Rhythm changes

Rhythm changes is a common 32-

This pattern, "one of the most common vehicles for improvisation,"

History

This progression's endurance in popularity is largely due to its extensive use by early

For contemporary musicians, mastery of the 12-bar blues and rhythm changes chord progressions are "critical elements for building a jazz repertoire".[8]

Chords

The rhythm changes is a 32-bar AABA form with each section consisting of eight bars, and four 8-bar sections.[9] In roman numeral shorthand, the original chords used in the A section are:

I vi ii V I vi ii V

a 2-bar

I I7 IV iv I V I

In a

The "

The B section is followed by a final A section

Variant versions of changes are common due to the popularity of adding interest with

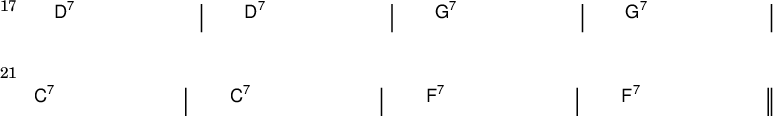

An even more adventurous bebop-style substitution is to convert C7 | C7 | F7 | F7 to Gm7 | C7 | Cm7 | F7, and then to further develop this substitution by changing this to Am7 D7 | Gm7 C7 | Dm7 G7 | Cm7 F7.

Examples

The following is a partial list of songs based on the rhythm changes:

- "Anthropology" (Charlie Parker/Dizzy Gillespie)[7]

- "Cotton Tail" (Duke Ellington)[3][4]

- "Crazeology" (Benny Harris)[13]

- "Dexterity" (Charlie Parker)[7]

- "The Eternal Triangle" (Sonny Stitt)[13]

- "Fungiimama" (Blue Mitchell)

- "Gee" (solo section) (Gustavo Assis-Brasil)[14]

- "Lester Leaps In" (Lester Young)[6]

- "Moose the Mooche" (Charlie Parker)[6]

- "Oleo" (Sonny Rollins)[7]

- ”Passport” (Charlie Parker)[6]

- ”O Latido do cachorro” (David Feldman (musician))

- "Rhythm-A-Ning" (Thelonious Monk)[6]

- "The Serpent's Tooth" (Miles Davis)[13]

- "Steeplechase" (Charlie Parker)[7]

- "Straighten Up and Fly Right" (Nat King Cole)[6]

- "The Theme" (Miles Davis)[13]

- "Tiptoe" (Thad Jones)[6]

The component A and B sections of rhythm changes were also sometimes used for other tunes. For instance, Charlie Parker's "Scrapple from the Apple" and Juan Tizol's "Perdido" both use a different progression for the A section while using the rhythm changes bridge.[15] "Scrapple from the Apple" uses the chord changes of "Honeysuckle Rose" for the A section but replaces the B section with III7–VI7–II7–V7.

Other tunes use the A section of "Rhythm" but have a different bridge. Tadd Dameron's "Good Bait" uses the A section of the Rhythm changes but a different progression for the bridge.[16]

See also

References

- ^ Spitzer (2001), p. 68.

- ISBN 9780739031728.

- ^ a b "Duke Ellington the Man and His Music", p.20. Luvenia A. George. Music Educators Journal, Vol. 85, No. 6 (May, 1999), pp. 15–21. Published by: MENC: The National Association for Music Education.

- ^ ISBN 0-691-12357-8.

- ^ Rust, Brian, Jazz and Ragtime Records, 1897–1942 Archived 2009-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, Mainspring Press, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Rhythm Changes," MoneyChords (angelfire.com). Includes an extensive listing of tunes utilizing these chord changes.

- ^ ISBN 0-7866-5328-0.

- ISBN 0-634-01655-5.

- ^ Spitzer (2001), p. 81.

- ^ ISBN 9781576233412.

- ISBN 9781601981721.

- ISBN 9780634086786.

- ^ OCLC 34280067.

- ^ [1], All About Jazz website, by William James

- ^ Spitzer (2001), p. 71.

- ^ Spitzer (2001), p. 72.

Further reading

- R., Ken (2012). DOG EAR Tritone Substitution for Jazz Guitar, Amazon Digital Services, ASIN: B008FRWNIW