Edward FitzGerald (poet)

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (December 2022) |

Edward FitzGerald | |

|---|---|

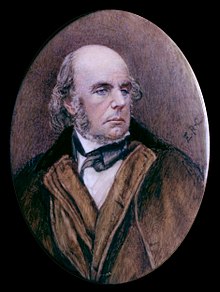

Portrait by Eva Rivett-Carnac (after a photograph of 1873) | |

| Born | 31 March 1809 Bredfield House, Bredfield, Woodbridge, Suffolk, England |

| Died | 14 June 1883 (aged 74) Merton, Norfolk, England |

| Occupation |

|

| Notable works | English translation of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam |

| Signature | |

Edward FitzGerald or Fitzgerald[a] (31 March 1809 – 14 June 1883) was an English poet and writer. His most famous poem is the first and best-known English translation of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which has kept its reputation and popularity since the 1860s.

Life

Edward FitzGerald was born Edward Purcell at Bredfield House in Bredfield, some two miles north of Woodbridge, Suffolk, England, in 1809. In 1818, his father, John Purcell, assumed the name and arms of his wife's family, the FitzGeralds.[1] His elder brother John used the surname Purcell-Fitzgerald from 1858.[2]

The change of family name occurred shortly after FitzGerald's mother inherited a second fortune. She had previously inherited over half a million pounds from an aunt, but in 1818, her father died and left her considerably more than that. The FitzGeralds were one of the wealthiest families in England. Edward FitzGerald later commented that all of his relatives were mad; further, that he was insane as well, but was at least aware of the fact.[3]

In 1816, the family moved to France, and lived in St Germain as well as Paris, but in 1818, after the death of his maternal grandfather, the family had to return to England. In 1821, Edward was sent to King Edward VI School, Bury St Edmunds. In 1826, he went on to Trinity College, Cambridge.[4] He became acquainted with William Makepeace Thackeray and William Hepworth Thompson.[1] Though he had many friends who were members of the Cambridge Apostles, most notably Alfred Tennyson, FitzGerald himself was never offered an invitation to this famous group.[citation needed] In 1830, FitzGerald left for Paris, but in 1831 was living in a farmhouse on the battlefield of Naseby.[1]

Needing no employment, FitzGerald moved to his native Suffolk, where he lived quietly, never leaving the county for more than a week or two while he resided there. Until 1835, the FitzGeralds lived in Wherstead, then moved until 1853 to a cottage in the grounds of Boulge Hall, near Woodbridge, to which his parents had moved. In 1860, he again moved with his family to Farlingay Hall, where they stayed until in 1873. Their final move was to Woodbridge itself, where FitzGerald resided at his own house close by, called Little Grange. During most of this time, FitzGerald was preoccupied with flowers, music and literature. Friends like Tennyson and Thackeray had surpassed him in the field of literature, and for a long time FitzGerald showed no intention of emulating their literary success. In 1851, he published his first book, Euphranor, a Platonic dialogue, born of memories of the old happy life in Cambridge. This was followed in 1852 by the publication of Polonius, a collection of "saws and modern instances," some of them his own, the rest borrowed from the less familiar English classics. FitzGerald began the study of Spanish poetry in 1850 at Elmsett, followed by Persian literature at the University of Oxford with Professor Edward Byles Cowell in 1853.[1]

FitzGerald married Lucy, daughter of the

Early literary work

In 1853, FitzGerald issued Six Dramas of Calderon, freely translated.

However, it was discovered in 1861 by Rossetti and soon after by Swinburne and Lord Houghton. The Rubaiyat slowly became famous, but it was not until 1868 that FitzGerald was encouraged to print a second, greatly revised edition of it. He had produced in 1865 a version of the Agamemnon, and two more plays from Calderón. In 1880–1881, he privately issued translations of the two Oedipus tragedies. His last publication was Readings in Crabbe, 1882. He left in manuscript a version of Attar of Nishapur's Mantic-Uttair.[1] This last translation FitzGerald called "A Bird's-Eye view of the Bird Parliament", whittling the Persian original (some 4500 lines) down to a more manageable 1500 lines in English. Some have called this translation a virtually unknown masterpiece.[7]

From 1861 onwards, FitzGerald's greatest interest had been in the sea. In June 1863 he bought a yacht, "The Scandal", and in 1867 he became part-owner of a herring lugger, the Meum and Tuum ("mine and thine"). For some years up to 1871, he spent his summers "knocking about somewhere outside of Lowestoft." He died in his sleep in 1883 and was buried in the graveyard at St Michael's Church in Boulge, Suffolk. He was in his own words "an idle fellow, but one whose friendships were more like loves." In 1885 his fame was enhanced by Tennyson's dedication of his Tiresias to FitzGerald's memory, in some reminiscent verses to "Old Fitz."[1]

Personal life

FitzGerald was unobtrusive in person, but during the 1890s, his individuality gradually gained a broad influence in English belles-lettres.[8] Little was known of FitzGerald's character until W. Aldis Wright published his three-volume Letters and Literary Remains in 1889 and the Letters to Fanny Kemble in 1895. These letters reveal FitzGerald as a witty and sympathetic letter writer.[9] George Gissing found them interesting enough to read the three-volume collection twice, in 1890 and 1896.[10]

FitzGerald's emotional life was complex. He was close to many friends, among them William Kenworthy Browne, who was 16 when they met, and who died in a horse-riding accident in 1859.[11] His loss was very difficult for FitzGerald. Later, FitzGerald became close to a fisherman named Joseph Fletcher, with whom he had bought a herring boat.[5] While it appears there are no contemporary sources on the matter, a number of present-day academics and journalists believe FitzGerald to have been a homosexual.[12] With Professor Daniel Karlin writing in his introduction to the 2009 edition of Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám that "His [FitzGerald] homoerotic feelings (...) were probably unclear to him, at least in the form conveyed by our word 'gay'",[13] it is unclear whether FitzGerald himself ever identified himself as a homosexual or acknowledged himself to be one.

FitzGerald grew disenchanted with Christianity and eventually ceased to attend church.[14] This drew the attention of the local pastor, who stopped by. FitzGerald reportedly told him that his decision to absent himself was the fruit of long and hard meditation. When the pastor protested, FitzGerald showed him the door and said, "Sir, you might have conceived that a man does not come to my years of life without thinking much of these things. I believe I may say that I have reflected [on] them fully as much as yourself. You need not repeat this visit."[14]

The 1908 book Edward Fitzgerald and "Posh": Herring Merchants (Including letters from E. Fitzgerald to J. Fletcher) recounts the friendship of Fitzgerald with Joseph Fletcher (born June 1838), nicknamed "Posh", who was still living when James Blyth started researching for the book.[15] Posh is also often present in Fitzgerald's letters. Documentary data about the Fitzgerald–Posh partnership are available at the Port of Lowestoft Research Society. Posh died at Mutford Union workhouse, near Lowestoft, on 7 September 1915, at the age of 76.[16]

Fitzgerald was termed "almost vegetarian", as he ate meat only in other people's houses.[17] His biographer Thomas Wright noted that "though never a strict vegetarian, his diet was mainly bread and fruit."[18] Several years before his death, FitzGerald said of his diet, "Tea, pure and simple, with bread-and-butter, is the only meal I do care to join in."[19]

Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam

Beginning in 1859, FitzGerald authorized four editions (1859, 1868, 1872 and 1879) and there was a fifth posthumous edition (1889) of his translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám (Persian: رباعیات عمر خیام). Three (the first, second, and fifth) differ significantly; the second and third are almost identical, as are the fourth and fifth. The first and fifth are reprinted almost equally often,[20][21] and equally often anthologized.[22]

A Book of Verses underneath the Bough,

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread – and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness –

Oh, Wilderness were Paradise enow!

Stanza XI above, from the fifth edition, differs from the corresponding stanza in the first edition, wherein it reads: "Here with a Loaf of Bread beneath the bough/A Flask of Wine, a Book of Verse – and Thou". Other differences are discernible. Stanza XLIX is more well known in its incarnation in the first edition (1859):

'Tis all a Chequer-board of Nights and Days

Where Destiny with Men for Pieces plays:

Hither and thither moves, and mates, and slays,

And one by one back in the Closet lays.

The fifth edition (1889) of stanza LXIX, with different numbering, is less familiar: "But helpless Pieces of the Game He plays/Upon this Chequer-board of Nights and Days;/Hither and thither moves, and checks, and slays,/And one by one back in the Closet lays."

FitzGerald's translation of the Rubáiyát is notable for being a work to which allusions are both frequent and ubiquitous.[8] It remains popular, but enjoyed its greatest popularity for a century following its publication, wherein it formed part of the wider English literary canon.[8]

One indicator of the popular status of the Rubáiyát is that, of the 101 stanzas in the poem's fifth edition, the

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on; nor all your Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all your Tears wash out a Word of it.

Lines and phrases from the poem have been used as the titles of many literary works, among them

Parodies

FitzGerald's translations were popular in the century of their publication, also with humorists for the purpose of parody.[8]

- The Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam by J. L. Duff utilises the original to create a satire commenting on Prohibition.

- Rubaiyat of a Persian Kitten by Oliver Herford, published in 1904, is the illustrated story of a kitten in parody of the original verses.

- The Rubaiyat of Omar Cayenne by Gelett Burgess (1866–1951) was a condemnation of the writing and publishing business.

- The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Jr. (1971) by Persia to Borneo.

- Astrophysicist general theory of relativityby observing a solar eclipse.

- The new Rubaiyat: Omar Khayyam reincarnated by "Ame Perdue" (pen name of W. J. Carroll) was published in Melbourne in 1943. It revisits the plaints of the original text with references to modern science, technology and industry.

See also

Notes

- ^ His name is seen written as both FitzGerald and Fitzgerald. The use here of FitzGerald conforms to that of his own publications, anthologies such as Quiller-Couch's Oxford Book of English Verse, and most reference books until about the 1960s.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gosse, Edmund (1911). "FitzGerald, Edward". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 443.

- ^ "Fitzgerald (formerly Purcell), John (FTST820J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ISBN 0-7100-0957-7.

- ^ "Edward Fitzgerald (FTST826E)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ a b c "Edward Fitzgerald", Poem Hunter

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1284168)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Briggs, A. D. P. (1998). The Rubaiyat and the Bird Parliament. Everyman's Poetry.

- ^ a b c d Staff (10 April 1909) "Two Centenaries" New York Times: Saturday Review of Books p. BR-220

- ISBN 0-8103-1710-9

- ^ Pierre Coustillas, ed., London and the Life of Literature in Late Victorian England: the Diary of George Gissing, Novelist. Brighton: Harvester Press, 1978, pp. 232, 396, 413 and 415.

- ISBN 978-1-5128-1413-2.

- ^ "From Persia to Tyneside and the door of darkness". The Independent. 5 November 1995. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- OCLC 320958676.

- ^ ISBN 0-87923-248-X.

- ^ Blyth, James (1908). Edward Fitzgerald and 'Posh', 'herring merchants' Including letters from E. Fitzgerald to J. Fletcher.

- ISBN 9781400854011.

- ^ "An Old Man in a Dry Month": a Brief Life of Edward FitzGerald (1809–1883)". The Victorian Web.

- ^ Thomas Wright, The Life of Edward Fitzgerald. New York, 1904, p. 116.

- ^ John Glyde, 1900 The Life of Edward Fitz-Gerald, by John Glyde. Chicago. p. 44.

- ISBN 0-8139-1689-5

- ISBN 0-486-26467-X

- Harper & Brothers, New York, vol. 2, 1926, p. 685, OCLC 1743706 Worldcat.org.

- ISBN 1-59308-042-5

Bibliography, biographies

- Euphranor. A Dialogue on Youth (William Pickering, 1851).

- The Works of Edward FitzGerald appeared in 1887.

- See also a chronological list of FitzGerald's works (Caxton Club, Chicago, 1899).

- Notes for a bibliography by Col. W. F. Prideaux, in Notes and Queries (9th series, vol. VL), published separately in 1901

- Letters and Literary Remains, ed. W. Aldis Wright, 1902–1903

- 'Letters to Fanny Kemble', ed. William Aldis Wright

- Life of Edward FitzGerald, by Thomas Wright (1904) contains a bibliography, vol. ii. pp. 241–243, and a list of sources, vol. i. pp. xvi–xvii

- The volume on FitzGerald in the "English Men of Letters" series is by A. C. Benson.

- The FitzGerald centenary was marked in March 1909. See the Centenary Celebrations Souvenir (Ipswich, 1909) and The Times for 25 March 1909.

- Today, the major source is Robert Bernard Martin's biography, With Friends Possessed: A Life of Edward Fitzgerald.

- A comprehensive four-volume collection of The Letters of Edward FitzGerald, edited by Syracuse University English professor Alfred M. Terhune and Annabelle Burdick Terhune, was published in 1980.

Further reading

- William Axon, "Omar" Fitzgerald. Good Health 46 (1), 1911, pp. 107–113

- Harold Bloom, Modern Critical Interpretations Philadelphia, 2004

- ISBN 0-14-029011-7

- Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, Victorian Afterlives: The Shaping of Influence in Nineteenth-Century Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002

- Garnett, Richard; Gosse, Edmund (1904). English Literature. Vol. 4. New York: Grosset & Dunlap.

- Francis Hindes Groome; Edward FitzGerald (1902). Edward FitzGerald. Portland, Maine: Thomas B. Mosher.

Edward FitzGerald

- Gary Sloan, Great Minds, "The Rubáiyát of Edward FitzOmar", Free Inquiry, Winter 2002/2003 – Volume 23, No. 1

External links

- Works by Edward FitzGerald at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Edward Fitzgerald (translator) at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Edward FitzGerald at Internet Archive

- Works by Edward FitzGerald at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Encyclopedia Iranica, "Fitzgerald Edward" by Dick Davis

- Bird Parliament by Edward FitzGerald

- Parodies of the Rubaiyat – several parodies of the Rubaiyat are included, with artwork and comparisons to the Fitzgerald translation.

- Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam. Rendered into English verse by Edward Fitzgerald. Complete edition showing variants in the five original printings. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1921

- Edward FitzGerald Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.