Nuzi

Yorghan Tepe | |

| |

| Location | Kirkuk Governorate, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 35°22′11.9″N 44°15′17.7″E / 35.369972°N 44.254917°E |

| Type | tell |

Nuzi (or Nuzu; Akkadian Gasur; modern Yorghan Tepe, Iraq) was an ancient Mesopotamian city southwest of the city of Arrapha (modern Kirkuk), located near the Tigris river. The site consists of one medium-sized multiperiod tell and two small single period mounds.[clarification needed]

History

The site showed occupation as far back as the late Uruk period. The city, then named Gasur, was founded in the third millennium during the time of the Akkadian Empire. One governor under the Akkadian Empire is known from a clay sealing reading "Itbe-labba, govern[or] of Gasur".[1] In the middle of the second millennium the Hurrians gained control of the town and renamed it Nuzi. The history of the site during the intervening period is unclear, though the presence of a few cuneiform tablets from Assyria indicates that trade with nearby Assur was taking place.

After the fall of the Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni Nuzi went into gradual decline. Note that while the Hurrian period is well known from full excavation of those strata, the earlier history is not as reliable because of less substantive digging.[2] The history of Nuzi is closely interrelated with that of the nearby towns of Eshnunna and Khafajah.

Archaeology

While tablets from Yorghan Tepe began appearing back as far as 1896, the first serious archaeological efforts began in 1925 after

[8][9][10][11] Excavations continued through 1931 with the site showing 15 occupation levels. The hundreds of tablets and other finds recovered were published in a series of volumes[12][13] with ongoing publications.[14]To date,

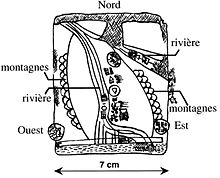

Perhaps the most famous item found is the Nuzi map, the oldest known map discovered. Although the majority of the tablet is preserved, it is unknown exactly what the Nuzi map shows. The Nuzi map is actually one of the so-called Gasur texts, and predates the invasion of the city of Gasur by the Hurrians, who renamed it Nuzi. The cache of economic and business documents among which the map was found date to the Old Akkadian period (ca. 2360–2180 BC).[17] Gasur was a thriving commercial center, and the texts reveal a diverse business community with far-reaching commercial activities. It is possible that Ebla was a trading partner, and that the tablet, rather than a record of land-holdings, might indeed be a road map.[17] The tablet, which is approximately 6 × 6.5 cm., is inscribed only on the obverse. It shows the city of Maskan-dur-ebla in the lower left corner, as well as a canal/river and two mountain ranges.[17]

Nuzi ware

In 1948, archaeologist Max Mallowan called attention to the unusual pottery he found at Nuzi, associated with the Mitanni period. This became known as the Nuzi ware. Subsequently, this highly artistic pottery was identified all over in the Upper Mesopotamia.[18]

Nuzi, a provincial town in the 14th century BC

The best-known period in the history of Yorghan Tepe is by far one of the city of Nuzi in the 15th-14th centuries BC. The tablets of this period indicate that Nuzi was a small provincial town of northern Mesopotamia at this time in an area populated mostly by Assyrians and Hurrians, the latter a people well known though poorly documented, and that would be even less if not for the information uncovered at this site.

Administration

Nuzi was a provincial town of Arrapha. It was administered by a governor (šaknu) from the palace. The palace, situated in the center of the mound, had many rooms arranged around a central courtyard. The functions of some of those rooms have been identified: reception areas, apartments, offices, kitchens, stores. The walls were painted, as was seen in fragments unearthed in the ruins of the building.

Archives that have been exhumed tell us about the royal family, as well as the organization of the internal administration of the palace and its dependencies, and the payments various workers received. Junior officers of the royal administration had such titles as sukkallu (often translated as "vizier", the second governor), "district manager" (halṣuhlu), and "mayor" (hazannu). Justice was rendered by these officers, but also by judges (dayānu) installed in the districts.

Free subjects of the state were liable to a conscription, the Ilku, which consisted of a requirement to perform various types of military and civilian services, such as working the land.

See also

Notes

- ^ Lewy, Julius, "Notes on Pre-Ḫurrian Texts from Nuzi", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 58, no. 3, pp. 450–61, 1938

- OCLC 614578502.

- S2CID 163178475.

- ^ [1] Richard F. S. Starr, Nuzi: report on the excavation at Yorgan Tepa near Kirkuk, Iraq, conducted by Harvard university in conjunction with the American Schools of Oriental Research and the University museum of Philadelphia, 1927-1931. v. 1: text, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1939

- ^ Richard F. S. Starr, Nuzi: Report on the Excavation at Yorgan Tepa near Kirkuk, Iraq, Conducted by Harvard University in Conjunction with the American Schools of Oriental Research and the University museum of Philadelphia 1927-1931, Volume 2: Plates and Plans, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1937

- ^ [2] Edward Chiera. Excavations at Nuzi: Vol. I. Texts of varied content, selected and copied, Harvard University Press, 1929

- ^ [3] Robert H. Pfeiffer, Excavations at Nuzi: Volume II, The Archives of Shilwateshub Son of the King, Harvard University Press, 1932

- ^ [4] T.J. Meek, Excavations at Nuzi III: Old Akkadian, Sumerian, and Cappadocian Texts from Nuzi, Harvard University Press, 1935

- ^ [5] Robert H. Pfeiffer and Ernest R. Lacheman, Excavations at Nuzi: Volume IV Miscellaneous Texts From Nuzi Part I, Harvard University Press, 1942

- ^ E.R. Lacheman, Excavations at Nuzi V: Miscellaneous Texts from Nuzi, Part 2: The Palace and Temple Archives, Harvard University Press, 1950

- ^ E.R. Lacheman, Excavations at Nuzi VI: The Administrative Archives, Harvard University Press, 1955

- ^ [6] E.R. Lacheman, Excavations at Nuzi VII: Economic and Social Documents, Harvard University Press, 1958

- ^ [7] Ernest R. Lacheman, Excavations at Nuzi Volume VIII: Family Law Documents, Harvard University Press, 1962

- OCLC 51898595.

- S2CID 163837436.

- ISSN 0081-9271.

- ^ S2CID 186746259.

- ^ Abdullah Bakr Othman (2018), The Distribution of the Nuzi ware in Northern Iraq and Syria. Polytechnic Journal: Vol.8 No. 2 (May 2018): Pp: 347-371

Further reading

- Martha A. Morrison and David I. Owen, Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians: Volume 1 – In Honor of Ernest R. Lacheman on His Seventy-fifth Birthday, April 29, 1981, 1981, ISBN 978-0-931464-08-9

- David I. Owen and Martha A. Morrison, Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians: Volume 2 – General Studies and Excavations at Nuzi 9/1, 1987, ISBN 978-0-931464-37-9

- Ernest R. Lacheman and Maynard P. Maidman, Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians: Volume 3 – Joint Expedition with the Iraq Museum at Nuzi VII – Miscellaneous Texts, 1989, ISBN 978-0-931464-45-4

- Ernest R. Lacheman et al., Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians: Volume 4 – The Eastern Archives of Nuzi and Excavations at Nuzi 9/2, Eisenbrauns, 1993, ISBN 0-931464-64-1

- David I. Owen and Ernest R. Lacheman, Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians: Volume 5 – General Studies and Excavations at Nuzi 9/3, Eisenbrauns, 1995, ISBN 0-931464-67-6

- Maynard P. Maidman, Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians: Volume 6 – Two Hundred Nuzi Texts from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, CDL Press, 1994, ISBN 978-1-883053-05-5

- David I. Owen and Gernot Wilhelm, Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians: Volume 7 – Edith Porada Memorial Volume, CDL Press, 1995, ISBN 1-883053-07-2

- David I. Owen and Gernot Wilhelm, Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians: Volume 8 – Richard F.S. Starr Memorial Volume, CDL Press, 1997, ISBN 1-883053-10-2

- David I. Owen and Gernot Wilhelm, Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians: Volume 9 – General Studies and Excavations at Nuzi, CDL Press, 1998, ISBN 1-883053-26-9

- David I. Owen and Gernot Wilhelm, Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians: Volume 10 – Nuzi at seventy-five, Bethesda, Md. : CDL Press, 1999, ISBN 9781883053505

- Brigitte Lion and Diana L. Stein, Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians: Volume 11 – The Pula-Hali Family Archives, CDL Press, 2001, ISBN 1-883053-56-0

- G. R. Driverand J. Miles, Ordeal by Oath at Nuzi, Iraq, vol. 7, pp. 132, 1940

- J. Paradise, "A Daughter and Her Father's Property at Nuzi", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 32, pp. 189–207, 1980

- [8] Ignace J. Gelb et al., "Nuzi Personal Names", Oriental Institute Publications 57, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1943