Tone row

In

History and usage

Tone rows are the basis of Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique and most types of serial music. Tone rows were widely used in 20th-century contemporary music, like Dmitri Shostakovich's use of twelve-tone rows, "without dodecaphonic transformations."[4][5]

A tone row has been identified in the A minor prelude,

Theory and compositional techniques

Tone rows are designated by letters and subscript numbers (e.g.: RI11, which may also appear as RI11 or RI–11). The numbers indicate the initial (P or I) or final (R or RI) pitch-class number of the given row form, most often with c = 0.

- "P" indicates prime, a forward-directed right-side up form.

- "I" indicates inversion, a forward-directed upside-down form.

- "R" indicates retrograde, a backwards right-side up form.

- "RI" indicates retrograde-inversion, a backwards upside-down form.

- Transposition is indicated by a T number, for example P8 is a T(4) transposition of P4.[11][further explanation needed]

A twelve-tone composition will take one or more tone rows, called the "prime form", as its basis plus their transformations (inversion, retrograde, retrograde inversion, as well as transposition; see twelve-tone technique for details). These forms may be used to construct a melody in a straightforward manner as in Schoenberg's Piano Suite Op. 25 Minuet Trio, where P-0 is used to construct the opening melody and later varied through transposition, as P-6, and also in articulation and dynamics. It is then varied again through inversion, untransposed, taking form I-0. However, rows may be combined to produce melodies or harmonies in more complicated ways, such as taking successive or multiple pitches of a melody from two different row forms, as described at twelve-tone technique.

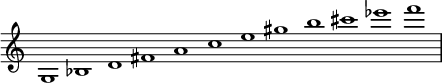

Initially, Schoenberg required the avoidance of suggestions of tonality—such as the use of consecutive imperfect consonances (thirds or sixths)—when constructing tone rows, reserving such use for the time when the dissonance is completely emancipated. Alban Berg, however, sometimes incorporated tonal elements into his twelve-tone works. The main tone row of his Violin Concerto hints at this tonality:

This tone row consists of alternating minor and major

Some tone rows have a high degree of internal organization. An example is the tone row from Anton Webern's Concerto for Nine Instruments Op. 24, shown below.[12]

In this tone row, if the first three notes are regarded as the "original" cell, then the next three are its retrograde inversion, the next three are retrograde, and the last three are its inversion. A row created in this manner, through variants of a trichord or tetrachord called the generator, is called a derived row.

The tone rows of many of Webern's other late works are similarly intricate. The tone row for Webern's String Quartet Op. 28 is based on the BACH motif (B♭, A, C, B♮) and is composed of three tetrachords:

The "set-complex" is the forty-eight forms of the set generated by stating each "aspect" or transformation on each pitch class.[2]

The all-interval twelve-tone row is a tone row arranged so that it contains one instance of each interval within the octave, 0 through 11.

The "total chromatic" (or "aggregate") is the set of all twelve pitch classes. An "array" is a succession of aggregates.[13] The term is also used to refer to lattices.

An aggregate may be achieved through complementation or combinatoriality, such as with hexachords.

A "secondary set" is a tone row which is derived from or, "results from the reversed coupling of hexachords", when a given row form is immediately repeated.[14][15] For example, the row form consisting of two hexachords:

0 1 2 3 4 5 / 6 7 8 9 t e

when repeated immediately results in the following succession of two aggregates, in the middle of which is a new and complete aggregate beginning with the second hexachord:

0 1 2 3 4 5 / 6 7 8 9 t e / 0 1 2 3 4 5 / 6 7 8 9 t e secondary set: [6 7 8 9 t e / 0 1 2 3 4 5]

A "weighted aggregate" is an aggregate in which the twelfth pitch does not appear until at least one pitch has appeared at least twice, supplied by segments of different set forms.[16] It seems to have been first used in Milton Babbitt's String Quartet No. 4. An aggregate may be vertically or horizontally weighted. An "all-partition array" is created by combining a collection of hexachordally combinatorial arrays.[17]

Nonstandard tone rows

Schoenberg specified many strict rules and desirable guidelines for the construction of tone rows such as number of notes and intervals to avoid. Tone rows that depart from these guidelines include the above tone row from Berg's Violin Concerto which contains triads and tonal emphasis, and the tone row below from Luciano Berio's Nones which contains a repeated note making it a 'thirteen-tone row':

Igor Stravinsky used a five-tone row, chromatically filling out the space of a major third centered tonally on C (C–E), in one of his early serial compositions, In memoriam Dylan Thomas.

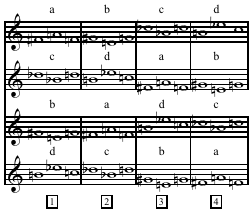

In his twelve-tone practice, Stravinsky preferred the inverse-retrograde (IR) to the retrograde-inverse (RI),[21][22][23] as for example in his Requiem Canticles:

See also

References

- ^ Leeuw 2005, 154. Italics original.

- ^ a b Perle 1977, 3

- ^ Leeuw 2005, 174.

- ISBN 9781409472025.

- ^ Stephen C. Brown, "Twelve-Tone Rows and Aggregate Melodies in the Music of Shostakovich," Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 59, No. 2 (Fall 2015): 191–234.

- ^ "Discovery Reveals Bach's Postmodern Side". Weekend Edition Sunday, NPR, 6 September 2009.

- ^ Keller 1955, 14–21.

- ^ Keller 1955, 22–23.

- ^ Keller 1955, 23.

- ^ Leeuw 2005, 158.

- ^ Perle 1996, 3.

- ^ Whittall 2008, 97.

- ^ a b Whittall 2008, 271

- ^ Perle 1977, 100.

- ^ Perle 1996, 20.

- ^ Haimo 1990, 183.

- ISBN 9781580463225.

- ^ Leeuw 2005, 166.

- ^ Whittall 2008, 127.

- ^ Whittall 2008, 195.

- ^ Claudio Spies, "Notes on Stravinsky's Abraham and Isaac", Perspectives of New Music 3, no. 2 (Spring–Summer 1965): 104–126, citation on 118.

- ^ Joseph N. Strauss, "Stravinsky's Serial 'Mistakes'", The Journal of Musicology 17, no. 2 (Spring 1999): 231–271, citation on 242.

- ^ a b Whittall 2008, 139

- ^ a b Leeuw 2005, pp. 176–177

- ^ John Fonville, "Ben Johnston's Extended Just Intonation: A Guide for Interpreters", Perspectives of New Music 29, no. 2 (Summer 1991): 106–137, citation on 127.

Sources

- Haimo, Ethan (1990). Schoenberg's Serial Odyssey: The Evolution of his Twelve-Tone Method, 1914–1928. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780193152601.

- .

- ISBN 90-313-0244-9.

- ISBN 0-520-03395-7.

- Perle, George (1996). Twelve-Tone Tonality (2nd, revised and expanded ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20142-6.

- OCLC 237192271.

Further reading

- Hunter, David J.; Hippel, Paul T. von (February 2003). "How Rare Is Symmetry in Musical 12-Tone Rows?". JSTOR 3647771.

External links

- Database on tone rows and tropes, Harald Fripertinger, Peter Lackner