François Pierre Joseph Amey

François Pierre Joseph Amey | |

|---|---|

| Born | 2 October 1768 General of Division |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | Baron of the Empire , 1810Mayor of Sélestat, 1820–30 |

François Pierre Joseph Amey (2 October 1768 – 16 November 1850) became a French division commander during the

where he was wounded.Sent to Spain in 1808 in command of German troops, Amey fought at the

Revolution

Amey was born in

Louis Marie Turreau took over the direction of the conflict on 30 December. Turreau started a campaign of savage repression against the Vendeans by "infernal columns" on 24 January 1794. The columns roamed the countryside burning farms and killing any rebels they caught, including in many cases, women and children. Instead of ending the revolt, the severity of the repression provoked a fresh uprising. The heavy hand of the undisciplined Republican armies sometimes fell on those citizens who were loyal and, for this, the government suspended Turreau on 13 May.[5] During the operation Amey commanded a garrison at Les Herbiers.[6] According to one account his troops were guilty of some of the worst excesses.[7] He was suspended for a month beginning in August 1794.[3] Few generals who served in the Vendée during the first half of 1794 had successful careers; Amey and Georges Joseph Dufour became the exceptions.[7]

After his suspension, Amey served in the

Empire

Amey was put in command of the

On 19 March 1808, Napoleon named Amey a

He transferred to

With a Prussian corps under

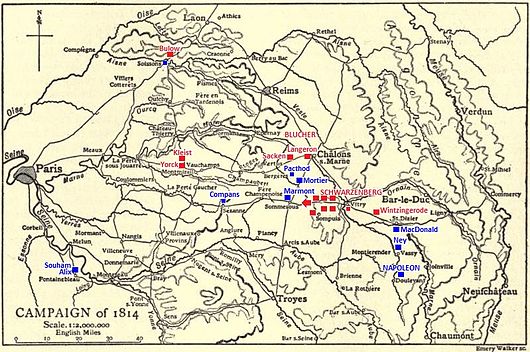

While Napoleon defeated

Schwarzenberg's 100,000-strong army defeated Napoleon's 30,000 troops at the

In the

When the badly beaten troops under Marmont and Mortier heard the approaching gunfire from Pacthod's fight, they believed that Napoleon was coming to save them. Though it was not true, this allowed the two marshals to rally their defeated troops. The Allies turned their attention away from the two marshals and focused on the destruction of Pacthod's command. This probably saved Marmont and Mortier from total disaster.[34] At the end, 78 guns were blasting Pacthod's soldiers and the Allied cavalry finally broke all the French infantry squares.[35] With his troops still in a single square, Amey tried to get away into the Saint-Gond Marshes, but only a small handful of men escaped being killed, wounded or taken prisoner.[36] Pacthod, Amey and several brigadiers were captured and the czar released them on parole in recognition of their bravery.[35]

Restoration

Under the

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Kubler 1982.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mullié 1852.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Jensen 2003.

- ^ Broughton 2006.

- ^ Phipps 2011, pp. 31–34.

- ^ Clénet 1993, p. 152.

- ^ a b Couteau-Bégarie & Doré-Graslin 2010, pp. 480–486.

- ^ Chandler 2005, p. 237.

- ^ Smith 1998, p. 224.

- ^ Smith 1998, pp. 241–243.

- ^ Smith 1998, p. 337.

- ^ Oman 1996, p. 525.

- ^ Oman 1996, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Nafziger 1993.

- ^ Leggiere 2007, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Leggiere 2007, pp. 149–152.

- ^ Leggiere 2007, pp. 153–156.

- ^ Petre 1994, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Smith 1998, p. 498.

- ^ Nafziger 2015, p. 193.

- ^ Nafziger 2015, pp. 617–618.

- ^ Nafziger 2015, p. 289.

- ^ Nafziger 2015, p. 629.

- ^ Smith 1998, pp. 512–513.

- ^ Petre 1994, p. 172.

- ^ Petre 1994, p. 176.

- ^ Petre 1994, p. 181.

- ^ Petre 1994, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Nafziger 2015, p. 335.

- ^ Smith 1998, pp. 513–515.

- ^ Nafziger 2015, p. 414.

- ^ a b Petre 1994, p. 191.

- ^ Nafziger 2015, p. 411.

- ^ Nafziger 2015, pp. 409–410.

- ^ a b Nafziger 2015, p. 413.

- ^ Petre 1994, p. 192.

References

- Broughton, Tony (2006). "Generals Who Served in the French Army during the Period 1789-1815: Abbatucci to Azemar". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ISBN 0-275-98612-8.

- Clénet, Louis-Marie (1993). Les colonnes infernales (in French). Perrin collection Vérités et Légendes.

- Couteau-Bégarie, Hervé; Doré-Graslin, Charles (2010). Histoire militaire des guerres de Vendée (in French). Economica.

- Jensen, Nathan D. (2003). "François-Pierre-Joseph Amey". FrenchEmpire.net. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Kubler, Maurice (1982). "AMEY François Pierre Joseph". Nouveau Dictionnaire de Biographie Alsacienne (in French). Fédération des Sociétés d'Histoire et d'Archéologie d'Alsace. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Leggiere, Michael V. (2007). The Fall of Napoleon: The Allied Invasion of France 1813-1814. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87542-4.

- Mullié, Charles (1852). Biographie des célébrités militaires des armées de terre et de mer de 1789 a 1850 (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Nafziger, George (1993). "French Grande Armée, 1 August 1812" (PDF). United States Army Combined Arms Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-909982-96-3.

- ISBN 1-85367-223-8.

- ISBN 1-85367-163-0.

- ISBN 978-1-908692-26-9.

- ISBN 1-85367-276-9.