Nucleic acid tertiary structure

Nucleic acid tertiary structure is the three-dimensional shape of a nucleic acid polymer.[1] RNA and DNA molecules are capable of diverse functions ranging from molecular recognition to catalysis. Such functions require a precise three-dimensional structure. While such structures are diverse and seemingly complex, they are composed of recurring, easily recognizable tertiary structural motifs that serve as molecular building blocks. Some of the most common motifs for RNA and DNA tertiary structure are described below, but this information is based on a limited number of solved structures. Many more tertiary structural motifs will be revealed as new RNA and DNA molecules are structurally characterized.

Helical structures

Double helix

The double helix is the dominant tertiary structure for biological DNA, and is also a possible structure for RNA. Three DNA conformations are believed to be found in nature,

The double helix makes one complete turn about its axis every 10.4–10.5 base pairs in solution. This frequency of twist (known as the helical pitch) depends largely on stacking forces that each base exerts on its neighbours in the chain. Double-helical RNA adopts a conformation similar to the A-form structure.Other conformations are possible; in fact, only the letters F, Q, U, V, and Y are now available to describe any new DNA structure that may appear in the future.[4][5] However, most of these forms have been created synthetically and have not been observed in naturally occurring biological systems.

Major and minor groove triplexes

The minor groove triplex is a ubiquitous RNA structural motif. Because interactions with the minor groove are often mediated by the 2'-OH of the ribose sugar, this RNA motif looks very different from its DNA equivalent. The most common example of a minor groove triple is the A-minor motif, or the insertion of adenosine bases into the minor groove (see above). However, this motif is not restricted to adenosines, as other nucleobases have also been observed to interact with the RNA minor groove.

The minor groove presents a near-perfect complement for an inserted base. This allows for optimal van der Waals contacts, extensive hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic surface burial, and creates a highly energetically favorable interaction.[8][9] Because minor groove triples are capable of stably packing a free loop and helix, they are key elements in the structure of large ribonucleotides, including the group I intron,[10] the group II intron,[11] and the ribosome.

Although the major groove of standard A-form RNA is fairly narrow and therefore less available for triplex interaction than the minor groove, major groove triplex interactions can be observed in several RNA structures. These structures consist of several combinations of

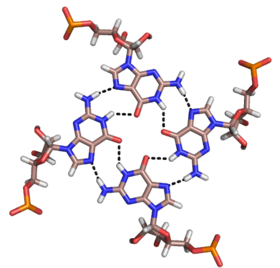

Quadruplexes

Besides

The core of malachite green aptamer is also a kind of base quadruplex with a different hydrogen bonding pattern (See Figure).[13] The quadruplex can repeat several times consecutively, producing an immensely stable structure.

The unique structure of quadruplex regions in RNA may serve different functions in a biological system. Two important functions are the binding potential with

Along with these functions, the G-quadruplex in the mRNA around the ribosome binding regions could serve as a regulator of gene expression in bacteria.[19] There may be more interesting structures and functions yet to be discovered in vivo.

Coaxial stacking

Coaxial stacking, otherwise known as helical stacking, is a major determinant of higher order RNA tertiary structure. Coaxial stacking occurs when two RNA duplexes form a contiguous helix, which is stabilized by

In 1994, Walter and Turner determined the free energy contributions of nearest neighbor stacking interactions within a helix-helix interface by using a model system that created a helix-helix interface between a short oligomer and a four-nucleotide overhang at the end of a hairpin stem . Their experiments confirmed that the thermodynamic contribution of base-stacking between two helical secondary structures closely mimics the thermodynamics of standard duplex formation (nearest neighbor interactions predict the thermodynamic stability of the resulting helix). The relative stability of nearest neighbor interactions can be used to predict favorable coaxial stacking based on known secondary structure. Walter and Turner found that, on average, prediction of RNA structure improved from 67% to 74% accuracy when coaxial stacking contributions were included.[23]

Most well-studied RNA tertiary structures contain examples of coaxial stacking. Some prominent examples are tRNA-Phe, group I introns, group II introns, and ribosomal RNAs. Crystal structures of tRNA revealed the presence of two extended helices that result from coaxial stacking of the amino-acid acceptor stem with the T-arm, and stacking of the D- and anticodon-arms. These interactions within

Two common motifs involving coaxial stacking are kissing loops and pseudoknots. In kissing loop interactions, the single-stranded loop regions of two hairpins interact through base pairing, forming a composite, coaxially stacked helix. Notably, this structure allows all of the nucleotides in each loop to participate in base-pairing and stacking interactions. This motif was visualized and studied using NMR analysis by Lee and Crothers.[27] The pseudoknot motif occurs when a single stranded region of a hairpin loop base-pairs with an upstream or downstream sequence within the same RNA strand. The two resulting duplex regions often stack upon one another, forming a stable coaxially stacked composite helix. One example of a pseudoknot motif is the highly stable Hepatitis Delta virus ribozyme, in which the backbone shows an overall double pseudoknot topology.[28]

An effect similar to coaxial stacking has been observed in rationally designed DNA structures. DNA origami structures contain a large number of double helixes with exposed blunt ends. These structures were observed to stick together along the edges that contained these exposed blunt ends, due to the hydrophobic stacking interactions.[29] By combining these rationally designed DNA nanostructures and DNA-PAINT super-resolution imaging, researchers discerned individual strength of stacking energies between all possible dinucleotides.[30]

Measurement of coaxial stacking in nucleic acid

Early measurements of coaxial stacking were performed using biochemical assays that studies the relative migration of different nucleic acid molecules based on their conformation and the kind of interactions present. Short DNA molecules containing nicks that could still stack coaxially migrated faster than DNA molecules containing gaps and thus had no coaxial stacking. This could be explained by polymeric properties of DNA where are more rigid rod like molecule will migrate faster along an electrical gradient in a matrix compared to a more flexible molecule.[31] Development of newer techniques such as optical tweezers and the ability to fold DNA nanostructures led to measurement so of DNA bundles and their ability to stack with each other. The force needed to pull these bundles apart using optical tweezers could then be analyzed to measure the base-pair stacking energies.[32] These measurements were performed mainly under non-equilibrium conditions and various extrapolations were made to arrive at the exact values of coaxial stacking between bases. Recent single-molecule studies using DNA nanostructures and DNA-PAINT super-resolution microscopy has allowed for measurement of these interaction between dinucleotides using in-depth kinetic analysis of binding times of short DNA molecules to their complimentary sequences in the presence or absence of DNA-stacking interactions.[30]

Other motifs

Tetraloop-receptor interactions

Tetraloop-receptor interactions combine base-pairing and stacking interactions between the loop nucleotides of a tetraloop motif and a receptor motif located within an RNA duplex, creating a tertiary contact that stabilizes the global tertiary fold of an RNA molecule. Tetraloops are also possible structures in DNA duplexes.[34]

Stem-loops can vary greatly in size and sequence, but tetraloops of four

“Tetraloop receptor motifs” are long-range tertiary interactions

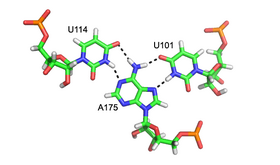

For example, the self-splicing group I intron relies on tetraloop receptor motifs for its structure and function.[25][40] Specifically, the three adenine residues of the canonical GAAA motif stack on top of the receptor helix and form multiple stabilizing hydrogen bonds with the receptor. The first adenine of the GAAA sequence forms a triple base-pair with the receptor AU bases. The second adenine is stabilized by hydrogen bonds with the same uridine, as well as via its 2'-OH with the receptor and via interactions with the guanine of the GAAA tetraloop. The third adenine forms a triple base pair.

A-minor motif

The A-minor motif is a ubiquitous RNA

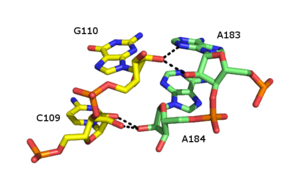

A-minor motifs have been separated into four classes,[8][9] types 0 to III, based upon the position of the inserting base relative to the two 2’-OH's of the Watson-Crick base pair. In type I and II A-minor motifs, N3 of adenine is inserted deeply within the minor groove of the duplex (see figure: A minor interactions - type II interaction), and there is good shape complementarity with the base pair. Unlike types 0 and III, type I and II interactions are specific for adenine due to hydrogen bonding interactions. In the type III interaction, both the O2' and N3 of the inserting base are associated less closely with the minor groove of the duplex. Type 0 and III motifs are weaker and non-specific because they are mediated by interactions with a single 2’-OH (see figure: A-minor Interactions - type 0 and type III interactions).

The A-minor motif is among the most common RNA structural motifs in the ribosome, where it contributes to the binding of tRNA to the 23S subunit.[43] They most often stabilize RNA duplex interactions in loops and helices, such as in the core of group II introns.[6]

An interesting example of A-minor is its role in

An analysis of A-minor motifs in the 23S ribosomal RNA has revealed a hierarchical network of structural dependencies, suggested to be related to ribosomal evolution and to the order of events that led to the development of the modern bacterial large subunit.[45]

The A-minor motif and it's novel subclass, WC/H A-minor interactions, are reported to fortify other RNA tertiary structures such as major groove triple helices identified in RNA stabilization elements.[16][15]

Ribose zipper

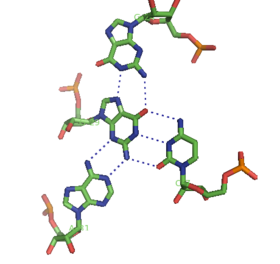

The ribose zipper is an

Numerous forms of ribose zipper have been reported, but a common type involves four hydrogen bonds between 2'-OH groups of two adjacent sugars. Ribose zippers commonly occur in arrays that stabilize interactions between separate RNA strands. on the second chain.

Role of metal ions

Functional RNAs are often folded, stable molecules with three-dimensional shapes rather than floppy, linear strands.[50] Cations are essential for thermodynamic stabilization of RNA tertiary structures. Metal cations that bind RNA can be monovalent, divalent or trivalent. Potassium (K+) is a common monovalent ion that binds RNA. A common divalent ion that binds RNA is magnesium (Mg2+). Other ions including sodium (Na+), calcium (Ca2+) and manganese (Mn2+) have been found to bind RNA in vivo and in vitro. Multivalent organic cations such as spermidine or spermine are also found in cells and these make important contributions to RNA folding. Trivalent ions such as cobalt hexamine or lanthanide ions such as terbium (Tb3+) are useful experimental tools for studying metal binding to RNA.[51][52]

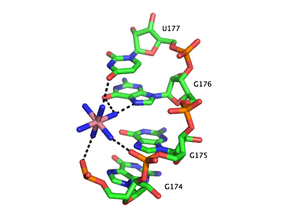

A metal ion can interact with RNA in multiple ways. An ion can associate diffusely with the RNA backbone, shielding otherwise unfavorable

Metal-binding sites are often localized in the deep and narrow major groove of the RNA duplex, coordinating to the Hoogsteen edges of purines. In particular, metal cations stabilize sites of backbone twisting where tight packing of phosphates results in a region of dense negative charge. There are several metal ion-binding motifs in RNA duplexes that have been identified in crystal structures. For instance, in the P4-P6 domain of the Tetrahymena thermophila group I intron, several ion-binding sites consist of tandem G-U wobble pairs and tandem G-A mismatches, in which divalent cations interact with the Hoogsteen edge of guanosine via O6 and N7.[53][54][55] Another ion-binding motif in the Tetrahymena group I intron is the A-A platform motif, in which consecutive adenosines in the same strand of RNA form a non-canonical pseudobase pair.[56] Unlike the tandem G-U motif, the A-A platform motif binds preferentially to monovalent cations. In many of these motifs, absence of the monovalent or divalent cations results in either greater flexibility or loss of tertiary structure.

Divalent metal ions, especially magnesium, have been found to be important for the structure of DNA junctions such as the Holliday junction intermediate in genetic recombination. The magnesium ion shields the negatively charged phosphate groups in the junction and allows them to be positioned closer together, allowing a stacked conformation rather than an unstacked conformation.[57] Magnesium is vital in stabilizing these kinds of junctions in artificially designed structures used in DNA nanotechnology, such as the double crossover motif.[58]

History

The earliest work in RNA structural biology coincided, more or less, with the work being done on DNA in the early 1950s. In their seminal 1953 paper, Watson and Crick suggested that van der Waals crowding by the 2`OH group of ribose would preclude RNA from adopting a double helical structure identical to the model they proposed - what we now know as B-form DNA.[59] This provoked questions about the three dimensional structure of RNA: could this molecule form some type of helical structure, and if so, how?

In the mid-1960s, the role of tRNA in protein synthesis was being intensively studied. In 1965, Holley et al. purified and sequenced the first tRNA molecule, initially proposing that it adopted a cloverleaf structure, based largely on the ability of certain regions of the molecule to form stem loop structures.[60] The isolation of tRNA proved to be the first major windfall in RNA structural biology. In 1971, Kim et al. achieved another breakthrough, producing crystals of yeast tRNAPHE that diffracted to 2-3 Ångström resolutions by using spermine, a naturally occurring polyamine, which bound to and stabilized the tRNA.[61]

For a considerable time following the first tRNA structures, the field of RNA structure did not dramatically advance. The ability to study an RNA structure depended upon the potential to isolate the RNA target. This proved limiting to the field for many years, in part because other known targets - i.e., the ribosome - were significantly more difficult to isolate and crystallize. As such, for some twenty years following the original publication of the tRNAPHE structure, the structures of only a handful of other RNA targets were solved, with almost all of these belonging to the transfer RNA family.[62]

This unfortunate lack of scope would eventually be overcome largely because of two major advancements in nucleic acid research: the identification of ribozymes, and the ability to produce them via in vitro transcription. Subsequent to Tom Cech's publication implicating the Tetrahymena group I intron as an autocatalytic ribozyme,[63] and Sidney Altman's report of catalysis by ribonuclease P RNA,[64] several other catalytic RNAs were identified in the late 1980s,[65] including the hammerhead ribozyme. In 1994, McKay et al. published the structure of a 'hammerhead RNA-DNA ribozyme-inhibitor complex' at 2.6 Ångström resolution, in which the autocatalytic activity of the ribozyme was disrupted via binding to a DNA substrate.[66] In addition to the advances being made in global structure determination via crystallography, the early 1990s also saw the implementation of NMR as a powerful technique in RNA structural biology. Investigations such as this enabled a more precise characterization of the base pairing and base stacking interactions which stabilized the global folds of large RNA molecules.

The resurgence of RNA structural biology in the mid-1990s has caused a veritable explosion in the field of nucleic acid structural research. Since the publication of the hammerhead and P4-6 structures, numerous major contributions to the field have been made. Some of the most noteworthy examples include the structures of the

See also

References

- S2CID 205209705.

- S2CID 4253007.

- ^ Bansal M (2003). "DNA structure: Revisiting the Watson-Crick double helix". Current Science. 85 (11): 1556–1563.

- PMID 12657780.

- ^

- ^

- ^ PMID 11296253.

- ^ S2CID 213577.

- S2CID 10908125.

- S2CID 4336795.

- ^

- ^

- S2CID 40791601.

- ^ PMID 21109672.

- ^ S2CID 231195473.

- ^ S2CID 2462025.

- PMID 11306347.

- PMID 10966771.

- .

- ^ PMID 790568.

- ^ "Douglas H. Turner". Turner’s rules. Department of Chemistry, University of Rochester.

- PMID 7524072.

- PMID 8085157.

- ^ S2CID 38185676.

- S2CID 16577145.

- PMID 9739090.

- S2CID 4359811.

- S2CID 4316391.

- ^ PMID 37591937.

- PMID 16449200.

- PMID 27609897.

- ^

- PMID 12450393.

- PMID 10872451.

- PMID 9067606.

- PMID 15209494.

- PMID 22605553.

- ISBN 0-85404-654-2.

- ^ PMID 7510342.

- PMID 2258934.

- ^

- PMID 11296253.

- PMID 10481006.

- S2CID 4400869.

- PMID 10458781.

- PMID 12096903.

- .

- PMID 1989074.

- S2CID 42008484.

- PMID 22210339.

- PMID 8939748.

- PMID 9195889.

- PMID 10653698.

- PMID 11574672.

- PMID 7737132.

- PMID 8461289.

- S2CID 4253007.

- S2CID 40989800.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 5279525.

- S2CID 40621440.

- S2CID 17674600.

- PMID 358197.

- S2CID 21563490.

- S2CID 4333072.