First Upper Peru campaign

| First Upper Peru campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Argentine War of Independence | |||||||

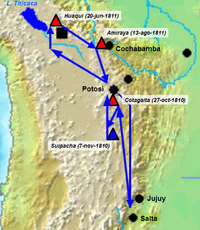

Path of the Military campaign. The blue mark is for patriot victories (Suipacha), the red mark for royalist victories (Cotagaita, Huaqui and Amiraya) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Patriots |

Royalists | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Antonio González Balcarce Juan José Viamonte | |||||||

The First Upper Peru campaign was a military campaign of the Argentine War of Independence, which took place in 1810. It was headed by Juan José Castelli, and attempted to expand the influence of the Buenos Aires May Revolution in Upper Peru (modern Bolivia). There were initial victories, such as in the Battle of Suipacha and the revolt of Cochabamba, but it was finally defeated during the Battle of Huaqui that returned Upper Peru to Royalist influence. Manuel Belgrano and José Rondeau would attempt other similarly ill-fated campaigns; the Royalists in the Upper Peru would be finally defeated by Sucre, whose military campaign came from the North supporting Simón Bolívar.

Antecedents

The Spanish king

Before proceeding to Upper Peru, this military campaign defeated a

Development

Castelli was not received well in Córdoba, where Liniers was popular, but he was in San Miguel de Tucumán. In Salta, despite the formal good reception, he had difficulty obtaining troops, mules, food, money or guns. He took the political leadership of the Expedition, displacing Hipólito Vieytes, and replaced Ocampo with Colonel Antonio González Balcarce. He was informed that Cochabamba revolted in support of the Junta, but was threatened by royalist forces from La Paz. Castelli intercepted as well a mail from Nieto to Gutiérrez de la Concha, governor of Córdoba, which was already executed for his support to Liniers. This mail mentioned a royalist army led by Goyeneche advancing over Jujuy. Balcarce, who had advanced to Potosi, was defeated by Nieto in the Battle of Cotagaita, so Castelli sent two hundred men and two cannons to strengthen his forces. With these reinforcements Balcarce achieved the victory at the Battle of Suipacha,[4] which allowed patriots to control all of Upper Peru unopposed. One of the men sent was Martín Miguel de Güemes, who would eventually lead the Guerra Gaucha in Salta years later.

At Villa Imperial, one of the richest cities of Upper Peru, an

He set up his government in

In November 1810 he sent a plan to the Junta: to cross the

In December, fifty-three peninsulars were banished to Salta, and the decision was delivered for approval of the Junta. The vocal Domingo Matheu, who was associated with Tulla and Pedro Salvador Casas, arranged the annulment of the act, arguing that Castelli had acted influenced by slander and unfounded accusations.[9] Support for Castelli began to decline, mainly due to the favourable treatment of natives and the determined opposition of the church, which attacked Castelli through his secretary Bernardo Monteagudo and his public atheism. Both royalists in Lima and Saavedra in Buenos Aires compared them both with Maximilien Robespierre, leader of the Reign of Terror of the French Revolution.

Castelli also abolished the

Defeat

The order of the Junta not to proceed to the Viceroyalty of Peru was a de facto truce that would last while not attacking Goyeneche. Castelli tried to turn the situation into a formal agreement, which would imply recognition of the Junta as a legitimate interlocutor. Goyeneche agreed to sign an armistice for 40 days until Lima was issued, and used that time to be strengthened. On 19 June, with the truce still in effect, an advanced royalist troop attacked positions at Juraicoragua. Castelli declared the truce broken and declared war on Peru.[13]

The royalist army crossed the Desaguadero on June 20, 1811, starting the Battle of Huaqui. The Army waited near Huaqui, between the plains of Azapanal and Lake Titicaca. The patriotic left wing, commanded by Diaz Velez, faced the bulk of the royalist forces, while the center was hit by the soldiers of Pio Tristan. Many patriotic soldiers recruited at the Upper Peru surrendered or fled, and many of the recruits in La Paz switched sides during the battle. The Saavedrist Juan José Viamonte was instrumental in the defeat, by refusing to join the conflict.[14]

Although the casualties of the Army of the North were not substantial, it was left demoralized and disbanded. The inhabitants of Upper Peru left them and welcomed the royalists back, so the army had to quickly leave those provinces. However, the resistance of Cochabamba prevented the royalists from proceeding to Buenos Aires.[15] Castelli moved to the post of Quirbe, and received orders to return to Buenos Aires for trial. However, upon learning of such orders they had already been replaced by others: Castelli should be confined at Catamarca, while Saavedra himself took charge of the Army of the North. Saavedra was deposed as soon as he left Buenos Aires, and confined in San Juan. The First Triumvirate, who took government by then, required Castelli to return.

Once in Buenos Aires, Castelli was in a situation of political isolation. The triumvirate and the newspaper La Gazeta accused him of defeat in Huaqui and seek punishment as deterrent. His former supporters were divided between those who joined the ideas of the Triumvirate and those no longer able to do much. Castelli suffered from tongue cancer during the long trial, which made him progressively difficult to speak, and died on October, 1812, with the trial still open.[16]

See also

Bibliography

- ISBN 950-49-0656-7.

- ISBN 950-581-799-1.

- ISBN 978-950-04-3258-0.

References

- ^ Galasso, p, 17

- ^ Galasso, p. 16-24

- ^ National..., p. 113

- ^ National..., p. 76

- ^ a b Galasso, p. 110

- ^ National..., p. 334

- ^ Galasso, p. 78-80

- ^ Galasso, p. 86-87

- ^ Galasso, p. 118

- ^ a b Galasso, p. 80

- ^ Galasso, p. 110-111

- ^ a b Galasso, p. 128

- ^ National..., p. 209-210

- ^ Galasso, p. 128-129

- ^ National..., p. 210

- ^ National... p. 114