Set theory (music)

Musical set theory provides concepts for categorizing

One branch of musical set theory deals with collections (

Comparison with mathematical set theory

Although musical set theory is often thought to involve the application of mathematical

Moreover, musical set theory is more closely related to group theory and combinatorics than to mathematical set theory, which concerns itself with such matters as, for example, various sizes of infinitely large sets. In combinatorics, an unordered subset of n objects, such as pitch classes, is called a combination, and an ordered subset a permutation. Musical set theory is better regarded as an application of combinatorics to music theory than as a branch of mathematical set theory. Its main connection to mathematical set theory is the use of the vocabulary of set theory to talk about finite sets.

Types of sets

The fundamental concept of musical set theory is the (musical) set, which is an unordered collection of pitch classes.[4] More exactly, a pitch-class set is a numerical representation consisting of distinct integers (i.e., without duplicates).[5] The elements of a set may be manifested in music as simultaneous chords, successive tones (as in a melody), or both.[citation needed] Notational conventions vary from author to author, but sets are typically enclosed in curly braces: {},[6] or square brackets: [].[5]

Some theorists use angle brackets ⟨ ⟩ to denote ordered sequences,[7] while others distinguish ordered sets by separating the numbers with spaces.[8] Thus one might notate the unordered set of pitch classes 0, 1, and 2 (corresponding in this case to C, C♯, and D) as {0,1,2}. The ordered sequence C-C♯-D would be notated ⟨0,1,2⟩ or (0,1,2). Although C is considered zero in this example, this is not always the case. For example, a piece (whether tonal or atonal) with a clear pitch center of F might be most usefully analyzed with F set to zero (in which case {0,1,2} would represent F, F♯ and G. (For the use of numbers to represent notes, see pitch class.)

Though set theorists usually consider sets of equal-tempered pitch classes, it is possible to consider sets of pitches, non-equal-tempered pitch classes,[citation needed] rhythmic onsets, or "beat classes".[9][10]

Two-element sets are called

Basic operations

The basic operations that may be performed on a set are

Some authors consider the operations of

Operations on ordered sequences of pitch classes also include transposition and inversion, as well as retrograde and rotation. Retrograding an ordered sequence reverses the order of its elements. Rotation of an ordered sequence is equivalent to cyclic permutation.

Transposition and inversion can be represented as elementary arithmetic operations. If x is a number representing a pitch class, its transposition by n semitones is written Tn = x + n mod 12. Inversion corresponds to

Equivalence relation

"For a relation in set S to be an equivalence relation [in algebra], it has to satisfy three conditions: it has to be reflexive ..., symmetrical ..., and transitive ...".[16] "Indeed, an informal notion of equivalence has always been part of music theory and analysis. PC set theory, however, has adhered to formal definitions of equivalence."[17]

Transpositional and inversional set classes

Two transpositionally related sets are said to belong to the same transpositional set class (Tn). Two sets related by transposition or inversion are said to belong to the same transpositional/inversional set class (inversion being written TnI or In). Sets belonging to the same transpositional set class are very similar-sounding; while sets belonging to the same transpositional/inversional set class could include two chords of the same type but in different keys, which would be less similar in sound but obviously still a bounded category. Because of this, music theorists often consider set classes basic objects of musical interest.

There are two main conventions for naming equal-tempered set classes. One, known as the Forte number, derives from Allen Forte, whose The Structure of Atonal Music (1973), is one of the first works in musical set theory. Forte provided each set class with a number of the form c–d, where c indicates the cardinality of the set and d is the ordinal number.[18] Thus the chromatic trichord {0, 1, 2} belongs to set-class 3–1, indicating that it is the first three-note set class in Forte's list.[19] The augmented trichord {0, 4, 8}, receives the label 3–12, which happens to be the last trichord in Forte's list.

The primary criticisms of Forte's nomenclature are: (1) Forte's labels are arbitrary and difficult to memorize, and it is in practice often easier simply to list an element of the set class; (2) Forte's system assumes equal temperament and cannot easily be extended to include diatonic sets, pitch sets (as opposed to pitch-class sets),

Western tonal music for centuries has regarded major and minor, as well as chord inversions, as significantly different. They generate indeed completely different physical objects. Ignoring the physical reality of sound is an obvious limitation of atonal theory. However, the defense has been made that theory was not created to fill a vacuum in which existing theories inadequately explained tonal music. Rather, Forte's theory is used to explain atonal music, where the composer has invented a system where the distinction between {0, 4, 7} (called 'major' in tonal theory) and its inversion {0, 3, 7} (called 'minor' in tonal theory) may not be relevant.

The second notational system labels sets in terms of their

Since transpositionally related sets share the same normal form, normal forms can be used to label the Tn set classes.

To identify a set's Tn/In set class:

- Identify the set's Tn set class.

- Invert the set and find the inversion's Tn set class.

- Compare these two normal forms to see which is most "left packed."

The resulting set labels the initial set's Tn/In set class.

Symmetries

The number of distinct operations in a system that map a set into itself is the set's

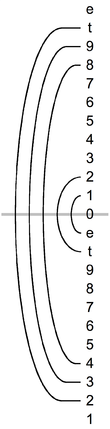

Transpositionally symmetrical sets either divide the octave evenly, or can be written as the union of equally sized sets that themselves divide the octave evenly. Inversionally symmetrical chords are invariant under reflections in pitch class space. This means that the chords can be ordered cyclically so that the series of intervals between successive notes is the same read forward or backward. For instance, in the cyclical ordering (0, 1, 2, 7), the interval between the first and second note is 1, the interval between the second and third note is 1, the interval between the third and fourth note is 5, and the interval between the fourth note and the first note is 5.[24]

One obtains the same sequence if one starts with the third element of the series and moves backward: the interval between the third element of the series and the second is 1; the interval between the second element of the series and the first is 1; the interval between the first element of the series and the fourth is 5; and the interval between the last element of the series and the third element is 5. Symmetry is therefore found between T0 and T2I, and there are 12 sets in the Tn/TnI equivalence class.[24]

See also

References

- ^ Schuijer 2008, 99.

- ^ Hanson 1960.

- ^ Forte 1973.

- ^ Rahn 1980, 27.

- ^ a b Forte 1973, 3.

- ^ Rahn 1980, 28.

- ^ Rahn 1980, 21, 134.

- ^ Forte 1973, 60–61.

- ^ Warburton 1988, 148.

- ^ Cohn 1992, 149.

- ^ Rahn 1980, 140.

- ^ Forte 1973, 73–74.

- ^ Forte 1973, 21.

- ^ Hanson 1960, 22.

- ^ Cohen 2004, 33.

- ^ Schuijer 2008, 29–30.

- ^ Schuijer 2008, 85.

- ^ Forte 1973, 12.

- ^ Forte 1973, 179–181.

- ^ Rahn 1980, 33–38.

- ^ Rahn 1980, 90.

- ^ Alegant 2001, 5.

- ^ Rahn 1980, 91.

- ^ a b Rahn 1980, 148.

Sources

- Alegant, Brian. 2001. "Cross-Partitions as Harmony and Voice Leading in Twelve-Tone Music". Music Theory Spectrum 23, no. 1 (Spring): 1–40.

- Cohen, Allen Laurence. 2004. Howard Hanson in Theory and Practice. Contributions to the Study of Music and Dance 66. Westport, Conn. and London: Praeger. ISBN 0-313-32135-3.

- Cohn, Richard. 1992. "Transpositional Combination of Beat-Class Sets in Steve Reich's Phase-Shifting Music". Perspectives of New Music 30, no. 2 (Summer): 146–177.

- ISBN 0-300-02120-8(pbk).

- Hanson, Howard. 1960. Harmonic Materials of Modern Music: Resources of the Tempered Scale. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- ISBN 0-02-873160-3.

- Schuijer, Michiel. 2008. Analyzing Atonal Music: Pitch-Class Set Theory and Its Contexts. ISBN 978-1-58046-270-9.

- Warburton, Dan. 1988. "A Working Terminology for Minimal Music". Intégral 2:135–159.

Further reading

- ISBN 0-8258-4594-7.

- ISBN 978-0-19-531712-1.

- Lewin, David. 1987. Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531713-8.

- ISBN 0-300-03684-1.

- ISBN 0-520-03387-6)

- Starr, Daniel. 1978. "Sets, Invariance and Partitions". Journal of Music Theory 22, no. 1 (Spring): 1–42.

- Straus, Joseph N. 2005. Introduction to Post-Tonal Theory, third edition. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-189890-6.

External links

- Tucker, Gary (2001) "A Brief Introduction to Pitch-Class Set Analysis", Mount Allison University Department of Music.

- Nick Collins "Uniqueness of pitch class spaces, minimal bases and Z partners", Sonic Arts.

- "Twentieth Century Pitch Theory: Some Useful Terms and Techniques", Form and Analysis: A Virtual Textbook.

- Solomon, Larry (2005). "Set Theory Primer for Music", SolomonMusic.net.

- Kelley, Robert T (2001). "Introduction to Post-Functional Music Analysis: Post-Functional Theory Terminology", RobertKelleyPhd.com.

- Kelley, Robert T (2002). "Introduction to Post-Functional Music Analysis: Set Theory, The Matrix, and the Twelve-Tone Method".

- "SetClass View (SCv)", Flexatone.net. An athenaCL netTool for on-line, web-based pitch class analysis and reference.

- Tomlin, Jay. "All About Set Theory". JayTomlin.com.

- "Java Set Theory Machine" or Calculator

- Kaiser, Ulrich. "Pitch Class Set Calculator", musikanalyse.net. (in German)

- "Pitch-Class Set Theory and Perception", Ohio-State.edu.

- "Software Tools for Composers", ComposerTools.com. Javascript PC Set calculator, two-set relationship calculators, and theory tutorial.

- "PC Set Calculator", MtA.Ca.

- Taylor, Stephen Andrew. "SetFinder", stephenandrewtaylor.net. Pitch class set library and prime form calculator.