Palace of Aachen

50°46′32″N 6°05′02″E / 50.77556°N 6.08389°E

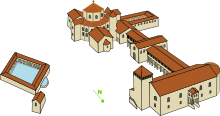

The Palace of Aachen was a group of buildings with residential, political, and religious purposes chosen by Charlemagne to be the center of power of the Carolingian Empire. The palace was located north of the current city of Aachen, today in the German Land (or state) of North Rhine-Westphalia. Most of the Carolingian palace was built in the 790s but the works went on until Charlemagne's death in 814. The plans, drawn by Odo of Metz, were part of the program of renovation of the kingdom decided by the ruler. Today much of the palace is ruined, but the Palatine Chapel has been preserved and is considered a masterpiece of Carolingian architecture and a characteristic example of architecture from the Carolingian Renaissance.

Historical context

The palace before Charlemagne

In

The choice of Aachen

The site of Aachen was chosen by Charlemagne after careful consideration in a key moment of his reign.

Aachen's geographic location was a decisive factor in Charlemagne's choice: the site was situated in the Carolingian heartlands of

Besides, settling down in Aachen enabled Charlemagne to control the operations in Saxony from a closer position.[7] Charlemagne also considered other advantages of the place: surrounded with forest abounding in game, he intended to abandon himself to hunting in the area.[8] The ageing emperor could also benefit from Aachen's hot springs.

The scholars of the Carolingian era presented Charlemagne as the "New

Importance of the project entrusted to Odo of Metz

Historians know almost nothing about the architect of the Palace of Aachen,

The decision to build the palace was taken in the late 780s or the early 790s, before Charlemagne held the title of emperor. Works began in 794[13] and went on for several years. Aachen quickly became the favourite residence of the sovereign. After 807, he almost did not leave it any more. In the absence of sufficient documentation, it is impossible to know the number of workers employed, but the dimensions of the building make it probable that there were many of them.

The geometry of the plan chosen was very simple: Odo of Metz decided to keep the layout of the Roman roads and inscribe the square in 360 Carolingian

The arrival of the court in Aachen and the construction work stimulated the activity in the city that experienced growth in the late 8th century and the early 9th century, as craftsmen, traders and shopkeepers had settled near the court. Some important ones lived in houses inside the city. The members of the Palace Academy and Charlemagne's advisors such as

Council Hall

Located at the North of the Palace complex, the great Council Hall (

The dimensions of the hall (1,000 m2) were suitable to the reception of several hundreds of people at the same time:

Palatine Chapel

Description

The Palatine Chapel was located at the other side of the palace complex, at the South. A stone gallery linked it to the aula regia. It symbolized another aspect of Charlemagne's power, religious power. Legend has it that the building was consecrated in 805 by

Several buildings used by the clerics of the chapel were arranged in the shape of a

The two additional floors (

Charlemagne wanted his chapel to be magnificently decorated, so he had massive bronze doors made in a foundry near Aachen. The walls were covered with marble and polychrome stone.[25] The columns, still visible today, were taken from buildings in Ravenna and Rome, with the Pope's permission.

The walls and cupola were covered with

[...] Hence it was that he [Charlemagne] built the beautiful basilica at Aachen, which he adorned with gold and silver and lamps, and with rails and doors of solid brass. He had the columns and marbles for this structure brought from Rome and Ravenna, for he could not find such as were suitable elsewhere. [...] He provided it with a great number of sacred vessels of gold and silver and with such a quantity of clerical robes that not even the doorkeepers who fill the humblest office in the church were obliged to wear their everyday clothes when in the exercise of their duties.[26]

Symbolism

Other buildings

Treasury and archives

The

The

Gallery

The covered gallery was a hundred meters long. It linked the council hall to the chapel; a monumental porch in its middle was used as the main entrance. A room for legal hearing was located on the second floor. The king dispensed justice in this place, although affairs in which important people were involved were handled in the aula regia. When the king was away, this task fell on the count of the Palace. The building was also probably used as a garrison.[3]

Thermae

The

[...] [Charlemagne] enjoyed the exhalations from natural warm springs, and often practised swimming, in which he was such an adept that none could surpass him; and hence it was that he built his palace at Aix-la-Chapelle, and lived there constantly during his latter years until his death. He used not only to invite his sons to his bath, but his nobles and friends, and now and then a troop of his retinue or body guard, so that a hundred or more persons sometimes bathed with him.[26]

Other buildings for other functions

The other buildings are not easy to identify because of the lack of detailed enough written accounts. Charlemagne's and his family's apartments seem to have been located in the north-eastern part of the palace complex; his room may have been on the second floor.

The palace also housed the literary activities of the Palace Academy. This circle of scholars did not gather in a definite building: Charlemagne liked to listen to poems while he was swimming and eating. The Palace school provided education to the ruler's children and the "nourished ones" (nutriti in Latin), aristocrat sons that were to serve the king.

Outside of the palace complex were also a

The place was frequented everyday by crowds of people: courtiers, scholars, aristocrats, merchants but also beggars and poor people that came to ask for

Symbolic interpretation of the Palace

Roman legacy and Byzantine model

The palace borrows several elements of Roman civilization. The Aula Palatina follows a basilical plan.

Charlemagne wished to compete with another Emperor of his time: Basileus of Constantinople.[9] The cupola and mosaics of the chapel are Byzantine elements. The plan itself is inspired by the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, built by Justinian I in the 6th century. Other experts point to similarities with the Church of the Saints Sergius and Bacchus, Constantinople's Chrysotriklinos and the main throne room in the Great Palace of Constantinople. During religious offices, Charlemagne stood in the second floor gallery, as did the Emperor in Constantinople.[3]

Odo of Metz was also likely inspired by the 8th-century Lombard Palace of Pavia where the chapel was decorated with mosaics and paintings.[17] Although he may have travelled to Italy, it is unlikely that he visited Constantinople.

Frankish style

Although many references to Roman and Byzantine models are visible in Aachen's buildings,

Charlemagne's palace was thus more than a copy of Classical and Byzantine models: it was rather a synthesis of various influences, as a reflection of the Carolingian Empire. Just like Carolingian Renaissance, the palace was a product of the assimilation of several cultures and legacies.

Imperial centralization and unity

The layout of the palatine complex perfectly implemented the alliance between two powers: the spiritual power was represented by the chapel in the South and the temporal power by the Council Hall in the North. Both of these were linked by the gallery. Since

After Charlemagne

Model for other palaces

It is difficult to know whether other Carolingian palaces did imitate that of Aachen, as most of them have been destroyed. However, the constructions of Aachen were not the only ones undertaken under Charlemagne: 16

Palace history after Charlemagne

Charlemagne was buried in the chapel in 814. His son and successor,

Following the

Yet the memory of Charlemagne's Empire remained fresh and became a symbol of German power. In the 10th century,

[...] The bronze eagle, that Charlemagne had put on top of the palace in a flight attitude, has been turned back towards the East. The Germans had turned it towards the West to show that their cavalry could beat the French whenever they wanted [...].[45]

In 881, a

Between 1355 and 1414, an

See also

- Aachen

- Carolingian art

- Carolingian Empire

- Palatine Chapel in Aachen

Notes

- ^ a b A. Erlande-Brandeburg, A.-B. Erlande-Brandeburg, Histoire de l’architecture française, 1999, p. 104

- ^ a b J. Favier, Charlemagne, 1999, p. 285

- ^ a b c d e f g h P. Riché, La vie quotidienne dans l’Empire Carolingian, p. 57

- ^ A. Erlande-Brandeburg, A.-B. Erlande-Brandeburg, Histoire de l’architecture française, 1999, p. 92

- ^ J. Favier, Charlemagne, 1999, p. 582

- ^ J. Favier, Charlemagne, 1999, p. 287

- ^ A. Erlande-Brandeburg, A.-B. Erlande-Brandeburg, Histoire de l’architecture française, 1999, pp. 92–93

- ^ a b c G. Démians d’Archimbaud, Histoire artistique de l’Occident médiéval, 1992, p. 76

- ^ a b P. Riché, Les Carolingiens. Une famille qui fit l’Europe, 1983, p. 326

- ^ M. Durliat, Des barbares à l’an Mil, 1985, p. 145

- ^ J. Favier, Charlemagne, 1999, p. 288

- ^ J. Favier, Charlemagne, 1999, p. 502

- ISBN 978-2729812317, p. 184

- ^ A Carolingian foot corresponds to 0,333 metres

- ^ a b c A. Erlande-Brandeburg, A.-B. Erlande-Brandeburg, Histoire de l’architecture française, 1999, p. 103

- ^ P. Riché, Les Carolingiens …, 1983, p. 325

- ^ ISBN 2-200-26577-8, p. 120

- ^ a b c d e f P. Riché, La vie quotidienne dans l’Empire carolingien, p. 58

- ^ Ermold le Noir, Poème sur Louis le Pieux et épîtres au roi Pépin, édité et traduit par Edmond Faral, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1964, p. 53

- ^ P. Riché, Les Carolingiens. Une famille qui fit l’Europe, 1983, p. 131

- ^ A porch surrounded with two stair towers, la forerunner of Westworks

- ISBN 2-85229-971-2, p. 1888

- ^ J. Favier, Charlemagne, 1999, p. 505

- ^ G. Démians d’Archimbaud, Histoire artistique de l’Occident médiéval, 1992, p. 81

- ^ A. Erlande-Brandeburg, A.-B. Erlande-Brandeburg, Histoire de l’architecture française, 1999, p. 127

- ^ a b Source : Einhard: "The Life of Charlemagne", translated by Samuel Epes Turner (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1880). http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/einhard.html

- ^ Apocalypse, XXI, 17. Read online at Wikisource (French).

- ISBN 2-200-21883-4, p. 136

- ISBN 2-213-03180-0, p. 244

- ^ A. Erlande-Brandeburg, A.-B. Erlande-Brandeburg, Histoire de l’architecture française, 1999, p. 105

- ^ G. Démians d’Archimbaud, Histoire artistique de l’Occident médiéval, 1992, p. 78

- ^ existence is attested by Eginhard, Life of Charlemagne, traduction et édition de Louis Halphen, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1994, p. 99

- ^ J. Favier, Charlemagne, 1999, p. 513

- ISBN 2-213-03180-0, p. 243

- ISBN 2-913944-63-9

- ^ G. Démians d’Archimbaud, Histoire artistique de l’Occident médiéval, 1992, p. 80

- ^ J. Favier, Charlemagne, 1999, p. 592

- ISBN 2-253-13056-7, p. 287

- ISBN 2-85229-971-2, p. 1888

- ^ M. Durliat, Des barbares à l’an Mil, 1985, p. 148

- ^ P. Riché, La vie quotidienne dans l’Empire carolingien, p. 59

- ISBN 2-200-21883-4, p. 35

- ISBN 2-200-21883-4, p. 40

- ^ P. Riché, Les Carolingiens. Une famille qui fit l’Europe, 1983, p. 247

- ^ Richer, Histoire de France (888–995), tome 2, edition and translation by Robert Latouche, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1964, p. 89

- ^ J. Favier, Charlemagne, 1999, p. 590

- ^ J. Favier, Charlemagne, 1999, p. 691

References

- Alain Erlande-Brandeburg, Anne-Bénédicte Erlande-Brandeburg, Histoire de l’architecture française, tome 1 : du Moyen Âge à la Renaissance, IVe – XVIe siècle, 1999, Paris, éditions du Patrimoine, ISBN 2-85620-367-1.

- Gabrielle Démians D’Archimbaud, Histoire artistique de l’Occident médiéval, Paris, Colin, 3e édition, 1968, 1992, ISBN 2-200-31304-7.

- Marcel Durliat, Des barbares à l’an Mil, Paris, éditions citadelles et Mazenod, 1985, ISBN 2-85088-020-5.

- Jean Favier, Charlemagne, Paris, Fayard, 1999, ISBN 2-213-60404-5.

- Jean Hubert, Jean Porcher, W. F. Volbach, L’empire carolingien, Paris, Gallimard, 1968

- Félix Kreush, « La Chapelle palatine de Charlemagne à Aix », dans Les Dossiers d'archéologie, n°30, 1978, pages 14–23.

- Pierre Riché, La Vie quotidienne dans l’Empire carolingien, Paris, Hachette, 1973

- Pierre Riché, Les Carolingiens. Une famille qui fit l’Europe, Paris, Hachette, 1983, ISBN 2-01-019638-4.

External links

![]() Media related to Palace of Aachen at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Palace of Aachen at Wikimedia Commons

- (in French) Aachen cathedral in pictures