Defensively equipped merchant ship

Defensively equipped merchant ship (DEMS) was an

Background

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, European countries such as

Anglo-German arms race

From the turn of the 20th century, growing tensions between Europe's

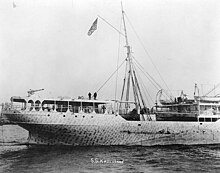

The Admiralty chose to do likewise, starting with the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company passenger liner RMS Aragon.[5] She was due to carry naval guns from December 1912, but within the British Government and Admiralty there was uncertainty as to how foreign countries and ports would react.[6] Many merchant ships had been armed in the 18th century and it had never been made illegal,[7] but Britain feared that foreign authorities might refuse to let armed British merchant ships enter port.[8] In January 1913 Rear Admiral Henry Campbell recommended that the Admiralty should send a merchant ship to sea with naval guns, but without ammunition, to test foreign governments' reaction.[6] A meeting chaired by Sir Francis Hopwood, Civil Lord of the Admiralty agreed to put guns without ammunition on a number of merchant ships "and see what happens." Sir Eyre Crowe was at the meeting and recorded "If nothing happens, it may be possible and easy, after a time, to place ammunition on board."[6]

In March the policy was made public, and in April it was implemented.[9] On 25 April 1913 Aragon left Southampton carrying two QF 4.7-inch (120 mm) naval guns on her stern.[7] The Admiralty planned to arm Houlder Brothers' La Correntina similarly if the reaction were favourable. Governments, newspapers and the public in South American countries that Aragon visited took little notice and expressed no concern.[9]

There was more criticism in Britain, where Commander Barry Domvile, Secretary to the Committee of Imperial Defence, warned that the policy undermined Britain's objection to the arming of German merchant ships. Domvile predicted that arming merchant ships would be ineffective, and would lead only to a second maritime arms race alongside the naval one. Gerard Noel, a former Admiral of the Fleet, told Churchill that were a merchant ship ever to fire its guns it could be accused of piracy. Churchill replied by drawing a distinction between merchant ships armed as auxiliary cruisers and those armed only for self-defence.[10]

Privately Churchill was more concerned, and in June 1913 he directed Admiralty staff to "do everything in our power to reconcile this new departure with the principles of international law".[10] However, the policy continued. Aragon's sister ship RMS Amazon was made the next DAMS, and in the following months further RMSP "A-liners" were armed.[7] They included the newly built Alcantara, that in the First World War did indeed serve as an armed merchant cruiser.

World War I

During the

The first merchant ship lost to U-boats was an 866-ton British steamer outbound from

The German Empire focused use of U-boats against merchant shipping in response to British blockade of German merchant shipping by declaring the entire North Sea a war zone on 2 November 1914. On 4 February 1915 Admiral Hugo von Pohl published a notice declaring a war zone in all waters around the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Within that zone, Germany was to conduct unrestricted submarine warfare against merchant ships from 18 February 1915, without warning and without regard to safety of their crew.[14]

In practice, U-boats still mostly conformed to earlier conventions of stopping ships when possible, and the first round of unrestricted submarine warfare was abandoned in September that year. The two procedures for sinking merchant ships were compared in 1915. Merchant ships escaped 42% of torpedo attacks made without warning, in comparison to 54% escaping from conventional surface attempts to stop the ship. However submarines can carry much more ammunition for the deck gun and thus can sink more ships. Guns aided escape,[15] though only a minimal number of submarines were sunk by gunfire from these ships.[16]

The number of civilian merchant ships armed with anti-submarine guns rose to 1,749 by September 1916 and 2,899 by February 1917.

World War II

Old naval guns had been stored since 1918 in ports for possible use. In the Second World War the objective was to equip each ship with a low-angle gun mounted aft as defence against surfaced submarines and a high-angle gun and rifle-calibre machine guns for defence against air attack.[20] 3,400 ships had been armed by the end of 1940;[12] and all ships were armed by 1943.[21]

The low-angle guns were typically in the 3-inch to 6-inch range (75–150 mm) depending on the size of the ship.

Untrained gunners posed significant risk to friendly aircraft in the absence of efficient communications.

D-day landings and the Royal Observer Corps

In 1944, during preparations for the invasion of France called Operation Overlord there was deep concern over the danger to Allied aircraft from the large number of DEMS involved in the landings. A request for volunteer aircraft recognition experts from the Royal Observer Corps produced 1,094 highly qualified candidates, from which 796 were selected to perform valuable aircraft recognition duties as seaborne volunteers.[25]

These Seaborne Observers were organised by Group Commandant C. G. Cooke and trained at the Royal Bath Hotel

The general impression amongst the Spitfire wings, covering our land and naval forces over and off the beach-head, appears to be that in the majority of cases the fire has come from warships and not from the merchant ships. Indeed I personally have yet to hear a single pilot report that a merchant vessel had opened fire on him

— Lucas

Twenty two seaborne observers survived their ships being sunk, two lost their lives and several more were injured during the landings. The "seaborne" operation was an unqualified success and in recognition,

I have read reports from both pilots and naval officers regarding the Seaborne volunteers on board merchant vessels during recent operations. All reports agree that the Seaborne volunteers have more than fulfilled their duties and have undoubtedly saved many of our aircraft from being engaged by our ships guns. I should be grateful if you would please convey to all ranks of the Royal Observer Corps, and in particular to the Seaborne observers themselves, how grateful I, and all pilots in the Allied Expeditionary Air Force, are for their assistance, which has contributed in no small measure to the safety of our own aircraft, and also to the efficient protection of the ships at sea. The work of the Royal Observer Corps is quite often unjustly overlooked, and receives little recognition, and I therefore wish that the service they rendered on this occasion be as widely advertised as possible, and all units of the Air Defence of Great Britain are therefore to be informed of the success of this latest venture of the Royal Observer Corps.

— Leigh-Mallory

As of 2010 there is a Seaborne Observers’ Association for the dwindling number of survivors. Air Vice-Marshal George Black (Rtd.), a former Commandant ROC, is the honorary president.

Japan

The Imperial Japanese Army established several shipping artillery units during World War II. These units provided detachments to protect Army-operated transports and chartered merchant ships from air or submarine attack. The Imperial Japanese Navy also formed air defence squads from April 1944 that were deployed on board ships.

United States

The

The United States followed the British practice of a single large gun aft. Early United States installations included low-angle

See also

- Armed merchantmen

- Commerce raiding

- East Indiaman

- Hired armed vessels

- Merchant raider

- STUFT - ships taken up from trade

- Q-ship

Footnotes

- ^ Hague 2000, p. VIII.

- ^ Seligmann 2012, p. 136.

- ^ Seligmann 2012, p. 137.

- ^ Seligmann 2012, p. 135.

- ^ Seligmann 2012, p. 139.

- ^ a b c Seligmann 2012, p. 141.

- ^ a b c Seligmann 2012, p. 132.

- ^ Seligmann 2012, p. 140.

- ^ a b Seligmann 2012, p. 144.

- ^ a b Seligmann 2012, p. 145.

- ^ Tarrant 1989, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d van der Vat 1988, p. 124

- ^ Tarrant 1989, p. 12.

- ^ Tarrant 1989, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Tarrant 1989, p. 22

- Q-ships (disguised armed vessels intended as offensive decoys) did sink around 12-15 U-boats, mostly in 1915. https://uboat.net/wwi/fates/losses.html

- ^ Tarrant 1989, p. 37.

- ^ Steffen, Dirk (2004). "The Holtzendorff Memorandum of 22 December 1916 and Germany's Declaration of Unrestricted U-boat Warfare". The Journal of Military History.

- ^ Potter & Nimitz 1960, p. 465.

- ^ a b Hague 2000, p. 101.

- ^ Middlebrook 1976, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Morison 1975, p. 301

- ^ Hague 2000, p. 102.

- ^ van der Vat 1988, pp. 138–9.

- ^ ROC Seaborne Ops

- ^ Morison 1975, pp. 296–7.

- ^ Morison 1975, p. 297.

- ^ Cressman 2000, p. 58.

- ^ Campbell 1985, pp. 143.

- ^ Babcock & Wilcox 1944, pp. 6–7.

References

- Babcock & Wilcox (April 1944). "Victory Ships". Marine Engineering and Shipping Review.

- Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War Two. ISBN 0-87021-459-4.

- Cressman, Robert J. (2000). The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II. Annapolis, MD: ISBN 1-55750-149-1.

- Hague, Arnold (2000). The Allied Convoy System 1939–1945. Annapolis, MD: ISBN 1-55750-019-3.

- ISBN 0-7139-0927-7.

- ISBN 0316583014.

- ISBN 9780137968701.

- Seligmann, Matthew S (2012). The Royal Navy and the German Threat 1901–1914: Admiralty Plans to Protect British Trade in a War Against Germany. London and Oxford: ISBN 978-0-19-957403-2.

- Tarrant, V.E. (1989). The U-Boat Offensive 1914–1945. New York: ISBN 1-85409-520-X.

- ISBN 0-06-015967-7.

Further reading

- Hughes, Terry; Costello, John (1977). The Battle of the Atlantic. New York: ISBN 0-385-27012-7.

- Marcus, Alex (1986). "DEMS? What's DEMS?": The Story of the Men of the Royal Australian Navy who manned Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships during World War II. Bowen Hills, Qld.: Boolarong Publications. ISBN 0-86439-012-2.

- Rohwer, J; Hummelchen, G (1992). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945. Annapolis, MD: ISBN 1-55750-105-X.

- Slader, John (2009). Fourth Service: Merchantmen at War, 1939–45. New York: Brick Tower Press. ISBN 978-1-899694-45-7.