Pseudoknot

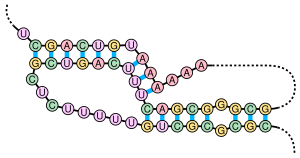

A pseudoknot is a nucleic acid secondary structure containing at least two stem-loop structures in which half of one stem is intercalated between the two halves of another stem. The pseudoknot was first recognized in the turnip yellow mosaic virus in 1982.[2] Pseudoknots fold into knot-shaped three-dimensional conformations but are not true topological knots. These structures are categorized as cross (X) topology within the circuit topology framework, which, in contrast to knot theory, is a contact-based approach.

Prediction and identification

The structural configuration of pseudoknots does not lend itself well to bio-computational detection due to its context-sensitivity or "overlapping" nature. The

It is possible to identify a limited class of pseudoknots using dynamic programming, but these methods are not exhaustive and scale worse as a function of sequence length than non-pseudoknotted algorithms.

Biological significance

Several important biological processes rely on RNA molecules that form pseudoknots, which are often RNAs with extensive

Representing pseudoknots

Many types of pseudoknots exist, differing by how they cross and how many times they cross. To reflect this difference, pseudoknots are classed into H-, K-, L-, M-types, with each successive type adding a layer of step intercalation. The simple telomerase P2b-P3 example in the article, for example, is an H-type pseudoknot.[8]

RNA secondary structure is usually represented by the dot-bracket notation, with pairing round brackets () indicating basepairs in a stem and dots representing loops. The interrupted stems of pseudoknots mean that such notation must be extended with extra brackets, or even letters, so that different sets of stems can be represented. One such extension uses, in nesting order, ([{<ABCDE for opening and edcba>}]) for closing.[9] The structure for the two (slightly varying) telomerase examples, in this notation, is:

(((.(((((........))))).))). ....]]]]]]. drawing 1 CGCGCGCUGUUUUUCUCGCUGACUUUCAGCGGGCGA---AAAAAAUGUCAGCU 50 ALIGN |.||||||||||||||||||||||||| .|.| |||||| ||||||. 1ymo 1 ---GGGCUGUUUUUCUCGCUGACUUUCAGC--CCCAAACAAAAAA-GUCAGCA 47 ((((((........)))) )).........]]]]]].

Note that U bulge at the end is normally present in telomerase RNA. It was removed in the 1ymo solution model for enhanced stability of the pseudoknot.[10]

See also

References

- ^ PMID 15849264.

- PMID 15941360.

- ^ Rivas E, Eddy S. (1999). "A dynamic programming algorithm for RNA structure prediction including pseudoknots". J Mol Biol 285(5): 2053–2068.

- ^ Dirks, R.M. Pierce N.A. (2004) An algorithm for computing nucleic acid base-pairing probabilities including pseudoknots. "J Computation Chemistry". 25:1295-1304, 2004.

- ^ Lyngsø RB, Pedersen CN. (2000). "RNA pseudoknot prediction in energy-based models". J Comput Biol 7(3–4): 409–427.

- ^ Lyngsø, R. B. (2004). Complexity of pseudoknot prediction in simple models. Paper presented at the ICALP.

- PMID 4000943.

- PMID 26428288.

- PMID 29236971.

- PMID 15749017.

External links