Christianity

| Christianity | |

|---|---|

Jesus Christ | |

| Origin | 1st century AD Judaea, Roman Empire |

| Separated from | Second Temple Judaism[note 1] |

| Separations | Unitarian Universalism[7] |

| Number of followers | c. 2.4 billion |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Christianity (

Christianity remains culturally diverse in its Western and Eastern branches, and doctrinally diverse concerning justification and the nature of salvation, ecclesiology, ordination, and Christology. The creeds of various Christian denominations generally hold in common Jesus as the Son of God—the Logos incarnated—who ministered, suffered, and died on a cross, but rose from the dead for the salvation of humankind; and referred to as the gospel, meaning the "good news". The four canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John describe Jesus's life and teachings, with the Old Testament as the gospels' respected background.

Christianity

The six major

Etymology

Early Jewish Christians referred to themselves as 'The Way' (

Beliefs

While Christians worldwide share basic convictions, there are differences of interpretations and opinions of the Bible and sacred traditions on which Christianity is based.[24]

Creeds

Concise doctrinal statements or confessions of religious beliefs are known as

The

This particular creed was developed between the 2nd and 9th centuries. Its central doctrines are those of the

- Belief in Holy Spirit

- The death, descent into hell, resurrection and ascension of Christ

- The holiness of the Church and the communion of saints

- Christ's second coming, the Day of Judgement and salvationof the faithful

The

The

The Athanasian Creed, received in the Western Church as having the same status as the Nicene and Chalcedonian, says: "We worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; neither confounding the Persons nor dividing the Substance".[33]

Most Christians (

Certain

Jesus

The central tenet of Christianity is the belief in

While there have been many

According to the

Death and resurrection

Christians consider the resurrection of Jesus to be the cornerstone of their faith (see

The

The death and resurrection of Jesus are usually considered the most important events in Christian theology, partly because they demonstrate that Jesus has power over life and death and therefore has the authority and power to give people eternal life.[49]

Christian churches accept and teach the

Salvation

"For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life".

— John 3:16, NIV[57]

Modern Christian churches tend to be much more concerned with how humanity can be

Christians differ in their views on the extent to which individuals' salvation is pre-ordained by God. Reformed theology places distinctive emphasis on grace by teaching that individuals are

Trinity

Trinity refers to the teaching that the one God

The

According to this doctrine, God is not divided in the sense that each person has a third of the whole; rather, each person is considered to be fully God (see

The Greek word trias[78][note 5] is first seen in this sense in the works of Theophilus of Antioch; his text reads: "of the Trinity, of God, and of His Word, and of His Wisdom".[82] The term may have been in use before this time; its Latin equivalent,[note 5] trinitas,[80] appears afterwards with an explicit reference to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, in Tertullian.[83][84] In the following century, the word was in general use. It is found in many passages of Origen.[85]

Trinitarianism

Trinitarianism denotes Christians who believe in the concept of the Trinity. Almost all Christian denominations and churches hold Trinitarian beliefs. Although the words "Trinity" and "Triune" do not appear in the Bible, beginning in the 3rd century theologians developed the term and concept to facilitate apprehension of the New Testament teachings of God as being Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Since that time, Christian theologians have been careful to emphasize that Trinity does not imply that there are three gods (the antitrinitarian heresy of Tritheism), nor that each hypostasis of the Trinity is one-third of an infinite God (partialism), nor that the Son and the Holy Spirit are beings created by and subordinate to the Father (Arianism). Rather, the Trinity is defined as one God in three persons.[86]

Nontrinitarianism

Nontrinitarianism (or antitrinitarianism) refers to theology that rejects the doctrine of the Trinity. Various nontrinitarian views, such as

Eschatology

The end of things, whether the end of an individual life, the end of the age, or the end of the world, broadly speaking, is Christian eschatology; the study of the destiny of humans as it is revealed in the Bible. The major issues in Christian eschatology are the

Christians believe that the second coming of Christ will occur at the

Death and afterlife

Most Christians believe that human beings experience divine judgment and are rewarded either with eternal life or

In the Catholic branch of Christianity, those who die in a state of grace, i.e., without any mortal sin separating them from God, but are still imperfectly purified from the effects of sin, undergo purification through the intermediate state of purgatory to achieve the holiness necessary for entrance into God's presence.[95] Those who have attained this goal are called saints (Latin sanctus, "holy").[96]

Some Christian groups, such as Seventh-day Adventists, hold to mortalism, the belief that the human soul is not naturally immortal, and is unconscious during the intermediate state between bodily death and resurrection. These Christians also hold to Annihilationism, the belief that subsequent to the final judgement, the wicked will cease to exist rather than suffer everlasting torment. Jehovah's Witnesses hold to a similar view.[97]

Practices

Depending on the specific

Communal worship

, and his description remains relevant to the basic structure of Christian liturgical worship:And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen; and there is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given, and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons. And they who are well to do, and willing, give what each thinks fit; and what is collected is deposited with the president, who succours the orphans and widows and those who, through sickness or any other cause, are in want, and those who are in bonds and the strangers sojourning among us, and in a word takes care of all who are in need.[104]

Thus, as Justin described, Christians assemble for communal worship typically on Sunday, the day of the resurrection, though other liturgical practices often occur outside this setting. Scripture readings are drawn from the Old and New Testaments, but especially the gospels.

Nearly all forms of worship incorporate the Eucharist, which consists of a meal. It is reenacted in accordance with Jesus' instruction at the Last Supper that his followers do in remembrance of him as when he gave his disciples

Sacraments or ordinances

And this food is called among us Eukharistia [the Eucharist], of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Savior, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.

In Christian belief and practice, a sacrament is a

The most conventional functional definition of a sacrament is that it is an outward sign, instituted by Christ, that conveys an inward, spiritual grace through Christ. The two most widely accepted sacraments are

Taken together, these are the

In addition to this, the

-

A penitent confessing his sins in a Ukrainian Catholic church

-

AMethodist minister celebrating the Eucharist

-

Confirmation being administered in an Anglican church

-

Eastern Orthodoxtradition

-

Syro-Malabar Catholic Church

-

Service of the Sacrament ofHoly Unctionserved on Great and Holy Wednesday

Liturgical calendar

Catholics, Eastern Christians, Lutherans, Anglicans and other traditional Protestant communities frame worship around the liturgical year.[120] The liturgical cycle divides the year into a series of seasons, each with their theological emphases, and modes of prayer, which can be signified by different ways of decorating churches, colors of paraments and vestments for clergy,[121] scriptural readings, themes for preaching and even different traditions and practices often observed personally or in the home.

Western Christian liturgical calendars are based on the cycle of the

Symbols

Most Christian denominations have not generally practiced

The cross, today one of the most widely recognized symbols, was used by Christians from the earliest times.[125][126] Tertullian, in his book De Corona, tells how it was already a tradition for Christians to trace the sign of the cross on their foreheads.[127] Although the cross was known to the early Christians, the crucifix did not appear in use until the 5th century.[128]

Among the earliest Christian symbols, that of the fish or Ichthys seems to have ranked first in importance, as seen on monumental sources such as tombs from the first decades of the 2nd century.[129] Its popularity seemingly arose from the Greek word ichthys (fish) forming an acrostic for the Greek phrase Iesous Christos Theou Yios Soter (Ἰησοῦς Χριστός, Θεοῦ Υἱός, Σωτήρ),[note 8] (Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior), a concise summary of Christian faith.[129]

Other major Christian symbols include the

Baptism

Baptism is the ritual act, with the use of water, by which a person is admitted to membership of the

Prayer

"... 'Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name. Your kingdom come. Your will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Give us today our daily bread. Forgive us our debts, as we also forgive our debtors. Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil'".

— The Lord's Prayer, Matthew 6:9–13, EHV[145]

In the

In the second century

The Apostolic Tradition directed that the sign of the cross be used by Christians during the minor exorcism of baptism, during ablutions before praying at fixed prayer times, and in times of temptation.[153]

Intercessory prayer is prayer offered for the benefit of other people. There are many intercessory prayers recorded in the Bible, including prayers of the

The ancient church, in both

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church: "Prayer is the raising of one's mind and heart to God or the requesting of good things from God".[161] The Book of Common Prayer in the Anglican tradition is a guide which provides a set order for services, containing set prayers, scripture readings, and hymns or sung Psalms.[162] Frequently in Western Christianity, when praying, the hands are placed palms together and forward as in the feudal commendation ceremony. At other times the older orans posture may be used, with palms up and elbows in.

Scriptures

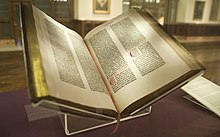

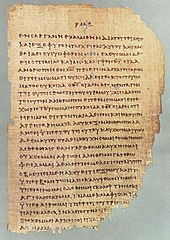

Christianity, like other religions, has adherents whose beliefs and biblical interpretations vary. Christianity regards the biblical canon, the Old Testament and the New Testament, as the inspired word of God. The traditional view of inspiration is that God worked through human authors so that what they produced was what God wished to communicate. The Greek word referring to inspiration in 2 Timothy 3:16 is theopneustos, which literally means "God-breathed".[163]

Some believe that divine inspiration makes present Bibles inerrant. Others claim inerrancy for the Bible in its original manuscripts, although none of those are extant. Still others maintain that only a particular translation is inerrant, such as the King James Version.[164][165][166] Another closely related view is biblical infallibility or limited inerrancy, which affirms that the Bible is free of error as a guide to salvation, but may include errors on matters such as history, geography, or science.

The canon of the Old Testament accepted by Protestant churches, which is only the

Some denominations have

Catholic interpretation

In antiquity, two schools of exegesis developed in

Catholic theology distinguishes two senses of scripture: the literal and the spiritual.[171]

The literal sense of understanding scripture is the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture. The spiritual sense is further subdivided into:

- The allegorical sense, which includes parting of the Red Sea being understood as a "type" (sign) of baptism.[172]

- The moral sense, which understands the scripture to contain some ethical teaching.

- The anagogical sense, which applies to eschatology, eternity and the consummation of the world.

Regarding exegesis, following the rules of sound interpretation, Catholic theology holds:

- The injunction that all other senses of sacred scripture are based on the literal[173][174]

- That the historicity of the Gospels must be absolutely and constantly held[175]

- That scripture must be read within the "living Tradition of the whole Church"[176] and

- That "the task of interpretation has been entrusted to the bishops in communion with the successor of Peter, the Bishop of Rome".[177]

Protestant interpretation

Qualities of Scripture

Many Protestant Christians, such as Lutherans and the Reformed, believe in the doctrine of sola scriptura—that the Bible is a self-sufficient revelation, the final authority on all Christian doctrine, and revealed all truth necessary for salvation;[178][179] other Protestant Christians, such as Methodists and Anglicans, affirm the doctrine of prima scriptura which teaches that Scripture is the primary source for Christian doctrine, but that "tradition, experience, and reason" can nurture the Christian religion as long as they are in harmony with the Bible.[178][180] Protestants characteristically believe that ordinary believers may reach an adequate understanding of Scripture because Scripture itself is clear in its meaning (or "perspicuous"). Martin Luther believed that without God's help, Scripture would be "enveloped in darkness".[181] He advocated for "one definite and simple understanding of Scripture".[181] John Calvin wrote, "all who refuse not to follow the Holy Spirit as their guide, find in the Scripture a clear light".[182] Related to this is "efficacy", that Scripture is able to lead people to faith; and "sufficiency", that the Scriptures contain everything that one needs to know to obtain salvation and to live a Christian life.[183]

Original intended meaning of Scripture

Protestants stress the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture, the

History

Early Christianity

Apostolic Age

Christianity developed during the 1st century AD as a

Jewish Christianity soon attracted Gentile God-fearers, posing a problem for its

Ante-Nicene period

This formative period was followed by the early bishops, whom Christians consider the successors of Christ's apostles. From the year 150, Christian teachers began to produce theological and apologetic works aimed at defending the faith. These authors are known as the Church Fathers, and the study of them is called patristics. Notable early Fathers include Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria and Origen.

While

Spread and acceptance in Roman Empire

Christianity spread to

King Tiridates III made Christianity the state religion in Armenia in the early 4th century AD, making Armenia the first officially Christian state.[203][204] It was not an entirely new religion in Armenia, having penetrated into the country from at least the third century, but it may have been present even earlier.[205]

Constantine was also instrumental in the convocation of the

In terms of prosperity and cultural life, the

Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages

With the decline and

Around 500, Christianity was thoroughly integrated into Byzantine and

In the 7th century,

The Middle Ages brought about major changes within the church.

High and Late Middle Ages

In the West, from the 11th century onward, some older cathedral schools became universities (see, for example, University of Oxford, University of Paris and University of Bologna). Previously, higher education had been the domain of Christian cathedral schools or monastic schools (Scholae monasticae), led by monks and nuns. Evidence of such schools dates back to the 6th century AD.[228] These new universities expanded the curriculum to include academic programs for clerics, lawyers, civil servants, and physicians.[229] The university is generally regarded as an institution that has its origin in the Medieval Christian setting.[230][231][232]

Accompanying the rise of the "new towns" throughout Europe,

The Christian Church experienced internal conflict between the 7th and 13th centuries that resulted in a

In the thirteenth century, a new emphasis on Jesus' suffering, exemplified by the Franciscans' preaching, had the consequence of turning worshippers' attention towards Jews, on whom Christians had placed the blame for Jesus' death. Christianity's limited tolerance of Jews was not new—Augustine of Hippo said that Jews should not be allowed to enjoy the citizenship that Christians took for granted—but the growing antipathy towards Jews was a factor that led to the expulsion of Jews from England in 1290, the first of many such expulsions in Europe.[241][242]

Beginning around 1184, following the crusade against

Modern era

Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation

The 15th-century

Other reformers like

Thomas Müntzer, Andreas Karlstadt and other theologians perceived both the Catholic Church and the confessions of the Magisterial Reformation as corrupted. Their activity brought about the Radical Reformation, which gave birth to various Anabaptist denominations.

Partly in response to the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church engaged in a substantial process of reform and renewal, known as the Counter-Reformation or Catholic Reform.[251] The Council of Trent clarified and reasserted Catholic doctrine. During the following centuries, competition between Catholicism and Protestantism became deeply entangled with political struggles among European states.[252]

Meanwhile, the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus in 1492 brought about a new wave of missionary activity. Partly from missionary zeal, but under the impetus of colonial expansion by the European powers, Christianity spread to the Americas, Oceania, East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Throughout Europe, the division caused by the Reformation led to outbreaks of

In the revival of neoplatonism

Post-Enlightenment

In the era known as the

Especially pressing in Europe was the formation of

The combined factors of the formation of nation states and ultramontanism, especially in Germany and the Netherlands, but also in England to a much lesser extent,[268] often forced Catholic churches, organizations, and believers to choose between the national demands of the state and the authority of the Church, specifically the papacy. This conflict came to a head in the First Vatican Council, and in Germany would lead directly to the Kulturkampf.[269]

Christian commitment in Europe dropped as modernity and secularism came into their own,.

Demographics

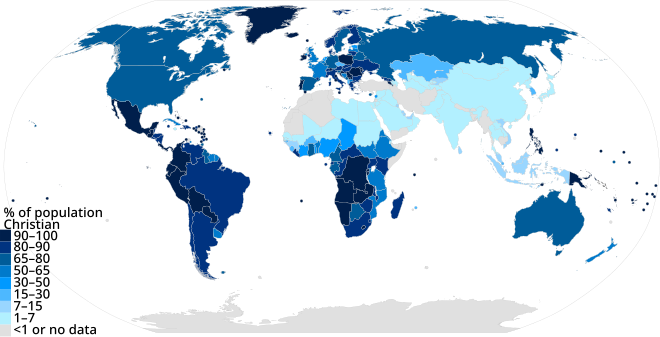

With around 2.4 billion adherents according to a 2020 estimation by

According to some scholars, Christianity ranks at first place in net gains through

In 2010, 87% of the world's Christian population lived in countries where Christians are in the majority, while 13% of the world's Christian population lived in countries where Christians are in the minority.[1] Christianity is the predominant religion in Europe, the Americas, Oceania, and Sub-Saharan Africa.[1] There are also large Christian communities in other parts of the world, such as Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.[1] In Asia, it is the dominant religion in Armenia, Cyprus, Georgia, East Timor, and the Philippines.[299] However, it is declining in some areas including the northern and western United States,[300] some areas in Oceania (Australia[301] and New Zealand[302]), northern Europe (including Great Britain,[303] Scandinavia and other places), France, Germany, Canada,[304] and some parts of Asia (especially the Middle East, due to the Christian emigration,[305][306][307] and Macau[308]).

The total Christian population is not decreasing in Brazil and the southern United States,

Despite a decline in adherence in the West, Christianity remains the dominant religion in the region, with about 70% of that population identifying as Christian.[1][315] Christianity remains the largest religion in Western Europe, where 71% of Western Europeans identified themselves as Christian in 2018.[316] A 2011 Pew Research Center survey found that 76% of Europeans, 73% in Oceania and about 86% in the Americas (90% in Latin America and 77% in North America) identified themselves as Christians.[282][1] By 2010 about 157 countries and territories in the world had Christian majorities.[282]

There are many

In most countries in the developed world, church attendance among people who continue to identify themselves as Christians has been falling over the last few decades.[335] Some sources view this as part of a drift away from traditional membership institutions,[336] while others link it to signs of a decline in belief in the importance of religion in general.[337] Europe's Christian population, though in decline, still constitutes the largest geographical component of the religion.[338] According to data from the 2012 European Social Survey, around a third of European Christians say they attend services once a month or more.[339] Conversely, according to the World Values Survey, about more than two-thirds of Latin American Christians, and about 90% of African Christians (in Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa and Zimbabwe) said they attended church regularly.[339] According to a 2018 study by the Pew Research Center, Christians in Africa and Latin America and the United States have high levels of commitment to their faith.[340]

There are numerous other countries, such as Cyprus, which although do not have an

| Tradition | Followers | % of the Christian population | % of the world population | Follower dynamics | Dynamics in- and outside Christianity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roman Catholic Church | 1,329,610,000 | 50.1 | 15.9 | ||

| Protestantism | 900,640,000 | 36.7 | 11.6 | ||

| Eastern Orthodox Church | 220,380,000 | 11.9 | 3.8 | ||

| Other Christianity | 28,430,000 | 1.3 | 0.4 | ||

| Christianity | 2,382,750,000 | 100 | 31.7 |

| Region | Christians | % Christian |

|---|---|---|

| Europe | 558,260,000 | 75.2 |

| Latin America–Caribbean | 531,280,000 | 90.0 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 517,340,000 | 62.9 |

Asia Pacific

|

286,950,000 | 7.1 |

| North America | 266,630,000 | 77.4 |

| Middle East–North Africa | 12,710,000 | 3.7 |

| World | 2,173,180,000 | 31.5 |

| Christian median age in region (years) |

Regional median age (years) | |

|---|---|---|

| World | 30 | 29 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 19 | 18 |

| Latin America-Caribbean | 27 | 27 |

Asia-Pacific

|

28 | 29 |

| Middle East-North Africa | 29 | 24 |

| North America | 39 | 37 |

| Europe | 42 | 40 |

-

Countries with 50% or more Christians are colored purple; countries with 10% to 50% Christians are colored pink.

-

Nations with Christianity as their state religion are in blue.

-

Distribution of Catholics

-

Distribution of Protestants

-

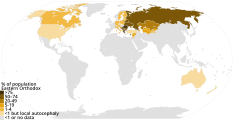

Distribution of Eastern Orthodox

-

Distribution of Oriental Orthodox

-

Distribution of other Christians

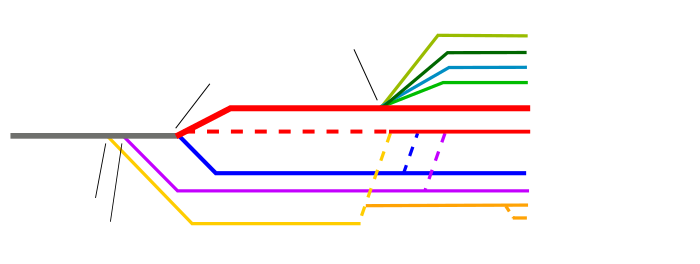

Churches and denominations

Christianity can be taxonomically divided into six main groups: Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, Oriental Orthodoxy, Eastern Orthodoxy, the Church of the East, and Restorationism.[355][356] A broader distinction that is sometimes drawn is between Eastern Christianity and Western Christianity, which has its origins in the East–West Schism (Great Schism) of the 11th century. Recently, neither Western nor Eastern World Christianity has also stood out, for example, in African-initiated churches. However, there are other present[357] and historical[358] Christian groups that do not fit neatly into one of these primary categories.

There is a diversity of doctrines and liturgical practices among groups calling themselves Christian. These groups may vary ecclesiologically in their views on a classification of Christian denominations.[359] The Nicene Creed (325), however, is typically accepted as authoritative by most Christians, including the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and major Protestant, such as Lutheran and Anglican denominations.[360]

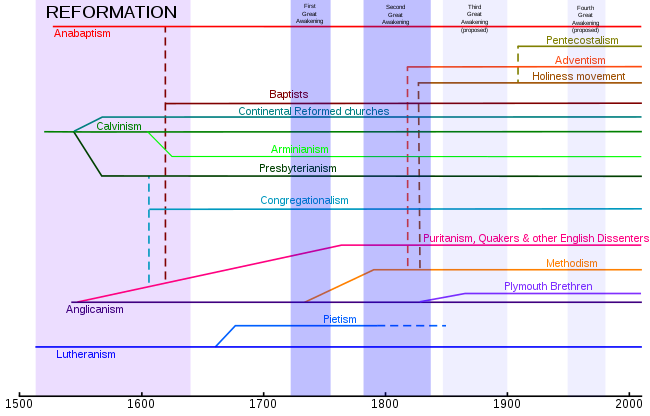

- (Not shown are ante-Nicene, nontrinitarian, and restorationist denominations.)

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church consists of those

Of its

As the world's oldest and largest continuously functioning international institution,[377] it has played a prominent role in the history and development of Western civilization.[378] The 2,834 sees[379] are grouped into 24 particular autonomous Churches (the largest of which being the Latin Church), each with its own distinct traditions regarding the liturgy and the administering of sacraments.[380] With more than 1.1 billion baptized members, the Catholic Church is the largest Christian church and represents 50.1%[1] of all Christians as well as 16.7% of the world's population.[381][382][383] Catholics live all over the world through missions, diaspora, and conversions.

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church consists of those churches in communion with the patriarchal sees of the East, such as the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople.[385] Like the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church also traces its heritage to the foundation of Christianity through apostolic succession and has an episcopal structure, though the autonomy of its component parts is emphasized, and most of them are national churches.

Eastern Orthodoxy is the second largest single denomination in Christianity, with an estimated 230 million adherents, although

Oriental Orthodoxy

The

The Oriental Orthodox communion consists of six groups:

As some of the oldest religious institutions in the world, the Oriental Orthodox Churches have played a prominent role in the history and culture of

Some Oriental Orthodox Churches such as the

Church of the East

The

The

Its main spoken language is

The Ancient Church of the East distinguished itself from the Assyrian Church of the East in 1964. It is one of the Assyrian churches that claim continuity with the historical Church of the East, one of the oldest Christian churches in Mesopotamia.[411] It is officially headquartered in the city of Baghdad, Iraq.[412] The majority of its adherents are ethnic Assyrians.[412]

Protestantism

In 1521, the

Since the Anglican, Lutheran, and the Reformed branches of Protestantism originated for the most part in cooperation with the government, these movements are termed the "

The term Protestant also refers to any churches which formed later, with either the Magisterial or Radical traditions. In the 18th century, for example,

Protestantism is the second largest major group of Christians after Catholicism by number of followers, although the Eastern Orthodox Church is larger than any single Protestant denomination.

Some groups of individuals who hold basic Protestant tenets identify themselves as "Christians" or "

Restorationism

The

Some of the churches originating during this period are historically connected to early 19th-century camp meetings in the Midwest and upstate New York. One of the largest churches produced from the movement is

Other

Within Italy, Poland, Lithuania, Transylvania, Hungary, Romania, and the United Kingdom,

Various smaller

Messianic Judaism (or the Messianic Movement) is the name of a Christian movement comprising a number of streams, whose members may consider themselves Jewish. The movement originated in the 1960s and 1970s, and it blends elements of religious Jewish practice with evangelical Christianity. Messianic Judaism affirms Christian creeds such as the messiahship and divinity of "Yeshua" (the Hebrew name of Jesus) and the Triune Nature of God, while also adhering to some Jewish dietary laws and customs.[449]

Cultural influence

The history of the

The Bible has had a profound influence on Western civilization and on cultures around the globe; it has contributed to the formation of

Outside the Western world, Christianity has had an influence on various cultures, such as in Africa, the Near East, Middle East, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.

Influence on Western culture

Though Western culture contained several polytheistic religions during its early years under the Greek and Roman Empires, as the centralized Roman power waned, the dominance of the Catholic Church was the only consistent force in Western Europe.[493] Until the Age of Enlightenment,[493] Christian culture guided the course of philosophy, literature, art, music and science.[493][462] Christian disciplines of the respective arts have subsequently developed into Christian philosophy, Christian art, Christian music, Christian literature, and so on.

Christianity has had a significant impact on education, as the church created the bases of the Western system of education,

Ecumenism

Christian groups and

The other way was an institutional union with united churches, a practice that can be traced back to unions between Lutherans and Calvinists in early 19th-century Germany. Congregationalist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches united in 1925 to form the United Church of Canada,[519] and in 1977 to form the Uniting Church in Australia. The Church of South India was formed in 1947 by the union of Anglican, Baptist, Methodist, Congregationalist, and Presbyterian churches.[520]

The Christian Flag is an ecumenical flag designed in the early 20th century to represent all of Christianity and Christendom.[521]

The ecumenical, monastic Taizé Community is notable for being composed of more than one hundred brothers from Protestant and Catholic traditions.[522] The community emphasizes the reconciliation of all denominations and its main church, located in Taizé, Saône-et-Loire, France, is named the "Church of Reconciliation".[522] The community is internationally known, attracting over 100,000 young pilgrims annually.[523]

Steps towards reconciliation on a global level were taken in 1965 by the Catholic and Orthodox churches, mutually revoking the excommunications that marked their

Criticism, persecution, and apologetics

Criticism

Criticism of Christianity and Christians goes back to the

By the 3rd century, criticism of Christianity had mounted. Wild rumors about Christians were widely circulated, claiming that they were atheists and that, as part of their rituals, they devoured human infants and engaged in incestuous orgies.[535][536] The Neoplatonist philosopher Porphyry wrote the fifteen-volume Adversus Christianos as a comprehensive attack on Christianity, in part building on the teachings of Plotinus.[537][538]

By the 12th century, the

Criticism of Christianity continues to date, e.g.

Persecution

Christians are one of the most

Apologetics

Christian apologetics aims to present a

See also

- Outline of Christianity

- Christian atheism

- Christianity and Islam

- Christianity and Judaism

- Christianity and politics

- Christian mythology

- Christianisation

- One true church

- Prophets of Christianity

- Jamieson-Fausset-Brown Bible Commentary

Notes

- Congregationalists, Continental Reformed, and Presbyterians), and Waldensianism are the main families of Protestantism. Other groups that are sometimes regarded as Protestant include non-denominational Christian congregations.[12]

- ^ The denominations of Restorationism include the Irvingians, Swedenborgians, Christadelphians, Latter Day Saints, Jehovah's Witnesses, La Luz del Mundo, and Iglesia ni Cristo.[15][16]

- English translations of the New Testament capitalize 'the Way' (e.g. the New King James Version and the English Standard Version), indicating that this was how 'the new religion seemed then to be designated'[17] whereas others treat the phrase as indicative—'the way',[18] 'that way'[19] or 'the way of the Lord'.[20] The Syriac version reads, "the way of God" and the Vulgate Latin version, "the way of the Lord".[21]

- ^

- ^ Frequently a distinction is made between "liturgical" and "non-liturgical" churches based on how elaborate or antiquated the worship; in this usage, churches whose services are unscripted or improvised are described as "non-liturgical".[103]

- ^ Often these are arranged on an annual cycle, using a book called a lectionary.

- majusculescript of the time.

- ^ A flexible term, defined as all forms of Protestantism with the notable exception of the historical denominations deriving directly from the Protestant Reformation.

- Stone-Campbell Restoration Movement are tied to associations such as the Churches of Christ or the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).[457][458]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Global Christianity – A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population" (PDF). Pew Research Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 August 2019.

- S2CID 152458823. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-8028-2861-3. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- S2CID 170124789. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- S2CID 160590164. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- S2CID 191738355. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ]

- ^ a b "World's largest religion by population is still Christianity". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-111-83720-4.

- ^ Bokenkotter 2004, Preface.

- ISBN 978-0-7581-3510-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8160-6983-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-8309-8876-2.

- ISBN 978-0-429-61992-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4982-3145-9.

The Second Great Awakening (1790-1840) spurred a renewed interest in primitive Christianity. What is known as the Restoration Movement of the nineteenth century gave birth to an array of groups: Mormons (The Latter Day Saint Movement), the Churches of Christ, Adventists, and Jehovah's Witnesses. Though these groups demonstrate a breathtaking diversity on the continuum of Christianity they share an intense restorationist impulse. Picasso and Stravinsky reflect a primitivism that came to the fore around the turn of the twentieth century that more broadly has been characterized as a "retreat from the industrialized world."

- ^ ISBN 978-1-351-90583-1.

However, Swedenborg claimed to receive visions and revelations of heavenly things and a 'New Church', and the new church which was founded upon his writings was a Restorationist Church. The three nineteenth-century churches are all examples of Restorationist Churches, which believed they were refounding the Apostolic Church, and preparing for the Second Coming of Christ.

- ^ "Acts 19 | Jamieson-Fausset-Brown Bible Commentary". biblehub.com. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Jubilee Bible 2000

- American King James Version

- Douai-Rheims Bible

- ^ "Online Bible Study Suite | Gill, J., Gill's Exposition of the Bible, commentary on Acts 19:23". Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ E. Peterson (1959), "Christianus." In: Frühkirche, Judentum und Gnosis, publisher: Herder, Freiburg, pp. 353–72

- ^ Elwell & Comfort 2001, pp. 266, 828.

- ^ Olson, The Mosaic of Christian Belief.

- ISBN 978-1-55673-979-8.

- ^ Pelikan/Hotchkiss, Creeds and Confessions of Faith in the Christian Tradition.

- ^ ""We Believe in One God....": The Nicene Creed and Mass". Catholics United for the Fath. February 2005. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Religion, "Arianism".

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, "Council of Ephesus".

- ^ Christian History Institute, First Meeting of the Council of Chalcedon.

- ^ Peter Theodore Farrington (February 2006). "The Oriental Orthodox Rejection of Chalcedon". Glastonbury Review (113). Archived from the original on 19 June 2008.

- ^ Pope Leo I, Letter to Flavian Archived 20 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, "Athanasian Creed".

- ^ a b "Our Common Heritage as Christians". The United Methodist Church. Archived from the original on 14 January 2006. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- ^ White, Howard A. The History of the Church Archived 30 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ISBN 978-0-8272-1425-5.

- ISBN 0736912894

- ^ Woodhead 2004, p. 45

- ^ Woodhead 2004, p. n.p

- ^ Metzger/Coogan, Oxford Companion to the Bible, pp. 513, 649.

- ^ Acts 2:24, 2:31–32, 3:15, 3:26, 4:10, 5:30, 10:40–41, 13:30, 13:34, 13:37, 17:30–31, Romans 10:9, 1 Cor. 15:15, 6:14, 2 Cor. 4:14, Gal 1:1, Eph 1:20, Col 2:12, 1 Thess. 11:10, Heb. 13:20, 1 Pet. 1:3, 1:21

- ^ s:Nicene Creed

- ^ Acts 1:9–11

- ISBN 978-0-89870-686-4– via Google Books.

- ISBN 978-1-4185-1723-6.

- ^ "The Significance of the Death and Resurrection of Jesus for the Christian". Australian Catholic University National. Archived from the original on 1 September 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- ^ Jn. 19:30–31 Mk. 16:1 16:6

- ^ 1Cor 15:6

- ^ John 3:16, 5:24, 6:39–40, 6:47, 10:10, 11:25–26, and 17:3

- ^ This is drawn from a number of sources, especially the early Creeds, the Catechism of the Catholic Church, certain theological works, and various Confessions drafted during the Reformation including the Thirty Nine Articles of the Church of England, works contained in the Book of Concord.

- ^ Fuller, The Foundations of New Testament Christology, p. 11.

- ."

- ^ Funk. The Acts of Jesus: What Did Jesus Really Do?.

- ^ Lorenzen. Resurrection, Discipleship, Justice: Affirming the Resurrection Jesus Christ Today, p. 13.

- ^ 1Cor 15:14

- ^ Ball/Johnsson (ed.). The Essential Jesus.

- ^ "John 3:16 New International Version". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- ^ Gal. 3:29

- ^ Wright, N.T. What Saint Paul Really Said: Was Paul of Tarsus the Real Founder of Christianity? (Oxford, 1997), p. 121.

- ^ Rom. 8:9,11,16

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 846.

- L. W. Grensted, A Short History of the Doctrine of the Atonement (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1920), p. 191: 'Before the Reformation only a few hints of a Penal theory can be found.'

- ^ Westminster Confession, Chapter X Archived 28 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine;

Spurgeon, A Defense of Calvinism Archived 10 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine. - ^ "Grace and Justification". Catechism of the Catholic Church. Archived from the original on 15 August 2010.

- Fourth Lateran Council quoted in Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 253..

- Cultural Literacy, monotheism; New Dictionary of Theology, Paul Archived 20 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 496–499; Meconi. "Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity". pp. 111ff.

- ^ Kelly. Early Christian Doctrines. pp. 87–90.

- ^ Alexander. New Dictionary of Biblical Theology. pp. 514ff.

- ^ McGrath. Historical Theology. p. 61.

- ^ Metzger/Coogan. Oxford Companion to the Bible. p. 782.

- ^ Kelly. The Athanasian Creed.

- ISBN 978-0-19-522393-4.

- ISBN 0865548501, pp. 32–35.

- ^ Examples of ante-Nicene statements:

Hence all the power of magic became dissolved; and every bond of wickedness was destroyed, men's ignorance was taken away, and the old kingdom abolished God Himself appearing in the form of a man, for the renewal of eternal life.

— St. Ignatius of Antioch in Letter to the Ephesians, ch.4, shorter version, Roberts-Donaldson translationWe have also as a Physician the Lord our God Jesus the Christ the only-begotten Son and Word, before time began, but who afterwards became also man, of Mary the virgin. For 'the Word was made flesh.' Being incorporeal, He was in the body; being impassible, He was in a passable body; being immortal, He was in a mortal body; being life, He became subject to corruption, that He might free our souls from death and corruption, and heal them, and might restore them to health, when they were diseased with ungodliness and wicked lusts

— St. Ignatius of Antioch in Letter to the Ephesians, ch.7, shorter version, Roberts-Donaldson translationThe Church, though dispersed throughout the whole world, even to the ends of the earth, has received from the apostles and their disciples this faith: ...one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven, and earth, and the sea, and all things that are in them; and in one Christ Jesus, the Son of God, who became incarnate for our salvation; and in the Holy Spirit, who proclaimed through the prophets the dispensations of God, and the advents, and the birth from a virgin, and the passion, and the resurrection from the dead, and the ascension into heaven in the flesh of the beloved Christ Jesus, our Lord, and His manifestation from heaven in the glory of the Father 'to gather all things in one,' and to raise up anew all flesh of the whole human race, in order that to Christ Jesus, our Lord, and God, and Savior, and King, according to the will of the invisible Father, 'every knee should bow, of things in heaven, and things in earth, and things under the earth, and that every tongue should confess; to him, and that He should execute just judgment towards all...

— St. Irenaeus in Against Heresies, ch.X, v.I, Donaldson, Sir James (1950), Ante Nicene Fathers, Volume 1: Apostolic Fathers, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus,ISBN 978-0-8028-8087-1For, in the name of God, the Father and Lord of the universe, and of our Savior Jesus Christ, and of the Holy Spirit, they then receive the washing with water

— Justin Martyr in First Apology, ch. LXI, Donaldson, Sir James (1950), Ante Nicene Fathers, Volume 1: Apostolic Fathers, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company,ISBN 978-0-8028-8087-1 - ISBN 978-0-8028-4827-7.

- ^ Fowler. World Religions: An Introduction for Students. p. 58.

- Perseus Project.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "trinity". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Perseus Project.

- Perseus Project.

- Patrologiae GraecaeCursus Completus (in Greek and Latin). Vol. 6.

Ὡσαύτως καὶ αἱ τρεῖς ἡμέραι τῶν φωστήρων γεγονυῖαι τύποι εἰσὶν τῆς Τριάδος, τοῦ Θεοῦ, καὶ τοῦ Λόγου αὐτοῦ, καὶ τῆς Σοφίας αὐτοῦ.

- ^ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. p. 50.

- ^ Tertullian, "21", De Pudicitia (in Latin),

Nam et ipsa ecclesia proprie et principaliter ipse est spiritus, in quo est trinitas unius diuinitatis, Pater et Filius et Spiritus sanctus.

. - ^ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity, p. 53.

- ISBN 080062825X

- ^ Harnack, History of Dogma.

- ^ Pocket Dictionary of Church History Nathan P. Feldmeth p. 135 "Unitarianism. Unitarians emerged from Protestant Christian beginnings in the sixteenth century with a central focus on the unity of God and subsequent denial of the doctrine of the Trinity"

- ^ Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologicum, Supplementum Tertiae Partis questions 69 through 99

- ^ Calvin, John. "Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book Three, Ch. 25". reformed.org. Archived from the original on 10 December 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2008.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, "Particular Judgment".

- ^ Ott, Grundriß der Dogmatik, p. 566.

- ^ David Moser, What the Orthodox believe concerning prayer for the dead.

- ^ Ken Collins, What Happens to Me When I Die? Archived 28 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Audience of 4 August 1999". Vatican.va. 4 August 1999. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, "The Communion of Saints".

- ^ "The death that Adam brought into the world is spiritual as well as physical, and only those who gain entrance into the Kingdom of God will exist eternally. However, this division will not occur until Armageddon, when all people will be resurrected and given a chance to gain eternal life. In the meantime, "the dead are conscious of nothing." What is God's Purpose for the Earth?" Official Site of Jehovah's Witnesses. Watchtower, 15 July 2002.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-62189-635-7.

- ^ a b White 2010, pp. 71–82

- ISBN 978-0-7914-4062-9.

- ISBN 978-0-8070-6750-5.

the ancient church had three important languages: Greek, Latin, and Syriac.

- ISBN 978-0-8070-6750-5.

the ancient church had three important languages: Greek, Latin, and Syriac.

- ISBN 978-1-59942-877-2.

- ^ a b Justin Martyr, First Apology §LXVII

- ^ White 2010, p. 36

- ISBN 978-0-8028-0767-0. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ Wallwork, Norman (2019). "The Purpose of a Hymn Book" (PDF). Joint Liturgical Group of Great Britain. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ For example, The Calendar, Church of England, retrieved 25 June 2020

- ^ Ignazio Silone, Bread and Wine (1937).

- ISBN 978-0-202-36575-6.

- Archive.org

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1415.

- ^ "An open table: How United Methodists understand communion – The United Methodist Church". United Methodist Church. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "Order of Worship". Wilmore Free Methodist Church. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ "Canon B28 of the Church of England".

- ^ a b c Cross/Livingstone. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. pp. 1435ff.

- ^ Krahn, Cornelius; Rempel, John D. (1989). Ordinances. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia.

The term "ordinance" emphasizes the aspect of institution by Christ and the symbolic meaning.

- ^ Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East, Archdiocese of Australia, New Zealand and Lebanon.

- ^ "Love Feast of the Dunkards; Peculiar Ceremonies of a Peculiar Sect of Christians". The New York Times. 26 April 1891. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-4514-2433-1.

For example, days of Mary, Joseph, and John the Baptist (e.g., August 15, March 19, June 24, respectively) are ranked as solemnities in the Roman Catholic calendar; in the Anglican and Lutheran calendars they are holy days or lesser festivals respectively.

- ^ a b Fortescue, Adrian (1912). "Christian Calendar". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Hickman. Handbook of the Christian Year.

- JSTOR 1291064.

- ISBN 0-7044-0226-2.

- ^ "ANF04. Fathers of the Third Century: Tertullian, Part Fourth; Minucius Felix; Commodian; Origen, Parts First and Second | Christian Classics Ethereal Library". Ccel.org. 1 June 2005. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Minucius Felix speaks of the cross of Jesus in its familiar form, likening it to objects with a crossbeam or to a man with arms outstretched in prayer (Octavius of Minucius Felix, chapter XXIX).

- ^ "At every forward step and movement, at every going in and out, when we put on our clothes and shoes, when we bathe, when we sit at table, when we light the lamps, on couch, on seat, in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we trace upon the forehead the sign." (Tertullian, De Corona, chapter 3)

- ^ a b Dilasser. The Symbols of the Church.

- ^ a b Hassett, Maurice M. (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1213.

Through Baptism we are freed from sin and reborn as sons of God; we become members of Christ, are incorporated into the Church and made sharers in her mission.

- ^ "Holy Baptism is the sacrament by which God adopts us as his children and makes us members of Christ's Body, the Church, and inheritors of the kingdom of God" (Book of Common Prayer, 1979, Episcopal) Archived 19 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Baptism is the sacrament of initiation and incorporation into the body of Christ" (By Water and The Spirit – The Official United Methodist Understanding of Baptism (PDF) Archived 13 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "As an initiatory rite into membership of the Family of God, baptismal candidates are symbolically purified or washed as their sins have been forgiven and washed away" (William H. Brackney, Doing Baptism Baptist Style – Believer's Baptism Archived 7 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "After the proclamation of faith, the baptismal water is prayed over and blessed as the sign of the goodness of God's creation. The person to be baptized is also prayed over and blessed with sanctified oil as the sign that his creation by God is holy and good. And then, after the solemn proclamation of "Alleluia" (God be praised), the person is immersed three times in the water in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit" (Orthodox Church in America: Baptism). Archived 12 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "In the Orthodox Church we totally immerse, because such total immersion symbolizes death. What death? The death of the "old, sinful man". After Baptism we are freed from the dominion of sin, even though after Baptism we retain an inclination and tendency toward evil.", Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia, article "Baptism Archived 30 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine".

- ^ Olson, Karen Bates (12 January 2017). "Why infant baptism?". Living Lutheran. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 403.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraphs 1231, 1233, 1250, 1252.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1240.

- ^ Eby, Edwin R. "Early Anabaptist Positions on Believer's Baptism and a Challenge for Today". Pilgrim Mennonite Conference. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

They concluded according to the Scriptures that baptism must always follow a conscious decision to take up "following Christ." They believed that a regenerated life becomes the experience of an adult who counts the cost of following Christ, exercises obedience to Christ, and is therefore baptized as a sign of such commitment and life.

- ISBN 978-1-4934-0640-1.

The Conservative Mennonite Conference practices believer's baptism, seen as an external symbol of internal spiritual purity and performed by immersion or pouring of water on the head; Communion; washing the feet of the saints, following Jesus's example and reminding believers of the need to be washed of pride, rivalry, and selfish motives; anointing the sick with oil – a symbol of the Holy Spirit and of the healing power of God—offered with the prayer of faith; and laying on of hands for ordination, symbolizing the imparting of responsibility and of God's power to fulfill that responsibility.

- ISBN 978-0-8018-9911-9.

All Amish, Hutterites, and most Mennonites baptized by pouring or sprinkling.

- ISBN 978-0-8316-9701-3.

...both groups practiced believers baptism (the River Brethren did so by immersion in a stream or river) and stressed simplicity in life and nonresistance to violence.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-7365-0.

The birthdate in 1708 marked the baptism by immersion of the group in the River Eder, thus believer's baptism became one of the primary tenets of The Brethren.

- ^ "Matthew 6:9–13 Evangelical Heritage Version (EHV)". Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-7487-5320-8.

When he was standing on a hillside, Jesus explained to his followers how they were to behave as God would wish. The talk has become known as the Sermon on the Mount, and is found in the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 5, 6 and 7. During the talk Jesus taught his followers how to pray and he gave them an example of suitable prayer. Christians call the prayer the Lord's Prayer, because it was taught by the Lord, Jesus Christ. It is also known as the Pattern Prayer as it provides a pattern for Christians to follow in prayer, to ensure that they pray in the way God and Jesus would want.

- ISBN 978-0-8091-0537-3.

Given the placement of the Lord's Prayer in the Didache, it was to be expected that the new member of the community would come to learn and to pray the Lord's Prayer at the appointed hours three times each day only after baptism (8:2f.).

- ISBN 978-90-04-14603-7.

So three minor hours of prayer were developed, at the third, sixth and ninth hours, which, as Dugmore points out, were ordinary divisions of the day for worldly affairs, and the Lord's Prayer was transferred to those hours.

- ISBN 978-1-101-16042-8.

Hippolytus in the Apostolic Tradition directed that Christians should pray seven times a day – on rising, at the lighting of the evening lamp, at bedtime, at midnight, and also, if at home, at the third, sixth and ninth hours of the day, being hours associated with Christ's Passion. Prayers at the third, sixth, and ninth hours are similarly mentioned by Tertullian, Cyprian, Clement of Alexandria and Origen, and must have been very widely practised. These prayers were commonly associated with private Bible reading in the family.

- ISBN 978-0-567-16561-9.

Not only the content of early Christian prayer was rooted in Jewish tradition; its daily structure too initially followed a Jewish pattern, with prayer times in the early morning, at noon and in the evening. Later (in the course of the second century), this pattern combined with another one; namely prayer times in the evening, at midnight and in the morning. As a result seven 'hours of prayer' emerged, which later became the monastic 'hours' and are still treated as 'standard' prayer times in many churches today. They are roughly equivalent to midnight, 6 a.m., 9 a.m., noon, 3 p.m., 6 p.m. and 9 p.m. Prayer positions included prostration, kneeling and standing. ... Crosses made of wood or stone, or painted on walls or laid out as mosaics, were also in use, at first not directly as objections of veneration but in order to 'orientate' the direction of prayer (i.e. towards the east, Latin oriens).

- ^ Kurian, Jake. ""Seven Times a Day I Praise You" – The Shehimo Prayers". Diocese of South-West America of the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Mary Cecil, 2nd Baroness Amherst of Hackney (1906). A Sketch of Egyptian History from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Methuen. p. 399.

Prayers 7 times a day are enjoined, and the most strict among the Copts recite one of more of the Psalms of David each time they pray. They always wash their hands and faces before devotions, and turn to the East.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Hippolytus. "Apostolic Tradition" (PDF). St. John's Episcopal Church. pp. 8, 16, 17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Acts 9:40

- ^ 1Kings 17:19–22

- ^ James 5:16–18

- ^ Alexander, T.D.; Rosner, B.S, eds. (2001). "Prayer". New Dictionary of Biblical Theology. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press.

- Evangelical Community Church-Lutheran. Archived from the originalon 18 May 2007. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ Ferguson, S.B. & Packer, J. (1988). "Saints". New Dictionary of Theology. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press.

- ^ Madeleine Gray, The Protestant Reformation, (Sussex Academic Press, 2003), p. 140.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 2559.

- ^ "The Book of Common Prayer". Church of England. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-8010-3138-0.

- ^ "Inspiration and Truth of Sacred Scripture". Catechism of the Catholic Church. Archived from the original on 9 September 2010.(§ 105–108)

- ^ Second Helvetic Confession, Of the Holy Scripture Being the True Word of God

- ^ Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, online text Archived 29 January 1998 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 978-0-88141-301-4.

- ^ Metzger/Coogan, Oxford Companion to the Bible. p. 39.

- ^ John Bowker, 2011, The Message and the Book, UK, Atlantic Books, pp. 13–14

- ^ Kelly. Early Christian Doctrines. pp. 69–78.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, The Holy Spirit, Interpreter of Scripture § 115–118. Archived 25 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 1Cor 10:2

- ^ Thomas Aquinas, "Whether in Holy Scripture a word may have several senses" Archived 6 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, § 116 Archived 25 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Second Vatican Council, Dei Verbum (V.19) Archived 31 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, "The Holy Spirit, Interpreter of Scripture" § 113. Archived 25 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, "The Interpretation of the Heritage of Faith" § 85. Archived 3 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Methodist Beliefs: In what ways are Lutherans different from United Methodists?". Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod. 2014. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

The United Methodists see Scripture as the primary source and criterion for Christian doctrine. They emphasize the importance of tradition, experience, and reason for Christian doctrine. Lutherans teach that the Bible is the sole source for Christian doctrine. The truths of Scripture do not need to be authenticated by tradition, human experience, or reason. Scripture is self authenticating and is true in and of itself.

- ISBN 978-1-885767-74-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4412-4048-4.

historically Anglicans have adopted what could be called a prima Scriptura position.

- ^ a b Foutz, Scott David. "Martin Luther and Scripture". Quodlibet Journal. Archived from the original on 14 April 2000. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ John Calvin, Commentaries on the Catholic Epistles 2 Peter 3:14–18

- ^ Engelder, Theodore E.W. (1934). Popular Symbolics: The Doctrines of the Churches of Christendom and of Other Religious Bodies Examined in the Light of Scripture. Saint Louis, MO: Concordia Publishing House. p. 28.

- ^ Sproul. Knowing Scripture, pp. 45–61; Bahnsen, A Reformed Confession Regarding Hermeneutics (article 6) Archived 4 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8010-3413-8.

- ISBN 978-0-310-34160-4.

- ^ Terry, Milton (1974). Biblical hermeneutics : a treatise on the interpretation of the Old and New Testaments. Grand Rapids Mich.: Zondervan Pub. House. p. 205. (1890 edition page 103, view1, view2)

- Jewish Christians. For a contemporary treatment, see Glenny, Typology: A Summary Of The Present Evangelical Discussion.

- . Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ISBN 978-1-317-34958-7.

- ISBN 978-0-253-34286-7.

- ISBN 1-4051-0899-1

- ISSN 0167-9732.

- ISBN 0195118758, p. 426.

- ^ Acts 7:59

- ^ Acts 12:2

- ^ Martin, D. 2010. The "Afterlife" of the New Testament and Postmodern Interpretation Archived 8 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine (lecture transcript Archived 12 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine). Yale University.

- ^ "Monastère de Mor Mattai – Mossul – Irak" (in French). Archived from the original on 3 March 2014.

- ^ Michael Whitby, et al. eds. Christian Persecution, Martyrdom and Orthodoxy (2006) online edition Archived 24 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Eusebius of Caesarea, the author of Ecclesiastical Historyin the 4th century, states that St. Mark came to Egypt in the first or third year of the reign of Emperor Claudius, i.e. 41 or 43 AD. "Two Thousand years of Coptic Christianity" Otto F.A. Meinardus p. 28.

- ^ Lettinga, Neil. "A History of the Christian Church in Western North Africa". Archived from the original on 30 July 2001.

- ^ "Allaboutreligion.org". Allaboutreligion.org. Archived from the original on 16 November 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ a b "Armenia". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 8 October 2011. (Archived 2011 edition.)

- ^ ISBN 978-1-933405-49-0.

- ^ Theo Maarten van Lint (2009). "The Formation of Armenian Identity in the First Millennium". Church History and Religious Culture. 89 (1/3): 269.

- ISBN 978-1-4742-5467-0.

- ^ Chidester, David (2000). Christianity: A Global History. HarperOne. p. 91.

- ^ Ricciotti 1999

- ^ Theodosian Code XVI.i.2 Archived 14 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine, in: Bettenson. Documents of the Christian Church. p. 31.

- ^ Burbank, Jane; Copper, Frederick (2010). Empires in World History: Power and the Politics of Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 64.

- ISBN 978-1-4185-5281-7.

The Nicene Creed, as used in the churches of the West (Anglican, Catholic, Lutheran, and others), contains the statement, "We believe [or I believe] in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son."

- ^ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity, pp. 37ff.

- ^ a b Cameron 2006, p. 42.

- ^ Cameron 2006, p. 47.

- ^ Browning 1992, pp. 198–208.

- ^ Browning 1992, p. 218.

- ^ a b c d González 1984, pp. 238–242

- OCLC 910498369.

- ^ Mullin 2008, p. 88.

- ^ Mullin 2008, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Religions in Global Society. p. 146, Peter Beyer, 2006

- ^ Cambridge University Historical Series, An Essay on Western Civilization in Its Economic Aspects, p. 40: Hebraism, like Hellenism, has been an all-important factor in the development of Western Civilization; Judaism, as the precursor of Christianity, has indirectly had had much to do with shaping the ideals and morality of western nations since the christian era.

- ^ Caltron J.H Hayas, Christianity and Western Civilization (1953), Stanford University Press, p. 2: "That certain distinctive features of our Western civilization—the civilization of western Europe and of America—have been shaped chiefly by Judaeo – Graeco – Christianity, Catholic and Protestant."

- ^ Fred Reinhard Dallmayr, Dialogue Among Civilizations: Some Exemplary Voices (2004), p. 22: Western civilization is also sometimes described as "Christian" or "Judaeo- Christian" civilization.

- ^ González 1984, pp. 244–47

- ^ González 1984, p. 260

- ^ González 1984, pp. 278–281

- ISBN 0872493768, pp. 126–127, 282–298

- ^ Rudy, The Universities of Europe, 1100–1914, p. 40

- ^ ISBN 978-2868473448. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Verger, Jacques. "The Universities and Scholasticism", in The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume V c. 1198–c. 1300. Cambridge University Press, 2007, 257.

- ISBN 0521361052, pp. xix–xx

- ^ González 1984, pp. 303–307, 310ff., 384–386

- ^ González 1984, pp. 305, 310ff., 316ff

- ^ González 1984, pp. 321–323, 365ff

- ^ Parole de l'Orient, Volume 30. Université Saint-Esprit. 2005. p. 488.

- ^ González 1984, pp. 292–300

- ^ Riley-Smith. The Oxford History of the Crusades.

- ^ "The Great Schism: The Estrangement of Eastern and Western Christendom". Orthodox Information Centre. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- ^ Duffy, Saints and Sinners (1997), p. 91

- ISBN 978-1-101-18999-3.

- ISBN 978-0-688-08506-3.

- ^ González 1984, pp. 300, 304–305

- ^ González 1984, pp. 310, 383, 385, 391

- ^ a b Simon. Great Ages of Man: The Reformation. pp. 39, 55–61.

- ^ Simon. Great Ages of Man: The Reformation. p. 7.

- ^ Schama. A History of Britain. pp. 306–310.

- ^ National Geographic, 254.

- ISBN 0395889472

- ^ Levey, Michael (1967). Early Renaissance. Penguin Books.

- ^ Bokenkotter 2004, pp. 242–244.

- ^ Simon. Great Ages of Man: The Reformation. pp. 109–120.

- ^ A general overview about the English discussion is given in Coffey, Persecution and Toleration in Protestant England 1558–1689.

- ^ a b Open University, Looking at the Renaissance: Religious Context in the Renaissance (Retrieved 10 May 2007)

- ^ Some scholars and historians attribute Christianity to having contributed to the rise of the Scientific Revolution:

- Harrison, Peter (8 May 2012). "Christianity and the rise of western science". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- Noll, Mark, Science, Religion, and A.D. White: Seeking Peace in the "Warfare Between Science and Theology" (PDF), The Biologos Foundation, p. 4, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2015, retrieved 14 January 2015

- ISBN 978-0-520-05538-4

- Gilley, Sheridan (2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 8, World Christianities c. 1815 – c. 1914. Brian Stanley. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 0-521-81456-1.

- Lindberg, David. (1992). The Beginnings of Western Science. University of Chicago Press. p. 204.

- Polski słownik biograficzny (Polish Biographical Dictionary), vol. XIV, Wrocław, Polish Academy of Sciences, 1969, p. 11.

- ISBN 0-521-56671-1.

- ^ "Because he would not accept the Formula of Concord without some reservations, he was excommunicated from the Lutheran communion. Because he remained faithful to his Lutheranism throughout his life, he experienced constant suspicion from Catholics." John L. Treloar, "Biography of Kepler shows man of rare integrity. Astronomer saw science and spirituality as one." National Catholic Reporter, 8 October 2004, p. 2a. A review of James A. Connor Kepler's Witch: An Astronomer's Discovery of Cosmic Order amid Religious War, Political Intrigue and Heresy Trial of His Mother, Harper San Francisco.

- ^ Richard S. Westfall – Indiana University The Galileo Project. (Rice University). Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- ^ "The Boyle Lecture". St. Marylebow Church. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-88738-763-0.

- ^ Mortimer Chambers, The Western Experience (vol. 2) chapter 21.

- ^ Religion and the State in Russia and China: Suppression, Survival, and Revival, by Christopher Marsh, p. 47. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011.

- ^ Inside Central Asia: A Political and Cultural History, by Dilip Hiro. Penguin, 2009.

- ISBN 978-8185574479.

Forced Conversion under Atheistic Regimes: It might be added that the most modern example of forced "conversions" came not from any theocratic state, but from a professedly atheist government—that of the Soviet Union under the Communists.

- ^ Geoffrey Blainey 2011). A Short History of Christianity; Viking; p. 494

- ISBN 978-3-17-019977-4.

- ISBN 978-0-19-820597-5.

- ^ The Oxford Handbook of Modern German History Helmut Walser Smith, p. 360, OUP Oxford, 2011

- ^ "Religion may become extinct in nine nations, study says". BBC News. 22 March 2011.

- ^ "図録▽世界各国の宗教". .ttcn.ne.jp. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- LCCN 2010046058.

- ^ Kim, Sebastian; Kim, Kirsteen (2008). Christianity as a World Religion. London: Continuum. p. 2.

- ISBN 978-1-60833-103-1.

- ISBN 978-0-19-829388-0.

- ^ a b "Religion Information Data Explorer | GRF". www.globalreligiousfutures.org. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Jan Pelikan, Jaroslav (13 August 2022). "Christianity". Encyclopædia Britannica.

It has become the largest of the world's religions and, geographically, the most widely diffused of all faiths.

- ^ Johnson, Todd M.; Grim, Brian J., eds. (2020). "All Religions (global totals)". World Religion Database. Leiden, Boston: BRILL, Boston University.

- ^ 31.4% of ≈7.4 billion world population (under the section 'People') "World". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. 14 December 2021. (Archived 2021 edition.)

- ^ "World's largest religion by population is still Christianity". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Todd M.; Grim, Brian J., eds. (2020). "All Religions (global totals)". World Religion Database. Leiden, Boston: BRILL, Boston University.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Analysis (19 December 2011). "Global religious landscape: Christians" (PDF). Pewforum.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-19-532092-3.

- ISBN 978-1-4744-1204-9.

- ^ Werner Ustorf. "A missiological postscript", in McLeod and Ustorf (eds), The Decline of Christendom in (Western) Europe, 1750–2000, (Cambridge University Press, 2003) pp. 219–20.

- ^ a b "The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010–2050" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 10 May 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-19-533852-2.

- ISBN 978-0-19-980834-2.

- ^ a b c "Pewforum: Christianity (2010)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 August 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-8308-5695-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hillerbrand, Hans J., "Encyclopedia of Protestantism: 4-volume Set", p. 1815, "Observers carefully comparing all these figures in the total context will have observed the even more startling finding that for the first time ever in the history of Protestantism, Wider Protestants will by 2050 have become almost exactly as numerous as Catholics – each with just over 1.5 billion followers, or 17 percent of the world, with Protestants growing considerably faster than Catholics each year."

- ^ Some scholars suggest that Pentecostalism is the fastest growing religion in the world:

- Miller, Donald E; Sargeant, Kimon H; Flory, Richard, eds. (2013). Spirit and Power: The Growth and Global Impact of Pentecostalism. Oxford University Press Scholarship. ISBN 978-0-19-934563-2.

Pentecostalism is the fastest-growing religious movement in the world

- Anderson, Allan; Bergunder, Michael; Droogers, Andre (2010). Studying Global PentecostalismTheories and Methods. University of California Press Scholarship. ISBN 978-0-520-26661-2.

With its remarkable ability to adapt to different cultures, Pentecostalism has become the world's fastest growing religious movement.

- "Pentecostalism—the fastest growing religion on earth". ABC. 30 May 2021.

- "Pentecostalism: Massive Global Growth Under the Radar". Pulitzer Center. 9 March 2015.

Today, one quarter of the two billion Christians in the world are Pentecostal or Charismatic. Pentecostalism is the fastest growing religion in the world.

- "Max Weber and Pentecostals in Latin America: The Protestant Ethic, Social Capital and Spiritual Capital Ethic, Social Capital and Spiritual Capital". Georgia State University. 9 May 2016.

Many scholars claim that Pentecostalism is the fastest growing religious phenomenon in human history.

- Miller, Donald E; Sargeant, Kimon H; Flory, Richard, eds. (2013). Spirit and Power: The Growth and Global Impact of Pentecostalism. Oxford University Press Scholarship.

- ISBN 978-0-19-804069-9.

- ^ Barker, Isabelle V. (2005). "Engendering Charismatic Economies: Pentecostalism, Global Political Economy, and the Crisis of Social Reproduction". American Political Science Association. pp. 2, 8 and footnote 14 on page 8. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ Todd M. Johnson, Gina A Zurlo, Albert W. Hickman, and Peter F. Grossing, "Christianity 2016: Latin America and Projecting Religions to 2050", International Bulletin of Mission Research, 2016, Vol. 40 (1) 22–29.

- ^ Barrett, 29.

- ^ Ross Douthat, "Fear of a Black Continent", The New York Times, 21 October 2018, 9.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica table of religions, by region. Retrieved November 2007. Archived 18 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ARIS 2008 Report: Part IA – Belonging. "American Religious Identification Survey 2008". B27.cc.trincoll.edu. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Australian 2006 census – Religion". Censusdata.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 19 November 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Table 28, 2006 Census Data – QuickStats About Culture and Identity – Tables. Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "New UK opinion poll shows continuing collapse of 'Christendom'". Ekklesia.co.uk. 23 December 2006. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "The Canadian census: A rich portrait of the country's religious and ethnocultural diversity". Statistics Canada. Government of Canada. 26 October 2022. Archived from the original on 17 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ^ Barrett/Kurian.World Christian Encyclopedia, p. 139 (Britain), 281 (France), 299 (Germany).

- ^ "Christians in the Middle East". BBC News. 15 December 2005. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Katz, Gregory (25 December 2006). "Is Christianity dying in the birthplace of Jesus?". Chron.com. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Greenlees, Donald (26 December 2007). "A Gambling-Fueled Boom Adds to a Church's Bane". The New York Times. Macao. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ Kosmin, Barry A.; Keysar, Ariela (2009). "American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS) 2008" (PDF). Hartford, CN: Trinity College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2009. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- ^ a b "Eastern and Western Europeans Differ on Importance of Religion, Views of Minorities, and Key Social Issues". Pew Research Center. 29 October 2018.

- JSTOR 3711910.

- ^ a b c "Understanding the rapid rise of Charismatic Christianity in Southeast Asia". Singapore Management University. 27 October 2017.

- ^ a b c The Next Christendom: The Rise of Global Christianity. New York: Oxford University Press. 2002. 270 pp.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Johnstone, Patrick; Miller, Duane Alexander (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR. 11 (10): 1–19. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-472-13174-7.

- ^ "Being Christian in Western Europe". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 29 May 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ David Stoll, "Is Latin America Turning Protestant?" published Berkeley: University of California Press. 1990

- ^ Hadden, Jeff (1997). "Pentecostalism". Archived from the original on 27 April 2006. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ^ Pew Forum on Religion; Public Life (24 April 2006). "Moved by the Spirit: Pentecostal Power and Politics after 100 Years". Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ^ "Pentecostalism". Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. 2007. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ Ed Gitre, Christianity Today Magazine (13 November 2000). "The CT Review: Pie-in-the-Sky Now".

- ISBN 978-0-8160-6983-5.

- ISBN 978-0-8308-2576-9.

- ISBN 978-1-74253-416-9.

Since the 1960s, there has been a substantial increase in the number of Muslims who have converted to Christianity

- ISBN 978-1-4982-8417-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Miller, Duane Alexander; Koepping, Elizabeth (2014). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". University of Edinburgh School of Divinity: 88–89.

- ISBN 978-1-4008-5125-6. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "Christian Converts in Morocco Fear Fatwa Calling for Their Execution". Morning Star News. 9 May 2013 – via Christianity Today.

- ^ "'House-Churches' and Silent Masses —The Converted Christians of Morocco Are Praying in Secret". www.vice.com. 23 March 2015.

- Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor(14 September 2007).

- ^ "Christianity, non-religious register biggest growth: Census 2010". Newnation.sg. 13 January 2011. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ "More People Claim Christian Faith in Japan". 19 March 2006.

- ISBN 978-9400723870.

A 2006 Gallup survey, however, is the largest to date and puts the number at 6%, which is much higher than its previous surveys. It notes a major increase among Japanese youth professing Christ.