Assur

Aššur ܐܫܘܪ آشور | |

American soldiers on guard at the ruins of Ashur, 2008 | |

| Location | Saladin Governorate, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 35°27′24″N 43°15′45″E / 35.45667°N 43.26250°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | Early Dynastic Period |

| Abandoned | 3rd century AD[1] |

| Periods | Early Bronze Age to classical antiquity |

| Site notes | |

| Public access | Inaccessible (in a war zone) [citation needed] [needs update] |

Arab States | |

| Endangered | 2003–present |

Aššur (

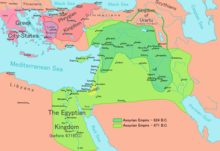

Occupation of the city itself continued for approximately 3,000 years,[4] from the Early Dynastic Period to the mid-3rd century AD, when the city was sacked by the Sasanian Empire. The site is a World Heritage Site and was added to that organisation's list of sites in danger in 2003 as a result of a proposed dam, which would flood some of the site. It has been further threatened by the conflict that erupted following the US-led 2003 invasion of Iraq. Assur lies 65 kilometres (40 mi) south of the site of Nimrud and 100 km (60 mi) south of Nineveh.

History of research

Exploration of the site of Assur began in 1898 by German archaeologists. Excavations began in 1900 by Friedrich Delitzsch, and were continued in 1903–1913 by a team from the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft led initially by Robert Koldewey and later by Walter Andrae.[5][6][7][8][9] More than 16,000 clay tablets with cuneiform texts were discovered. The German archeologists brought objects they found to Berlin enhancing the collection of the Pergamon Museum.

More recently, Ashur was excavated by B. Hrouda for the

Name

Aššur is the name of the city, of the land ruled by the city, and of its

History

Early Bronze Age

According to the Oxford Companion to the Bible, Assur was "built on a

Old and Middle Assyrian Periods

By the time the Neo-Sumerian Ur-III dynasty collapsed at the hands of the

In around 2000 BC,

Not long after, the native king Adasi expelled the Babylonians and Amorites from Assur and Assyria as a whole around 1720 BC, although little is known of his successors. Evidence of further building activity is known from a few centuries later, during the reign of a native king Puzur-Ashur III, when the city was refortified and the southern districts incorporated into the main city defenses. Temples to the moon god Sin (Nanna) and the sun god Shamash were built and dedicated through the 15th century BC. The city was subsequently subjugated by the king of Mitanni, Shaushtatar in the late 15th century, taking the gold and silver doors of the temple to his capital, Washukanni, as spoils.[13]

Neo-Assyrian Empire

In the

With the reign of Sargon II (722–705 BC), a new capital began to rise: Dur-Sharrukin (Fortress of Sargon). Dur-Sharrukin was originally planned to be built on a scale set to surpass that of Ashurnasirpal's.[15] He died in battle and his son and successor Sennacherib (705–682 BC) abandoned the city, choosing to magnify Nineveh as his royal capital. The city of Ashur remained the religious center of the empire and continued to be revered as the holy crown of the empire, due to its temple of the national god Ashur.[16]

In the reign of Sennacherib (705–682 BC), the House of the New Year, Akitu, was built, and the festivities celebrated in the city. Many of the kings were also buried beneath the Old Palace while some queens were buried in the other capitals such as the wife of Sargon, Ataliya. The city was sacked and largely destroyed during the decisive battle of Assur, a major confrontation between the Assyrian and Median armies.[17][18]

Achaemenid Empire

After the Medes were overthrown by the

Parthian Empire

The city revived during the

Assyrian

German semiticist Klaus Beyer (1929-2014) published over 600 inscriptions from Mesopotamian towns and cities including Ashur, Dura-Europos, Hatra, Gaddala, Tikrit and Tur Abdin. Given that Christianity had begun to spread amongst the Assyrians throughout the Parthian era, the original Assyrian culture and religion persisted for some time, as proven by the inscriptions that include invocations to the gods Ashur, Nergal, Nanna, Ishtar, Tammuz and Shamash, as well as mentions of citizens having compound names that refer to Assyrian gods, such as ʾAssur-ḥēl (Ashur [is] my strength), ʾAssur-emar (Ashur decreed/commanded), ʾAssur-ntan (Ashur gave [a son]), and ʾAssur-šma' (Ashur has heard; cf. Esarhaddon).[20]

The Roman historian Festus wrote in about 370 that in AD 116 Trajan formed from his conquests east of the Euphrates the new Roman provinces of Mesopotamia and Assyria. The existence of the latter Roman province is questioned by C.S. Lightfoot and F. Miller.[21][22] In any case, just two years after the province's supposed creation, Trajan's successor Hadrian restored Trajan's eastern conquests to the Parthians, preferring to live with him in peace and friendship.[23]

There were later Roman incursions into Mesopotamia under Lucius Verus and under Septimius Severus, who set up the Roman provinces of Mesopotamia and the Neo-Assyrian kingdom of Osroene.

Assur was captured and sacked by Ardashir I of the Sasanian Empire c. 240 AD, whereafter the city was largely destroyed and much of its population was dispersed.[1]

Threats to Assur

The site was put on UNESCO's List of World Heritage in Danger in 2003, at which time the site was threatened by a looming large-scale dam project that would have submerged the ancient archaeological site.[24][25] The dam project was put on hold shortly after the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

The territory around the ancient site was occupied by the

As of February 2017, the group no longer controls the site; however, it is not secure enough for archaeological experts to evaluate.[28]

See also

- Ashurism

- Chronology of the ancient Near East

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- Kings of Assyria

- Short chronology timeline

- Assyrian homeland

Notes

- ^ a b Radner 2015, pp. 7, 19.

- ^ Also phonetically 𒀀𒇳𒊬 a-šur4 or 𒀸𒋩 aš-šur Sumerian dictionary entry Aššur (GN)

- ISBN 978-1-61451-426-8.

- ^ Radner 2015, p. 2.

- ISBN 3-7648-1805-0)

- ISBN 3-535-00587-6)

- ISBN 3-7648-1806-9)

- ^ Walter Andrae, Hethitische Inschriften auf Bleistreifen aus Assur, JC Hinrichs, 1924

- ISBN 3-406-02947-7)

- ^ Excavations in Iraq 1989–1990, Iraq, vol. 53, pp. 169-182, 1991

- ^ R. Dittmann, Ausgrabungen der Freien Universitat Berlin in Ashur und Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta in den Jahren 1986-1989, MDOG, vol. 122, pp. 157–171, 1990

- ^ Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. (1993). "Assyria". The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b c d e f Mark, Joshua J. (2014-06-30). "Ashur". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. (2014-08-03). "Kalhu / Nimrud". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. (2014-07-05). "Dur-Sharrukin". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East "In 614 BC Assur was conquered by the Medes under king Cyaxares (625-585 BC)"

- ^ A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East "In 614 BC Assur was conquered by the Medes under king Cyaxares (625-585 BC)"

- ^ The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem: Judah Under Babylonian Rule "the Medes left Arrapha, attacked Kalhu (Nimrud) and Ninuwa (Nineveh), and continued rapidly northward to capture the nearby city of Tarbisu. Afterward, they went back down the Tigris and laid siege to the city of Assur. The Babylonian army came to the aid of the Medes only after the Medes had begun the decisive offensive against the city, capturing it, killing many of its residents, and taking many others captive."

- ^ "Assyrians after Assyria". Nineveh.com. 4 September 1999. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ Beyer 1998, p. 155

- ^ C. S. Lightfoot, "Trajan's Parthian War and the Fourth-Century Perspective" in The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 80 (1990), pp. 115-126

- ^ Simon Grote, "Another look at the Breviarium of Festus" in The Classical Quarterly, Volume 61, Issue 2 (December 2011), pp. 704-721

- ^ Theodore Mommsen, Römische Geschichte (Berlin 1885), vol. V (Die Provinzen von Caesar bis Diocletian), p. 403

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage in Danger 2003

- ^ At the Iraqi Site of Assur, Ancient History Stands at Risk of Destruction - Smithsonian Magazine - January 2022

- ^ Mezzofiore, Gianluca; Limam, Arij (28 May 2015). "Iraq: Isis 'blows up Unesco world heritage Assyrian site of Ashur' near Tikrit". International Business Times. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ "Iraq Assur | AP Archive". www.aparchive.com. 2016-12-11. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- ^ "Iraqis seek funds to restore cultural artifacts recovered from ISIS". CBS News. Associated Press. February 24, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

References

- Beyer, Klaus (1998). Die aramäischen Inschriften aus Assur, Hatra und dem übrigen Ostmesopotamien. Germany.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Walter Andrae: Babylon. Die versunkene Weltstadt und ihr Ausgräber Robert Koldewey. de Gruyter, Berlin 1952.

- Stefan Heidemann: Al-'Aqr, das islamische Assur. Ein Beitrag zur historischen Topographie Nordmesopotamiens. In: Karin Bartl and Stefan hauser et al. (eds.): Berliner Beiträge zum Vorderen Orient. Seminar fur Altorientalische Philologie und Seminar für Vorderasiatische Altertumskunde der Freien Universität Berlin, Fachbereich Altertumswissenschaften. Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin 1996, pp. 259–285

- Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum: Die Assyrer. Geschichte, Gesellschaft, Kultur. C.H.Beck Wissen, München 2003. ISBN 3-406-50828-6

- Olaf Matthes: Zur Vorgeschichte der Ausgrabungen in Assur 1898-1903/05. MDOG Berlin 129, 1997, 9-27. ISSN 0342-118X

- Peter A. Miglus: Das Wohngebiet von Assur, Stratigraphie und Architektur. Berlin 1996. ISBN 3-7861-1731-4

- Susan L. Marchand: Down from Olympus. Archaeology and Philhellenism in Germany 1750–1970. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1996. ISBN 0-691-04393-0

- Conrad Preusser: Die Paläste in Assur. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1955, 1996. ISBN 3-7861-2004-8

- Friedhelm Pedde, The Assur-Project. An old excavation newly analyzed, in: J.M. Córdoba et al. (Ed.), Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Madrid, April 3–8, 2006. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Ediciones, Madrid 2008, Vol. II, 743–752.https://www.jstor.org/stable/41147573

- Steven Lundström, From six to seven Royal Tombs. The documentation of the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft excavation at Assur (1903-1914) – Possibilities and limits of its reexamination, in: J.M. Córdoba et al. (Ed.), Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Madrid, April 3–8, 2006. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Ediciones, Madrid 2008, Vol. II, 445–463.

- Friedhelm Pedde, The Assur-Project: A new Analysis of the Middle- and Neo-Assyrian Graves and Tombs, in: P. Matthiae – F. Pinnock – L. Nigro – N. Marchetti (Ed.), Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, May, 5th-10th 2008, "Sapienza" – Università di Roma. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2010, Vol. 1, 913–923.

- Barbara Feller, Seal Images and Social Status: Sealings on Middle Assyrian Tablets from Ashur, in: P. Matthiae – F. Pinnock – L. Nigro – N. Marchetti (Ed.), Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, May, 5th-10th 2008, "Sapienza" – Università di Roma. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2010, Vol. 1, 721–729.

- Friedhelm Pedde, The Assur Project: The Middle and Neo-Assyrian Graves and Tombs, in: R. Matthews – J. Curtis (Ed.), Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, London 2010. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2012, Vol. 1, 93–108.

- Friedhelm Pedde, The Assyrian heartland, in: D.T. Potts (Ed.), A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester 2012, Vol. II, 851–866.

- Radner, Karen (2015). Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction. New York: OCLC 1202732830.

External links

- Schippmann, K. (1987). "ASSYRIA iii. Parthian Assur". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 8. pp. 816–817.

- Assyrian origins: discoveries at Ashur on the Tigris: antiquities in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Assur

- Friedhelm Pedde, Recovering Assur. From the German Excavations of 1903–1914 to today's Assur Project in Berlin [1]