Syphilis

| Syphilis | |

|---|---|

Antibiotics[4] | |

| Frequency | 45.4 million / 0.6% (2015, global)[5] |

| Deaths | 107,000 (2015, global)[6] |

Syphilis (

Syphilis is most commonly spread through

The risk of sexual transmission of syphilis can be reduced by using a

In 2015, about 45.4 million people had syphilis infections,[5] of which six million were new cases.[9] During 2015, it caused about 107,000 deaths, down from 202,000 in 1990.[6][10] After decreasing dramatically with the availability of penicillin in the 1940s, rates of infection have increased since the turn of the millennium in many countries, often in combination with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).[3][11] This is believed to be partly due to unsafe drug use, increased prostitution, and decreased use of condoms.[12][13][14]

Signs and symptoms

Syphilis can

Primary

Primary syphilis is typically acquired by direct sexual contact with the infectious lesions of another person.

Secondary

Secondary syphilis occurs approximately four to ten weeks after the primary infection.

Latent

Latent syphilis is defined as having serologic proof of infection without symptoms of disease.[19] It develops after secondary syphilis and is divided into early latent and late latent stages.[27] Early latent syphilis is defined by the World Health Organization as less than 2 years after original infection.[27] Early latent syphilis is infectious as up to 25% of people can develop a recurrent secondary infection (during which bacteria are actively replicating and are infectious).[27] Two years after the original infection the person will enter late latent syphilis and is not as infectious as the early phase.[25][28] The latent phase of syphilis can last many years after which, without treatment, approximately 15–40% of people can develop tertiary syphilis.[29]

Tertiary

Tertiary syphilis may occur approximately 3 to 15 years after the initial infection and may be divided into three different forms: gummatous syphilis (15%), late neurosyphilis (6.5%), and cardiovascular syphilis (10%).[3][25] Without treatment, a third of infected people develop tertiary disease.[25] People with tertiary syphilis are not infectious.[3]

Gummatous syphilis or late

Cardiovascular syphilis usually occurs 10–30 years after the initial infection.[3] The most common complication is syphilitic aortitis, which may result in aortic aneurysm formation.[3]

Meningovascular syphilis involves inflammation of the small and medium arteries of the central nervous system. It can present between 1–10 years after the initial infection. Meningovascular syphilis is characterized by stroke, cranial nerve palsies and

Congenital

Congenital syphilis is that which is transmitted during pregnancy or during birth.

Cause

Bacteriology

Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum is a spiral-shaped,

Transmission

Syphilis is transmitted primarily by sexual contact or during

It is not generally possible to contract syphilis through toilet seats, daily activities, hot tubs, or sharing eating utensils or clothing.[38] This is mainly because the bacteria die very quickly outside of the body, making transmission by objects extremely difficult.[39]

Diagnosis

Syphilis is difficult to diagnose clinically during early infection.

Blood tests

Blood tests are divided into nontreponemal and treponemal tests.[22]

Nontreponemal tests are used initially and include

Because of the possibility of false positives with nontreponemal tests, confirmation is required with a treponemal test, such as

Direct testing

Prevention

Vaccine

As of 2018[update], there is no

Sex

Condom use reduces the likelihood of transmission during sex, but does not eliminate the risk.[46] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states, "Correct and consistent use of latex condoms can reduce the risk of syphilis only when the infected area or site of potential exposure is protected.[47] However, a syphilis sore outside of the area covered by a latex condom can still allow transmission, so caution should be exercised even when using a condom."[48]

Congenital disease

Congenital syphilis in the newborn can be prevented by screening mothers during early pregnancy and treating those who are infected.

Screening

The CDC recommends that sexually active men who have sex with men be tested at least yearly.[56] The USPSTF also recommends screening among those at high risk.[57]

Syphilis is a notifiable disease in many countries, including Canada,[58] the European Union,[59] and the United States.[60] This means health care providers are required to notify public health authorities, which will then ideally provide partner notification to the person's partners.[61] Physicians may also encourage patients to send their partners to seek care.[62] Several strategies have been found to improve follow-up for STI testing, including email and text messaging of reminders for appointments.[63]

Treatment

Historic use of mercury

As a form of

Early infections

The first-line treatment for uncomplicated syphilis (primary or secondary stages) remains a single dose of

Late infections

For neurosyphilis, due to the poor penetration of benzathine penicillin into the

Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction

One of the potential side effects of treatment is the Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction.[3] It frequently starts within one hour and lasts for 24 hours, with symptoms of fever, muscle pains, headache, and a fast heart rate.[3] It is results from the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines by the immune system in response to lipoproteins released from rupturing syphilis bacteria.[72]

Pregnancy

Penicillin is an effective treatment for syphilis in pregnancy[73] but there is no agreement on which dose or route of delivery is most effective.[74]

Epidemiology

| no data <35 35–70 70–105 105–140 140–175 175–210 | 210–245 245–280 280–315 315–350 350–500 >500 |

In 2012, about 0.5% of adults were infected with syphilis, with 6 million new cases.

Syphilis was very common in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries.[11] Flaubert found it universal among 19th-century Egyptian prostitutes.[81] In the developed world during the early 20th century, infections declined rapidly with the widespread use of antibiotics, until the 1980s and 1990s.[11] Since 2000, rates of syphilis have been increasing in the US, Canada, the UK, Australia and Europe, primarily among men who have sex with men.[34] Rates of syphilis among US women have remained stable during this time, while rates among UK women have increased, but at a rate less than that of men.[82] Increased rates among heterosexuals have occurred in China and Russia since the 1990s.[34] This has been attributed to unsafe sexual practices, such as sexual promiscuity, prostitution, and decreasing use of barrier protection.[34][82][83]

Left untreated, it has a mortality rate of 8% to 58%, with a greater death rate among males.[3] The symptoms of syphilis have become less severe over the 19th and 20th centuries, in part due to widespread availability of effective treatment, and partly due to virulence of the bacteria.[23] With early treatment, few complications result.[22] Syphilis increases the risk of HIV transmission by two to five times, and coinfection is common (30–60% in some urban centers).[3][34] In 2015, Cuba became the first country to eliminate mother-to-child transmission of syphilis.[84]

History

Origin, spread and discovery

Paleopathologists have known for decades that syphilis was present in the Americas before European contact.[86][87] The situation in Afro-Eurasia has been murkier and caused considerable debate.[88] According to the Columbian theory, syphilis was brought to Spain by the men who sailed with Christopher Columbus in 1492 and spread from there, with a serious epidemic in Naples beginning as early as 1495. Contemporaries believed the disease sprang from American roots, and in the 16th century physicians wrote extensively about the new disease inflicted on them by the returning explorers.[89]

Most evidence supports the Columbian origin hypothesis.[90] However, beginning in the 1960s, examples of probable treponematosis—the parent disease of syphilis, bejel, and yaws—in skeletal remains shifted the opinion of some towards a "pre-Columbian" origin.[91][92] A 2024 study published in Nature supported an emergence postdating human occupation in the Americas.[93]

When living conditions changed with urbanization, elite social groups began to practice basic hygiene and started to separate themselves from other social tiers. Consequently, treponematosis was driven out of the age group in which it had become endemic. It then began to appear in adults as syphilis. Because they had never been exposed as children, they were not able to fend off serious illness. Spreading the disease via sexual contact also led to victims being infected with a massive bacterial load from open sores on the genitalia. Adults in higher socioeconomic groups then became very sick with painful and debilitating symptoms lasting for decades. Often, they died of the disease, as did their children who were infected with congenital syphilis. The difference between rural and urban populations was first noted by Ellis Herndon Hudson, a clinician who published extensively about the prevalence of treponematosis, including syphilis, in times past.[94] The importance of bacterial load was first noted by the physician Ernest Grin in 1952 in his study of syphilis in Bosnia.[95]

The most compelling evidence for the validity of the pre-Columbian hypothesis is the presence of syphilitic-like damage to bones and teeth in medieval skeletal remains. While the absolute number of cases is not large, new ones are continually discovered, most recently in 2015.[96] At least fifteen cases of acquired treponematosis based on evidence from bones, and six examples of congenital treponematosis based on evidence from teeth, are now widely accepted. In several of the twenty-one cases the evidence may also indicate syphilis.[97]

In 2020, a group of leading paleopathologists concluded that enough evidence had been collected to prove that treponemal disease, almost certainly including syphilis, had existed in Europe prior to the voyages of Columbus.[98] There is an outstanding issue, however. Damaged teeth and bones may seem to hold proof of pre-Columbian syphilis, but there is a possibility that they point to an endemic form of treponemal disease instead. As syphilis, bejel, and yaws vary considerably in mortality rates and the level of human disease they elicit, it is important to know which one is under discussion in any given case, but it remains difficult for paleopathologists to distinguish among them. (The fourth of the treponemal diseases is pinta, a skin disease and therefore unrecoverable through paleopathology.) Ancient DNA (aDNA) holds the answer, because just as only aDNA suffices to distinguish between syphilis and other diseases that produce similar symptoms in the body, it alone can differentiate spirochetes that are 99.8 percent identical with absolute accuracy.[99] Progress on uncovering the historical extent of syndromes through aDNA remains slow, however, because the bacterium responsible for treponematosis is rare in skeletal remains and fragile, making it notoriously difficult to recover and analyse. Precise dating to the medieval period is not yet possible but work by Kettu Majander et al. uncovering the presence of several different kinds of treponematosis at the beginning of the early modern period argues against its recent introduction from elsewhere. Therefore, they argue, treponematosis—possibly including syphilis—almost certainly existed in medieval Europe.[100]

Despite significant progress in tracing the presence of syphilis in past historic periods, definitive findings from paleopathology and aDNA studies are still lacking for the medieval period. Evidence from art is therefore helpful in settling the issue. Research by Marylynn Salmon has demonstrated that deformities in medieval subjects can be identified by comparing them to those of modern victims of syphilis in medical drawings and photographs.[101] One of the most typical deformities, for example, is a collapsed nasal bridge called saddle nose. Salmon discovered that it appeared often in medieval illuminations, especially among the men tormenting Christ in scenes of the crucifixion. The association of saddle nose with evil is an indication that the artists were thinking of syphilis, which is typically transmitted through sexual intercourse with promiscuous partners, a mortal sin in medieval times.

It remains mysterious why the authors of medieval medical treatises so uniformly refrained from describing syphilis or commenting on its existence in the population. Many may have confused it with other diseases such as leprosy (Hansen's disease) or elephantiasis. The great variety of symptoms of treponematosis, the different ages at which the various diseases appear, and its widely divergent outcomes depending on climate and culture, would have added greatly to the confusion of medical practitioners, as indeed they did right down to the middle of the 20th century. In addition, evidence indicates that some writers on disease feared the political implications of discussing a condition more fatal to elites than to commoners. Historian Jon Arrizabalaga has investigated this question for Castile with startling results revealing an effort to hide its association with elites.[102]

The first written records of an outbreak of syphilis in Europe occurred in 1495 in

In the 16th through 19th centuries, syphilis was one of the largest public health burdens in

The causative organism, Treponema pallidum, was first identified by

During the 20th century, as both

Many famous historical figures, including

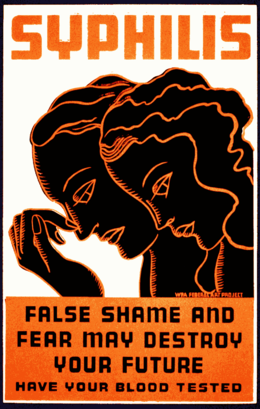

Arts and literature

The earliest known depiction of an individual with syphilis is

The Flemish artist Stradanus designed a print called Preparation and Use of Guayaco for Treating Syphilis, a scene of a wealthy man receiving treatment for syphilis with the tropical wood guaiacum sometime around 1590.[121]

Tuskegee and Guatemala studies

The "Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male" was an infamous, unethical and racist

The Public Health Service started working on this study in 1932 in collaboration with

The 40-year study became a textbook example of criminally negligent

Similar experiments were carried out in

Names

Syphilis was first called grande verole or the "great pox" by the French. Other historical names have included "button scurvy", sibbens, frenga and dichuchwa, among others.[132][133] Since it was a disgraceful disease, the disease was known in several countries by the name of their neighbouring, often hostile country.[114] The English, the Germans, and the Italians called it "the French disease", while the French referred to it as the "Neapolitan disease". The Dutch called it the "Spanish/Castilian disease".[114] To the Turks it was known as the "Christian disease", whilst in India, the Hindus and Muslims named the disease after each other.[114]

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-55087-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Syphilis – CDC Fact Sheet (Detailed)". CDC. 2 November 2015. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ S2CID 23899851.

- ^ a b c d e f "Syphilis". CDC. 4 June 2015. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ PMID 27733282.

- ^ PMID 27733281.

- ^ PMID 19483520.

- ^ "Pinta". NORD. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ PMID 26646541.

- ^ from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ S2CID 947291.

- ^ PMID 19361976.

- ^ S2CID 24198278.

- ^ PMID 19237085.

- ISBN 978-0-323-75571-9.

- ^ "Syphilis". www.who.int. World Health Organization. 21 May 2024. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- PMID 10724044.

- ^ "Revisiting the Great Imitator, Part I: The Origin and History of Syphilis". www.asm.org. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-58110-207-9.

- ^ "STD Facts - Syphilis (Detailed)". www.cdc.gov. 23 September 2019. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ S2CID 211537893.

- ^ S2CID 19931104.

- ^ S2CID 207198662.

- PMID 17200385.

- ^ S2CID 2011299.

- PMID 15653827.

- ^ PMID 31253629.

- ^ "Ward 86 Practice Recommendations: Syphilis". hivinsite.ucsf.edu. Archived from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- PMID 29022569.

- ^ S2CID 242487360.

- ^ Cunningham F, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Spong CY, Dashe JS, Hoffman BL, Casey BM, Sheffield JS (2013). "Abortion". Williams Obstetrics. McGraw-Hill. p. 5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - PMID 26897633.

- PMID 24396138.

- ^ PMID 19805553.

- PMID 29022569.

- ^ a b "Transmission of Primary and Secondary Syphilis by Oral Sex --- Chicago, Illinois, 1998–2002". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. CDC. 21 October 2004. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ISBN 978-1-35118-825-8. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Syphilis & MSM (Men Who Have Sex With Men) - CDC Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 16 September 2010. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-7020-1258-7. Archivedfrom the original on 3 May 2016.

- PMID 22816000.

- PMID 18159528.

- ^ PMID 20797514.

- PMID 10194456.

- PMID 24135571.

- PMID 29528992.

- S2CID 25571961.

- ^ "Condom Fact Sheet in Brief | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 18 April 2019. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ a b "Syphilis - CDC Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 16 September 2010. Archived from the original on 16 September 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2007.

- ^ "A young man, J. Kay, afflicted with a rodent disease which has eaten away part of his face. Oil painting, ca. 1820". wellcomelibrary.org. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ PMID 15356931.

- PMID 19451577.

- ^ PMID 21683653.

- ^ "Prenatal Syphilis Screening Laws". www.cdc.gov. 8 April 2019. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- PMID 24958980.

- PMID 25352226.

- ^ "Trends in Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States: 2009 National Data for Gonorrhea, Chlamydia and Syphilis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 November 2010. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- PMID 27272583.

- ^ "National Notifiable Diseases". Public Health Agency of Canada. 5 April 2005. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- PMID 19415060.

- ^ "Table 6.5. Infectious Diseases Designated as Notifiable at the National Level-United States, 2009 [a]". Red Book. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-8589-1. Archivedfrom the original on 18 May 2016.

- PMID 17342669.

- (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ John Frith. "Syphilis – Its early history and Treatment until Penicillin and the Debate on its Origins". History. 20 (4).

- ^ "Sex and syphilis". Wellcome Collection. 30 April 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- S2CID 19322310.

- .

- ^ a b Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). "Syphilis-CDC fact sheet". CDC. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ "Syphilis guide: Treatment and follow-up". Government of Canada. 7 July 2022.

- PMID 22696367.

- PMID 30517548.

- ISBN 978-1-904455-10-3.

- PMID 9916946.

- PMID 11686978.

- ^ "Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization (WHO). 2004. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ "Syphilis". www.niaid.nih.gov. 27 October 2014. Archived from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ "STD Trends in the United States: 2010 National Data for Gonorrhea, Chlamydia, and Syphilis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 22 November 2010. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- PMID 25387188.

- from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ Paperny AM (31 March 2023). "Syphilis cases in babies skyrocket in Canada amid healthcare failures". reuters.

- ISBN 9780897330183.

- ^ S2CID 23899851.

- PMID 20596972.

- WHO. 30 June 2015. Archived from the originalon 4 September 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Summer 2007, pp. 55–56.

- PMID 15844068.

- ^ Baker, B. J. and Armelagos, G. J., (1988) "The origin and antiquity of syphilis: Paleopathological diagnosis and interpretation". Current Anthropology, 29, 703–738. https://doi.org/10.1086/203691. Powell, M. L. & Cook, D. C. (2005) The Myth of Syphilis: The natural history of treponematosis in North America. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. Williams, H. (1932) "The origin and antiquity of syphilis: The evidence from diseased bones, a review, with some new material from America". Archives of Pathology, 13: 779–814, 931–983.1932).

- ^ Dutour, O., et al. (Eds.). (1994). L'origine de la syphilis in Europe: avant ou après 1493? Paris, France: Éditions Errance. Baker, B. J. et al. (2020) "Advancing the Understanding of Treponemal Disease in the Past and Present". Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 171: 5–41. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.23988. Harper, K. N., Zuckerman, M. K., Harper, M. L., Kingston, J. D., Armelagos, G. J. (2011) "The origin and antiquity of syphilis revisited: An appraisal of Old World Pre-Columbian evidence of treponemal infections". Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 54: 99–133. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.21613.

- ^ For an introduction to this literature see Quétel, C. (1990). History of Syphilis. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Hemarjata P (17 June 2019). "Revisiting the Great Imitator: The Origin and History of Syphilis". American Society for Microbiology. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ Early work includes Henneberg, M., & Henneberg, R. J. (1994), "Treponematosis in an ancient Greek colony of Metaponto, southern Italy, 580-250 BCE" and Roberts, C. A. (1994), "Treponematosis in Gloucester, England: A theoretical and practical approach to the Pre-Columbian theory". Both in O. Dutour, et al. (Eds.), L'origine de la syphilis in Europe: avant ou après 1493? (pp. 92-98; 101–108). Paris, France: Éditions Errance.

- ^ Salmon M (13 July 2022). "Manuscripts and art support archaeological evidence that syphilis was in Europe long before explorers could have brought it home from the Americas". The Conversation. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- PMID 39694065.

- ^ Hudson, E. H. (1946). "A unitarian view of treponematosis". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 26 (1946), 135–139. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.1946.s1-26.135; "The treponematoses—or treponematosis?" The British Journal of Venereal Diseases, 34 (1958), 22–23; "Historical approach to the terminology of syphilis". Archives of Dermatology, 84 (1961), 545–562; "Treponematosis and man's social evolution". American Anthropologist, 67(4), 885–901. doi:10.1001/archderm.1961.01580160009002. On status see also Marylynn Salmon, Medieval Syphilis and Treponemal Disease (Leeds: Arc Humanities Press), 8, 30-33.

- ^ Grin, E. I. (1952) "Endemic Treponematosis in Bosnia: Clinical and epidemiological observations on a successful mass-treatment campaign". Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 7: 11-25.

- ^ Walker, D., Powers, N., Connell, B., & Redfern, R. (2015). "Evidence of skeletal treponematosis from the Medieval burial ground of St. Mary Spital, London, and implications for the origins of the disease in Europe". American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 156, 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22630 and Gaul, J.S., Grossschmidt, K., Budenbauer, C., & Kanz, Fabian (2015). "A probable case of congenital syphilis from pre-Columbian Austria". Anthropologischer Anzeiger, 72, 451–472. DOI: 10.1127/anthranz/2015/0504.

- ^ They include Henneberg, M., & Henneberg, R. J. (1994). "Treponematosis in an ancient Greek colony of Metaponto, southern Italy, 580-250 BCE". In O. Dutour, et al. (Eds.), L'origine de la syphilis in Europe: Avant ou après 1493? (pp. 92–98). Paris, France: Éditions Errance. Stirland, Ann. "Evidence for Pre-Columbian Treponematosis in Europe". In Dutour, O., Pálfi, G., Bérato, J., & Brun, J. -P. (Eds.). (1994). L'origine de la syphilis in Europe: avant ou après 1493? Paris, France: Éditions Errance, and Criminals and Paupers: The Graveyard of St. Margaret Fyebriggate in combusto, Norwich. With Contributions from Brian Ayers and Jayne Brown. East Anglian Archaeology 129. Dereham: Historic Environment, Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service, 2009. Erdal, Y. S. (2006). "A pre-Columbian case of congenital syphilis from Anatolia (Nicaea, 13th century AD)". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 16, 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.802. Cole G. and T. Waldron, "Apple Down 152: a putative case of syphilis from sixth century AD Anglo-Saxon England". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 2011 Jan;144(1):72-9. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21371. Epub 2010 Aug 18. PMID 20721939. Roberts, C. A. (1994). "Treponematosis in Gloucester, England: A theoretical and practical approach to the Pre-Columbian theory". In O. Dutour, et al. (Eds.), L'origine de la syphilis in Europe: avant ou après 1493? (pp. 101–108). Paris, France: Éditions Errance.

- ^ Baker, B.J. et al. (2020) "Advancing the Understanding of Treponemal Disease in the Past and Present". Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 171: 5–41. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.23988.

- ^ Fraser, C. M., Norris, S. J., Weinstock, G. M., White, O., Sutton, G. G., Dodson, R., ... Venter, J. C. (1998). "Complete genome sequence of Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete". Science, 281(5375), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001832. Čejková, D., Zobaníková, M., Chen, L., Pospíšilová, P., Strouhal, M., Qin, X., ... Šmajs, D. (2012). "Whole genome sequences of three Treponema pallidum ssp. pertenue strains: yaws and syphilis treponemes differ in less than 0.2% of the genome sequence". PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 6(1), e1471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015713. Mikalová, L., Strouhal, M., Čejková, D., Zobaníková, M., Pospíšilová, P., Norris, S. J., ... Šmajs, D. (2010). "Genome analysis of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum and subsp. pertenue strains: Most of the genetic differences are localized in six regions". PLoS ONE, 5, e15713. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0015713. Štaudová, B., Strouhal, M., Zobaníková, M., Čejková, D., Fulton, L. L., Chen, L., ... Šmajs, D. (2014). "Whole genome sequence of the Treponema pallidum subsp. endemicum strain Bosnia A: The genome is related to yaws treponemes but contains few loci similar to syphilis treponemes". PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 8(11), e3261. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003261.

- ^ Majander, K., Pfrengle S., Kocher, A., ..., Kühnert, J. K., Schuenemann, V. J. (2020), "Ancient Bacterial Genomes Reveal a High Diversity of Treponema pallidum Strains in Early Modern Europe". Current Biology 30, 3788–3803. Elsevier Inc. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.07.058.

- ^ See her Medieval Syphilis and Treponemal Disease (Leeds: Arc Humanities Press, 2022), 61-79.

- ^ Arrizabalaga, Jon. "The Changing Identity of the French Pox in Early Renaissance Castile". In Between Text and Patient: The Medical Enterprise in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, edited by Florence Eliza Glaze and Brian K. Nance, 397–417. Florence: SISMEL, 2011.

- ISBN 9781404209060. Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ Hidden Killers of the Tudor Home: The Horrors of Tudor Dentistry etc

- ISBN 978-0300113228.

- ISBN 9780674618763.

- ^ S2CID 6868863.

- PMID 15252975.

- ^ from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ Rayment M, Sullivan AK (April 2011). ""He who knows syphilis knows medicine"—the return of an old friend". Editorials. British Journal of Cardiology. 18: 56–58. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

"He who knows syphilis knows medicine" said Father of Modern Medicine, Sir William Osler, at the turn of the 20th Century. So common was syphilis in days gone by, all physicians were attuned to its myriad clinical presentations. Indeed, the 19th century saw the development of an entire medical subspecialty – syphilology – devoted to the study of the great imitator, Treponema pallidum.

- ISSN 1468-0289.

- Schaudinn FR, Hoffmann E (1905). "Vorläufiger Bericht über das Vorkommen von Spirochaeten in syphilitischen Krankheitsprodukten und bei Papillomen" [Preliminary report on the occurrence of Spirochaetes in syphilitic chancres and papillomas]. Arbeiten aus dem Kaiserlichen Gesundheitsamte. 22: 527–534.

- ^ "Salvarsan". Chemical & Engineering News. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ^ PMID 24653750.

- ISBN 978-0786724130. Archivedfrom the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ Halioua B (30 June 2003). "Comment la syphilis emporta Maupassant | La Revue du Praticien". www.larevuedupraticien.fr. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ Bernd M. "Nietzsche, Friedrich". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- S2CID 207268142.

- ISBN 978-0-307-38598-7.

- ISBN 978-1-85973-444-5.

- ISBN 978-0-8173-5534-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2 February 2016.

- ^ from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Tuskegee Study – Timeline". NCHHSTP. CDC. 25 June 2008. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- OCLC 496114416.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 15 January 2009. Archived(PDF) from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ^ "Final Report of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee". University of Virginia. May 1996. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ "Fact Sheet on the 1946-1948 U.S. Public Health Service Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Inoculation Study". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. n.d. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ "Guatemalans "died" in 1940s US syphilis study". BBC News. 29 August 2011. Archived from the original on 1 December 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- .

- National Public Radio. Archived from the originalon 10 November 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ Chris McGreal (1 October 2010). "US says sorry for "outrageous and abhorrent" Guatemalan syphilis tests". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

Conducted between 1946 and 1948, the experiments were led by John Cutler, a US health service physician who would later be part of the notorious Tuskegee syphilis study in Alabama in the 1960s.

- ISBN 9781444345926. Archivedfrom the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- S2CID 19185641.

Further reading

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA (February 2020). "The Modern Epidemic of Syphilis". N. Engl. J. Med. 382 (9): 845–854. S2CID 211537893.

- Ropper AH (October 2019). "Neurosyphilis". N. Engl. J. Med. 381 (14): 1358–1363. S2CID 242487360.

External links

- "Syphilis - CDC Fact Sheet" Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- UCSF HIV InSite Knowledge Base Chapter: Syphilis and HIV Archived 20 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Recommendations for Public Health Surveillance of Syphilis in the United States

- Pastuszczak M, Wojas-Pelc A (2013). "Current standards for diagnosis and treatment of syphilis: Selection of some practical issues, based on the European (IUSTI) and U.S. (CDC) guidelines". Advances in Dermatology and Allergology. 30 (4): 203–210. PMID 24278076.