Durham House, London

| Durham House | |

|---|---|

| Durham Inn | |

Durham House, 1806 engraving by John Thomas Smith | |

| Etymology | Bishop of Durham |

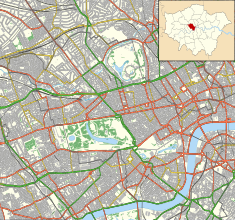

| Location | Strand, Westminster, London |

| Coordinates | 51°30′36″N 0°07′21″W / 51.5099847°N 0.1226087°W |

| Built | ≈1345 |

| Built for | Bishop Thomas Hatfield |

| Original use | Bishop's palace |

| Demolished | ≈1760 |

| Current use | Current location of the Adelphi Theatre |

| Architect | Anthony Bek |

| Architectural style(s) | Medieval |

Durham House, also known as Durham Inn, was the historic London town house of the Bishop of Durham in the Strand. Its gardens descended to the River Thames.

History

Origins

Bishop Thomas Hatfield built the opulent Durham House as a London residence in about 1345. It had a large chapel and a high-ceilinged great hall supported by marble pillars. On the Strand side its gatehouse led to a large courtyard. The hall and chapel faced the entrance, and private apartments overlooked the river.

Accounts describe Durham House as a noble palace befitting a prince. King Henry IV, his son Henry, Prince of Wales (later Henry V), and their retinues stayed once at the residence.

Tudor and Jacobean era

While Durham House remained an episcopal palace,

Mary's predecessor,

Upon her accession, Elizabeth seized possession of Durham House again, and deprived Tunstall of his see; she kept possession of the residence until 1583, when she granted it to

It was in Durham House that Raleigh hosted

Once safely delivered to England, the two Indians quickly made a sensation at the royal court. Raleigh's priority however was not publicity but rather intelligence about his new land of Virginia, and he restricted access to the exotic newcomers, assigning the scientist Thomas Harriot the job of deciphering and learning the Carolina Algonquian language,[6] using a phonetic alphabet of his own invention in order to effect the translation.

Upon Elizabeth's death and Raleigh's resultant loss of influence at court,

Decline

Neither Matthew nor any of his successors resided at Durham House and it became dilapidated as a result. The stables were demolished for construction of the New Exchange, a market which was occupied by milliners and seamstresses in shops along upper and lower tiers on each side of a central alley. In the 1630s it was the setting for the Durham House Group, including Richard Neile, William Laud and other high church Anglicans.[7][8]

The best portion of the house was tenanted by

The last portion of the ruins was cleared away early in the reign of King

See also

Other Strand mansions:

Notes

- ^ Williams 1971, p. 15.

- ^ Jones, Philippa, The other Tudors, pg. 80.

- ^ Gater, G.H.; Wheeler, E.P., eds. (1937). Survey of London: Volume 18, St Martin-in-The-Fields II: the Strand. London: London County Council. pp. 84–89. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ de Lisle 2008 pp. 93, 304; Ives 2009 p. 321

- ^ Milton, p.63

- ^ Milton, p.70

- ISBN 978-0-19-513886-3.

- ISBN 978-0-281-07605-5.

- ^ "Durham House". Royal Palaces | An Encyclopedia of British Royal Palaces and Royal Builders. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ISBN 9780300117295. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

Sources

- Durham House (LondonOnline)

- de Lisle, Leanda (2008): The Sisters Who Would Be Queen: Mary, Katherine and Lady Jane Grey. A Tudor Tragedy Ballantine Books ISBN 978-0-345-49135-0

- ISBN 978-1-4051-9413-6

Bibliography

- Borer, Mary Cathcart. The City of London: A History. (NY: McKay, 1977) (pp 157)

- Milton, Giles, Big Chief Elizabeth - How England's Adventurers Gambled and Won the New World, Hodder & Stoughton, London (2000)

- Stone, Lawrence. Family and Fortune: Studies in Aristocratic Finance in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1973) (pp 96–97, 100, 103)

- Stow, John A Survey of London. Reprinted from the Text of 1603. Ed. Charles Lethbridge Kingsford. 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1908) (2:400)

- Williams, Neville (1971). Henry VIII and His Court. Macmillan Pub Co. ISBN 978-0-02-629100-2