Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard

Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

British India | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 14 June 1922 (aged 45) Gorhambury, Hertfordshire , England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | British | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Known for | Hunter, explorer, writer, cricketer, soldier | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cricket information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting | Right-handed | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling | Right-arm Bowler | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1900–1913 | Hampshire | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1902–1904 | London County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1904–1913 | Marylebone Cricket Club | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hesketh Vernon Prichard, later Hesketh-Prichard

He also explored territory never seen before by a European, played

His many activities brought him into the highest social and professional circles. Like other turn-of-the-century hunters such as Theodore Roosevelt (who was an admirer), he was an active campaigner for animal welfare and succeeded in seeing legal measures introduced for their protection.

Early life

Hesketh-Prichard was born an only child on 17 November 1876 in

Hesketh-Prichard and his mother returned to Great Britain soon after, and lived for a while at her parents' house, before moving to

Writing and exploration

First publications

Hesketh-Prichard, then nineteen, wrote his first story "Tammer's Duel" in the summer of 1896, which his mother helped him refine, and was sold soon after to

In 1897, he and his mother worked on the plot of A Modern Mercenary, the stories of Captain Rallywood, a dashing diplomat in Germany.[2] It was published by Smith and Elder the following year. He travelled to South America in February 1898, seeing the construction work for the Panama Canal, but returned after developing malaria while in the Caribbean.[7]

Commissioned trips

In 1899 Pearson chose Hesketh-Prichard to explore and report on the relatively unknown republic of Haiti, wanting something dramatic with which to launch his forthcoming Daily Express. Kate Prichard accompanied her son as far as Jamaica; in later years she would often travel with him to remote destinations in a time when it was uncommon for a woman of her age to do so. Hesketh-Prichard travelled extensively into the uncharted interior of Haiti, narrowly avoiding death when someone tried to poison him.[1] No white man was believed to have crossed the island since 1803, and his trip provided the first written description of some of the secret practices of "vaudoux" (voodoo).[8] He later wrote a vivid account of his travels in the popular book Where Black Rules White: A Journey Across and About Hayti.[9]

Pearson welcomed his reports, and on his return immediately commissioned him to travel to

Although he found no traces of the creature after a year overseas and 10,000 miles (16,000 km) of travel, he did provide compelling descriptions of unknown areas of the country, its fauna and inhabitants.

Labrador

Hesketh-Prichard first visited Atlantic Canada in August 1903, travelling up the coasts of Labrador and Newfoundland, and donating the heads of stags he had shot to the Newfoundland Exhibition then in London. He returned in October 1904, this time with his mother, and the cricketer Teddy Wynyard.[15] His most ambitious trip to the region was however in July 1910, when he undertook to explore the interior of Labrador, saying "it seemed to us a pity that such a terra incognita should continue to exist under the British flag".[16] This same territory had claimed the life of writer Leonidas Hubbard a few years earlier. He described his journey up the Fraser River to access Indian House Lake on George River in the popular Through Trackless Labrador in 1911.[16] His reputation was such that former President of the United States Theodore Roosevelt, a fellow writer, explorer and hunter, wrote to him, commending him on his latest book, which he described as the best that season, and asking to meet him.[17]

Further writing

In 1904, the mother-and-son writing team produced The Chronicles of Don Q., a collection of short stories featuring the fictional rogue Don Quebranta Huesos, a Spanish Robin Hood-like figure who was fierce to the evil rich but kind-hearted to the virtuous poor. A second collection, The New Chronicles of Don Q. followed in 1906. The pair produced a full-length novel, Don Q.'s Love Story, in 1909. Don Q. was brought to the stage in 1921 when it was performed at the Apollo Theatre, London.[18] In 1925, the book was reworked as a Zorro vehicle by screenwriters Jack Cunningham and Lotta Woods; the United Artists silent film Don Q, Son of Zorro was produced by Douglas Fairbanks, who also starred as its lead character.[19] The New York Times rated the film one of its top ten movies of the year.[20]

In 1913, writing on his own, Hesketh-Prichard created the crime-fighting figure November Joe, a hunter and backwoodsman from the Canadian wilderness.

Despite his reputation as a hunter, he campaigned to end the clubbing of

Cricket

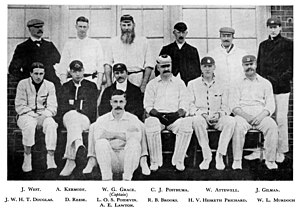

Hesketh-Prichard was a talented cricketer, who played for a number of major teams.

In the winter which followed the 1904 season, he

A tall man, he was able to use his height and reach to his advantage when bowling his right-arm fast deliveries, particularly in relation to his ability to exact quick bounce off the pitch.[27] In sixty first-class matches for Hampshire, he took 233 wickets at an average of 23.45, taking fifteen five wicket hauls and ten wickets in a match on four occasions.[30] His overall first-class career saw him play 86 matches, taking 339 wickets at an average of 22.37, with 25 five wicket hauls.[31] He was not however a strong batsman and would typically play in the tail of the batting order, scoring 724 runs across his first-class career at a batting average of 7.46.[31]

Military service

At the outbreak of the

Hesketh-Prichard was dismayed by the poor quality of

Innovations

He recognised German skill in constructing trench parapets: by making use of an irregular top and face to the parapet, and constructing it from material of varying composition, the presence of a sniper or an observer poking his head up became much less conspicuous. In contrast, British trench practice had been to give a military-straight neat edge to the parapet top, making any movement or protrusion immediately obvious.[36] An observer was vulnerable to an enemy sniper firing a bullet through his loophole, but Hesketh-Prichard devised a metal-armoured double loophole that would protect him. The front loophole was fixed, but the rear was housed in a metal shutter sliding in grooves. Only when the two loopholes were lined up—a one-to-twenty chance—could an enemy shoot between them.[37]

Another innovation was the use of a dummy head to find the location of an enemy sniper.[38] Initially, realistic papier-mâché heads were supplied to Hesketh-Prichard by the famous London theatrical wig and costume maker, Willy Clarkson.[39] These false heads were raised above the parapet on a stick running in a groove on a fixed board. To increase the realism, a lit cigarette could be inserted into the dummy's mouth and be smoked by a soldier via a rubber tube.[38] If the head was shot, it was dropped rapidly, simulating a casualty. The sniper's bullet would have made a hole in the front and back of the dummy's head. The head was then raised in the groove again, but lower than before by the vertical distance between the glasses of a trench periscope. If the lower glass of a periscope was placed before the front bullet hole, its upper glass would be at exactly the same height as the bullet had been. By looking through the rear hole in the head, through the front hole and up through the periscope, the soldier would be looking exactly along the line the bullet had taken, and so would be looking directly at the sniper, revealing his position.[38]

Training snipers

Hesketh-Prichard was eventually successful in gaining official support for his campaign, and in August 1915 was given permission to proceed with formalised sniper training.[40] By November of that year, his reputation was such that he was in high demand from many units. In December, he was ordered on General Allenby's request to the Third Army School of Instruction and was made a general staff officer with the rank of captain.[41] He was mentioned in dispatches on 1 January 1916.[42] In August 1916, he founded the First Army School of Sniping in the village of Linghem, Pas-de-Calais.[43] Starting with a first class of only six, in time he was able to lecture to large numbers of soldiers from different Allied nations, proudly proclaiming in a letter that his school was turning out snipers at three times the rate of any such other school in the world.[43] In October of that year he was awarded the Military Cross, the citation of which read:

- "For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He has instructed snipers in the trenches on many occasions, and in most dangerous circumstances, with great skill and determination. He has, directly and indirectly, inflicted enormous casualties on the enemy."[44]

His friend George Gray, himself a champion shooter, told him that he had reduced sniping casualties from five a week per battalion to forty-four in three months in sixty battalions; by his reckoning, this meant that Hesketh-Prichard had saved over 3,500 lives.[33] He was promoted to major in November 1916.[45] By this time in the war, his contributions to sniping had been such that the former German superiority in the practice had now been reversed.[26]

Later war years

Hesketh-Prichard was taken ill with an undetermined infection in late 1917 and was granted leave. His health remained poor for the rest of his life, and he spent much of it convalescing. It was during this period of leave that he learned that he had been awarded the Distinguished Service Order,[46] for his work with the First Army School of Sniping, Observation, and Scouting.[26] For his wartime work with the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps, he was appointed a Commander of the Military Order of Avis.[26][47] In 1920, he wrote his account of his wartime activities: the critically acclaimed Sniping in France, which is still referred to by modern authors on the subject.[48][49][50]

Later years

In July 1919, Hesketh-Prichard was elected Chairman of the Society of Authors, of which he had been a member for many years.[51] Poor health forced him to resign the following January.[52] Following his war service, he continued to write and hunt when his health permitted him.

Hesketh-Prichard died from

His mother survived him, dying in 1935.[26] His wife, who later became Woman of the Bedchamber to Queen Mary, lived until 1975.[55][56] Hesketh-Prichard's biography was written two years after his death by his friend Eric Parker, who encapsulated his many accomplishments within its title: Hesketh Prichard D.S.O., M.C.: Explorer, Naturalist, Cricketer, Author, Soldier.[3]

Family life

In 1908, Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard married Lady Elizabeth Grimston, the daughter of

References

- ^ JSTOR 1781332.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8047-1842-4.

- ^ a b Parker, Eric (1924). Hesketh Prichard. London: T. Fisher Unwin. pp. 12–13.

- ^ Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b c d e Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. pp. 36–42.

- ^ Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. pp. 45–50.

- ^ a b c d "PATAGONIA; Hesketh-Prichard's Stirring Tale of Exploration in the Far South". The New York Times. 20 December 1902. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ^ Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. pp. 61–64.

- ^ Pascual, M; et al. "Presencia de salmón chinook (Oncorhynchus Tshawytscha) en el Río Caterina, Estancia Cristina, Parque Nacional los Glaciares" (PDF) (in Spanish). Centro Nacional Patagónico. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 May 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ "Los Glaciares National Park". UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "Poa prichardii". Tropicos.org. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ^ Jacoby, Charlie (8 February 2001). "Giant Sloth". Daily Express. London. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ^ Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. pp. 71–75.

- ^ a b Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. pp. 97–98.

- ^ Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. p. 108.

- ^ a b Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. p. 243.

- IMDb. Accessed on 25 November 2008.

- ^ Hall, Mordaunt (10 January 1926). "Ten Best Films of 1925 Helped by Late Influx". The New York Times.

- ISBN 9781842432488. Archived from the originalon 19 December 2007.

- ^ "TV and Radio". The Times. London. 23 September 1970.

- ^ Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. pp. 114–115.

- ISBN 9780203440032.

- ^ Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. pp. 125–126.

- ^ doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/98115. Retrieved 28 November 2008. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^ a b c d "Obituaries in 1922". Wisden 1923. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "First-Class Matches played by Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d "First-Class Bowling in Each Season by Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "First-Class Bowling For Each Team by Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Player profile: Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard". ESPNcricinfo. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ a b c Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. pp. 157–162.

- ^ a b Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. pp. 251–254.

- ISBN 0850524261.

- ^ Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. p. 164.

- ^ Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. p. 171.

- ISBN 0-85052-426-1.

- ^ ISBN 0850524261.

- ISBN 9780199756711.

- ^ Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. p. 174.

- ^ Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. pp. 196–198.

- ^ "No. 29422". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 1915. pp. 1–5.

- ^ a b Parker, Eric. Hesketh Prichard. p. 212.

- ^ "No. 29824". The London Gazette (Supplement). 14 November 1916. p. 11055.

- ^ "No. 29934". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 February 1917. p. 1364.

- ^ "No. 30563". The London Gazette (Supplement). 8 March 1918. p. 2973.

- ^ "No. 31514". The London Gazette (Supplement). 19 August 1919. pp. 10613–10614.

- ^ Sniping in France by Major H. Hesketh-Prichard (1920)

- ISBN 9780312957667.

- ISBN 9780312362904.

- ^ "Authors' Society Dinner". The Times. 22 July 1919.

- ^ "Society of Authors". The Times. 27 January 1920.

- ISBN 9781551096582.

- ^ "Funerals: Major H.V. Hesketh-Prichard". The Times. London. 19 June 1922.

- ^ "Appointments to the Queen's Household". The Times. London. 31 December 1924.

- ^ "Lady Elizabeth Hesketh-Prichard". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- ISBN 978-1-86064-779-6.

- ^ Linasi, Marjan (2004). "Še o zavezniških misijah ali kako in zakaj je moral umreti britanski major Cahusac". Zgodovinski časopis. 57 (1–2): 99–116. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-7100-0573-1.

- ^ "A Wartime Mystery". Queens' College Record. 1998. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

Bibliography

- Hesketh-Prichard, Hesketh (1920). . ISBN 0850524261.

- Hesketh-Prichard, Hesketh (1902). Through the Heart of Patagonia. New York City: D. Appleton & Company.

- Hesketh-Prichard, Hesketh (1911). Through Trackless Labrador. London: Heinemann.

- Hesketh-Prichard, Hesketh (1900). Where Black Rules White: A journey across and about Hayti (PDF). New York City: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Parker, Eric (1924). Hesketh Prichard D.S.O., M.C.: Explorer, Naturalist, Cricketer, Author, Soldier:A Memoir. London: T. Fisher Unwin.

- Sweetman, Simon (2012). H.V. Hesketh-Prichard: Amazing Stories. ISBN 9781908165213.

External links

- Cricket

- Works by Hesketh-Prichard

- Works by Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Works by or about Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard at the Internet Archive

- Where Black rules white; a journey across and about Hayti, from Internet Archive

- Hunting camps in wood and wilderness, from Open Library

- Karadac, count of Gersay, from Open Library

- Through the Heart of Patagonia, from the Internet Archive

- Through Trackless Labrador, from Open Library

- Sniping in France, from Open Library

- November Joe: Backwoods detective, online copy of the out of copyright text

- Flaxman Low, Occult Psychologist, Collected Stories, Project Gutenberg Australia