Shigella dysenteriae

| Shigella dysenteriae | |

|---|---|

| |

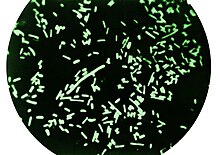

| Dark-field microscopy revealing Shigella dysenteriae bacteria | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Enterobacterales |

| Family: | Enterobacteriaceae |

| Genus: | Shigella |

| Species: | S. dysenteriae

|

| Binomial name | |

| Shigella dysenteriae (Shiga 1897)

Castellani & Chalmers 1919 | |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2010) |

Shigella dysenteriae is a species of the rod-shaped

Signs and symptoms

The most commonly observed signs associated with Shigella dysentery include

Diagnosis

Since the typical fecal specimen is not sterile, the use of selective plates is mandatory. XLD agar, DCA agar, or Hektoen enteric agar are inoculated; all give colorless colonies as the organism is not a lactose fermenter. Inoculation of a TSI slant shows an alkaline slant and acidic, but with no gas, or H

2S production. Following incubation on SIM, the culture appears nonmotile with no H

2S production. Addition of Kovac's reagent to the SIM tube following growth typically indicates no indole formation (serotypes 2, 7, and 8 produce indole[5]).

Mannitol tests yields negative results.[4] Ornithine Decarboxylase tests yield negative results.[4]

Treatment

Treatment for shigellosis, independent of the subspecies, requires an

Epidemiology

Shigella infections may be contracted by a lack of monitoring of water and food quality, unsanitary cooking conditions and improper hygiene practices.[6] S. dysenteriae spreads through contaminated water and food, causes minor

Contamination is often caused by bacteria on unwashed hands during food preparation, or soiled hands reaching the mouth.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ISBN 978-0-357-62624-5.

- ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c Ryan, Kenneth James (2018). "Chapter 33: Enterobacteriaceae". Sherris Medical Microbiology (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional Med/Tech.

- ^ a b c d e f Karen C. Carroll; Jeffery A. Hobden; Steve Miller; Stephen A. Morse; Timothy A. Mietzner; Barbara Detrick; Thomas G. Mitchell; James H. McKerrow; Judy A. Sakanari (2016). "Chapter 15: Enteric Gram-Negative Rods (Enterobacteriaceae)". Jawetz, Melnick, & Adelberg's Medical Microbiology (27 ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional Med/Tech.

- )

- ^ Justin L. Kaplan MD; Robert S. Porter MD (2018). Larry M. Bush,MD (ed.). Merck Manual Consumer Version.

- PMID 15493821.

External links

- Shigella dysenteriae at the NCBI Taxonomy Browser

- Type strain of Shigella dysenteriae at BacDive, the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase