HMS St Vincent (1908)

St Vincent at the Coronation Review, Spithead, 24 June 1911

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | St Vincent |

| Namesake | John Jervis, Earl of St Vincent |

| Ordered | 26 October 1907 |

| Builder | HM Dockyard, Portsmouth |

| Laid down | 30 December 1907 |

| Launched | 10 September 1908 |

| Completed | May 1909 |

| Commissioned | 3 May 1910 |

| Decommissioned | March 1921 |

| Identification | Pennant number: 16 (1914); 7A (Jan 18);[1] 85 (Apr 18); 24 (Nov 19); N.51 (Jan 22)[2] |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, 1 December 1921 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type | dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | 19,700 long tons (20,000 t) (normal) |

| Length | 536 ft (163.4 m) (o/a) |

| Beam | 84 ft (25.6 m) |

| Draught | 28 ft (8.5 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 × shafts; 2 × steam turbine sets |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 6,900 nmi (12,800 km; 7,900 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 756–835 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

HMS St Vincent was the

Design and description

The design of the St Vincent class was derived from that of the previous

St Vincent was powered by two sets of

Armament and armour

The St Vincent class was equipped with ten

The St Vincent-class ships were protected by a

Modifications

The guns on the forward turret roof were removed in 1911–1912 and the upper forward pair of guns in the superstructure were removed in 1913–1914. In addition,

Approximately 50 long tons (51 t) of additional deck armour was added after the Battle of Jutland. By April 1917, St Vincent mounted 13 four-inch anti-torpedo boat guns as well as one four-inch and one three-inch AA gun, and the ship was modified to operate a

Construction and career

St Vincent, named after

World War I

Between 17 and 20 July 1914, St Vincent took part in a test

Jellicoe's ships, including St Vincent, conducted gunnery drills on 10–13 January 1915 west of the Orkney and Shetland Islands. On the evening of 23 January, the bulk of the Grand Fleet sailed in support of Beatty's battlecruisers, but the fleet was too far away to participate in the Battle of Dogger Bank the following day. On 7–10 March, the Grand Fleet conducted a sweep in the northern North Sea, during which it conducted training manoeuvres. Another such cruise took place on 16–19 March. On 11 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a patrol in the central North Sea and returned to port on 14 April; another patrol in the area took place on 17–19 April, followed by gunnery drills off Shetland on 20–21 April.[18]

The Grand Fleet conducted sweeps into the central North Sea on 17–19 May and 29–31 May without encountering any German vessels. During 11–14 June the fleet conducted gunnery practice and battle exercises west of Shetland.[19] King George V inspected all of the personnel of the 2nd Division aboard St Vincent during his visit to Scapa on 8 July[12] and the Grand Fleet conducted training off Shetland beginning three days later. On 2–5 September, the fleet went on another cruise in the northern end of the North Sea and conducted gunnery drills. Throughout the rest of the month, the Grand Fleet conducted numerous training exercises. The ship, together with the majority of the Grand Fleet, conducted another sweep into the North Sea from 13 to 15 October. Almost three weeks later, St Vincent participated in another fleet training operation west of Orkney during 2–5 November.[20] She became a private ship that month when she was relieved by Colossus as flagship.[12]

The fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February 1916; Jellicoe had intended to use the

Battle of Jutland

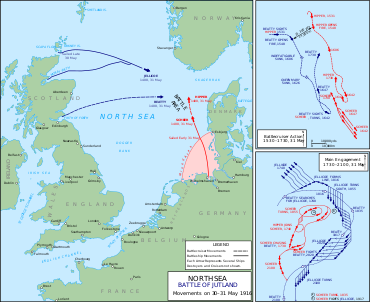

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet, composed of 16 dreadnoughts, 6 pre-dreadnoughts, and supporting ships, departed the Jade Bight early on the morning of 31 May. The fleet sailed in concert with Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper's 5 battlecruisers. The Royal Navy's Room 40 had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. In response the Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet, totalling some 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers, to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.[22] St Vincent, under the command of Captain William Fisher, was assigned to the 5th Division of the 1st Battle Squadron at this time. Shortly after 14:20,[Note 2] Fisher semaphored the Grand Fleet's flagship, Iron Duke, that his ship was monitoring strong radio signals on the frequency used by the High Seas Fleet that implied the Germans were nearby. Detection of further signals was communicated at 14:52.[23]

As the Grand Fleet began deploying from columns into a

Subsequent activity

After the battle, the ship was transferred to the

On 24 April 1918, St Vincent was under repair at Invergordon, Scotland, when she and the dreadnought Hercules were ordered north to reinforce the forces based at Scapa Flow and Orkney when the High Seas Fleet sortied north for the last time to intercept a convoy to Norway. She was unable to leave port before the Germans turned back after Moltke suffered engine damage.[26] The ship was present at Rosyth when the German fleet surrendered on 21 November. In March 1919, she was reduced to reserve and became a gunnery training ship at Portsmouth. St Vincent then became flagship of the Reserve Fleet in June and was relieved as gunnery training ship in December when she was transferred to Rosyth. There she remained until listed for disposal in March 1921 as obsolete. She was sold to the Stanlee Shipbreaking & Salvage Co. for scrap on 1 December 1921 and towed to Dover for demolition in March 1922.[12]

Notes

- quick-firing QF Mark III guns. In addition, he lists a 12-pounder (three-inch (76 mm)) gun.[5] Preston concurs on the number of 4 inchers, but does not list the 12 pounder.[4] Parkes says twenty 4-inch guns; while not identifying the type, he does say that they were 50-calibre guns[7] and Preston agrees.[8] Friedman shows the QF Mark III as a 40-calibre gun and states that the 50-calibre BL Mark VII gun armed all of the early dreadnoughts.[9]

- ^ The times used in this section are in UT, which is one hour behind CET, which is often used in German works.

Footnotes

- ^ Colledge, J J (1972). British Warships 1914–1919. Shepperton: Ian Allan. p. 34.

- ^ Dodson, Aidan (2024). "The Development of the British Royal Navy's Pennant Numbers Between 1919 and 1940". Warship International. 61 (2): 134–66.

- ^ Burt, pp. 75–76

- ^ a b c Preston 1972, p. 125

- ^ a b c d Burt, p. 76

- ^ Burt, pp. 76, 80

- ^ a b c Parkes, p. 503

- ^ Preston 1985, p. 23

- ^ Friedman, pp. 97–98

- ^ a b Burt, p. 81

- ^ Silverstone, p. 267

- ^ a b c d e f g Burt, p. 86

- ^ Corbett, p. 438

- ^ Massie, p. 19

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 32

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 163–165

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 172, 179, 183–184

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 190, 194–196, 206, 211–212

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 217–219, 221–222

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 228, 243, 246, 250, 253

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 271, 275, 279–280, 284, 286–290

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 54–55, 57–58

- ^ Burt, p. 86; Gordon, p. 416

- ^ Campbell, pp. 146, 157, 167, 205, 208, 232–234, 349

- ^ Halpern, pp. 330–332

- ^ Newbolt, pp. 235–238

Bibliography

- Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-863-7.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-324-5.

- ISBN 1-870423-50-X.

- ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- ISBN 978-1-59114-336-9.

- ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- OCLC 13614571.

- ISBN 0-679-45671-6.

- ISBN 0-89839-255-1.

- ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- ISBN 0-88365-300-1.

- Preston, Antony (1985). "Great Britain and Empire Forces". In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 1–104. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-917-8.