Palimpsest

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2014) |

In

Etymology

The word palimpsest derives from

Development

Because parchment prepared from animal hides is far more durable than paper or papyrus, most palimpsests known to modern scholars are parchment, which rose in popularity in Western Europe after the 6th century. Where papyrus was in common use, reuse of writing media was less common because papyrus was cheaper and more expendable than costly parchment. Some papyrus palimpsests do survive, and Romans referred to this custom of washing papyrus.[note 1]

The writing was washed from parchment or

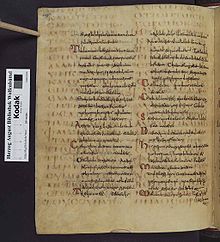

Medieval codices are constructed in "gathers" which are folded (compare folio, 'leaf, page' ablative case of Latin folium), then stacked together like a newspaper and sewn together at the fold. Prepared parchment sheets retained their original central fold, so each was ordinarily cut in half, making a quarto volume of the original folio, with the overwritten text running perpendicular to the effaced text.

Modern decipherment

Faint legible remains were read by eye before 20th-century techniques helped make lost texts readable. To read palimpsests, scholars of the 19th century used chemical means that were sometimes very destructive, using tincture of gall or, later, ammonium bisulfate. Modern methods of reading palimpsests using ultraviolet light and photography are less damaging.

Innovative digitized images aid scholars in deciphering unreadable palimpsests. Superexposed photographs exposed in various light spectra, a technique called "multispectral filming", can increase the contrast of faded ink on parchment that is too indistinct to be read by eye in normal light. For example, multispectral imaging undertaken by researchers at the Rochester Institute of Technology and Johns Hopkins University recovered much of the undertext (estimated to be more than 80%) from the Archimedes Palimpsest. At the Walters Art Museum where the palimpsest is now conserved, the project has focused on experimental techniques to retrieve the remaining text, some of which was obscured by overpainted icons. One of the most successful techniques for reading through the paint proved to be X-ray fluorescence imaging, through which the iron in the ink is revealed. A team of imaging scientists and scholars from the United States and Europe is currently using spectral imaging techniques developed for imaging the Archimedes Palimpsest to study more than one hundred palimpsests in the library of Saint Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt.[5]

Recovery

A number of ancient works have survived only as palimpsests.

Texts most susceptible to being overwritten included obsolete legal and liturgical ones, sometimes of intense interest to the historian. Early Latin translations of Scripture were rendered obsolete by Jerome's

Vast destruction of the broad quartos of the early centuries took place in the period which followed the fall of the Western Roman Empire, but palimpsests were also created as new texts were required during the Carolingian Renaissance. The most valuable Latin palimpsests are found in the codices which were remade from the early large folios in the 7th to the 9th centuries. It has been noticed that no entire work is generally found in any instance in the original text of a palimpsest, but that portions of many works have been taken to make up a single volume. An exception is the Archimedes Palimpsest (see below). On the whole, early medieval scribes were thus not indiscriminate in supplying themselves with material from any old volumes that happened to be at hand.

Famous examples

- The best-known palimpsest in the legal world was discovered in 1816 by Niebuhr and Savigny in the Institutes of Gaius, probably the first students' textbook on Roman law.[6]

- The Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris: portions of the Old and New Testaments in Greek, attributed to the 5th century, are covered with works of Ephraem the Syrianin a hand of the 12th century.

- The Carbon dating of the parchment assigns a date somewhere before 671 with a probability of 99%. Given that sūra 9, one of the last revealed chapters, is present and assuming the likely possibility that the undertext (the scriptio inferior) was written shortly after the preparation of the parchment, it was probably written relatively shortly, 10 to 40 years, after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. The undertext differs from the standard Qur'anic text and is therefore the most important documentary evidence for the existence of variant Qur'anic readings.[7]

- Among the Syriac manuscripts obtained from the Add. Ms. 17212with Syriac translation of St. Chrysostom's Homilies, of the 9th/10th century, covers a Latin grammatical treatise from the 6th century.

- Codex Nitriensis, a volume containing a work of Severus of Antioch of the beginning of the 9th century, is written on palimpsest leaves taken from 6th-century manuscripts of the Iliad and the Gospel of Luke, both of the 6th century, and the Euclid's Elements of the 7th or 8th century, British Museum.

- A double palimpsest, in which a text of St. John Chrysostom, in Syriac, of the 9th or 10th century, covers a Latin grammatical treatise in a cursive hand of the 6th century, which in its turn covers the Latin annals of the historian Granius Licinianus, of the 5th century, British Museum.

- The only known hyper-palimpsest: the Novgorod Codex, where potentially hundreds of texts have left their traces on the wooden back wall of a wax tablet.

- The Ambrosian Plautus, in rustic capitals, of the 4th or 5th century, re-written with portions of the Bible in the 9th century, Ambrosian Library.

- uncials, of the 4th century, the sole surviving copy, covered by St. Augustine on the Psalms, of the 7th century, Vatican Library.

- Seneca, On the Maintenance of Friendship, the sole surviving fragment, overwritten by a late-6th-century Old Testament.

- The Codex Theodosianus of Turin, of the 5th or 6th century.

- The Fasti Consulares of Verona, of 486.

- The Arian fragment of the Vatican, of the 5th century.

- The letters of Cornelius Fronto, overwritten by the Acts of the Council of Chalcedon.

- The Archimedes Palimpsest, a work of the great Syracusan mathematician copied onto parchment in the 10th century and overwritten by a liturgical text in the 12th century.

- The Sinaitic Palimpsest, the oldest Syriac copy of the gospels, from the 4th century.

- The unique copy of a Greek grammatical text composed by Herodian for the emperor Marcus Aurelius in the 2nd century, preserved in the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

- Zante, by General Colin Macaulay, deciphered, transcribed and edited by Tregellesin 1861.

- The Codex Dublinensis (Codex Z) of St. Matthew's Gospel, at Trinity College Dublin, also deciphered by Tregelles in 1853.

- The Codex Guelferbytanus 64 Weissenburgensis, with text of Origins of Isidore, partly palimpsest, with texts of earlier codices Guelferbytanus A, Guelferbytanus B, Codex Carolinus, and several other texts Greek and Latin.

- The Jerusalem Palimpsest of Euripides contains fragments of the text of Euripides. Among these fragments, six plays are included: Hecuba, Phoenissae, Orestes, Andromacha, Hippolytus and Medea.[8]

About sixty palimpsest manuscripts of the Greek New Testament have survived to the present day.

Porphyrianus, Vaticanus 2061 (double palimpsest), Uncial 064, 065, 066, 067, 068 (double palimpsest), 072, 078, 079, 086, 088, 093, 094, 096, 097, 098, 0103, 0104, 0116, 0120, 0130, 0132, 0133, 0135, 0208, 0209.

Lectionaries include:

- Lectionary 226, ℓ 1637.cvd

See also

- Palimpsest (disambiguation) for other uses of the word

- Pentimento

- Petroglyphs of Arpa-Uzen – rock art from the Bronze and Iron Ages later covered by Saka pictorials

Notes

- ^ According to Suetonius, Augustus, "though he began a tragedy with great zest, becoming dissatisfied with the style, he obliterated the whole; and his friends saying to him, What is your Ajax doing? He answered, My Ajax met with a sponge." (Augustus, 85). Cf. a letter of the future emperor Marcus Aurelius to his friend and teacher Fronto (ad M. Caesarem, 4.5), in which the former, dissatisfied with a piece of his own writing, facetiously exclaims that he will "consecrate it to water (lymphis) or fire (Volcano)," i.e. that he will rub out or burn what he has written.

- ^ The most accessible overviews of the transmission of texts through the cultural bottleneck are Leighton D. Reynolds (editor), in Texts and Transmission: A Survey of the Latin Classics, where the texts that survived, fortuitously, only in palimpsest may be enumerated, and in his general introduction to textual transmission, Scribes and Scholars: A Guide to the Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature (with N.G. Wilson).

References

- ISBN 978-1-60606-083-4.

- ^ Page-Phillips, John (1980). Palimpsests - the backs of monumental brasses.

- ISBN 978-90-04-19318-5.

- ISBN 978-019-516122-9.

- ^ "In the Sinai, a global team is revolutionizing the preservation of ancient manuscripts". Washington POST Magazine. September 8, 2012. Archived from the original on 2021-05-13. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- OCLC 800515546.

- (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-24. Retrieved 2012-03-26.

- ISBN 9783110011937. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

External links

- OPIB Virtual Renaissance Network activities in digitizing European palimpsests

- Brief note on economic and cultural considerations in production of palimpsests

- PBS NOVA: "The Archimedes Palimpsest" Click on "What is a Palimpsest?"

- Rinascimento virtuale a project for the census, description, study and digital reproduction of Greek palimpsests

- Ángel Escobar, El palimpsesto grecolatino como fenómeno librario y textual, Zaragoza 2006

- Jost Gippert, Exploring Armenian Palimpsests with Multispectral and Transmissive Light Imaging