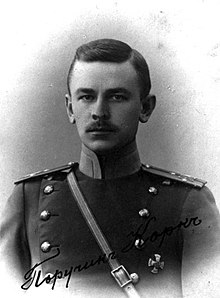

August Kork

August Kork | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 2 August [O.S. 22 July] 1887 Aardla, Kreis Dorpat, Governorate of Livonia, Russian Empire |

| Died | 11 June 1937 (aged 49) Kommunarka shooting ground, Moscow, Soviet Union |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Komandarm 2nd rank |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards |

|

| Spouse(s) | Yekaterina Mikhailovna |

August Ivanovich Kork (Russian: Август Иванович Корк, also Аугуст Яанович Корк; 2 August [O.S. 22 July] 1887 – 11 June 1937) was an Estonian Red Army commander (Komandarm 2nd rank) who was tried and executed during the Great Purge in 1937.

Kork became an officer of the

After the end of the campaign, Kork took command of the

Early life and career

Kork was born on 2 August 1887 in the village of

Kork fought in World War I on the Northwestern Front and the Western Front. In October 1914, he was awarded the Order of Saint Anna 3rd class with Swords. On 1 April 1915, he was awarded the Order of Saint Stanislaus 2nd class with Swords. Kork became an adjutant on the staff of the 3rd Siberian Army Corps and was promoted to Staff captain on 14 June. On 16 November, Kork received the Order of Saint Anna 4th class. At the same time, he became an adjutant at the headquarters of the 8th Siberian Rifle Division. On 25 or 30 December he was transferred to the 10th Army headquarters. He also served with the 20th Army Corps and the Office of the Quartermaster General on the Staff of the Western Front. On 15 August 1916, he was promoted to captain. In 1917, he graduated from the Observer-Pilot Military School. On 25 February, Kork became an officer for Aircraft Orders on the Staff of the Western Front. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel. On 31 March, Kork was awarded the Order of Saint Anna 2nd class with Swords. Between August 1917 and February 1918 he was chairman of the Soldiers' Committee of the Western Front.[2][1]

Russian Civil War

In June 1918, Kork joined the

Kork led the 15th Army in the

He became commander of the

Interwar

On 16 May 1921 Kork became commander of the

Kork was arrested on 12 May (16 May according to

Personal life

Kork married Yekaterina Mikhailovna (born 1894). In June 1937, after Kork's arrest, Yekaterina was exiled to Astrakhan, where she was arrested on 5 September. She and other wives of executed military leaders were moved back to Moscow and subjected to torture and interrogation.[11] On 13 July 1941 she was sentenced to death and was shot at the Kommunarka shooting ground on 28 July.[2]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Cherushev & Cherushev 2012, pp. 31–32.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Русская армия в Великой войне: Картотека проекта: Корк Август Иванович" [Russian Army in the Great War: Kork, August Ivanovich]. www.grwar.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2016-09-22.

- ^ Ziemke 2004, pp. 106–108.

- ^ Ziemke 2004, p. 119.

- ^ Ziemke 2004, pp. 122, 125, 129.

- ^ Ziemke 2004, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Conquest 2008, p. 194.

- ^ Conquest 2008, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Conquest 2008, pp. 203, 205.

- ^ Hiio, Toomas (1 October 2012). "Kork, August". www.estonica.org. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ Braithwaite 2010, p. 258.

References

- Braithwaite, Rodric (2010) [2006]. Moscow 1941: A City & Its People at War. London: Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-84765-062-7.

- Cherushev, Nikolai Semyonovich; Cherushev, Yury Nikolaevich (2012). Расстрелянная элита РККА (командармы 1-го и 2-го рангов, комкоры, комдивы и им равные): 1937–1941. Биографический словарь [Executed Elite of the Red Army (Komandarms of the 1st and 2nd ranks, Komkors, Komdivs, and equivalents) 1937–1941 Biographical Dictionary] (in Russian). Moscow: Kuchkovo Pole. ISBN 9785995002178.

- Conquest, Robert (2008) [1968]. The Great Terror: A Reassessment (40th Anniversary ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531699-5.

- Ziemke, Earl F. (2004). The Red Army, 1918–1941: From Vanguard of World Revolution to America's Ally. New York: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-1-135-76918-5.