Berlin

Berlin | ||

|---|---|---|

Capital city, Potsdam Square | ||

|

GeoTLD .berlin | | |

| HDI (2019) | 0.964[9] very high · 2nd of 16 | |

| Website | berlin.de | |

Berlin

Berlin was built along the banks of the Spree river, which flows into the Havel in the western borough of Spandau. The city incorporates lakes in the western and southeastern boroughs, the largest of which is Müggelsee. About one-third of the city's area is composed of forests, parks and gardens, rivers, canals, and lakes.[16]

First documented in the 13th century[11] and at the crossing of two important historic trade routes,[17] Berlin was designated the capital of the Margraviate of Brandenburg (1417–1701), Kingdom of Prussia (1701–1918), German Empire (1871–1918), Weimar Republic (1919–1933), and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). Berlin has served as a scientific, artistic, and philosophical hub during the Age of Enlightenment, Neoclassicism, and the German revolutions of 1848–1849. During the Gründerzeit, an industrialization-induced economic boom triggered a rapid population increase in Berlin. 1920s Berlin was the third-largest city in the world by population.[18]

After World War II and following Berlin's occupation, the city was split into West Berlin and East Berlin, divided by the Berlin Wall.[19] East Berlin was declared the capital of East Germany, while Bonn became the West German capital. Following German reunification in 1990, Berlin once again became the capital of all of Germany.

The

Berlin is home to several universities such as the

Berlin is also home to three

History

Margraviate of Brandenburg 1237–1618

Brandenburg-Prussia 1618–1701

Kingdom of Prussia 1701–1867

North German Confederation 1867–1871

German Empire 1871–1918

Weimar Republic 1918–1933

Nazi Germany 1933–1945

Allied-occupied Germany 1945–1949

West Germany 1949–1990

East Germany 1949–1990

Germany 1990–present

Etymology

Berlin lies in northeastern Germany. Most of the cities and villages in northeastern Germany bear

Of Berlin's twelve boroughs, five bear a Slavic-derived name: Pankow, Steglitz-Zehlendorf, Marzahn-Hellersdorf, Treptow-Köpenick, and Spandau. Of Berlin's ninety-six neighborhoods, twenty-two bear a Slavic-derived name: Altglienicke, Alt-Treptow, Britz, Buch, Buckow, Gatow, Karow, Kladow, Köpenick, Lankwitz, Lübars, Malchow, Marzahn, Pankow, Prenzlauer Berg, Rudow, Schmöckwitz, Spandau, Stadtrandsiedlung Malchow, Steglitz, Tegel and Zehlendorf.

Prehistory of Berlin

The earliest human settlements in the area of modern Berlin are dated around 60,000 BC.[citation needed] A deer mask, dated to 9,000 BC, is attributed to the Maglemosian culture. In 2,000 BC dense human settlements along the Spree and Havel rivers gave rise to the Lusatian culture.[26] Starting around 500 BC Germanic tribes settled in a number of villages in the higher situated areas of today's Berlin. After the Semnones left around 200 AD, the Burgundians followed. In the 7th century Slavic tribes, the later known Hevelli and Sprevane, reached the region.

12th century to 16th century

In the 12th century the region came under German rule as part of the

Members of the

17th to 19th centuries

The

By 1700, approximately 30 percent of Berlin's residents were French, because of the Huguenot immigration.

Since 1618, the Margraviate of Brandenburg had been in

In 1740, Frederick II, known as

The Industrial Revolution transformed Berlin during the 19th century; the city's economy and population expanded dramatically, and it became the main railway hub and economic center of Germany. Additional suburbs soon developed and increased the area and population of Berlin. In 1861, neighboring suburbs including Wedding, Moabit and several others were incorporated into Berlin.[44] In 1871, Berlin became capital of the newly founded German Empire.[45] In 1881, it became a city district separate from Brandenburg.[46]

20th to 21st centuries

In the early 20th century, Berlin had become a fertile ground for the

In 1933,

NSDAP rule diminished Berlin's Jewish community from 160,000 (one-third of all Jews in the country) to about 80,000 due to emigration between 1933 and 1939. After

Berlin hosted the 1936 Summer Olympics for which the Olympic stadium was built.[52]

During World War II, Berlin was the location of multiple Nazi prisons, forced labour camps, 17 subcamps of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp for men and women, including teenagers, of various nationalities, including Polish, Jewish, French, Belgian, Czechoslovak, Russian, Ukrainian, Romani, Dutch, Greek, Norwegian, Spanish, Luxembourgish, German, Austrian, Italian, Yugoslavian, Bulgarian, Hungarian,[53] a camp for Sinti and Romani people (see Romani Holocaust),[54] and the Stalag III-D prisoner-of-war camp for Allied POWs of various nationalities.

During World War II, large parts of Berlin were destroyed during 1943–45 Allied air raids and the 1945 Battle of Berlin. The Allies dropped 67,607 tons of bombs on the city, destroying 6,427 acres of the built-up area. Around 125,000 civilians were killed.[55] After the end of World War II in Europe in May 1945, Berlin received large numbers of refugees from the Eastern provinces. The victorious powers divided the city into four sectors, analogous to Allied-occupied Germany the sectors of the Allies of World War II (the United States, the United Kingdom, and France) formed West Berlin, while the Soviet Union formed East Berlin.[56]

All four Allies of World War II shared administrative responsibilities for Berlin. However, in 1948, when the Western Allies extended the currency reform in the Western zones of Germany to the three western sectors of Berlin, the

The founding of the two German states increased Cold War tensions. West Berlin was surrounded by East German territory, and East Germany proclaimed the Eastern part as its capital, a move the western powers did not recognize. East Berlin included most of the city's historic center. The West German government established itself in Bonn.[58] In 1961, East Germany began to build the Berlin Wall around West Berlin, and events escalated to a tank standoff at Checkpoint Charlie. West Berlin was now de facto a part of West Germany with a unique legal status, while East Berlin was de facto a part of East Germany. John F. Kennedy gave his "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech on 26 June 1963, in front of the Schöneberg city hall, located in the city's western part, underlining the US support for West Berlin.[59] Berlin was completely divided. Although it was possible for Westerners to pass to the other side through strictly controlled checkpoints, for most Easterners, travel to West Berlin or West Germany was prohibited by the government of East Germany. In 1971, a Four-Power agreement guaranteed access to and from West Berlin by car or train through East Germany.[60]

In 1989, with the end of the Cold War and pressure from the East German population, the Berlin Wall fell on 9 November and was subsequently mostly demolished. Today, the East Side Gallery preserves a large portion of the wall. On 3 October 1990, the two parts of Germany were reunified as the Federal Republic of Germany, and Berlin again became a reunified city. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the city experienced significant urban development and still impacts urban planning decisions.

[61] Walter Momper, the mayor of West Berlin, became the first mayor of the reunified city in the interim.[62] City-wide elections in December 1990 resulted in the first "all Berlin" mayor being elected to take office in January 1991, with the separate offices of mayors in East and West Berlin expiring by that time, and Eberhard Diepgen (a former mayor of West Berlin) became the first elected mayor of a reunited Berlin.[63] On 18 June 1994, soldiers from the United States, France and Britain marched in a parade which was part of the ceremonies to mark the withdrawal of allied occupation troops allowing a reunified Berlin[64] (the last Russian troops departed on 31 August, while the final departure of Western Allies forces was on 8 September 1994). On 20 June 1991, the Bundestag (German Parliament) voted to move the seat of the German capital from Bonn to Berlin, which was completed in 1999, during the chancellorship of Gerhard Schröder.[65]

In 2006, the

Construction of the "Berlin Wall Trail" (Berliner Mauerweg) began in 2002 and was completed in 2006.

In a

In 2018, more than 200,000 protestors took to the streets in Berlin with demonstrations of solidarity against racism, in response to the emergence of

A partial opening by the end of 2020 of the Humboldt Forum museum, housed in the reconstructed Berlin Palace, which had been announced in June, was postponed until March 2021.[74] On 16 September 2022, the opening of the eastern wing, the last section of the Humboldt Forum museum, meant the Humboldt Forum museum was finally completed. It became Germany's currently most expensive cultural project.[75]

Berlin-Brandenburg fusion attempt

The legal basis for a combined state of Berlin and Brandenburg is different from other state fusion proposals. Normally, Article 29 of the Basic Law stipulates that a state fusion requires a federal law.[76] However, a clause added to the Basic Law in 1994, Article 118a, allows Berlin and Brandenburg to unify without federal approval, requiring a referendum and a ratification by both state parliaments.[77]

In 1996, there was an unsuccessful attempt of unifying the states of Berlin and Brandenburg.[78] Both share a common history, dialect and culture and in 2020, there are over 225.000 residents of Brandenburg that commute to Berlin. The fusion had the near-unanimous support by a broad coalition of both state governments, political parties, media, business associations, trade unions and churches.[79] Though Berlin voted in favor by a small margin, largely based on support in former West Berlin, Brandenburg voters disapproved of the fusion by a large margin. It failed largely due to Brandenburg voters not wanting to take on Berlin's large and growing public debt and fearing losing identity and influence to the capital.[78]

Geography

Topography

Berlin is in northeastern Germany, in an area of low-lying marshy woodlands with a mainly flat

Substantial parts of present-day Berlin extend onto the low plateaus on both sides of the Spree Valley. Large parts of the boroughs Reinickendorf and Pankow lie on the Barnim Plateau, while most of the boroughs of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf, Steglitz-Zehlendorf, Tempelhof-Schöneberg, and Neukölln lie on the Teltow Plateau.

The borough of Spandau lies partly within the Berlin Glacial Valley and partly on the Nauen Plain, which stretches to the west of Berlin. Since 2015, the Arkenberge hills in Pankow at 122 meters (400 ft) elevation, have been the highest point in Berlin. Through the disposal of construction debris they surpassed Teufelsberg (120.1 m or 394 ft), which itself was made up of rubble from the ruins of the Second World War.[81] The Müggelberge at 114.7 meters (376 ft) elevation is the highest natural point and the lowest is the Spektesee in Spandau, at 28.1 meters (92 ft) elevation.[82]

Climate

Berlin has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb)[83] bordering on a humid continental climate (Dfb). This type of climate features mild to very warm summer temperatures and cold, though not very severe, winters. Annual precipitation is modest.[84][85]

Frosts are common in winter, and there are larger temperature differences between seasons than typical for many oceanic climates. Summers are warm and sometimes humid with average high temperatures of 22–25 °C (72–77 °F) and lows of 12–14 °C (54–57 °F). Winters are cold with average high temperatures of 3 °C (37 °F) and lows of −2 to 0 °C (28 to 32 °F). Spring and autumn are generally chilly to mild. Berlin's built-up area creates a microclimate, with heat stored by the city's buildings and pavement. Temperatures can be 4 °C (7 °F) higher in the city than in the surrounding areas.[86] Annual precipitation is 570 millimeters (22 in) with moderate rainfall throughout the year. Snowfall mainly occurs from December through March.[87] The hottest month in Berlin was July 1834, with a mean temperature of 23.0 °C (73.4 °F) and the coldest was January 1709, with a mean temperature of −13.2 °C (8.2 °F).[88] The wettest month on record was July 1907, with 230 millimeters (9.1 in) of rainfall, whereas the driest were October 1866, November 1902, October 1908 and September 1928, all with 1 millimeter (0.039 in) of rainfall.[89]

| Climate data for Berlin (Brandenburg), 1991–2020, extremes 1957–2021 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.1 (59.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

25.8 (78.4) |

30.8 (87.4) |

32.7 (90.9) |

38.4 (101.1) |

38.3 (100.9) |

38.0 (100.4) |

32.3 (90.1) |

27.7 (81.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

38.4 (101.1) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 10.6 (51.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

28.4 (83.1) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.7 (90.9) |

32.7 (90.9) |

26.9 (80.4) |

21.5 (70.7) |

14.8 (58.6) |

11.2 (52.2) |

34.8 (94.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

4.9 (40.8) |

9.0 (48.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.9 (73.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.8 (76.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

13.9 (57.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.1 (39.4) |

14.2 (57.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

1.6 (34.9) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.6 (63.7) |

19.6 (67.3) |

19.2 (66.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.8 (35.2) |

9.9 (49.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.2 (28.0) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

0.4 (32.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

8.2 (46.8) |

11.7 (53.1) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

5.6 (42.1) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

5.3 (41.6) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −12.0 (10.4) |

−9.5 (14.9) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

1.7 (35.1) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.9 (48.0) |

8.1 (46.6) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.3 (−13.5) |

−22.0 (−7.6) |

−19.1 (−2.4) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

1.3 (34.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

4.6 (40.3) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−7.7 (18.1) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−24.0 (−11.2) |

−25.3 (−13.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41.5 (1.63) |

30.0 (1.18) |

35.9 (1.41) |

27.7 (1.09) |

52.8 (2.08) |

60.2 (2.37) |

70.0 (2.76) |

52.4 (2.06) |

43.6 (1.72) |

40.3 (1.59) |

38.8 (1.53) |

39.1 (1.54) |

532.3 (20.96) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 15.8 | 13.9 | 14 | 10.9 | 12.8 | 12.4 | 13.4 | 12.7 | 11.6 | 13.6 | 14.5 | 16.4 | 162 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1.0 cm) | 8.4 | 6.8 | 2.6 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.4 | 4.9 | 24.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%)

|

85.9 | 81.2 | 75.8 | 67.2 | 66.9 | 66.3 | 67 | 68.5 | 76 | 82.7 | 87.8 | 87.5 | 76.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 52.6 | 77.9 | 126.7 | 196.4 | 231.1 | 232.9 | 233.7 | 222.2 | 168.9 | 113.8 | 57.4 | 45.0 | 1,758.6 |

| Source 1: Data derived from Deutscher Wetterdienst[90] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NCEI(days with precipitation and snow, humidity)[91]

| |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Berlin (Dahlem), 58 m or 190 ft, 1961–1990 normals, extremes 1908–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

25.1 (77.2) |

30.9 (87.6) |

33.3 (91.9) |

36.1 (97.0) |

37.9 (100.2) |

37.7 (99.9) |

34.2 (93.6) |

27.5 (81.5) |

19.5 (67.1) |

15.7 (60.3) |

37.9 (100.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

3.5 (38.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

18.6 (65.5) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.8 (73.0) |

18.7 (65.7) |

13.3 (55.9) |

7.0 (44.6) |

3.2 (37.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.4 (31.3) |

0.6 (33.1) |

4.0 (39.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.7 (62.1) |

17.9 (64.2) |

17.2 (63.0) |

13.5 (56.3) |

9.3 (48.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

1.2 (34.2) |

8.9 (48.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.9 (26.8) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

0.5 (32.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

12.9 (55.2) |

12.4 (54.3) |

9.4 (48.9) |

5.9 (42.6) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

5.0 (41.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −21.0 (−5.8) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

−16.5 (2.3) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

0.8 (33.4) |

5.4 (41.7) |

4.7 (40.5) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 43.0 (1.69) |

37.0 (1.46) |

38.0 (1.50) |

42.0 (1.65) |

55.0 (2.17) |

71.0 (2.80) |

53.0 (2.09) |

65.0 (2.56) |

46.0 (1.81) |

36.0 (1.42) |

50.0 (1.97) |

55.0 (2.17) |

591 (23.29) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 11.0 | 112 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 45.4 | 72.3 | 122.0 | 157.7 | 221.6 | 220.9 | 217.9 | 210.2 | 156.3 | 110.9 | 52.4 | 37.4 | 1,625 |

| Source 1: NOAA[92] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Berliner Extremwerte[93] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Berlin's history has left the city with a polycentric metropolitan area and an eclectic mix of architecture. The city's appearance today has been predominantly shaped by German history during the 20th century. 17% of Berlin's buildings are Gründerzeit or earlier and nearly 25% are of the 1920s and 1930s, when Berlin played a part in the origin of modern architecture.[94][95]

Devastated by the

The list of tallest buildings in Berlin spreads across the urban area, they can be found for example at Potsdamer Platz, the City West, and Alexanderplatz.

Over one-third of the city area consists of green space, woodlands, and water.

Architecture

The

The

The East Side Gallery is an open-air exhibition of art painted directly on the last existing portions of the Berlin Wall. It is the largest remaining evidence of the city's historical division.

The

The

The area around

The

The

West of the center,

The

The

Demographics

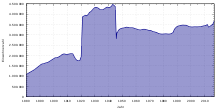

At the end of 2018, the city-state of Berlin had 3.75 million registered inhabitants

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1721 | 65,300 | — |

| 1750 | 113,289 | +73.5% |

| 1800 | 172,132 | +51.9% |

| 1815 | 197,717 | +14.9% |

| 1825 | 220,277 | +11.4% |

| 1840 | 330,230 | +49.9% |

| 1852 | 438,958 | +32.9% |

| 1861 | 547,571 | +24.7% |

| 1871 | 826,341 | +50.9% |

| 1880 | 1,122,330 | +35.8% |

| 1890 | 1,578,794 | +40.7% |

| 1900 | 1,888,848 | +19.6% |

| 1910 | 2,071,257 | +9.7% |

| 1920 | 3,879,409 | +87.3% |

| 1925 | 4,082,778 | +5.2% |

| 1933 | 4,221,024 | +3.4% |

| 1939 | 4,330,640 | +2.6% |

| 1945 | 3,064,629 | −29.2% |

| 1950 | 3,336,026 | +8.9% |

| 1960 | 3,274,016 | −1.9% |

| 1970 | 3,208,719 | −2.0% |

| 1980 | 3,048,759 | −5.0% |

| 1990 | 3,433,695 | +12.6% |

| 2000 | 3,382,169 | −1.5% |

| 2010 | 3,460,725 | +2.3% |

| 2020 | 3,664,088 | +5.9% |

| 2022 | 3,755,251 | +2.5% |

| Population size may be affected by changes in administrative divisions. | ||

In 2014, the city-state Berlin had 37,368 live births (+6.6%), a record number since 1991. The number of deaths was 32,314. Almost 2.0 million households were counted in the city. 54 percent of them were single-person households. More than 337,000 families with children under the age of 18 lived in Berlin. In 2014, the German capital registered a migration surplus of approximately 40,000 people.[103]

Nationalities

| Country | Population |

|---|---|

| 2,958,786 | |

| 99,421 | |

| 53,664 | |

| 49,280 | |

| 44,324 | |

| 32,362 | |

| 32,170 | |

| 30,590 | |

| 27,128 | |

| 23,771 | |

| 22,858 | |

| 20,990 | |

| 20,567 | |

| 19,241 | |

| 17,481 |

National and international migration into the city has a long history. In 1685, after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in France, the city responded with the Edict of Potsdam, which guaranteed religious freedom and tax-free status to French Huguenot refugees for ten years. The Greater Berlin Act in 1920 incorporated many suburbs and surrounding cities of Berlin. It formed most of the territory that comprises modern Berlin and increased the population from 1.9 million to 4 million.

Active immigration and asylum politics in West Berlin triggered waves of immigration in the 1960s and 1970s. Berlin is home to at least 180,000

In December 2019 there were 777,345 registered residents of foreign nationality and another 542,975 German citizens with a "migration background" (Migrationshintergrund, MH),[100] meaning they or one of their parents immigrated to Germany after 1955. Foreign residents of Berlin originate from about 190 countries.[109] 48 percent of the residents under the age of 15 have a migration background in 2017.[110] Berlin in 2009 was estimated to have 100,000 to 250,000 unregistered inhabitants.[111] Boroughs of Berlin with a significant number of migrants or foreign born population are Mitte, Neukölln and Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg.[112] The number of Arabic speakers in Berlin could be higher than 150,000. There are at least 40,000 Berliners with Syrian citizenship, third only behind Turkish and Polish citizens. The 2015 refugee crisis made Berlin Europe's capital of Arab culture.[113] Berlin is among the cities in Germany that have received the biggest amount of refugees after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. As of November 2022, an estimated 85,000 Ukrainian refugees were registered in Berlin,[114] making Berlin the most popular destination of Ukrainian refugees in Germany.[115]

Berlin has a vibrant expatriate community involving precarious immigrants, illegal immigrants, seasonal workers, and refugees. Therefore, Berlin sustains a broad variety of English-based speakers. Speaking a particular type of English does attract prestige and cultural capital in Berlin.[116]

Languages

German is the official and predominant spoken language in Berlin. It is a West Germanic language that derives most of its vocabulary from the Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family. German is one of 24 languages of the European Union,[117] and one of the three working languages of the European Commission.

Berlinerisch or Berlinisch is not a dialect linguistically. It is spoken in Berlin and the

The most commonly spoken foreign languages in Berlin are Turkish, Polish, English, Persian, Arabic, Italian, Bulgarian, Russian, Romanian, Kurdish, Serbo-Croatian, French, Spanish and Vietnamese. Turkish, Arabic, Kurdish, and Serbo-Croatian are heard more often in the western part due to the large Middle Eastern and former-Yugoslavian communities. Polish, English, Russian, and Vietnamese have more native speakers in East Berlin.[118]

Religion

On the report of the 2011 census, approximately 37 percent of the population reported being members of a legally-recognized church or religious organization. The rest either did not belong to such an organization, or there was no information available about them.[120]

The largest religious denomination recorded in 2010 was the

In 2009, approximately 249,000

About 0.9% of Berliners belong to other religions. Of the estimated population of 30,000–45,000 Jewish residents,[127] approximately 12,000 are registered members of religious organizations.[122]

Berlin is the seat of the

The faithful of the different religions and denominations maintain many

Government and politics

German federal city state

Since the

The total annual budget of Berlin in 2015 exceeded €24.5 ($30.0) billion including a budget surplus of €205 ($240) million.[132] The German Federal city state of Berlin owns extensive assets, including administrative and government buildings, real estate companies, as well as stakes in the Olympic Stadium, swimming pools, housing companies, and numerous public enterprises and subsidiary companies.[133][134] The federal state of Berlin runs a real estate portal to advertise commercial spaces or land suitable for redevelopment.[135]

The

The Governing Mayor is simultaneously Lord Mayor of the City of Berlin (Oberbürgermeister der Stadt) and Minister President of the State of Berlin (Ministerpräsident des Bundeslandes). The office of the Governing Mayor is in the Rotes Rathaus (Red City Hall). Since 2023, this office has been held by Kai Wegner of the Christian Democrats.[138] He is the first conservative mayor in Berlin in more than two decades.[139]

Boroughs

Berlin is subdivided into 12 boroughs or districts (Bezirke). Each borough has several subdistricts or neighborhoods (Ortsteile), which have roots in much older municipalities that predate the formation of Greater Berlin on 1 October 1920. These subdistricts became urbanized and incorporated into the city later on. Many residents strongly identify with their neighborhoods, colloquially called Kiez. At present, Berlin consists of 96 subdistricts, which are commonly made up of several smaller residential areas or quarters.

Each borough is governed by a borough council (Bezirksamt) consisting of five councilors (Bezirksstadträte) including the borough's mayor (Bezirksbürgermeister). The council is elected by the borough assembly (Bezirksverordnetenversammlung). However, the individual boroughs are not independent municipalities, but subordinate to the Senate of Berlin. The borough's mayors make up the council of mayors (Rat der Bürgermeister), which is led by the city's Governing Mayor and advises the Senate. The neighborhoods have no local government bodies.

City partnerships

Berlin to this day maintains official partnerships with 17 cities.[140] Town twinning between West Berlin and other cities began with its sister city Los Angeles, California, in 1967. East Berlin's partnerships were canceled at the time of German reunification.

Capital city

Berlin is the capital of the Federal Republic of Germany. The

-

TheChancellor of Germany

-

Schloss Bellevue, seat of the President of Germany

-

Bundesrat of Germany

The relocation of the federal government and Bundestag to Berlin was mostly completed in 1999. However, some ministries, as well as some minor departments, stayed in the federal city Bonn, the former capital of West Germany. Discussions about moving the remaining ministries and departments to Berlin continue.[143]

The

Embassies

Berlin hosts in total 158 foreign embassies[144] as well as the headquarters of many think tanks, trade unions, nonprofit organizations, lobbying groups, and professional associations. Frequent official visits and diplomatic consultations among governmental representatives and national leaders are common in contemporary Berlin.

Economy

In 2018, the GDP of Berlin totaled €147 billion, an increase of 3.1% over the previous year.

Important economic sectors in Berlin include life sciences, transportation, information and communication technologies, media and music, advertising and design, biotechnology, environmental services, construction, e-commerce, retail, hotel business, and medical engineering.[148]

Research and development have economic significance for the city.[149] Several major corporations like Volkswagen, Pfizer, and SAP operate innovation laboratories in the city.[150] The Science and Business Park in Adlershof is the largest technology park in Germany measured by revenue.[151] Within the Eurozone, Berlin has become a center for business relocation and international investments.[152][153]

| Year[154] | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment rate in % | 13.6 | 13.3 | 12.3 | 11.7 | 11.1 | 10.7 | 9.8 | 9.0 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 6.4 | 8.6 | 9.1 |

Companies

Many German and international companies have business or service centers in the city. For several years Berlin has been recognized as a major center of business founders.[156] In 2015, Berlin generated the most venture capital for young startup companies in Europe.[157]

Among the 10 largest employers in Berlin are the City-State of Berlin,

Siemens, a Global 500 and DAX-listed company is partly headquartered in Berlin. Other DAX-listed companies headquartered in Berlin are the property company Deutsche Wohnen and the online food delivery service Delivery Hero. The national railway operator Deutsche Bahn,[160] Europe's largest digital publisher[161] Axel Springer as well as the MDAX-listed firms Zalando and HelloFresh and also have their main headquarters in the city. Among the largest international corporations who have their German or European headquarters in Berlin are Bombardier Transportation, Securing Energy for Europe, Coca-Cola, Pfizer, Sony and TotalEnergies.

As of 2023,

Mercedes-Benz Group manufactures cars, and BMW builds motorcycles in Berlin. In 2022, American electric car manufacturer Tesla opened its first European Gigafactory outside the city borders in Grünheide (Mark), Brandenburg. The Pharmaceuticals division of Bayer[164] and Berlin Chemie are major pharmaceutical companies in the city.

Tourism and conventions

Berlin had 788 hotels with 134,399 beds in 2014.

According to figures from the International Congress and Convention Association in 2015, Berlin became the leading organizer of conferences globally, hosting 195 international meetings.[166] Some of these congress events take place on venues such as CityCube Berlin or the Berlin Congress Center (bcc).

The Messe Berlin (also known as Berlin ExpoCenter City) is the main convention organizing company in the city. Its main exhibition area covers more than 160,000 square meters (1,722,226 sq ft). Several large-scale trade fairs like the consumer electronics trade fair IFA, where the first practical audio tape recorder and the first completely electronic television system were first introduced to the public,[167][168][169][170] the ILA Berlin Air Show, the Berlin Fashion Week (including the Premium Berlin and the Panorama Berlin),[171] the Green Week, the Fruit Logistica, the transport fair InnoTrans, the tourism fair ITB and the adult entertainment and erotic fair Venus are held annually in the city, attracting a significant number of business visitors.

Creative industries

The

In 2014, around 30,500 creative companies operated in the Berlin-Brandenburg metropolitan region, predominantly SMEs. Generating a revenue of 15.6 billion Euro and 6% of all private economic sales, the culture industry grew from 2009 to 2014 at an average rate of 5.5% per year.[173]

Berlin is an important European and

Media

Berlin is home to many magazine, newspaper, book, and scientific/academic publishers and their associated service industries. In addition, around 20 news agencies, more than 90 regional daily newspapers and their websites, as well as the Berlin offices of more than 22 national publications such as Der Spiegel, and Die Zeit reinforce the capital's position as Germany's epicenter for influential debate. Therefore, many international journalists, bloggers, and writers live and work in the city.

Berlin is the central location to several international and regional television and radio stations.

Berlin has Germany's largest number of daily newspapers, with numerous local broadsheets (Berliner Morgenpost, Berliner Zeitung, Der Tagesspiegel), and three major tabloids, as well as national dailies of varying sizes, each with a different political affiliation, such as Die Welt, Neues Deutschland, and Die Tageszeitung. The Exberliner, a monthly magazine, is Berlin's English-language periodical and La Gazette de Berlin a French-language newspaper.

Berlin is also the headquarter of major German-language publishing houses like

Quality of life

According to Mercer, Berlin ranked number 13 in the Quality of living city ranking in 2019.[176]

Also in 2019, according to

Transport in Berlin

Roads

Berlin's transport infrastructure provides a diverse range of urban mobility.[181]

A total of 979 bridges cross 197 km (122 miles) the inner-city waterways. Berlin roads total 5,422 km (3,369 miles) of which 77 km (48 miles) are motorways (known as Autobahn).[182] The AVUS was the first automobile-only road[183] and served as an inspiration for the first motorways in the world.[184][185] In 2013 only 1.344 million motor vehicles were registered in the city.[182] With 377 cars per 1000 residents in 2013 (570/1000 in Germany), Berlin as a Western global city has one of the lowest numbers of cars per capita.[186]

Cycling

Berlin is well known for its highly developed

Cyclists in Berlin have access to 620 km of bicycle paths including approximately 150 km of mandatory bicycle paths, 190 km of off-road bicycle routes, 60 km of bicycle lanes on roads, 70 km of shared bus lanes which are also open to cyclists, 100 km of combined pedestrian/bike paths and 50 km of marked bicycle lanes on roadside pavements or sidewalks.[189] Riders are allowed to carry their bicycles on Regionalbahn (RE), S-Bahn and U-Bahn trains, on trams, and on night buses if a bike ticket is purchased.[190]

Taxicabs

In 2012 around 7,600 mostly colored

Rail

Long-distance rail lines directly connect Berlin with all of the major cities of Germany. the regional rail lines of the

Water transport

The Spree and the Havel rivers cross Berlin. There are no frequent passenger connections to and from Berlin by water. Berlin's largest harbour, the Westhafen, is located in the district of Moabit. It is a transhipment and storage site for inland shipping with a growing importance.[192]

Intercity buses

There is an increasing quantity of intercity bus services. Berlin city has more than 10 stations[193] that run buses to destinations throughout Berlin. Destinations in Germany and Europe are connected via the intercity bus exchange Zentraler Omnibusbahnhof Berlin.

Urban public transport

The Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG) and the German State-owned Deutsche Bahn (DB) manage several extensive urban public transport systems.[194]

| System | Stations / Lines / Net length | Annual ridership | Operator / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-Bahn | 166 / 16 / 331 km (206 mi) | 431,000,000 (2016) | DB / Mainly overground rapid transit rail system with suburban stops |

| U-Bahn | 173 / 9 / 146 km (91 mi) | 563,000,000 (2017) | BVG / Mainly underground rail system / 24h-service on weekends |

Tram

|

404 / 22 / 194 km (121 mi) | 197,000,000 (2017) | BVG / Operates predominantly in eastern boroughs |

| Bus | 3227 / 198 / 1,675 km (1,041 mi) | 440,000,000 (2017) | BVG / Extensive services in all boroughs / 62 Night Lines |

| Ferry | 6 lines | BVG / Transportation as well as recreational ferries |

Public transport in Berlin has a long and complicated history because of the 20th-century division of the city, where movement between the two halves was not served. Since 1989, the transport network has been developed extensively. However, it still contains early 20th century traits, such as the U1.[195]

Airports

Berlin is served by one commercial international airport: Berlin Brandenburg Airport (BER), located just outside Berlin's south-eastern border, in the state of Brandenburg. It began construction in 2006, with the intention of replacing Tegel Airport (TXL) and Schönefeld Airport (SXF) as the single commercial airport of Berlin.[196] Previously set to open in 2012, after extensive delays and cost overruns, it opened for commercial operations in October 2020.[197] The planned initial capacity of around 27 million passengers per year[198] is to be further developed to bring the terminal capacity to approximately 55 million per year by 2040.[199]

Before the opening of the BER in Brandenburg, Berlin was served by Tegel Airport and Schönefeld Airport. Tegel Airport was within the city limits, and Schönefeld Airport was located at the same site as the BER. Both airports together handled 29.5 million passengers in 2015. In 2014, 67 airlines served 163 destinations in 50 countries from Berlin.

Rohrpost

From 1865 to 1976, Berlin operated an expansive pneumatic postal network, reaching a maximum length of 400 kilometers (roughly 250 miles) by 1940. The system was divided into two distinct networks after 1949. The West Berlin system remained in public use until 1963, and continued to be utilized for government correspondence until 1972. Conversely, the East Berlin system, which incorporated the Hauptelegraphenamt—the central hub of the operation—remained functional until 1976.

Energy

Berlin's two largest energy provider for private households are the Swedish firm Vattenfall and the Berlin-based company GASAG. Both offer electric power and natural gas supply. Some of the city's electric energy is imported from nearby power plants in southern Brandenburg.[201]

As of 2015[update] the five largest power plants measured by capacity are the Heizkraftwerk Reuter West, the Heizkraftwerk Lichterfelde, the Heizkraftwerk Mitte, the Heizkraftwerk Wilmersdorf, and the Heizkraftwerk Charlottenburg. All of these power stations generate electricity and useful heat at the same time to facilitate buffering during load peaks.

In 1993 the power grid connections in the Berlin-Brandenburg capital region were renewed. In most of the inner districts of Berlin power lines are underground cables; only a 380 kV and a 110 kV line, which run from Reuter substation to the urban Autobahn, use overhead lines. The Berlin 380-kV electric line is the backbone of the city's energy grid.

Health

Berlin has a long history of discoveries in medicine and innovations in medical technology.[202] The modern history of medicine has been significantly influenced by scientists from Berlin. Rudolf Virchow was the founder of cellular pathology, while Robert Koch developed vaccines for anthrax, cholera, and tuberculosis.[203] For his life's work Koch is seen as one of the founders of modern medicine.[204]

The

Telecommunication

Since 2017, the

.Berlin has installed several hundred free public Wireless LAN sites across the capital since 2016. The wireless networks are concentrated mostly in central districts; 650 hotspots (325 indoor and 325 outdoor access points) are installed.[206]

The UMTS (3G) and LTE (4G) networks of the three major cellular operators Vodafone, T-Mobile and O2 enable the use of mobile broadband applications citywide.

Education and research

As of 2014[update], Berlin had 878 schools, teaching 340,658 students in 13,727 classes and 56,787 trainees in businesses and elsewhere.[149] The city has a 6-year primary education program. After completing primary school, students continue to the Sekundarschule (a comprehensive school) or Gymnasium (college preparatory school). Berlin has a special bilingual school program in the Europaschule, in which children are taught the curriculum in German and a foreign language, starting in primary school and continuing in high school.[208]

The

Higher education

The Berlin-Brandenburg capital region is one of the most prolific centers of higher education and research in Germany and Europe. Historically, 67 Nobel Prize winners are affiliated with the Berlin-based universities.

The city has four public research universities and more than 30 private, professional, and technical colleges (Hochschulen), offering a wide range of disciplines.[212] A record number of 175,651 students were enrolled in the winter term of 2015/16.[213] Among them around 18% have an international background.

The three largest universities combined have approximately 103,000 enrolled students. There are the

Research

The city has a high density of internationally renowned research institutions, such as the

Berlin is one of the knowledge and innovation communities (KIC) of the

One of Europe's successful research, business and technology

In addition to the university-affiliated libraries, the

Culture

Berlin is known for its numerous cultural institutions, many of which enjoy international reputation.[24][224] The diversity and vivacity of the metropolis led to a trendsetting atmosphere.[225] An innovative music, dance and art scene has developed in the 21st century.

Young people, international artists and entrepreneurs continued to settle in the city and made Berlin a popular entertainment center in the world.[226]

The expanding cultural performance of the city was underscored by the relocation of the Universal Music Group who decided to move their headquarters to the banks of the River Spree.[227] In 2005, Berlin was named "City of Design" by UNESCO and has been part of the Creative Cities Network ever since.[228][21]

Many German and International films were shot in Berlin, including

Galleries and museums

As of 2011[update] Berlin is home to 138 museums and more than 400 art galleries.[149] [229] The ensemble on the Museum Island is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is in the northern part of the Spree Island between the Spree and the Kupfergraben.[24] As early as 1841 it was designated a "district dedicated to art and antiquities" by a royal decree. Subsequently, the Altes Museum was built in the Lustgarten. The Neues Museum, which displays the bust of Queen Nefertiti,[230] Alte Nationalgalerie, Pergamon Museum, and Bode Museum were built there.

Apart from the Museum Island, there are many additional museums in the city. The

The

In Dahlem, there are several museums of world art and culture, such as the Museum of Asian Art, the Ethnological Museum, the Museum of European Cultures, as well as the Allied Museum. The Brücke Museum features one of the largest collection of works by artist of the early 20th-century expressionist movement. In Lichtenberg, on the grounds of the former East German Ministry for State Security, is the Stasi Museum. The site of Checkpoint Charlie, one of the most renowned crossing points of the Berlin Wall, is still preserved. A private museum venture exhibits a comprehensive documentation of detailed plans and strategies devised by people who tried to flee from the East.

The Beate Uhse Erotic Museum claimed to be the largest erotic museum in the world until it closed in 2014.[236][237]

The cityscape of Berlin displays large quantities of urban street art.[238] It has become a significant part of the city's cultural heritage and has its roots in the graffiti scene of Kreuzberg of the 1980s.[239] The Berlin Wall itself has become one of the largest open-air canvasses in the world.[240] The leftover stretch along the Spree river in Friedrichshain remains as the East Side Gallery. Berlin today is consistently rated as an important world city for street art culture.[241] Berlin has galleries which are quite rich in contemporary art. Located in Mitte, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, KOW, Sprüth Magers; Kreuzberg there are a few galleries as well such as Blain Southern, Esther Schipper, Future Gallery, König Gallerie.

Nightlife and festivals

Berlin's nightlife has been celebrated as one of the most diverse and vibrant of its kind.

Clubs are not required to close at a fixed time during the weekends, and many parties last well into the morning or even all weekend. The Weekend Club near

Berlin has a long history of gay culture, and is an important birthplace of the LGBT rights movement. Same-sex bars and dance halls operated freely as early as the 1880s, and the first gay magazine, Der Eigene, started in 1896. By the 1920s, gays and lesbians had an unprecedented visibility.[245][246] Today, in addition to a positive atmosphere in the wider club scene, the city again has a huge number of queer clubs and festivals. The most famous and largest are Berlin Pride, the Christopher Street Day,[247] the Lesbian and Gay City Festival in Berlin-Schöneberg, the Kreuzberg Pride.

The annual

Performing arts

Berlin is home to 44 theaters and stages.[149] The Deutsches Theater in Mitte was built in 1849–50 and has operated almost continuously since then. The Volksbühne at Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz was built in 1913–14, though the company had been founded in 1890. The Berliner Ensemble, famous for performing the works of Bertolt Brecht, was established in 1949. The Schaubühne was founded in 1962 and moved to the building of the former Universum Cinema on Kurfürstendamm in 1981. With a seating capacity of 1,895 and a stage floor of 2,854 square meters (30,720 sq ft), the Friedrichstadt-Palast in Berlin Mitte is the largest show palace in Europe. For Berlin's independent dance and theatre scene, venues such as the Sophiensäle in Mitte and the three houses of the Hebbel am Ufer (HAU) in Kreuzberg are important. Most productions there are also accessible to an English-speaking audience. Some of the dance and theatre groups that also work internationally (Gob Squad, Rimini Protokoll) are based there, as well as festivals such as the international festival Dance in August.

Berlin has three major

The city's main venue for musical theater performances are the Theater am Potsdamer Platz and Theater des Westens (built in 1895). Contemporary dance can be seen at the Radialsystem V. The Tempodrom is host to concerts and circus-inspired entertainment. It also houses a multi-sensory spa experience. The Admiralspalast in Mitte has a vibrant program of variety and music events.

There are seven symphony orchestras in Berlin. The

Cuisine

The cuisine and culinary offerings of Berlin vary greatly. 23 restaurants in Berlin have been awarded one or more Michelin stars in the Michelin Guide of 2021, which ranks the city at the top for the number of restaurants having this distinction in Germany.[257] Berlin is well known for its offerings of vegetarian[258] and vegan[259] cuisine and is home to an innovative entrepreneurial food scene promoting cosmopolitan flavors, local and sustainable ingredients, pop-up street food markets, supper clubs, as well as food festivals, such as Berlin Food Week.[260][261]

Many local foods originated from north German culinary traditions and include rustic and hearty dishes with pork, goose, fish, peas, beans, cucumbers, or potatoes. Typical Berliner fare include popular

Berlin is also home to a diverse gastronomy scene reflecting the immigrant history of the city. Turkish and Arab immigrants brought their culinary traditions to the city, such as the

Recreation

The Tiergarten park in Mitte, with landscape design by Peter Joseph Lenné, is one of Berlin's largest and most popular parks.[270] In Kreuzberg, the Viktoriapark provides a viewing point over the southern part of inner-city Berlin. Treptower Park, beside the Spree in Treptow, features a large Soviet War Memorial. The Volkspark in Friedrichshain, which opened in 1848, is the oldest park in the city, with monuments, a summer outdoor cinema and several sports areas.[271] Tempelhofer Feld, the site of the former city airport, is the world's largest inner-city open space.[272]

Potsdam is on the southwestern periphery of Berlin. The city was a residence of the Prussian kings and the German Kaiser, until 1918. The area around Potsdam in particular Sanssouci is known for a series of interconnected lakes and cultural landmarks. The Palaces and Parks of Potsdam and Berlin are the largest World Heritage Site in Germany.[273]

Berlin is also well known for its numerous cafés, street musicians, beach bars along the Spree River, flea markets, boutique shops and

Sports

Berlin has established a high-profile as a host city of major international sporting events.

Berlin host the 2023 Special Olympics World Summer Games. This is the first time Germany has ever hosted the Special Olympics World Games.[279]

The annual

Several professional clubs representing the most important spectator team sports in Germany have their base in Berlin. The oldest and most popular first division team based in Berlin is the football club Hertha BSC.[290] The team represented Berlin as a founding member of the Bundesliga in 1963. Other professional team sport clubs include:

| Club(s) | Sport(s) | Founded | League(s) | Venue(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. FC Union Berlin[291] | Football | 1966 | Bundesliga | Stadion An der Alten Försterei |

| Hertha BSC[290] | Football | 1892 | 2. Bundesliga | Olympiastadion

|

ALBA Berlin[292]

|

Basketball | 1991 | BBL | Uber Arena |

| Berlin Thunder[293] | American football | 2021 | ELF | Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark |

| Eisbären Berlin[294] | Ice hockey | 1954 | DEL | Uber Arena |

| Füchse Berlin[295] | Handball

|

1891 | HBL

|

Max-Schmeling-Halle |

| Berlin Recycling Volleys | Volleyball | 1991 | Bundesliga | Max-Schmeling-Halle |

| Berliner Hockey Club | Lacrosse | 2005 | Bundesliga | Ernst-Reuter-Feld |

See also

- List of fiction set in Berlin

- List of honorary citizens of Berlin

- List of people from Berlin

- List of songs about Berlin

References

Citations

- ^ "Nicknames For Berlin (Popular, Cute, Funny & Unique)". LetsLearnSlang.com. 14 May 2023. Archived from the original on 12 January 2024. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "Gilly & Schinkel and Athens on the Spree: Berlin Architecture 1790–1840 with Barry Bergdoll". Institute of Classical Architecture & Art. 1 September 2020. Archived from the original on 12 January 2024. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg (in German). Archived from the originalon 8 March 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg (in German). Archivedfrom the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ a b c citypopulation.de quoting Federal Statistics Office. "Germany: Urban Areas". Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ "Bevölkerungsanstieg in Berlin und Brandenburg mit nachlassender Dynamik" (PDF). statistik-berlin-brandenburg.de. Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg. 8 February 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ "Bruttoinlandsprodukt, Bruttowertschöpfung | Statistikportal.de". Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder | Gemeinsames Statistikportal (in German). Archived from the original on 25 September 2023. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ "Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by metropolitan regions". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ (/bɜːrˈlɪn/, bur-LIN; German: [bɛʁˈliːn] ⓘ)

- ^ ISBN 9783411040674.

- ^ Milbradt, Friederike (6 February 2019). "Deutschland: Die größten Städte" (in German). Die Zeit (Magazin). Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "75 329 mehr Berlinerinnen und Berliner als Ende 2021". www.statistik-berlin-brandenburg.de (in German). Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ "Einwohnerzahlen deutscher Metropolregionen 2022". Statista (in German). Archived from the original on 19 August 2023. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- ^ "Daten und Fakten zur Hauptstadtregion". www.berlin-brandenburg.de. 4 October 2016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ a b Senatsverwaltung für Umwelt, Verkehr und Klimaschutz Berlin, Referat Freiraumplanung und Stadtgrün. "Anteil öffentlicher Grünflächen in Berlin" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Niederlagsrecht" [Settlement rights] (in German). Verein für die Geschichte Berlins. August 2004. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ "Topographies of Class: Modern Architecture and Mass Society in Weimar Berlin (Social History, Popular Culture and Politics in Germany)". www.h-net.org. September 2009. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ^ "Berlin Wall". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 June 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ "ICCA publishes top 20 country and city rankings 2007". ICCA. Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ a b "Berlin City of Design" (Press release). UNESCO. 2005. Archived from the original on 16 August 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ "Berlin Beats Rome as Tourist Attraction as Hordes Descend". Bloomberg L.P. 4 September 2014. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ "Hollywood Helps Revive Berlin's Former Movie Glory". Deutsche Welle. 9 August 2008. Archived from the original on 13 August 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ a b c "World Heritage Site Museumsinsel". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ISBN 9783411062522.

- ^ "Die Geschichte Berlins: Zeittafel & Fakten". 11 May 2022. Archived from the original on 2 December 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Thomas Lackmann (4 January 2015). "Berliner Stadtmitte: Was aus den Fundamenten der mittelalterlichen Gerichtslaube wird" (in German). Tagesspiegel. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "Zitadelle Spandau". BerlinOnline Stadtportal GmbH & Co. KG. 2002. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ "The medieval trading center". BerlinOnline Stadtportal GmbH & Co. KG. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ a b Stöver B. Geschichte Berlins Verlag CH Beck 2010 ISBN 9783406600678

- ^ Komander, Gerhild H. M. (November 2004). "Berliner Unwillen" [Berlin unwillingness] (in German). Verein für die Geschichte Berlins e. V. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ "The electors' residence". BerlinOnline Stadtportal GmbH & Co. KG. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ "Berlin Cathedral". SMPProtein. Archived from the original on 18 August 2006. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ "Brandenburg during the 30 Years War". World History at KMLA. Archived from the original on 28 September 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas (1853). Fraser's Magazine. J. Fraser. p. 63. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-275-95196-2. Archivedfrom the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-74059-988-7. Archivedfrom the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-61069-248-9. Archivedfrom the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Horlemann, Bernd (Hrsg.), Mende, Hans-Jürgen (Hrsg.): Berlin 1994. Taschenkalender. Edition Luisenstadt Berlin, Nr. 01280.

- ISBN 978-971-23-1472-8. Archivedfrom the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-133-70864-3. Archivedfrom the original on 14 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-78023-069-6. Archivedfrom the original on 14 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-59880-914-5. Archivedfrom the original on 14 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-74220-407-9. Archivedfrom the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-3-406-65633-0. Archivedfrom the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-84545-416-6. Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-85828-682-2.

- ^ Francis, Matthew (3 March 2017). "How Albert Einstein Used His Fame to Denounce American Racism". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1921". Nobel Prize. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ISBN 9783936872934.

- ^ "The Jewish Community of Berlin". Holocaust Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ 1936 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 25 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Volume 1. pp. 141–9, 154–62. Accessed 17 October 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

- ^ "Lager für Sinti und Roma in Berlin-Marzahn". Bundesarchiv.de (in German). Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ISBN 9780786412044

- ^ Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Benz (27 April 2005). "Berlin – auf dem Weg zur geteilten Stadt" [Berlin – on the way to a divided city] (in German). Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Archived from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ "Berlin Airlift / Blockade". Western Allies Berlin. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ "Berlin after 1945". BerlinOnline Stadtportal GmbH & Co. KG. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-521-85824-3, pp. 125‒56, 223‒26.

- ^ "Ostpolitik: The Quadripartite Agreement of September 3, 1971". U.S. Diplomatic Mission to Germany. 1996. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ Berlin ‒ Washington, 1800‒2000: Capital Cities, Cultural Representation, and National Identities, ed. Andreas Daum and Christof Mauch. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006, 23‒27.

- ^ "AGI". AGI. Archived from the original on 21 August 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ "Berlin Mayoral Contest Has Many Uncertainties". The New York Times. 1 December 1990. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ Kinzer, Stephan (19 June 1994). "Allied Soldiers March to Say Farewell to Berlin". The New York Times. New York City. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ "When Did Germany's Capital Move to Berlin?". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ "Bezirke or Boroughs, Berlin, Germany, 2001 – Digital Maps and Geospatial Data | Princeton University". maps.princeton.edu. Archived from the original on 21 August 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ "Zidane off as Italy win World Cup". 9 July 2006. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ "IS reklamiert Attacke auf Weihnachtsmarkt für sich" [IS recalls attack on Christmas market for itself]. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). 20 December 2016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ "Berlin attack: First aider dies 5 years after Christmas market murders". BBC. 26 October 2021. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ "Protests against far-right politics draw thousands – DW – 10/13/2018". dw.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ Gardner, Nicky; Kries, Susanne (8 November 2020). "Berlin's Tegel airport: A love letter as it prepares to close". The Independent (in German). Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Jacobs, Stefan (29 January 2021). "BER schließt Terminal in Schönefeld am 23. Februar" [BER closes the terminal in Schönefeld on February 23]. Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "BVG will verlängerte U5 am 4. Dezember eröffnen" [BVG wants to open the extended U5 on December 4th]. rbb24 (in German). 24 August 2020. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Humboldt Forum will zunächst nur digital eröffnen" [Humboldt Forum will initially only open digitally]. Der Tagesspiegel (in German). 27 November 2020. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Completed Humboldt Forum opens in Berlin – DW – 09/16/2022". dw.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland [Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany] (Article 29) (in German). Parlamentarischer Rat. 24 May 1949. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland [Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany] (Einzelnorm 118a) (in German). Bundestag. 27 October 1994. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b "LÄNDERFUSION / FUSIONSVERTRAG (1995)". 2004. Archived from the original on 5 March 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Die Brandenburger wollen keine Berliner Verhältnisse". Tagesspiegel (in German). 4 May 2016. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Satellite Image Berlin". Google Maps. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ Triantafillou, Nikolaus (27 January 2015). "Berlin hat eine neue Spitze" [Berlin has a new top] (in German). Qiez. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Jacobs, Stefan (22 February 2015). "Der höchste Berg von Berlin ist neuerdings in Pankow" [The tallest mountain in Berlin is now in Pankow]. Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ "Berlin, Germany Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "Berlin, Germany Climate Summary". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ISBN 9781135835057. Archivedfrom the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ "weather.com". weather.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ "Climate figures". World Weather Information Service. Archived from the original on 17 August 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ "Temperaturmonatsmittel BERLIN-TEMPELHOF 1701- 1993". old.wetterzentrale.de. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "Niederschlagsmonatssummen BERLIN-DAHLEM 1848– 1990". old.wetterzentrale.de. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "Wetter und Klima – Deutscher Wetterdienst – CDC (Climate Data Center)". www.dwd.de. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- National Oceanic and Atmosphric Administration. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

WMO number: 10385

- ^ "Berlin (10381) – WMO Weather Station". NOAA. Retrieved 30 January 2019.[dead link] Archived 30 January 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Berliner Extremwerte". Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ "Alt- oder Neubau? So wohnt Berlin". Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "Berlin Modernism Housing Estates". Archived from the original on 28 February 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "Neumann: Stadtschloss wird teurer" [Neumann: Palace is getting more expensive]. Berliner Zeitung (in German). 24 June 2011. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ "Das Pathos der Berliner Republik" [The pathos of the Berlin republic]. Berliner Zeitung (in German). 19 May 2010. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ "Construction and redevelopment since 1990". Senate Department of Urban Development. Archived from the original on 10 June 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (9 May 2005). "A Forest of Pillars, Recalling the Unimaginable". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 August 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg (in German). pp. 4, 10, 13, 18–22. Archived(PDF) from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Population on 1 January by age groups and sex – functional urban areas, Eurostat Archived 3 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ "Initiativkreis Europäische Metropolregionen in Deutschland: Berlin-Brandenburg". www.deutsche-metropolregionen.org. 31 August 2020. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ statistics Berlin Brandenburg Archived 15 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. www.statistik-berlin-brandenburg.de Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ "How Berlin Became the World's Second Turkish..." Culture Trip. 6 March 2018. Archived from the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Dmitry Bulgakov (11 March 2001). "Berlin is speaking Russians' language". Russiajournal.com. Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ Heilwagen, Oliver (28 October 2001). "Berlin wird farbiger. Die Afrikaner kommen – Nachrichten Welt am Sonntag – Welt Online". Die Welt (in German). Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "Zweites Afrika-Magazin "Afrikanisches Viertel" erschienen Bezirksbürgermeister Dr. Christian Hanke ist Schirmherr" (Press release). Berlin: berlin.de. 6 February 2009. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ "Hummus in the Prenzlauer Berg". The Jewish Week. 12 December 2014. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ "457 000 Ausländer aus 190 Staaten in Berlin gemeldet" [457,000 Foreigners from 190 Countries Registered in Berlin]. Berliner Morgenpost (in German). 5 February 2011. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ "Fast jeder Dritte in Berlin hat einen Migrationshintergrund". www.rbb-online.de.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Von Andrea Dernbach (23 February 2009). "Migration: Berlin will illegalen Einwanderern helfen – Deutschland – Politik – Tagesspiegel". Der Tagesspiegel Online. Tagesspiegel.de. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ "Zahl der Ausländer in Berlin steigt auf Rekordhoch". Junge Freiheit (in German). 8 September 2016. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ "Berlin: Inside Europe's capital of Arab culture". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 27 October 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "Berlin to create 10,000 extra beds for Ukrainian refugees – DW – 11/20/2022". dw.com. Archived from the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "Survey of Ukrainian War Refugees". Federal Ministry of the Interior and Community. Archived from the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ISBN 9781108488099.

- ^ European Commission. "Official Languages". Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "how many- languages are spoken in berlin". Morgenpost.de. 18 May 2010. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Statistischer Bericht Einwohnerinnen und Einwohner im Land Berlin am 31 Dezember 2022 Archived 23 February 2021(Date mismatch) at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg (in German). pp. 6–7. Archived from the original(PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "Kirchenmitgliederzahlen am 31.12.2010" [Church membership on 31 December 2010] (PDF) (in German). Protestant Church in Germany. November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Die kleine Berlin–Statistik 2010" [The small Berlin statistic 2010] (PDF) (in German). Amt für Statistik Berlin–Brandenburg. December 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- ^ "Statistisches Jahrbuch für Berlin 2010" [Statistical yearbook for Berlin 2010] (PDF) (in German). Amt für Statistik Berlin–Brandenburg. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ Berger, Melanie (6 June 2016). "Ramadan in Flüchtlingsheimen und Schulen in Berlin". Der Tagesspiegel. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ Berger, Melanie (6 June 2016). "Ramadan in Flüchtlingsheimen und Schulen in Berlin" [Ramadan in refugee camps and schools in Berlin]. Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ Schupelius, Gunnar (28 May 2015). "Wird der Islam künftig die stärkste Religion in Berlin sein?". Berliner Zeitung. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ Ross, Mike (1 November 2014). "In Germany, a Jewish community now thrives". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ "Lutheran Diocese Berlin-Brandenburg". Selbständige Evangelisch-Lutherische Kirche. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "Berlin's mosques". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 11 November 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Keller, Claudia (10 November 2013). "Berlins jüdische Gotteshäuser vor der Pogromnacht 1938: Untergang einer religiösen Vielfalt" [Berlin's jewish places of worship before the Pogromnacht 1938: Decline of a religious diversity]. Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Archived from the original on 11 November 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

Von den weit mehr als 100 jüdischen Gotteshäusern sind gerade einmal zehn übrig geblieben. (in english: Of the far more than 100 synagogues, only ten are left.)

- ^ "Verfassung von Berlin – Abschnitt IV: Die Regierung". www.berlin.de (in German). 1 November 2016. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Berliner Haushalt Finanzsenator bleibt trotz sprudelnder Steuereinnahmen vorsichtig". Berliner Zeitung. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ "Vermögen" [Assets]. Berlin.de. 18 May 2017. Archived from the original on 28 September 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- Berlin.de (in German). 5 September 2019. Archivedfrom the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ "Real Estate Portal of the Berlin Business Location Center". Archived from the original on 10 December 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Berlin state election, 2006" (PDF). Der Landeswahlleiter für Berlin (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ "Kai Wegner zum Regierenden Bürgermeister von Berlin gewählt – neuer Senat im Amt". 27 April 2023. Archived from the original on 4 May 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ "Kai Wegner zum Regierenden Bürgermeister von Berlin gewählt – neuer Senat im Amt". Archived from the original on 4 May 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ Marsh, Sarah; Rinke, Andreas; Marsh, Sarah (27 April 2023). "Berlin gets first conservative mayor in more than two decades". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 August 2023. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "City Partnerships". Berlin.de. Governing Mayor of Berlin, Senate Chancellery, Directorate for Protocol and International Relations. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "Bundespräsident Horst Köhler" (in German). Bundespraesident.de. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ "Gesetz über die Feststellung des Bundeshaushaltsplans für das Haushaltsjahr 2014". buzer.de. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ "Der Regierungsumzug ist überfällig" (in German). Berliner Zeitung. 26 October 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "Germany – Embassies and Consulates". embassypages.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ "Berlin – Europe's New Start-Up Capital". Credit Suisse. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ "Berlin hat so wenig Arbeitslose wie seit 24 Jahren nicht". Berliner Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 3 December 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ "In Berlin gibt es so viele Beschäftigte wie nie zuvor". Berliner Zeitung (in German). 28 January 2015. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ "Poor but sexy". The Economist. 21 September 2006. Archived from the original on 22 June 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Die kleine Berlin Statistik" (PDF). berlin.de. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ "Immer mehr Konzerne suchen den Spirit Berlins". Berliner Morgenpost. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ "The Science and Technology Park Berlin-Adlershof". Berlin Adlershof: Facts and Figures. Adlershof. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ "Global Cities Investment Monitor 2012" (PDF). KPMG. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ "Arbeitslosenquote nach Bundesländern in Deutschland 2018 | Statista". Statista (in German). Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "Arbeitslosenquote in Berlin bis 2018". Statista. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ "Global 500 2023". Fortune. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ "Berlin's 'poor but sexy' appeal turning city into European Silicon Valley". The Guardian. 3 January 2014. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ Frost, Simon (28 August 2015). "Berlin outranks London in start-up investment". euractiv.com. Archived from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ "Global 500 2023". Fortune. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ "Berlin's Economy in Figures" (PDF). IHK Berlin. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ "DB Schenker to concentrate control functions in Frankfurt am Main". Archived from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ "A German Publisher Is Winning the Internet". Bloomberg.com. 7 August 2018. Archived from the original on 2 September 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ "Press – Facts and figures – BVR – National Association of German Cooperative Banks". Archived from the original on 8 January 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ "TOP 100 der deutschen Kreditwirtschaft" (PDF). die-bank.de (in German). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ "Bayer Worldwide: Activities and Directions to the German Sites". bayer.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Berlin Welcomes Record Numbers of Tourists and Convention Participants in 2014". visitBerlin. Archived from the original on 5 March 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ "Berlin No.1 city and Germany No.2 country in new ICCA rankings". C-MW.net. 12 January 2017. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ History Department at the University of San Diego. "Magnetic Recording History Pictures". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008.

- ^ "1935 AEG Magnetophon Tape Recorder". MIX. Penton Media Inc. 1 September 2006. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ Engel, Friedrich Karl; Peter Hammar (27 August 2006). "A Selected History of Magnetic Recording" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

A brief history of magnetic tape from the BASF Historian and the founding curator of the Ampex museum. - ^ "Manfred von Ardenne". Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ "Following the Followers of Fashion". Handelsblatt Global. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ "Berlin Cracks the Startup Code". Businessweek. 12 April 2012. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Culture and Creative Industries Index Berlin-Brandenburg 2015". Creative City Berlin. 7 June 2015. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ^ "Wall-to-wall culture". The Age. Australia. 10 November 2007. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- ^ "Media Companies in Berlin and Potsdam". medienboard. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "Quality of Living City Ranking | Mercer". mobilityexchange.mercer.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2019.