Macroeconomics

| Part of a series on |

| Macroeconomics |

|---|

|

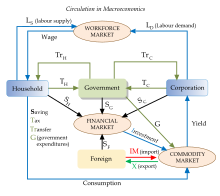

Macroeconomics is a branch of

Macroeconomics and microeconomics are the two most general fields in economics.[4] The focus of macroeconomics is often on a country (or larger entities like the whole world) and how its markets interact to produce large-scale phenomena that economists refer to as aggregate variables. In microeconomics the focus of analysis is often a single market, such as whether changes in supply or demand are to blame for price increases in the oil and automotive sectors. From introductory classes in "principles of economics" through doctoral studies, the macro/micro divide is institutionalized in the field of economics. Most economists identify as either macro- or micro-economists.

Macroeconomics is traditionally divided into topics along different time frames: the analysis of short-term fluctuations over the business cycle, the determination of structural levels of variables like inflation and unemployment in the medium (i.e. unaffected by short-term deviations) term, and the study of long-term economic growth. It also studies the consequences of policies targeted at mitigating fluctuations like fiscal or monetary policy, using taxation and government expenditure or interest rates, respectively, and of policies that can affect living standards in the long term, e.g. by affecting growth rates.

Macroeconomics as a separate field of research and study is generally recognized to start in 1936, when

Basic macroeconomic concepts

Macroeconomics encompasses a variety of concepts and variables, but above all the three central macroeconomic variables are output, unemployment, and inflation.

Time frame

It is usual to distinguish between three time horizons in macroeconomics, each having its own focus on e.g. the determination of output:[5]: 54

- the short run (e.g. a few years): Focus is on business cycle fluctuations and changes in aggregate demand which often drive them. Stabilization policies like monetary policy or fiscal policy are relevant in this time frame

- the medium run (e.g. a decade): Over the medium run, the economy tends to an output level determined by supply factors like the capital stock, the technology level and the labor force, and unemployment tends to revert to its structural (or "natural") level. These factors move slowly, so that it is a reasonable approximation to take them as given in a medium-term time scale, though competition policyare instruments that may influence the economy's structures and hence also the medium-run equilibrium

- the long run (e.g. a couple of decades or more): On this time scale, emphasis is on the determinants of long-run R&Dactivities.

Output and income

National output is the total amount of everything a country produces in a given period of time. Everything that is produced and sold generates an equal amount of income. The total net output of the economy is usually measured as gross domestic product (GDP). Adding net factor incomes from abroad to GDP produces gross national income (GNI), which measures total income of all residents in the economy. In most countries, the difference between GDP and GNI are modest so that GDP can approximately be treated as total income of all the inhabitants as well, but in some countries, e.g. countries with very large net foreign assets (or debt), the difference may be considerable.[5]: 385

Economists interested in long-run increases in output study economic growth. Advances in technology, accumulation of machinery and other

Unemployment

The amount of

Unemployment has a short-run cyclical component which depends on the business cycle, and a more permanent structural component, which can be loosely thought of as the average unemployment rate in an economy over extended periods,[6] and which is often termed the natural[6] or structural[7][5]: 167 rate of unemployment.

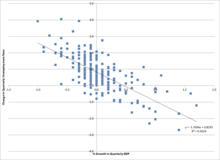

Cyclical unemployment occurs when growth stagnates. Okun's law represents the empirical relationship between unemployment and short-run GDP growth.[8] The original version of Okun's law states that a 3% increase in output would lead to a 1% decrease in unemployment.[9]

The structural or natural rate of unemployment is the level of unemployment that will occur in a medium-run equilibrium, i.e. a situation with a cyclical unemployment rate of zero. There may be several reasons why there is some positive unemployment level even in a cyclically neutral situation, which all have their foundation in some kind of market failure:[6]

- imperfect information, generally causing a time-consuming search and matching process when filling a job vacancy in a firm, during which the prospective worker will often be unemployed.[6][10] Sectoral shifts and other reasons for a changed demand from firms for workers with particular skills and characteristics, which occur continually in a changing economy, may also cause more search unemployment because of increased mismatch.[11][12][13]

- Efficiency wage models are labor market models in which firms choose not to lower wages to the level where supply equals demand because the lower wages would lower employees' efficiency levels[11]

- Trade unions, which are important actors in the labor market in some countries, may exercise market powerin order to keep wages over the market-clearing level for the benefice of their members even at the cost of some unemployment

- Legal monopsony power, however, employment effects may have the opposite sign.[15]

Inflation and deflation

A general price increase across the entire economy is called inflation. When prices decrease, there is deflation. Economists measure these changes in prices with price indexes. Inflation will increase when an economy becomes overheated and grows too quickly. Similarly, a declining economy can lead to decreasing inflation and even in some cases deflation.

Central bankers conducting monetary policy usually have as a main priority to avoid too high inflation, typically by adjusting interest rates. High inflation as well as deflation can lead to increased uncertainty and other negative consequences, in particular when the inflation (or deflation) is unexpected. Consequently, most central banks aim for a positive, but stable and not very high inflation level.[5]

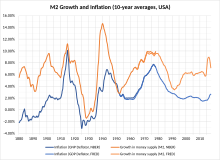

Changes in the inflation level may be the result of several factors. Too much

The

Open economy macroeconomics

Development

Macroeconomics as a separate field of research and study is generally recognized to start with the publication of

Before Keynes

In particular, macroeconomic questions before Keynes were the topic of the two long-standing traditions of

Keynes and Keynesian economics

When the Great Depression struck, the reigning economists had difficulty explaining how goods could go unsold and workers could be left unemployed. In the prevailing

In Keynes' theory,

The generation following Keynes combined the macroeconomics of the General Theory with neoclassical microeconomics to create the neoclassical synthesis. By the 1950s, most economists had accepted the synthesis view of the macroeconomy.[5]: 526 Economists like Paul Samuelson, Franco Modigliani, James Tobin, and Robert Solow developed formal Keynesian models and contributed formal theories of consumption, investment, and money demand that fleshed out the Keynesian framework.[5]: 527

Monetarism

Milton Friedman updated the quantity theory of money to include a role for money demand. He argued that the role of money in the economy was sufficient to explain the Great Depression, and that aggregate demand oriented explanations were not necessary. Friedman also argued that monetary policy was more effective than fiscal policy; however, Friedman doubted the government's ability to "fine-tune" the economy with monetary policy. He generally favored a policy of steady growth in money supply instead of frequent intervention.[5]: 528

Friedman also challenged the original simple Phillips curve relationship between inflation and unemployment. Friedman and Edmund Phelps (who was not a monetarist) proposed an "augmented" version of the Phillips curve that excluded the possibility of a stable, long-run tradeoff between inflation and unemployment.[20] When the oil shocks of the 1970s created a high unemployment and high inflation, Friedman and Phelps were vindicated. Monetarism was particularly influential in the early 1980s, but fell out of favor when central banks found the results disappointing when trying to target money supply instead of interest rates as monetarists recommended, concluding that the relationships between money growth, inflation and real GDP growth are too unstable to be useful in practical monetary policy making.[21]

New classical economics

Lucas also made an influential critique of Keynesian empirical models. He argued that forecasting models based on empirical relationships would keep producing the same predictions even as the underlying model generating the data changed. He advocated models based on fundamental economic theory (i.e. having an explicit microeconomic foundation) that would, in principle, be structurally accurate as economies changed.[5]: 530

Following Lucas's critique, new classical economists, led by

Despite criticism of the realism in the RBC models, they have been very influential in

New Keynesian response

By the late 1990s, economists had reached a rough consensus.[23] The market imperfections and nominal rigidities of new Keynesian theory was combined with rational expectations and the RBC methodology to produce a new and popular type of models called dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models. The fusion of elements from different schools of thought has been dubbed the new neoclassical synthesis.[24][25] These models are now used by many central banks and are a core part of contemporary macroeconomics.[5]: 535–36

After the global financial crisis

The

- the financial system and the nature of macrofinancial linkages and frictions, studying leverage, liquidity and complexity problems in the financial sector, the use of macroprudential tools and the dangers of an unsustainable public debt[5]: 537 [26]

- increased emphasis on empirical work as part of the so-called credibility revolution in economics, using improved methods to distinguish between correlation and causality to improve future policy discussions[27]

- interest in understanding the importance of HANK models), which may potentially also improve understanding of the impact of macroeconomics on the income distribution[28]

- understanding the implications of integrating the findings of the increasingly useful behavioral economics literature into macroeconomics[29] and behavioral finance

Growth models

Research in the economics of the determinants behind long-run

In the 1980s and 1990s endogenous growth theory arose to challenge the neoclassical growth theory of Ramsey and Solow. This group of models explains economic growth through factors such as increasing returns to scale for capital and learning-by-doing that are endogenously determined instead of the exogenous technological improvement used to explain growth in Solow's model.[35] Another type of endogenous growth models endogenized the process of technological progress by modelling research and development activities by profit-maximizing firms explicitly within the growth models themselves.[7]: 280–308

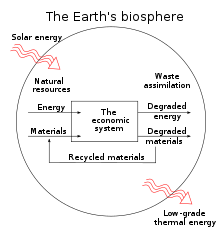

Environmental and climate issues

Since the 1970s, various environmental problems have been integrated into growth and other macroeconomic models to study their implications more thoroughly. During the oil crises of the 1970s when scarcity problems of natural resources were high on the public agenda, economists like

Macroeconomic policy

The division into various time frames of macroeconomic research leads to a parallel division of macroeconomic policies into short-run policies aimed at mitigating the harmful consequences of business cycles (known as stabilization policy) and medium- and long-run policies targeted at improving the structural levels of macroeconomic variables.[7]: 18

Stabilization policy is usually implemented through two sets of tools: fiscal and monetary policy. Both forms of policy are used to stabilize the economy, i.e. limiting the effects of the business cycle by conducting expansive policy when the economy is in a recession or contractive policy in the case of overheating.[5][38]

Structural policies may be labor market policies which aim to change the structural unemployment rate or policies which affect long-run propensities to save, invest, or engage in education or research and development.[7]: 19

Monetary policy

Via the

In developed countries, most central banks follow

Conventional monetary policy can be ineffective in situations such as a

Fiscal policy

Fiscal policy is the use of government's revenue (taxes) and expenditure as instruments to influence the economy.

For example, if the economy is producing less than potential output, government spending can be used to employ idle resources and boost output, or taxes could be lowered to boost private consumption which has a similar effect. Government spending or tax cuts do not have to make up for the entire output gap. There is a multiplier effect that affects the impact of government spending. For instance, when the government pays for a bridge, the project not only adds the value of the bridge to output, but also allows the bridge workers to increase their consumption and investment, which helps to close the output gap.

The effects of fiscal policy can be limited by partial or full crowding out. When the government takes on spending projects, it limits the amount of resources available for the private sector to use. Full crowding out occurs in the extreme case when government spending simply replaces private sector output instead of adding additional output to the economy. A crowding out effect may also occur if government spending should lead to higher interest rates, which would limit investment.[47]

Some fiscal policy is implemented through

Comparison of fiscal and monetary policy

There is a general consensus that both monetary and fiscal instruments may affect demand and activity in the short run (i.e. over the business cycle).

Macroeconomic models

Macroeconomic teaching, research and informed debates normally evolve around formal (

Well-known specific theoretical models include short-term models like the Keynesian cross, the IS–LM model and the Mundell–Fleming model, medium-term models like the AD–AS model, building upon a Phillips curve, and long-term growth models like the Solow–Swan model, the Ramsey–Cass–Koopmans model and Peter Diamond's overlapping generations model. Quantitative models include early large-scale macroeconometric model, the new classical real business cycle models, microfounded computable general equilibrium (CGE) models used for medium-term (structural) questions like international trade or tax reforms, Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models used to analyze business cycles, not least in many central banks, or integrated assessment models like DICE.

Specific models

IS–LM model

The

The IS curve consists of the points (combinations of income and interest rate) where investment, given the interest rate, is equal to public and private saving, given output.[51] The IS curve is downward sloping because output and the interest rate have an inverse relationship in the goods market: as output increases, more income is saved, which means interest rates must be lower to spur enough investment to match saving.[51]

The traditional LM curve is upward sloping because the interest rate and output have a positive relationship in the money market: as income (identically equal to output in a closed economy) increases, the demand for money increases, resulting in a rise in the interest rate in order to just offset the incipient rise in money demand.[52]

The IS-LM model is often used in elementary textbooks to demonstrate the effects of monetary and fiscal policy, though it ignores many complexities of most modern macroeconomic models.[49] A problem related to the LM curve is that modern central banks largely ignore the money supply in determining policy, contrary to the model's basic assumptions.[6]: 262 In some modern textbooks, consequently, the traditional IS-LM model has been modified by replacing the traditional LM curve with an assumption that the central bank simply determines the interest rate of the economy directly.[6]: 194 [5]: 113

AD-AS model

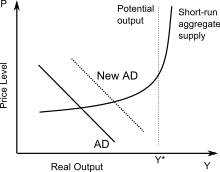

The AD–AS model is a common textbook model for explaining the macroeconomy.[53] The original version of the model shows the price level and level of real output given the equilibrium in aggregate demand and aggregate supply. The aggregate demand curve's downward slope means that more output is demanded at lower price levels.[54] The downward slope can be explained as the result of three effects: the Pigou or real balance effect, which states that as real prices fall, real wealth increases, resulting in higher consumer demand of goods; the Keynes or interest rate effect, which states that as prices fall, the demand for money decreases, causing interest rates to decline and borrowing for investment and consumption to increase; and the net export effect, which states that as prices rise, domestic goods become comparatively more expensive to foreign consumers, leading to a decline in exports.[54]

In many representations of the AD–AS model, the aggregate supply curve is horizontal at low levels of output and becomes inelastic near the point of potential output, which corresponds with full employment.[53] Since the economy cannot produce beyond the potential output, any AD expansion will lead to higher price levels instead of higher output.

In modern textbooks, the AD–AS model is often presented sligthly differently, however, in a diagram showing not the price level, but the inflation rate along the vertical axis,

See also

Notes

- ^ Samuelson, Robert (2020). "Goodbye, readers, and good luck — you'll need it". The Washington Post. This article was an opinion piece expressing despondency in the field shortly before his retirement, but it is still a good summary.

- ISBN 978-0-13-063085-8.

- ^ Steve Williamson, Notes on Macroeconomic Theory, 1999

- ISBN 978-0-521-31644-6

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Blanchard (2021).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Romer (2019).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sørensen and Whitta-Jacobsen (2022).

- ^ Dwivedi, 445–46.

- ^ "Neely, Christopher J. "Okun's Law: Output and Unemployment. Economic Synopses. Number 4. 2010".

- ^ Dwivedi, 443.

- ^ a b c d Mankiw (2022).

- ^ "Freeman (2008)".

- ^ Dwivedi, 444–45.

- ^ Pettinger, Tejvan. "Involuntary unemployment". Economics Help. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- S2CID 7012497.

- ^ Mankiw 2022, p. 98.

- . Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d Dimand (2008).

- ^ Snowdon and Vane (2005).

- ^ "Phillips Curve: The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics | Library of Economics and Liberty". www.econlib.org. Retrieved 2018-01-23.

- S2CID 219465676.

- ^ The role of imperfect competition in new Keynesian economics, Chapter 4 of Surfing Economics by Huw Dixon

- ^ Blanchard (2009).

- JSTOR 3585232. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ISSN 1945-7707. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ISSN 0022-0515. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Nakamura and Steinsson (2018) write that macroeconomics struggles with long-term predictions, which is a result of the high complexity of the systems it studies.

- ^ Guvenen, Fatih. "Macroeconomics with Heterogeneity: A Practical Guide" (PDF). www.nber.org. National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Ji, Yuemei; De Grauwe, Paul (1 November 2017). "Behavioural economics is also useful in macroeconomics". CEPR. Centre for Economic Policy Research. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-349-95121-5.

- ISBN 978-1-349-95121-5.

- ^ Banton, Caroline. "The Neoclassical Growth Theory Explained". Investopedia. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- ^ Solow 2002, pp. 518–19.

- ^ Solow 2002, p. 519.

- ^ Blaug 2002, pp. 202–03.

- ISBN 9780444594877. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ Harris J. (2006). Environmental and Natural Resource Economics: A Contemporary Approach. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ^ a b Mayer, 495.

- ^ Baker, Nick; Rafter, Sally (16 June 2022). "An International Perspective on Monetary Policy Implementation Systems | Bulletin – June 2022". Reserve Bank of Australia. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ISBN 978-92-9259-298-1.

- ^ "Federal Reserve Board - Monetary Policy: What Are Its Goals? How Does It Work?". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 29 July 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Fixed exchange rate policy". Nationalbanken. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ "Inflation Targeting: Holding the Line". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ Ingves, Stefan (12 May 2011). "Flexible inflation targeting in theory and practice" (PDF). www.bis.org. Bank of International Settlements. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ISBN 979-8-4002-3526-9. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ Hancock, Diana; Passmore, Wayne (2014). "How the Federal Reserve's Large-Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs) Influence Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) Yields and U.S. Mortgage Rates" (PDF). www.federalreserve.gov. Federal Reserve. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Arestis, Philip; Sawyer, Malcolm (2003). "Reinventing fiscal policy" (PDF). Levy Economics Institute of Bard College (Working Paper, No. 381). Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-349-95121-5. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ a b Durlauf & Hester 2008.

- ^ Peston 2002, pp. 386–87.

- ^ a b Peston 2002, p. 387.

- ^ Peston 2002, pp. 387–88.

- ^ a b Healey 2002, p. 12.

- ^ a b Healey 2002, p. 13.

References

- Blanchard, Olivier. (2009). "The State of Macro." Annual Review of Economics 1(1): 209–228.

- Blanchard, Olivier (2021). Macroeconomics (Eighth, global ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-134-89789-9.

- Blaug, Mark (2002). "Endogenous growth theory". In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard (eds.). An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84542-180-9.

- Dimand, Robert W. (2008). "Macroeconomics, origins and history of". In Durlauf, Steven N.; Blume, Lawrence E. (eds.). The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 236–44. ISBN 978-0-333-78676-5.

- Durlauf, Steven N.; Hester, Donald D. (2008). "IS–LM". In Durlauf, Steven N.; Blume, Lawrence E. (eds.). The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 585–91. ISBN 978-0-333-78676-5.

- Dwivedi, D.N. (2001). Macroeconomics: theory and policy. New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-058841-7.

- Gärtner, Manfred (2006). Macroeconomics. Pearson Education Limited. ISBN 978-0-273-70460-7.

- Healey, Nigel M. (2002). "AD-AS model". In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard (eds.). An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 11–18. ISBN 978-1-84542-180-9.

- Levi, Maurice (2014). The Macroeconomic Environment of Business (Core Concepts and Curious Connections). New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 978-981-4304-34-4.

- Mankiw, Nicholas Gregory (2022). Macroeconomics (Eleventh, international ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers, Macmillan Learning. ISBN 978-1-319-26390-4.

- Mayer, Thomas (2002). "Monetary policy: role of". In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard R. (eds.). An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 495–99. ISBN 978-1-84542-180-9.

- Nakamura, Emi and Jón Steinsson. (2018). "Identification in Macroeconomics." Journal of Economic Perspectives 32(3): 59–86.

- Peston, Maurice (2002). "IS-LM model: closed economy". In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard R. (eds.). An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics. Edward Elgar. ISBN 9781840643879.

- Romer, David (2019). Advanced macroeconomics (Fifth ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-1-260-18521-8.

- Solow, Robert (2002). "Neoclassical growth model". In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard (eds.). An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 1840643870.

- Snowdon, Brian, and Howard R. Vane, ed. (2002). An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics, Description & scroll to Contents-preview links.

- Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard R. (2005). Modern Macroeconomics: Its Origins, Development And Current State. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 1845421809.

- Sørensen, Peter Birch; Whitta-Jacobsen, Hans Jørgen (2022). Introducing advanced macroeconomics: growth and business cycles (Third ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-885049-6.

- Warsh, David (2006). Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05996-0.

Further reading

- Glandon, P. J., Ken Kuttner, Sandeep Mazumder, and Caleb Stroup. 2023. "Macroeconomic Research, Present and Past." Journal of Economic Literature, 61 (3): 1088-1126.