Napoleon Sarony

Napoleon Sarony | |

|---|---|

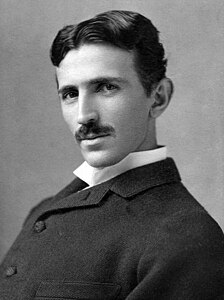

Self-portrait, late 19th century | |

| Born | March 9, 1821 |

| Died | November 9, 1896 (aged 75) New York City, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Photography |

Napoleon Sarony (March 9, 1821 – November 9, 1896)

Life

Sarony was born in 1821 in

Associations

Included among the thousands of people that came into Sarony's world were many distinguished people, such as American Civil War General

William T. Sherman

In 1888, Sarony photographed

Samuel Clemens; the Lotos, Salmagundi and Tile Clubs

Sarony took numerous photographs of

Oscar Wilde

One of Sarony's portraits of writer Oscar Wilde became the subject of a

Family

Sarony was married twice. His first wife, Ellen Major Sarony, died in 1858; his second wife, Louisa "Louie" Long Thomas Sarony (1838-1904), reportedly shared his tendency towards eccentricity and preference for outlandish dress.[1] She rented elaborate costumes that she wore during her daily afternoon walk through Washington Square, wearing them once before returning them.

His brother, Oliver François Xavier Sarony (1820–1879), was also a portrait photographer, working primarily in England, who died in 1879. Napoleon's son, Otto (1850–1903), continued the family name for a few years until his own death in 1903.

Sarony was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn.[3]

See also

Gallery

-

Joseph Jefferson as Rip Van Winkle, 1869

-

Actress Sarah Bernhardt

-

Sarah Bernhardt as Cleopatra, 1891

-

1850 print by Sarony and Major

-

Artist Thomas Moran, c. 1890–1896

-

photo of James Huneker c. 1890

-

"Sarony's Centennial Tableaux", showing young woman making U.S. Flag on sewing machine, c. 1876

-

Jasper Francis Cropsey, c. 1870

References

- ^ a b c Pauwels, Erin. "Napoleon Sarony's Living Pictures: The Celebrity Photograph in Gilded Age New York".

- ^ "Napoleon Sarony". National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Schmidt, Barbara. "Mark Twain, Napoleon Sarony and 'The damned old libel'". twainquotes.com. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ^ Scott US Stamp catalogue, identifier.[full citation needed]

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "London Bound American Writers in England (1870 - 1916)". University of Delaware, library. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- "Napoleon Sarony Dead". New York Times. November 10, 1896.