Cybernetics in the Soviet Union

Cybernetics in the Soviet Union had its own particular characteristics, as the study of

Initially, from 1950 to 1954, the reception of cybernetics by the Soviet Union establishment was exclusively negative. The Soviet

Under the formerly suppressive scientific culture of the Soviet Union, cybernetics began to serve as an umbrella term for previously maligned areas of Soviet science, such as structural linguistics and genetics. Under the leadership of academician Aksel Berg, the Council of Cybernetics was formed, an umbrella organization dedicated to providing funding for these new lights of Soviet science. By the 1960s, this fast legitimization put cybernetics in fashion, as "cybernetics" became a buzzword among career-minded scientists. Additionally, Berg's administration left many of the original cyberneticians of the organization disgruntled; complaints were made that he seemed more focused on administration than scientific research, citing Berg's grand plans to expand the council to subsume "practically all of Soviet science". By the 1980s, cybernetics had lost relevance in Soviet scientific culture, as its terminology and political function were succeeded by those of informatics in the Soviet Union and, eventually, post-Soviet states.

Official criticism: 1950–1954

Cybernetics: a reactionary pseudoscience that appeared in the U.S.A. after World War II and also spread through other capitalist countries. Cybernetics clearly reflects one of the basic features of the bourgeois worldview—its inhumanity, striving to transform workers into an extension of the machine, into a tool of production, and an instrument of war. At the same time, for cybernetics an imperialistic utopia is characteristic—replacing living, thinking man, fighting for his interests, by a machine, both in industry and in war. The instigators of a new world war use cybernetics in their dirty, practical affairs.

"Cybernetics" in the Short Philosophical Dictionary, 1954[2]

The initial reception of cybernetics in the

The first to latch onto Cybernetics was science journalist, Boris Agapov, following the post-war American interest in the developments in computer technology. The cover of the January 23, 1950, issue of Time had boasted an anthropomorphic cartoon of a Harvard Mark III under the slogan "Can Man Build a Superman?". On 4 May 1950, Agapov published an article in the Literaturnaya Gazeta entitled "Mark III, a Calculator", ridiculing this American excitement at the "sweet dream" of the military and industrial uses of these new "thinking machines", and criticizing cybernetics originator Norbert Wiener as an example of the "charlatans and obscurantists, whom capitalists substitute for genuine scientists".[4][5][6]

Though it was not commissioned by any Soviet authority and never mentioned the science by name, Agapov's article was taken as a signal of an official critical attitude towards cybernetics; editions of Wiener's

During this period, Stalin himself never engaged in this rabid criticism of cybernetics, with the head of the Soviet Department of Sciences, Iurii Zhdanov, recalling that "he never opposed cybernetics" and made every effort "to advance computer technology" in order to give the USSR the technological advantage.[15] Though the scale of this campaign was modest, with only around 10 anti-cybernetic publications being produced, Valery Shilov has argued it constituted a "strict directive to action" from the "central ideological organs", a universal declaration of cybernetics as a bourgeois pseudoscience to be criticized and destroyed.[14]

Few of these critics had any access to primary sources on cybernetics. Agapov's sources were limited to the January 1950 issue of Time; the institute's criticisms were based on the 1949 volume of

Legitimization and rise: 1954–1961

The reformed academic culture of the Soviet Union, after the death of Stalin and reforms of the Khrushchev era, allowed cybernetics to tear down its previous ideological criticisms and redeem itself in the public view. To Soviet scientists, cybernetics emerged as a possible vector of escape from the ideological traps of Stalinism, replacing it with the computational objectivity of cybernetics.[21][22][23]

Military computer scientist Anatoly Kitov recalled stumbling onto Cybernetics in the secret library of the Special Construction Bureau and realizing instantly that "cybernetics was not a bourgeois pseudo-science, as official publications considered it at the time, but the opposite—a serious, important science". He joined with the dissident mathematician Alexey Lyapunov, and, in 1952, presented a pro-cybernetic paper to Voprosy Filosofii, which the journal tacitly endorsed, though the Communist Party required that Lyapunov and Kitov present public lectures on cybernetics before its publication, with 121 seminars produced in total from 1954 until 55.[24][25][26]

A very different academic, the Soviet philosopher and former ideological watchdog Ernst Kolman, also joined this rehabilitation. In November 1954, Kolman presented a lecture at the Academy of Social Sciences, condemning this stifling of cybernetics to a shocked audience, who had expected a lecture rehearsing previous Stalinist criticisms, and marched down to the office of Voprosy Filosofii to have his lecture published.[27]

The beginning of a Soviet cybernetic movement was therefore first signalled by two articles, published together in the July–August 1955 volume of Voprosy Filosofii: "The Main Features of Cybernetics" by Sergei Sobolev, Alexey Lyapunov, and Anatoly Kitov, and "What is Cybernetics" by Ernst Kolman.[28] According to Benjamin Peters, these "two Soviet articles set the stage for the revolution of cybernetics in the Soviet Union".[17]

The first article—authored by three Soviet military scientists—attempted to present the tenets of cybernetics as a coherent scientific theory, retooling it for Soviet use; they purposely avoided any discussion of philosophy, and presented Wiener as an American anti-capitalist, in order to avoid any politically dangerous confrontation. They asserted cybernetics' main tenets as:

- information theory,

- the theory of automatic high-speed electronic calculating machines as a theory of self-organizing logical processes,

- the theory of automatic

In

With this, Soviet cybernetics began its journey towards legitimization. Academician Aksel Berg, at the time Deputy Minister of Defense, authored secret reports beleaguering the deficient state of information science in the USSR, pointing towards the suppression of cybernetics as the prime culprit. Party officials allowed a small Soviet delegation to be sent to the First International Congress on Cybernetics in June 1956, and they informed the Party of the extent to which USSR was "lagging behind the developed countries" in computer technology.[34] Unfavorable descriptions of cybernetics were removed from official literature, and in 1958, the first Russian translations of Wiener's Cybernetics and The Human Use of Human Beings were published.[35]

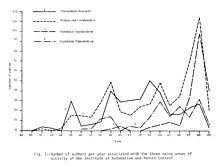

Alongside these translations, in 1958 the first Soviet journal on cybernetics, Проблемы кибернетики [Problems of Cybernetics], was launched with Lyapunov as its editor.[36] For the 1960 First International Federation of Automatic Control, Wiener came to Russia to lecture on cybernetics at the Polytechnic Museum. He arrived to see the booked hall swarmed with scientists eager to hear his lecture, some of whom sat on aisles and stairs to hear him speak; several Soviet publications, including the formerly anti-cybernetic Voprosy Filosofii, crammed in to get interviews from Wiener.[37] In the Krushchev Thaw, Soviet cybernetics had not only been legitimized as a science, but had entered the vogue in Soviet academia.[38][39]

On 10 April 1959, Berg sent a report edited by Lyapunov to a presidium of the

Thanks to Lyapunov, a further, 20-person Department of Cybernetics was created to solicit official funding for cybernetic research. Even with these institutions, Lyapunov still lamented that "the field of cybernetics in our country is not organized", and, from 1960 to 1961, worked with the department to establish an official Institute of Cybernetics. Lyapunov joined forces with the structural linguists, who had been authorized to create the Institute of Semiotics directed by Andrey Markov Jr., and, in June 1961, together planned to create an Institute of Cybernetics. Despite these efforts, Lyapunov lost faith in the project after Krushchev's refusal to build more Moscow scientific institutes, and the Institute never emerged, settling with the Council of Cybernetics instead gaining the formal powers of an institute, without any expansion of staff.[43]

Peak and decline: 1961–1980s

Berg continued with his campaign for Soviet cybernetics into the 1960s, as cybernetics entered the Soviet mainstream. Berg's council sponsored pro-cybernetic programs in Soviet media. 20-minute radio broadcasts, entitled "Cybernetics in Our Lives", were produced; a series of broadcasts on Moscow TV detailed advances in computer technology; and hundreds of lectures were given before various party members and workers on the subject of cybernetics. In 1961, the council produced an official volume proffering cybernetics as a socialist science: entitled Cybernetics—in the Service of Communism.[44]

The work of the council was rewarded when, at the

In July 1962, Berg created a plan for the radical restructuring of the Council such that it covered "practically all of Soviet science". This was met with cold reception from many of the researchers of the council, with one cybernetician complaining, in a letter to Lyapunov, that "[t]here are almost no results from the Council. Berg only demands paperwork and strives for the expansion of the Council." Lyapunov, disgruntled with Berg and the non-academic direction of cybernetics, refused to write for Cybernetics—in the Service of Communism and gradually lost his influence in cybernetics. As one memoirist put it, this resignation meant that "the center that had unified cybernetics disappeared, and cybernetics [would] naturally split into numerous branches."[49] While the old guard of cyberneticians complained, the cybernetics movement, as a whole, was exploding; with the council subsuming 170 projects and 29 institutions by 1962, and 500 projects and 150 institutions by 1967.[50]

According to Gerovitch, "by the early 1970s, the cybernetics movement [...] no longer challenged the orthodoxy; instead, tactical uses of cyberspeak overshadowed the original reformist goals that aspired the first Soviet cyberneticians."[51] The ideas which were once seen as controversial, and huddled under the umbrella organization of cybernetics, now entered the scientific mainstream, leaving cybernetics as a loose and incoherent ideological patchwork.[41] Some cyberneticians, whose dissident styles had been sheltered by the cybernetics movement, now felt persecuted, and some, such as Valentin Turchin, Alexander Lerner, and Igor Mel'čuk emigrated to escape this newfound scientific atmosphere.[52] By the 1980s, cybernetics had lost its cultural relevance, being replaced in Soviet scientific culture with the concepts of 'informatics'.[41]

Notable Soviet cyberneticists

- Aksel Berg (1893–1979) Deputy Minister of Defense of the Soviet Union (September 1953–November 1957)

- Yuri Gastev (1928–1993) dissident who emigrated in 1981

- Victor Glushkov (1923–1982) Soviet mathematician and founding father of Soviet cybernetics

- Anatoly Kitov (1920–2005)

- Andrey Kolmogorov (1903–1987)[53]

- Leonid Kraizmer (1912–2002)

- Alexey Lyapunov (1911–1973)

- Sergei Sobolev (1908–1989)

Notes

References

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Quoted in Peters 2012, p. 150. From Rosenthal, Mark M.; Iudin, Pavel F., eds. (1954). Kratkii filosofskii slovar [Short Philosophical Dictionary] (4th ed.). Moscow: Gospolitizdat. pp. 236–237.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, pp. 119–120.

- ^ a b Gerovitch 2002, pp. 120.

- ^ a b c Gerovitch 2015.

- ^ Peters 2012, p. 148–9.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, p. 121.

- ^ Shilov 2014, p. 181–182.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, p. 120–121.

- ^ Peters 2012, p. 149.

- ^ a b Gerovitch 2002, p. 125.

- ^ Holloway 1974, p. 299.

- ^ Peters 2012, pp. 149–150.

- ^ a b Shilov 2014, p. 179–180.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, p. 131.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, p. 126.

- ^ a b Peters 2008, p. 69.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, p. 127–131.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, p. 128–129.

- ^ Rindzeviciute 2010, p. 297.

- ^ Peters 2008, p. 71.

- ^ Peters 2012, pp. 151–154.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, pp. 153–155.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, pp. 173–177.

- ^ Peters 2012, pp. 154–156.

- ^ Rindzeviciute 2010, p. 301.

- ^ Peters 2012, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Peters 2012, p. 154.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, pp. 177–179.

- ^ Peters 2012, pp. 156–159.

- ^ Peters 2008, p. 72.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, pp. 170–173.

- ^ Peters 2012, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Gerovitch 2015, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Gerovitch 2015, pp. 196.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, pp. 193–197.

- ^ Fet 2014, pp. 194–195.

- ^ a b c Peters 2012, p. 164.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, p. 260.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, pp. 204–209.

- ^ a b c Peters 2012, p. 167.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, pp. 209–211.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, pp. 241–246.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, p. 255–6.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, p. 256.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, p. 260–1.

- ^ Peters 2012, p. 165.

- ^ Gerovitch 2009.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, p. 262–3.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, p. 262.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, p. 288.

- ^ Gerovitch 2002, p. 289–91.

- ISBN 0-394-44387-X.

Bibliography

- Бурас, Мария (2022). Лингвисты, пришедшие с холода. Moscow. OCLC 1293987701.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - Fet, Yakov (2014). Norbert Wiener in Moscow. 2014 Third International Conference on Computer Technology in Russia and in the Former Soviet Union. .

- Ford, John J. (1966). "Soviet Cybernetics and International Development". In Dechert, Charles R. (ed.). The Social Impact of Cybernetics. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Gerovitch, Slava (2002). From Newspeak to Cyberspeak: A History of Soviet Cybernetics. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. ISBN 9780262572255.

- Gerovitch, Slava (2009). "The Cybernetics Scare and the Origins of the Internet". Baltic Worlds. Vol. 2, no. 1. pp. 32–38. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Gerovitch, Slava (9 April 2015). "How the Computer Got Its Revenge on the Soviet Union". Nautilus. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Holloway, David (1974). "Innovation in Science—the Case of Cybernetics in the Soviet Union". Science Studies. 4 (4): 299–337. S2CID 143821328.

- Kapitonova, Yu. V.; Letichevskii, A. A. (2003). "A Scientist of the XXIst Century". Cybernetics and Systems Analysis. 39 (4): 471–476. S2CID 195221399.

- Leeds, Adam E. (2016). "Dreams in Cybernetic Fugue: Cold War Technoscience, the Intelligentsia, and the Birth of Soviet Mathematical Economics". Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences. 46 (5): 633–668. .

- Malinovsky, Boris Nikolaevich (2010). Pioneers of Soviet Computing (PDF). Translated by Aronie, Emmanuel (2nd ed.). SIGCIS. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Peters, Benjamin (2008). "Betrothal and Betrayal: The Soviet Translation of Norbert Wiener's Early Cybernetics". International Journal of Communication. 2: 66–80.

- Peters, Benjamin (2012). "Normalizing Soviet Cybernetics". Information & Culture. 47 (2): 145–175. S2CID 144363003.

- Peters, Benjamin (2016). How Not to Network a Nation: The Uneasy History of the Soviet Internet. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. ISBN 9780262034180.

- Rindzeviciute, Egle (2010). "Purification and Hybridisation of Soviet Cybernetics: The Politics of Scientific Governance in an Authoritarian Regime". Archiv für Sozialgeschichte. 50: 289–309.

- Shilov, Valery (2014). Reefs of Myths: Towards the History of Cybernetics in the Soviet Union. 2014 Third International Conference on Computer Technology in Russia and in the Former Soviet Union. ISBN 978-1-4799-1799-0.

External links

![]() Media related to Cybernetics at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cybernetics at Wikimedia Commons