HMS Vanguard (1909)

Vanguard, 1910

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Vanguard |

| Ordered | 6 February 1908 |

| Builder | Vickers, Barrow-in-Furness |

| Laid down | 2 April 1908 |

| Launched | 22 February 1909 |

| Commissioned | 1 March 1910 |

| Fate | Sunk by internal explosion at Scapa Flow, 9 July 1917 |

| Notes | Protected war grave |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type | dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | 19,700 long tons (20,000 t) (normal) |

| Length | 536 ft (163.4 m) (o/a) |

| Beam | 84 ft (25.6 m) |

| Draught | 28 ft (8.5 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 × shafts; 2 × steam turbine sets |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 6,900 nmi (12,800 km; 7,900 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 753 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

HMS Vanguard was one of three

Shortly before midnight on 9 July 1917 at Scapa Flow, Vanguard suffered a series of magazine explosions. She sank almost instantly, killing 843 of the 845 men aboard. The wreck was heavily salvaged after the war, but was eventually protected as a war grave in 1984. It was designated as a controlled site under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986, and diving on the wreck is generally forbidden.

Design and description

The design of the

Vanguard was powered by two sets of

The St Vincent class was equipped with ten

The St Vincent-class ships were protected by a

Modifications

The guns on the forward turret roof were removed in 1910–1911. About three years later,

Construction and career

Vanguard, the eighth ship of that name to serve in the Royal Navy,

The ship was recommissioned on 28 March 1912 and rejoined the 1st Division shortly before it was renamed the

World War I

Between 17 and 20 July 1914, Vanguard took part in a test

Jellicoe's ships, including Vanguard, conducted gunnery drills west of Orkney and Shetland on 10–13 January 1915.[21] On the evening of 23 January, the bulk of the Grand Fleet sailed in support of Beatty's battlecruisers,[22] but they were too far away to participate in the ensuing Battle of Dogger Bank the following day. On 7–10 March, the Grand Fleet made a sweep in the northern North Sea, during which it conducted training manoeuvres. Another such cruise took place on 16–19 March. On 11 April, the fleet patrolled the central North Sea and returned to port on 14 April; another patrol in the area took place on 17–19 April, followed by gunnery drills off Shetland on 20–21 April.[23]

The Grand Fleet swept the central North Sea on 17–19 May and 29–31 May without encountering any German vessels. During 11–14 June the fleet practised gunnery and battle exercises west of Shetland,[24] and on 11 July there was more training off Shetland. On 2–5 September, the fleet went on another cruise in the northern end of the North Sea and conducted gunnery drills. Throughout the rest of the month, the Grand Fleet was performing numerous training exercises before making another sweep into the North Sea on 13–15 October. Almost three weeks later, Vanguard participated in another fleet training operation west of Orkney during 2–5 November.[25]

Captain James Dick relieved Hickley on 22 January 1916.[

Battle of Jutland

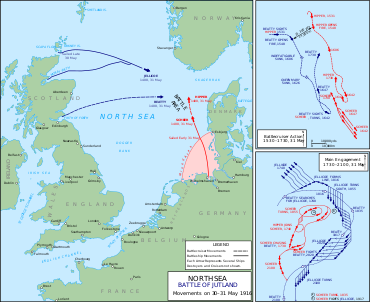

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet, composed of 16 dreadnoughts, 6 pre-dreadnoughts, and supporting ships, departed the Jade Bight early on the morning of 31 May. The fleet sailed in concert with Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper's five battlecruisers. The Royal Navy's Room 40 had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. In response the Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet, totalling some 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers, to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.[28]

During the Battle of Jutland on 31 May, Beatty's battlecruisers managed to bait Scheer and Hipper into a pursuit as they fell back upon the main body of the Grand Fleet. After Jellicoe deployed his ships into

Subsequent activity

The Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet, while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German

Explosion

The ship anchored in Scapa Flow at about 18:30 on 9 July 1917 after having spent the morning exercising general evolutions concluding practising the routine for abandoning ship. The Captain made a speech to the ship's company in which he stated that under present conditions a ship would either blow up in a matter of seconds, or would take several hours to sink. Practically this meant that all would go down with the ship or that everybody would be saved. It is a remarkable coincidence that his words were to be so tragically proved in less than 12 hours. There is no record of anyone detecting anything amiss until the first detonation at 23:20.

A

Although the explosion was obviously a detonation of the cordite charges in a main magazine, the reason for it was less clear. There were several theories. The inquiry found that some of the cordite on board, which had been temporarily offloaded in December 1916 and catalogued at that time, was past its stated safe life. The possibility of spontaneous detonation was raised, but could not be proved.[40] It was also noted that a number of ship's boilers were still in use, and some watertight doors, which should have been closed in wartime, were open as the ship was in port. It was suggested that this might have contributed to a dangerously high temperature in the magazines. The final conclusion of the court was that a fire started in a four-inch magazine, perhaps when a raised temperature caused spontaneous ignition of cordite, spreading to one or the other main magazines, which then exploded.[41]

Wreck

Vanguard's wreck was heavily salvaged in search of non-ferrous metals before it was declared a war grave in 1984. Some of the main armament and armour plate was also removed.

The wreck and its associated debris cover a large area and lies at a depth of approximately 34 metres (111 ft 7 in) at 58°51′24″N 3°06′22″W / 58.8566°N 3.1062°W. The amidships portion of the ship is almost completely gone and 'P' and 'Q' turrets were blown some 40 metres (130 ft) away. The bow and stern areas are almost intact as has been revealed by an extensive survey, carried out by a team of volunteer specialist divers and authorised by the Ministry of Defence in 2016.[38][42][43] A report of the survey was published in April 2018.[44]

The wreck was designated as a controlled site in 2002 and cannot be dived upon except with permission from the Ministry of Defence.[45] The centenary of Vanguard's loss was commemorated on 9 July 2017: descendants of the crew laid 40 wreaths above her wreckage, Royal Navy divers placed a new Union Jack on the wreck, and Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery—where some of the crew were buried—held a wreath-laying ceremony.[46]

See also

- List of United Kingdom disasters by death toll

Notes

- quick-firing QF Mark III guns. In addition, he lists a 12-pounder (three-inch (76 mm)) gun.[3] Preston 1972 concurs on the number of 4 inchers, but does not list the 12 pounder.[2] Parkes says twenty 4-inch guns; while not identifying the type, he does say they were 50-calibre guns[5] and Preston agrees.[6] Friedman shows the QF Mark III as a 40-calibre gun and says the 50-calibre BL Mark VII gun armed all the early dreadnoughts.[7]

- ^ Burt puts the cost at £1,606,030,[3] while Parkes quotes it as £1,607,780.[5]

- ^ In his 1919 book, Jellicoe generally only named specific ships when they were undertaking individual actions. Usually he referred to the Grand Fleet as a whole, or by squadrons and, unless otherwise specified, this article assumes that Vanguard is participating in the activities of the Grand Fleet.

- ^ The times used in this section are in UT, which is one hour behind CET, which is often used in German works.

Footnotes

- ^ Burt, pp. 75–76

- ^ a b c Preston 1972, p. 125

- ^ a b c d Burt, p. 76

- ^ Burt, pp. 76, 80

- ^ a b c Parkes, p. 503

- ^ Preston 1985, p. 23

- ^ Friedman, pp. 97–98

- ^ a b Burt, p. 81

- ^ Brooks, p. 168

- ^ Colledge, p. 369

- ^ "HMS Vanguard to be Commissioned To-morrow". Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser. 28 February 1910. Retrieved 13 January 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c d Burt, p. 86

- ^ "Arthur David Ricardo". The Dreadnought Project. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Medway Floating Dock". Portsmouth Evening News. 24 December 1912. Retrieved 13 January 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Items of Service News". Portsmouth Evening News. 5 June 1913. Retrieved 13 January 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Massie, p. 19

- ^ Preston 1985, p. 32

- ^ Naval Staff Monograph No. 24, pp. 40–41

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 143, 156, 163–165

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 172, 179, 183–184

- ^ Jellicoe, p. 190

- ^ Monograph No. 12, p. 224

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 194–196, 206, 211–212

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 217–219, 221–222

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 228, 243, 246, 250, 253

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 271, 275, 279–280

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 284, 286–290

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 54–55, 57–58

- ^ Corbett, frontispiece map and p. 428

- ^ Campbell, pp. 152, 157, 212, 349, 358

- ^ Halpern, pp. 330–332

- ^ Schleihauf, p. 69

- ^ Burt, p. 83

- ^ Saunders, Jonathan. "Vanguard's Casualties + Survivors". www.gwpda.org. The World War I Document Archive. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ "HMS Vanguard People: Scapa Flow Wrecks". www.scapaflowwrecks.com. Scapa Flow Historic Wreck Site. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ Schiefhauf, p. 60

- ^ Saunders, Jonathan. "HMS Vanguard – Lyness Casualties". The World War I Document Archive. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ a b "New Light is Shed on Disastrous Royal Navy Explosion in Scapa Flow". Naval Today. 20 January 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Schleihauf, pp. 61–62

- ^ Brown, p. 169

- ^ Burt, pp. 84, 86

- ^ "Scapa Flow Divers Reveal New Images of HMS Vanguard Wreck". Express Newspapers. 19 January 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "HMS Vanguard: Scapa Flow, Orkney (103004)". Canmore. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ "HMS Vanguard". Turton, E et al (2018) HMS Vanguard 100 Survey 2016–2017, Survey Report 2018.

- ^ "The Protection of Military Remains Act 1986 (Designation of Vessels and Controlled Sites) Order 2002". The National Archives. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ "Commemorating Centenary of Vanguard Disaster". Orkney Islands Council. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

Bibliography

- Brooks, John (1996). "Percy Scott and the Director". In McLean, David & Preston, Antony (eds.). Warship 1996. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 150–170. ISBN 0-85177-685-X.

- ISBN 1-55750-315-X.

- Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-863-7.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-324-5.

- ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- ISBN 1-870423-50-X.

- ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- OCLC 13614571.

- ISBN 0-679-45671-6.

- Monograph No. 12: The Action of Dogger Bank – 24th January 1915 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). Vol. III. The Naval Staff, Training and Staff Duties Division. 1921. pp. 209–226. OCLC 220734221.

- Monograph No. 24: Home Waters – Part II: September and October 1914 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). Vol. XI. The Naval Staff, Training and Staff Duties Division. 1924. OCLC 220734221.

- ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- ISBN 0-88365-300-1.

- Preston, Antony (1985). "Great Britain and Empire Forces". In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 1–104. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Schleihauf, William (July 2000). "Disaster in Harbour: The Loss of HMS Vanguard" (PDF). The Northern Mariner. X (3): 57–89. . Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-917-8.