Mainstream economics

| Part of the behavioral sciences |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

|

Mainstream economics is the body of knowledge, theories, and models of

The economics profession has traditionally been associated with neoclassical economics.[1] However, this association has been challenged by prominent historians of economic thought including David Colander.[2] They argue the current economic mainstream theories, such as game theory, behavioral economics, industrial organization, information economics, and the like, share very little common ground with the initial axioms of neoclassical economics.

History

This section is missing information about Microeconomics. (June 2022) |

Economics has historically featured multiple schools of economic thought, with different schools having different prominence across countries and over time.[3]

Prior to the development and prevalence of classical economics, the dominant school in Europe was

During the Great Depression, the school of Keynesian economics gained attention as older models were neither able to explain the causes of the Depression nor provide solutions.[4] It built on the work of the underconsumptionist school, and gained prominence as part of the neoclassical synthesis, which was the post–World War II merger of Keynesian macroeconomics and neoclassical microeconomics that prevailed from the 1950s until the 1970s.[5]

In the 1970s, the consensus in macroeconomics collapsed as a result of the failure of the neoclassical synthesis to explain the phenomenon of

Over the course of the 1980s and the 1990s, macroeconomists coalesced around a paradigm known as the

The 2008 financial crisis and the ensuing Great Recession exposed modelling failures in the field of short-term macroeconomics.[12] While most macroeconomists had predicted the burst of the housing bubble, according to The Economist "they did not expect the financial system to break."[13]

Term

The term "mainstream economics" came into use in the late 20th century. It appeared in 2001 edition of the textbook

Scope

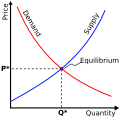

Mainstream economics can be defined, as distinct from other schools of economics, by various criteria, notably by its assumptions, its methods and its topics.

Assumptions

While being long rejected by many heterodox schools, several assumptions used to underpin many mainstream economic models. These include the neoclassical assumptions of

Originally, the starting point of orthodox economic analysis was the individual. Individuals and firms were generally defined as units with a common goal: maximisation through rational behaviour. The only differences consisted of:

- the specific objective of the maximisation (individuals tend to maximise utility and firms profit);[18]

- and the constraints faced in the process of maximisation (individuals might be constrained by limited income or commodity prices and firms might be constrained by technology or availability of inputs).[18]

From this (descriptive) theoretical framework, neoclassical economists like

Methods

Some economic fields include elements of both mainstream economics and heterodox economics: for example, institutional economics, neuroeconomics, and non-linear complexity theory.[20] They may use neoclassical economics as a point of departure. At least one institutionalist, John Davis, has argued that "neoclassical economics no longer dominates mainstream economics."[21]

Topics

Economics has been initially shaped as a discipline concerned with a range of issues revolving around money and wealth. However, in the 1930s, mainstream economics began to mutate into a science of human decision. In 1931, Lionel Robbins famously wrote "Economics is the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses". This drew a line of demarcation between mainstream economics and other disciplines and schools studying the economy.[22]

The mainstream approach of economics as a science of decision-making contributed to enlarge the scope of the discipline. Economists like

Notes

- ^ The precise distinction and relationship between classical economics and neoclassical economics is a debated point. Suffice to say that these are the ex post facto terms used to refer to successive chronological periods of an interrelated group of theories.

References

Footnotes

- ^ Colander 2000a, p. 35.

- ^ Colander 2000b, p. 130.

- ^ Dequech 2007, p. 279.

- ^ Jahan, Mahmud & Papageorgiou 2014, p. 53.

- ^ Blanchard 2016, p. 4.

- ^ Snowdon & Vane 2006, p. 23.

- ^ Snowdon & Vane 2006, p. 72.

- ^ Kocherlakota 2010, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Mankiw 2006, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Goodfriend & King 1997, pp. 231–232.

- ^ Woodford 2009, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Krugman 2009.

- ^ The Economist 2009.

- ^ Samuelson & Nordhaus 2001.

- ^ Blanchard 2016, p. 1.

- ^ Kaplan, Moll & Violante 2018, p. 699.

- ^ Kaplan, Moll & Violante 2018, p. 709.

- ^ a b Himmelweit 1997, p. 22.

- ^ Himmelweit 1997, p. 23.

- ^ Colander, Holt & Rosser 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Davis 2006, pp. 1, 4.

- ^ Schäfer & Schuster 2022, p. 11f.

- ^ Lazear 1999, p. 19.

- ^ Lazear 1999, p. 14.

- ^ a b Lazear 1999, p. 39.

- ^ Lazear 1999, p. 20.

- ^ Lazear 1999, p. 6.

Works cited

- ISBN 978-1-349-95121-5. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-631-22573-7.

- Clark, Barry Stewart (1998). Political economy: a comparative approach (2 ed.). Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-96370-5.

- OCLC 51977344.

- Colander, David; Holt, Richard P. F.; Rosser, Barkley J. Jr. (November 2003). "The Changing Face of Mainstream Economics" (PDF). Review of Political Economy. 16 (4): 485–499. S2CID 35411709.

- Colander, David (June 2000b). "The Death of Neoclassical Economics". Journal of the History of Economic Thought. 22 (2): 127–143. S2CID 154275191.

- Davis, John B. (1 April 2006). "The turn in economics: neoclassical dominance to mainstream pluralism?". Journal of Institutional Economics. 2 (1): 1–20. from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- Dequech, David (1 December 2007). "Neoclassical, Mainstream, Orthodox, and Heterodox Economics" (PDF). Journal of Post Keynesian Economics. 30 (2): 279–302. (PDF) from the original on 12 August 2017.

- JSTOR 3585232.

- Himmelweit, Sue (17 March 1997). "Chapter 2: The individual as the basic unit of analysis". In Green, Francis; Nore, Peter (eds.). Economics: An Anti-text. London: MacMillan. ISBN 9780765639233. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- Jahan, Sarwat; Mahmud, Ahmed Saber; Papageorgiou, Chris (September 2014). Hayden, Jeffrey; Primorac, Marina; et al. (eds.). "What Is Keynesian Economics?" (PDF). ISSN 0015-1947. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- Jelveh, Zubin; Kogut, Bruce; Naidu, Suresh (13 December 2022). "Political Language in Economics". SSRN Electronic Journal. SSRN 2535453. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- S2CID 31927674.

- S2CID 154126343. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- Krugman, Paul (2 September 2009). "How did economists get it so wrong?". The New York Times Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- Lazear, Edward P. (July 1999). "Economic Imperialism" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 115 (1) (published August 1999): 99–146. (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ISSN 0895-3309.

- "The other-worldly philosophers". ISSN 0013-0613.

- S2CID 154005964.

- ISBN 9780072509144.

- Schäfer, Georg N.; Schuster, Sören E. (7 June 2022). Mapping Mainstream Economics: Genealogical Foundations of Alternativity (1 ed.). London: Routledge. S2CID 249488205.

- Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard R. (2006). Modern macroeconomics: its origins, development and current state (PDF) (Reprinted Paperback ed.). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84542-208-0. Archived(PDF) from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.