral at night. The King agreed and Molière's body was buried in the part of the cemetery reserved for unbaptised infants.

In 1792, his remains were brought to the museum of French monuments, and in 1817, transferred to Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, close to those of La Fontaine.

Reception of his works

Though conventional thinkers, religious leaders and medical professionals in Molière's time criticised his work, their ideas did not really diminish his widespread success with the public. Other playwrights and companies began to emulate his dramatic style in England and in France. Molière's works continued to garner positive feedback in 18th-century England, but they were not so warmly welcomed in France at this time. However, during the French Restoration of the 19th century, Molière's comedies became popular with both the French public and the critics. Romanticists admired his plays for the unconventional individualism they portrayed. 20th-century scholars have carried on this interest in Molière and his plays and have continued to study a wide array of issues relating to this playwright. Many critics now are shifting their attention from the philosophical, religious and moral implications in his comedies to the study of his comic technique.[26]

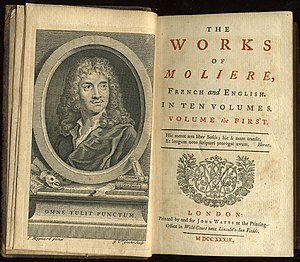

Molière's works were translated into English prose by John Ozell in 1714,[27] but the first complete version in English, by Baker and Miller in 1739, remained "influential" and was long reprinted.[28] The first to offer full translations of Molière's verse plays such as Tartuffe into English verse was Curtis Hidden Page, who produced blank verse versions of three of the plays in his 1908 translation.[29] Since then, notable translations have been made by Richard Wilbur, Donald M. Frame, and many others.

In his memoir A Terrible Liar, actor Hume Cronyn writes that, in 1962, celebrated actor Laurence Olivier criticized Molière. According to Cronyn, he mentioned to Olivier that he (Cronyn) was about to play the title role in The Miser, and that Olivier then responded "Molière? Funny as a baby's open grave." Cronyn comments on the incident: "You may imagine how that made me feel. Fortunately, he was dead wrong."[30]

Author Martha Bellinger points out that:

[Molière] has been accused of not having a consistent, organic style, of using faulty grammar, of mixing his metaphors, and of using unnecessary words for the purpose of filling out his lines. All these things are occasionally true, but they are trifles in comparison to the wealth of character he portrayed, to his brilliancy of wit, and to the resourcefulness of his technique. He was wary of sensibility or pathos; but in place of pathos he had "melancholy — a puissant and searching melancholy, which strangely sustains his inexhaustible mirth and his triumphant gaiety".[31]

Influence on French culture

Molière is considered the creator of modern French comedy. Many words or phrases introduced in Molière's plays are still used in current French:

- A tartuffe is a hypocrite, especially a hypocrite displaying affected morality or religious piety.

- A harpagon, named after the main character of The Miser, is an obsessively greedy and cheap man.

- The statue of the Commander (statue du Commandeur) from Dom Juan is used as a model of implacable rigidity (raide comme la statue du Commandeur).

- In Les Fourberies de Scapin, Act II, scene 7, Géronte is asked for ransom money for his son, allegedly held in a galley. He repeats, "What the deuce did he want to go into that galley for?" (Que diable allait-il faire dans cette galère?) The phrase "to go into that galley" is used to describe unnecessary difficulties a person has sought, and galère ("galley") means a difficult and chaotic situation.

- In Tartuffe, act 3, scene 2, Tartuffe insists that Dorine take a handkerchief to cover up her bosom, saying, "Cover that bosom which I ought not to see" (Couvrez ce sein que je ne saurais voir). This phrase (often with cachez, "hide," instead of couvrez, and often with some other item replacing sein) is frequently used to imply that someone else is calling for something to be hidden or ignored out of their own hypocrisy, disingenuousness, censoriousness, etc.

- In dog latinand recursive explanations which conclude with an authoritative "and so that is why your daughter is mute" (Et voilà pourquoi votre fille est muette). The phrase is used wholesale to mock an unsatisfactory explanation.

- Monsieur Jourdain in Le Bourgeois gentilhomme arranges to be tutored in good manners and culture, and is delighted to learn that, because every statement that is not poetry is prose, he therefore has been speaking prose for 40 years without knowing it (Par ma foi, il y a plus de quarante ans que je dis de la prose, sans que j’en susse rien). The more modern phrase "je parle de la prose sans le savoir" is used by a person who realizes that he was more skilled or better aligned than he thought.

- In the Comédie-ballet "George Dandin" (1668), Act I, scene 7, the main character uses the phrase Tu l'as voulu, George Dandin ("You wanted it, George Dandin") to address himself when his rich wife cheats on him. Now the phrase is used to reproach someone ironically, something like "You did it yourself".

Portrayals of Molière

Molière plays a small part in

Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov wrote a semi-fictitious biography-tribute to Molière, titled Life of Mr. de Molière. It was written in 1932–1933 and first published 1962.

The French 1978 film simply titled Molière directed by Ariane Mnouchkine and starring Philippe Caubère presents his complete biography. It was in competition for the Palme d'Or at Cannes in 1978.

He is portrayed among other writers in The Blasphemers' Banquet (1989).

The 2000 film

The 2007 French film Molière was more loosely based on the life of Molière, starring Romain Duris, Fabrice Luchini and Ludivine Sagnier.

David Hirson's play La Bête, written in the style of Molière, includes the character Elomire as an anagrammatic parody of him.

The 2023 musical Molière, l'Opéra Urbain, directed by Bruno Berberes and staged at the Dôme de Paris from November 11, 2023 to February 18, 2024, is a retelling of the life of Molière using a blend of historical costuming with contemporary artistic styles in staging and musical genres. [32]

List of major works

- Le Médecin volant (1645)—The Flying Doctor

- La Jalousie du barbouillé (1650)—The Jealousy of le Barbouillé

- L'Étourdi ou les Contretemps (1655)—The Blunderer, or, the Counterplots

- Le Dépit amoureux (16 December 1656)—The Love-Tiff

- Le Docteur amoureux (1658), the first play performed by Molière's troupe for Louis XIV(now lost)—The Doctor in Love

- Les Précieuses ridicules (18 November 1659)—The Affected Young Ladies

- Sganarelle ou Le Cocu imaginaire (28 May 1660)—Sganarelle, or the Imaginary Cuckold

- Dom Garcie de Navarre ou Le Prince jaloux (4 February 1661)—Don Garcia of Navarre or the Jealous Prince

- L'École des maris (24 June 1661)—The School for Husbands

- Les Fâcheux (17 August 1661)—The Bores (also translated The Mad)

- L'École des femmes (26 December 1662; adapted into The Amorous Flea, 1964)—The School for Wives

- La Jalousie du Gros-René (15 April 1663; now lost)—The Jealousy of Gros-René

- La Critique de l'école des femmes (1 June 1663)—Critique of the School for Wives

- L'Impromptu de Versailles (14 October 1663)—The Versailles Impromptu

- Le Mariage forcé (29 January 1664)—The Forced Marriage

- Gros-René, petit enfant (27 April 1664; now lost)—Gros-René, Small Child

- La Princesse d'Élide (8 May 1664)—The Princess of Elid

- Tartuffe ou L'Imposteur (12 May 1664)—Tartuffe, or, the Impostor

- Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre (15 February 1665)—Don Juan, or, The Stone Banquet (subtitle also translated The Stone Guest, The Feast with the Statue, &c.)

- L'Amour médecin (15 September 1665)—Love Is the Doctor

- Le Misanthrope ou L'Atrabilaire amoureux(4 June 1666)—The Misanthrope, or, the Cantankerous Lover

- Le Médecin malgré lui (6 August 1666)—The Doctor in Spite of Himself

- Mélicerte (2 December 1666)

- Pastorale comique (5 January 1667)—Comic Pastoral

- Le Sicilien ou L'Amour peintre (14 February 1667)—The Sicilian, or Love the Painter

- Amphitryon(13 January 1668)

- George Dandin ou Le Mari confondu(18 July 1668)—George Dandin, or the Abashed Husband

- L'Avare ou L'École du mensonge(9 September 1668)—The Miser, or, the School for Lies

- Monsieur de Pourceaugnac (6 October 1669)

- Les Amants magnifiques (4 February 1670)—The Magnificent Lovers

- Le Bourgeois gentilhomme (14 October 1670)—The Bourgeois Gentleman

- Psyché (17 January 1671)—Psyche

- Les Fourberies de Scapin(24 May 1671)—The Impostures of Scapin

- La Comtesse d'Escarbagnas (2 December 1671)—The Countess of Escarbagnas

- Les Femmes savantes(11 March 1672)—The Learned Ladies

- Le Malade imaginaire (10 February 1673)—The Imaginary Invalid (or The Hypochondriac)[33]

References

- ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ "Molière". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Hartnoll, p. 554. "Author of some of the finest comedies in the history of the theater", and Roy, p. 756. "...one of the theatre's greatest comic artists".

- ^ Randall, Colin (24 October 2004). "France looks to the law to save the language of Molière" – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ Roy, p. 756.

- ^ a b Roy, p. 756–757.

- ISBN 9780521434379.

- ^ Gaines 2002, p. 383 (birthdate); Scott 2000, p. 14 (names).

- ^ Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft (1840). Lives of the Most Eminent French Writers. Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard. p. 116.

lives of the most eminent french writers.

- ISBN 978-0-205-51186-0.

- ^ Marie Cressé died on 11 May 1632 (Gaines 2002, p. xi).

- ^ Scott 2000, p. 16.

- ^ O'Malley, John W. (2014). The Jesuits; a history from Ignatius to the present. London: Sheed and Ward. p. 30.

- ISBN 273770054X.

- ^ Martin Barnham. "The Cambridge Guide to Theater." Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1995, p. 472.

- ^ On L'Étourdi and his theatrical accomplishments in this and other early plays, see e.g. Stephen C. Bold, “‘Ce Noeud Subtil’: Molière’s Invention of Comedy from L’Étourdi to ‘'Les Fourberies de Scapin ", " The Romanic Review 88/1(1997): 67-85; David Maskell, Moliere's L'Etourdi: Signs of Things to Come", French Studies 46/1 (1992): 13-25; and Philip A. Wadsworth, "Scappino & Mascarille," in Molière and the Comedy of Intellect (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1962), 1-7.

- ISBN 1683931297

- ISBN 9780917786709

- ^ Jacob Soll, The Information Master: Jean-Baptiste Colbert's Secret State Intelligence System (Ann Arbor: Univ. of MI Press, 2009), 43-52.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-500-20352-1.

- ISBN 978-0-500-20352-1.

- ISBN 978-0-500-20352-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-500-20352-1.

- ^ "Molière - French dramatist". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- Enotes.com.

- G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 43. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ISBN 9781884964367. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 31. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ISBN 9780688128449. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- Henry Holt & Company. pp. 178–81. Retrieved November 27, 2007 – via Theatredatabase.com.

- ^ De Sortiraparis, Julie (November 17, 2023). "Molière l'opéra urbain, the extraordinary musical comedy about Molière at the Dôme de Paris". Sortiraparis.com. Retrieved Tuesday, December 12, 2023.

- ^ "The Imaginary Invalid". The Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

Bibliography

- Alberge, Claude (1988). Voyage de Molière en Languedoc (1647–1657). Montpellier: Presses du Languedoc. ISBN 9782859980474.

- Dormandy, Thomas (2000). The White Death: A History of Tuberculosis. New York University Press, p. 10. ISBN 9780814719275.

- Gaines, James F., editor (2002). The Molière Encyclopedia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313312557.

- Hartnoll, Phyllis, editor (1983). The Oxford Companion to the Theatre (fourth edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192115461.

- Ranum, Patricia M. (2004). Portraits around Marc-Antoine Charpentier. Baltimore: Patricia M. Ranum. "Molière", pp. 141–49. ISBN 9780966099737.

- Riggs, Larry (2005). Molière and Modernity, Charlottesville: Rookwood Press. ISBN 9781886365551.

- Roy, Donald (1995). "Molière", pp. 756–757, in The Cambridge Guide to Theatre, edited by Martin Banham. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521434379.

- Scott, Virginia (2000). Molière, A Theatrical Life. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780192115461.

External links

- Works by Molière in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Molière at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Molière at Internet Archive

- Works by Molière at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Molière's works online Archived 2020-09-06 at the Wayback Machine at toutmoliere.net (in French)

- Molière's works online at site-Molière.com

- Molière's works online at InLibroVeritas.net

- "Biography, Bibliography, Analysis, Plot overview" (in French). biblioweb.org. Archived from the original on 2006-01-14.

- Moliere's Verses Plays Publication, Statistics, Words Research (in French)

- The Comédie Française Registers a database of over 34,000 performances from 1680 to 1791

- Free Online 2010 American Translation of Dom Juan ou le Festin de pierre

- Free Online 2011 American Translation of Le Médecin malgré lui

- Free Online 2012 American Translation of Les Fourberies de Scapin