Andachtsbilder

Andachtsbilder (singular Andachtsbild, German for devotional image) is a German term often used in English in art history for Christian devotional images designed as aids for prayer or contemplation. The images "generally show holy figures extracted from a narrative context to form a highly focused, and often very emotionally powerful, vignette".[1]

The term is especially used of Northern

Subjects and genres

Traditional subjects from the narrative of the

The traditional Ecce Homo is a very crowded scene, in which the figure of Christ is often less prominent than those of his captors, but in the andachtsbilder versions the other figures and complex architectural background have vanished, leaving only Christ, with a plain background in most painted versions (see the example by Antonello da Messina in the gallery below).[4][b]

Andachtsbilder have a strong emphasis on the

Scope

Sculptures

The term was first devised for a group of mainly sculptural subjects, including the Pietà and Pensive Christ, that were thought to have emerged in convents in south-western Germany in the 14th century, although their history is now believed to be more complicated.[6]

In churches such images were often given a

Paintings, carvings, and prints

The term is often used specifically for small works intended for personal contemplation in the home. By the 15th century the emerging urban middle classes of Northern Europe were increasingly able to afford small paintings or carvings. The depiction was often very "close-up", with a half-length figure occupying nearly the whole picture space.[8] Andachtsbilder subjects were also very common in prints. However larger works for churches or outdoor display are also covered by the term.

By the mid-15th century andachtsbilder were influencing large monumental works, a process James Snyder discusses in relation to major works such as

The art historian

Gallery

-

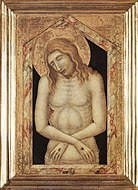

An early Man of Sorrows by the Italian artist Pietro Lorenzetti, c. 1330

-

Dominican friar, Barna da Siena, 1330–1350

-

Meister Francke, c. 1435.[12]

-

Pensive Christ with the Arma Christi, German, 1450–60

-

Engraving of c. 1460 by Master E. S. of the Man of Sorrows with the Arma Christi

-

One of several versions of theEcce Homo by Antonello da Messina, who was influenced by Early Netherlandish painting, c. 1473

-

Instruments of the Passionare expanded, as here, to include heads and disembodied hands of the persecutors.

-

Memling, 1470, showing a typically gentler and less emotive Flemish style.

-

The Venetian Giovanni Bellini painted several andachtsbilder subjects, typically, as here, pulling back somewhat compared to Northern "close-up" treatments.

-

A highly original composition by Andrea Mantegna of the laying-out of the dead Christ, c. 1490.

-

Ecce Homo by Andrea Mantegna, c. 1500, avoids Northern emotionalism, but retains the "close up" composition.

-

Polish crucifix of c. 1500, showing the andachtsbilder style

Notes

- ^ Snyder (1985) and, much more fully, Schiller (1972) cover these passim, see their indexes. Schiller's translator always translates the German term to "devotional images" etc.

- ^ There are other small types with just two or three figures - see the Mantegna in the gallery.

- National Museum, Warsaw

References

- ^ Ross (1996), p. 12.

- ^ Discussed by Snyder (1985), pp. 176–78

- ^ Schiller (1972), pp. 146–148.

- ^ Schiller (1972), pp. 75–76.

- ^ Schiller (1972), pp. 179–180, 190–191, 197–198.

- ^ a b Hamburger (1997), p. 3.

- ^ Schiller (1972), p. 180–181.

- ^ Elkins (2001), pp. 154–161.

- ^ Snyder (1985), pp. 128.

- ^ Snyder (1985), pp. 348–50.

- ^ Snyder (1985), pp. 306.

- ^ Discussed by Snyder (1985), p. 86

Sources

- Elkins, James (2001). Pictures and Tears: A History of People Who Have Cried in Front of Paintings. New York: Routledge. OCLC 48025999. google books

- Hamburger, Jeffrey F. (1997). Nuns as artists: the visual culture of a medieval convent. Berkeley: University of California Press. OCLC 44962917. Google books

- Ross, Leslie (1996). Medieval Art: a topical dictionary. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. OCLC 70764987. Google books

- OCLC 237920.

- OCLC 10799841.

![Man of Sorrows by the North German artist Meister Francke, c. 1435.[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/be/Meister_Francke_003.jpg/137px-Meister_Francke_003.jpg)