Martin Luther (1953 film)

| Martin Luther | |

|---|---|

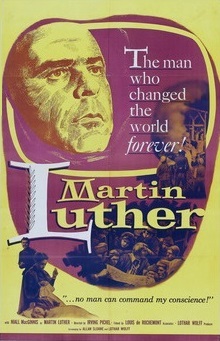

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Irving Pichel |

| Written by | |

| Produced by | Lothar Wolff |

| Starring | Niall MacGinnis |

| Cinematography | Joseph C. Brun |

| Edited by | Fritz Stapenhorst |

| Music by | Mark Lothar |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Countries | United States West Germany |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $350,000[2]—$500,000[3] |

| Box office | $3 million[2] |

Martin Luther is a 1953 biographical film of Martin Luther. It was directed by Irving Pichel (who also plays a supporting role) and stars Niall MacGinnis as Luther. It was produced by Louis de Rochemont and RD-DR Corporation in collaboration with Lutheran Church Productions and Luther-Film-G.M.B.H.

A notice at the beginning of the film characterizes it as a careful and balanced presentation of Luther's story: "This dramatization of a decisive moment in human history is the result of careful research of facts and conditions in the 16th century as reported by historians of many faiths." The research was done by notable Reformation scholars Theodore G. Tappert and Jaroslav Pelikan who assisted Allan Sloane and Lothar Wolff.

The National Board of Review named the film the fourth best of 1953. It was nominated for two Oscars, for Best Cinematography (Black-and-White) (Joseph C. Brun) and Art Direction/Set Decoration (Black-and-White) (Fritz Maurischat, Paul Markwitz).[4] The music was composed by Mark Lothar and performed by the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra. It was filmed at the Wiesbaden Studios in Hesse, West Germany.

The film was commercially very successful.[3]

Summary

The time frame of the film is 1505–1530: Luther's entrance into

Plot

During the life of Martin Luther power is divided between the Holy Roman Empire and the Roman Catholic Church. The narrator states: "the church had largely forgotten the mercies of God and, instead, it emphasized God's implacable judgments."

Before entering St. Augustine's Monastery, Martin Luther holds a party with his fellow law students.

Returning from Rome, Luther opines that the common people could more easily find God merciful if the Holy Scriptures were in their vernacular. He is scolded by his prior. Luther meets George Spalatin, who has also left law for the church: in his case to serve Frederick III, Elector of Saxony. Spalatin asks if Luther has found what he was looking for. Luther responds, "Not yet." Spalatin recommends Luther to the Elector as professor of Biblical studies at the University of Wittenberg. Luther baptizes an infant in the castle church.

Luther receives his

In 1517

In 1519

The pope is furious with Luther's publications of 1520 (

At Worms Luther is asked if he acknowledges his writings and whether he will retract any of them. Luther answers that he will not recant, saying, "Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me. Amen." Emperor Charles V outlaws Luther, giving him twenty-one days to return to Wittenberg. Elector Frederick has Luther quietly abducted to the Wartburg near Eisenach where Luther stays in hiding for almost a year. Here he translates the New Testament into German.

Luther's exile ends with Karlstadt's uprising in Wittenberg and the

Cast

- Niall MacGinnis as Martin Luther

- John Ruddock as Vicar Johann von Staupitz

- Pierre Lefevre as George Spalatin

- Guy Verney as Philipp Melanchthon

- Allastair Hunter as Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt

- David Horne as Elector Duke Frederick the Wise

- Fred Johnson as Prior of Erfurt monastery

- Philip Leaver as Pope Leo X

- Heinz Piper as Dr. John Eck

- Leonard Whiteas brother and emissary of Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz

- Egon Strohm as Cardinal Aleander

- Annette Carell as Katharina von Bora

- John Tetzel

- Brueck

- Hans Lefebre as Emperor Charles V

- John Wiggin as Narrator

- Henry Oscar

- Ronald Adam

- Joss Ambler

- William Abney

- Michael Maick

- Wolfgang Oelze

Historical inconsistencies

- Pope Julius II is represented as being in Rome when Luther was there when, in reality, he was not.

- Tetzel is represented as saying that no confession was necessary when one bought the indulgences he was selling when, in reality, the indulgences specified that the buyer was to go to confession if he had bought the indulgence for himself.

- Luther's 1520 treatises are represented as having been in print by June 15, 1520 when Exsurge Domine was issued when, in reality, they had not.

- Luther is represented as telling Karlstadt to leave Wittenberg in 1522 when, in reality, Luther pleaded with him in Orlamünde to return after Karlstadt had voluntarily left.

- Luther is represented as being at home in Wittenberg during the Diet of Augsburg in 1530 when, in reality, he was staying in Coburg.

- The isometric form of "A Mighty Fortress Is Our God" did not exist in Luther's time; It was a product of the later Pietistic movement which found fault with early rhythmic chorale melodies because their dance-like rhythms were too secular in nature.

Reception

The film received positive reviews from critics. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times praised the film as "a brilliant demonstration of strongly disciplined emotions and intellects," with dialogue "done with such forceful delivery and in such well-staged and well-assembled scenes that it commands intelligent attention and stimulates the mind."[5] Variety wrote: "An artistic achievement of its kind, reflecting careful research and preparation, boasting a magnificent performance by Niall MacGinnis, of London's Old Vic, in the title role, and given reverential, straightforward, honest, sincere treatment, as well as eschewing anything savoring of sensationalism, it is well calculated to stir the enthusiasm of Lutheran and Protestant ministers along with the more devoted laity."[6] Harrison's Reports called the picture "tops" and thought the entire cast did "superb work."[7] John McCarten of The New Yorker wrote that every player in the cast "commands attention," and thought that the documentary-like film techniques were used "to good advantage."[8] The Monthly Film Bulletin found the film increasingly "tedious" as there was "no dramatic structure as such," but nonetheless concluded, "That the film was made at all, however, and that its honesty and truth hold their own for so long, is as remarkable as creditable."[9]

Censorship

The film failed to be approved by

References

- ^ "Martin Luther". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ a b "'Schweitzer' Documentary to be Sold a La 'Luther". Variety. 13 March 1957. p. 19.

- ^ a b "'Luther' Winds up Theatrical Run". Variety. 31 August 1957. p. 7.

- ^ "NY Times: Martin Luther". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-03-21. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (September 10, 1953). "The Screen: Two Films Make Debut". The New York Times: 22.

- ^ "'Martin Luther,' Under Church Auspices, Looks OK Theatre B.O. Also". Variety: 6. May 13, 1953.

- ^ "'Martin Luther' with Niall MacGinnis". Harrison's Reports: 154. September 26, 1953.

- ^ McCarten, John (September 19, 1953). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. pp. 108–109.

- ^ "Martin Luther". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 21 (251): 173. December 1954.

- ^ "Lutherans Protest 'Martin Luther' Ban". The New York Times. January 1, 1954. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ Canadian Press (January 1, 1954). "Toronto, Dec. 31". The New York Times. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ Community Besieged: The Anglophone Minority and the Politics of Quebec By Garth Stevenson, page 52

- ^ "Film Censorship", The Canadian Encyclopedia

External links

- Martin Luther at IMDb

- Martin Luther at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Martin Luther at the TCM Movie Database

- Martin Luther is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive