Iberian nautical sciences, 1400–1600

Throughout the early age of exploration, it became increasingly clear that the residents of the Iberian Peninsula were experts at navigation, sailing, and expansion. From Henry the Navigator's first adventures down the African coast to Columbus's fabled expedition resulting in the discovery of the new world, the figures that catalyzed the European appetite for expansion and imperialism heralded from either Spain or Portugal. However, merely a century earlier, nautical travel for most peoples was resigned to keeping within sight of a coastline and very rarely did ships venture out into deeper waters. The period's ships were not able to handle the forces of open ocean travel and the crewmen had neither the ability nor the necessary materials to keep themselves from getting lost. A sailor's ability to travel was dictated by the technology available, and it was not until the late 15th century that the development of the nautical sciences on the Iberian Peninsula allowed for the genesis of long-distance shipping by directly effecting, and leading to the creation of, new tools and techniques relative to navigation. Christopher Columbus’s famous expedition, which crossed the ocean in 1492, was arguably the first contact the civilized world had with the newly discovered continent. Financed and sponsored by Queen Isabella of Spain, his journey would open the door to new trading lanes, imperialist appetites, and the meeting of cultures.[1] Portugal and Spain became the world's foremost leaders in deep water navigation and discovery because of their sailing expertise and the advancement of nautical sciences benefiting their ability to sail further, faster, more accurately, and safer than other states. Vast amounts of precious minerals and lucrative slaves were poured into Iberian treasuries between the late 15th and mid to late 17th centuries because of Spanish and Portuguese domination of Atlantic trade routes.[2] The golden age of Spain was a direct result of the advancements made in navigation technology and the sciences which allowed for deep water sailing.

To the population of Europe, trans-oceanic navigation was an almost inconceivably huge idea, yet the world would never be the same because a man with the simplest of tools managed to plot his way across the second largest body of water on the planet. Without those rudimentary yet extremely critical instruments, the ambitions of Columbus, along with his sponsoring state, would have been crushed. The development of nautical sciences, including the augmentation of pre-existing techniques and tools, on the Iberian Peninsula generated new technology and had a direct, visible, and lasting effect on long range ship board navigation.

| Iberian nautical sciences, 1400–1600 | |

|---|---|

| Duke of Viseu | |

Oporto, Portugal | |

| Died | 13 November 1460 (aged 66) Sagres, Algarve, Portugal |

| House | House of Aviz |

| Father | John I of Portugal |

| Mother | Philippa of Lancaster |

Prior to the 14th century, navigation by European sailors was a crude imitation of what was to come. The technology available was not suitable for anything more ambitious than coast hugging voyages to known landmasses. Captains were limited to technology developed centuries earlier, like the kamal of Arabian genesis, a crude instrument used to measure latitude, and ships with designs which prohibited their use due to the crushing swells, turbulent weather, and material attrition of an open ocean expedition. It was not until Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal was born in 1394 and gained influence at court through the 15th century that exploration and the development of nautical sciences became priorities under the Iberian governments.[4] Having been part of the campaign to capture Ceuta as a young man, Henry's world became ever larger as he traveled the world under the banner of Christ. Even though a zealous and sometimes violent Christian, he did not disregard tales he had heard of Arabian exploration and lands beyond what was known. He had heard about the voyages of Abufeda and Albyruny, two Arabian geographers, and their recollections of travel along the western coast of Africa and began to wonder where the continents of Europe and Africa ended.[5] The prince's mind was constantly intrigued. Henry wished to know how far the Muslim territories in Africa extended, and whether it was possible for him to reach the Orient by sea, both due to his desire to capitalize on the lucrative spice trade and pro-catholic sentiment.[6] Upon returning to Portugal, it was clear that his travels imprinted upon Henry the desire for further exploration and discovery, along with a desire to find a land “free of the Saracen”, which soon became clear as he took a more visible role in his father's court.

Prince Henry the Navigator's overwhelming desire to expand his knowledge of the known world directly led to the advancement of the nautical sciences. Having traveled extensively, it was not revelatory knowledge that the ships and tools available would not be adequate in order to fulfill expansionist and exploratory desires. He realized that his efforts would only be benefited by becoming an expert in, and patron of, the sciences. According to Martins, “He was a true scientist. He spent whole days and nights studying, experimenting … not speculating on the vague fanciful theories of theology or metaphysics, but seeking ever after … facts which could be applied to the everyday things of life.”[7] Reportedly he also lavished gifts upon visitors to court in the hopes of obtaining mysteries of navigation, seamanship, and knowledge of other countries.[8]

The town of a prince

Eventually founding a town on the extreme southwest coast at Cape St. Vincent which came to be called the Vila do Infante, or the Prince's Town, Henry attempted to concentrate the available nautical knowledge. Anchored in an area that seemed the gateway to the sea, the town was situated with the strait of Gibraltar to its south, the Mediterranean to its east, and the vast emptiness of the Atlantic to the west.[9] It was a perfect harbor within which to nurse the fledgling ideas of the age of exploration; the claim that the first rudimentary school for nautical navigation was located here is an invention of later centuries and has been debunked by Portuguese historians long ago. The dedication he had towards expanding the available knowledge, techniques, and tools available for exploration brought imperialist desires to the forefront of most major powers’ agenda and catalyzed the age of exploration, trade, empire, and cultural interaction that would follow.

During the time of Prince Henry and the following centuries, nautical science became the focus of many of Europe's most prominent experts in mathematics, astronomy, geography, meteorology, and physics. By applying their specific areas of expertise to the problems of seafaring navigation, many of the statutes of sailing and precursors to modern navigation were born. Up until the late 15th century, the most a sailor could rely on was his compass pointing north and experience. More accurate tools were not needed until the use of the caravel, a speedy vessel ideally suited to the ocean, became widespread. As sea travel became increasingly more important, sailors understood that the farther from coast they ventured, the more they would have to deal with currents, wind intensity and direction, star position based upon hemisphere, ship direction and speed.[10] The problems presented to exploration by the constantly shifting, always dangerous, and vastly infinite nature of the world's oceans were confronted and overcome by the development and application of nautical science.

The cross-staff

A pre-existing instrument was the

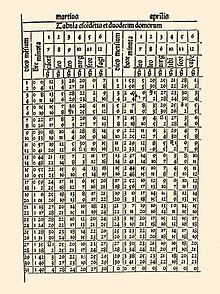

The more difficult part of celestial navigation was determining longitude; that problem was only resolved sufficiently in the 18th century. Early exploration therefore was restricted to using latitude as can be seen in latitude tables in early Portuguese nautical manuals (the socalled "Manuals" of Munich and Evora) and the data in log books ( for instance in the "roteiros" by Joao de Castro)

The quadrant

Another latitude-measuring instrument was the quadrant. Initially the quadrant was developed as an astronomical instrument and used in land based observatories. It was described by Ptolemy in the 1st century AD and later and used by Arab astronomers. In its later shape it consisted of either a wood or brass quarter circle with degrees marked along its lower edge; a length of string was attached to the upper point to serve as a plumb bob. The celestial object was then sighted through two sighting holes at the tip and the bottom and its height read off from the mark where the plumb bob passed the lower edge. Its nautical use must have started in the late 15th century; it is mentioned in the so-called "Diario" of Columbus.

The Mariner's astrolabe

The mariner's astrolabe also measured the altitude of celestial bodies; it was developed from the so-called planispheric astrolabe, an analogue computer to solve a set of astronomical problems. In contrast with the planispheric astrolabe the Mariner's astrolabe cannot perform calculations but only be used to obtain the height of a celestial object, ordinarily the sun because sighting stars or planets is practically impossible through the small sighting holes.

Whereas the planispheric astrolabe stems from antiquity the Mariner's Astrolabe was first depicted in a manuscript of 1517; the inventory of Magellan's voyage mentions several astrolabes made of wood and metal as well as wood. The instrument was discussed in all navigation manuals beginning in the mid-16th through the 17th century; it lost its prominent place in celestial navigation when the cross staff and the Davis quadrant gained general acceptance.

According to a census of 2018 more than 100 astrolabes are preserved, most of them salvaged from wrecks. Of these most are of Portuguese and Spanish ships that were lost on voyages to and from the East Indies (Portuguese) and the Spanish Main.

Pedro Nunes

The Portuguese mathematician

Abraham Zacuto and the ephemerides

Once out of sight of the coast, Portuguese and Spanish ship pilots could rely upon the astrolabe and quadrant to determine their location on a north–south reference, however longitude was noticeably more difficult to acquire. The problem was time. Out on the vast stretches of the ocean, it is very difficult to keep track of time once leaving port. In order to calculate longitude a sailor would need to know the time difference between his current location and a fixed point somewhere on earth, usually the port of call. Even if one could determine the time of day while in deep waters, they still needed to know the time at their home port. The answer was the

The nocturnal

The nocturnal was used to find the time at night using the north star. The observer would look through the central hole and align the movable arm with certain stars (the "guardas") of the Little Bear. The time could then be read at the outer rim. It was probably first described by Raimundud Lullius at the end of the 13th century; Peter Apian depicted it in 1514 in his "Cosmographicus Liber", so did Sebastian Mübster in 1537 in "Fürmalung und künstliche Bescheibung der Horologien (1537). Martín Cortés showed the nocturlabe for the first time in a nautical manual. There are many instruments preserved in museums and private collections which indicates its widespread use before the advent of more reliable time keepers.

Conclusion

However, none of these developments could have come about without a vigorous support of the sciences and the breakthroughs of numerous academics well versed in mathematics, physics, oceanography, and astronomy. Henry the Navigator, the catalyst for Portuguese exploration and imperialism, was himself an ardent and zealous student of the sciences. He may have invited cartographers and astronomers to Sagres in order to improve the science of navigation. The caravel and its deep water design rose to prominence under his patronage of the sciences and exploration. The court of his father was flooded with foreigners enticed by Henry and his appetite for any secrets of navigation they could provide. Although driven by religious motivation forged during the crusades, his influence on Portuguese exploration and patronage of nautical sciences is without doubt. Martín Cortés de Albacar and Abraham Zacuto both published works in the 16th century that became backbones for naval instruction through the end of the 19th century. Cortes's work included detailed instructions on how to both construct and apply an astrolabe while Zacuto's Almanach and the ephemerides published within were critical to the use of a nocturnal, notably by both Vasco da Gama and Pedro Álvares Cabral.

Without the advancements made in nautical sciences, particularly by Iberian scientists and explorers, trans-oceanic navigation would have not been possible. The earliest periods of navigation within Portugal and Spain employed the use of crude, antiquated, and unreliable instruments. The kamal and cross-staff, while both useful, lacked the ability to be consistently practically applied on board a ship. They were replaced by the trigonometric quadrant and its semi-circle construction. But even that was unreliable at times because a pilot would need calm waters in order to acquire a reading. Eventually it was used together with the astrolabe, which became a critical piece of equipment for navigation after Martín Cortés de Albacar published his Art. Because it could be used day or night, in rough or calm seas, it was cross referenced with the quadrant in order to gain the most accurate reading possible. Finally, the nocturnal and its accompanied values in the ephemerides granted sailors the ability to plot longitude on the open ocean. Navigation across vast stretches of open water was no longer merely as daunting. An expedition leader, the captains, ships, and crews could all be confident that, barring the intercession of the ocean's unpredictable nature, a course could be safely and accurately plotted from a port of call to final destination. Portugal to colonized Brazil, Spain to its holdings in Florida, the challenges of thousand mile and multiple month long excursions could be overcome. In the span of a few centuries, nautical sciences had granted man the ability to circumnavigate the globe by 1521, exploit vast reserves of untouched natural resources, open dialogue with previously unknown cultures, and open lucrative new trading routes; the world had become a much larger place.

See also

References

- ^ Paolo Emilio Taviani. Columbus, the Great Adventure: His Life, His Times, and His Voyages (New York: Orion Books), page 12

- ^ Fransisco Bethencourt, Portuguese Oceanic Expansion, 1400–1800 (Cambridge [England] : Cambridge University Press), page 113

- ^ The traditional image of the Prince presented in this page, and coming from the Saint Vincent Panels, is still under dispute.

- ^ Joaquinn Pedro Oliveira Martins, The Golden Age of Prince Henry the Navigator (New York: Dutton), page 62

- ^ Joaquinn Pedro Oliveira Martins, The Golden Age of Prince Henry the Navigator (New York: Dutton), page 68

- ^ Bailey Diffie, Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580 (Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press), page 121

- ^ Joaquinn Pedro Oliveira Martins, The Golden Age of Prince Henry the Navigator (New York: Dutton), page 65

- ^ John Dos Passos, The Portugal Story: Three Centuries of Exploration and Discovery. (Garden City, N.Y. : Doubleday), page 86

- ^ John Dos Passos, The Portugal Story: Three Centuries of Exploration and Discovery (Garden City, N.Y. : Doubleday), page 89

- ^ Bailey Diffie, Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press), page 118

- ^ Jeanne Willoz-Egnor, Cross-Staff

- ^ Bailey Diffie, Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press), page 142

- ^ Jones, S.S.D.; Howard, John; William, May; Logsdon, Tom; Anderson, Edward; Richey, Michael. "Navigation". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ a b Nissan Mindel, Rabbi Abraham Zacuto (1450–1515)