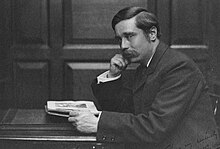

Political views of H. G. Wells

H. G. Wells (1866–1946) was a prolific English writer in many genres, including the novel, history, politics, and social commentary, and textbooks and rules for war games. Wells called his political views socialist.

The Fabian Society

Wells was for a time a member of the Fabian Society, a socialist organization, but broke with them as his creative political imagination, matching the originality shown in his fiction, outran theirs.[1] He later grew staunchly critical of them as having a poor understanding of economics and educational reform, but remained committed to socialist ideals. He ran as a Labour Party candidate for London University in the 1922 and 1923 general elections after the death of his friend W. H. R. Rivers, but at that point his faith in the party was weak or uncertain.[citation needed]

Class

Social class was a theme in Wells's The Time Machine in which the Time Traveller speaks of the future world, with its two races, as having evolved from

the gradual widening of the present (19th century) merely temporary and social difference between the Capitalist and the Labourer ... Even now, does not an East-end worker live in such artificial conditions as practically to be cut off from the natural surface of the earth? Again, the exclusive tendency of richer people ... is already leading to the closing, in their interest, of considerable portions of the surface of the land. About London, for instance, perhaps half the prettier country is shut in against intrusion.[2]

Wells has this very same Time Traveller, reflecting his own socialist leanings, refer in a tongue-in-cheek manner to an imagined world of stark

Once, life and property must have reached almost absolute safety. The rich had been assured of his wealth and comfort, the toiler assured of his life and work. No doubt in that perfect world there had been no unemployed problem, no social question left unsolved.[2]

In his book

Democracy

World government

His most consistent political ideal was the

Eugenics

Some of Wells's early science fiction works reflect his thoughts about the degeneration of humanity.[9] Wells doubted whether human knowledge had advanced sufficiently for eugenics to be successful. In 1904, he discussed a survey paper by Francis Galton, co-founder of eugenics, saying, "I believe that now and always the conscious selection of the best for reproduction will be impossible; that to propose it is to display a fundamental misunderstanding of what individuality implies... It is in the sterilisation of failure, and not in the selection of successes for breeding, that the possibility of an improvement of the human stock lies". In his 1940 book The Rights of Man: Or What are we fighting for? Wells included among the human rights he believed should be available to all people, "a prohibition on mutilation, sterilization, torture, and any bodily punishment".[10]

Race

In 1901, Wells wrote Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress Upon Human Life and Thought, which included the following extreme views:

And how will the new republic treat the inferior races? How will it deal with the black? how will it deal with the yellow man? How will it tackle that alleged termite in the civilized woodwork, the Jew? Certainly not as races at all. It will aim to establish, and it will at last, though probably only after a second century has passed, establish a world state with a common language and a common rule. All over the world its roads, its standards, its laws, and its apparatus of control will run. It will, I have said, make the multiplication of those who fall behind a certain standard of social efficiency unpleasant and difficult… The Jew will probably lose much of his particularism, intermarry with Gentiles, and cease to be a physically distinct element in human affairs in a century or so. But much of his moral tradition will, I hope, never die. … And for the rest, those swarms of black, and brown, and dirty-white, and yellow people, who do not come into the new needs of efficiency?

Well, the world is a world, not a charitable institution, and I take it they will have to go. The whole tenor and meaning of the world, as I see it, is that they have to go. So far as they fail to develop sane, vigorous, and distinctive personalities for the great world of the future, it is their portion to die out and disappear.

The world has a greater purpose than happiness; our lives are to serve God's purpose, and that purpose aims not at man as an end, but works through him to greater issues.[11]

Wells's 1906 book

show any thing finer than the quality of the resolve, the steadfast effort hundreds of black and coloured men are making to-day to live blamelessly, honourably, and patiently, getting for themselves what scraps of refinement, learning, and beauty they may, keeping their hold on a civilization they are grudged and denied.[12]

In his 1916 book What is Coming?, Wells states, "I hate and despise a shrewish suspicion of foreigners and foreign ways; a man who can look me in the face, laugh with me, speak truth and deal fairly, is my brother, though his skin is as black as ink or as yellow as an evening primrose".[14]

In The Outline of History, Wells argued against the idea of "racial purity", stating: "Mankind from the point of view of a biologist is an animal species in a state of arrested differentiation and possible admixture . . . [A]ll races are more or less mixed.".[15]

In 1931, Wells was one of several signatories to a letter in Britain (along with 33 British MPs) protesting against the death sentence passed upon the African American Scottsboro Boys.[16]

In 1943, Wells wrote an article for the Evening Standard, "What A Zulu thinks of the English", prompted by receiving a letter from a Zulu soldier, Lance Coporal Aaron Hlope.[17][18][19] "What a Zulu thinks of the English" was a strong attack on anti-black discrimination in South Africa. Wells claimed he had "the utmost contempt and indignation for the unfairness of the handicaps put upon men of colour". Wells also denounced the South African government as a "petty white tyranny".[17][18][19]

Wells had given some moderate, unenthusiastic support for

First World War

He supported Britain in the First World War,[24] despite his many criticisms of British policy, and opposed, in 1916, moves for an early peace.[25] In an essay published that year he acknowledged that he could not understand those British pacifists who were reconciled to "handing over great blocks of the black and coloured races to the [German Empire] to exploit and experiment upon" and that the extent of his own pacifism depended in the first instance upon an armed peace, with "England keep[ing] to England and Germany to Germany". State boundaries would be established according to natural ethnic affinities, rather than by planners in distant imperial capitals, and overseen by his envisaged world alliance of states.[26]

In his book In the Fourth Year published in 1918 he suggested how each nation of the world would elect, "upon democratic lines" by proportional representation, an electoral college in the manner of the United States of America, in turn to select its delegate to the proposed League of Nations.[27] This international body he contrasted with imperialism, not only the imperialism of Germany, against which the war was being fought, but also the imperialism, which he considered more benign, of Britain and France.[28] His values and political thinking came under increasing criticism from the 1920s and afterwards.[29]

Soviet Union

The leadership of

Monarchy

Wells was a republican[32] and an advocate for the creation of republican clubs in the UK.[33] In 1914, Wells referred to the United Kingdom as a crowned republic.[34]

Other endeavours

Wells brought his interest in Art & Design and politics together when he and other notables signed a memorandum to the Permanent Secretaries of the Board of Trade, among others. The November 1914 memorandum expressed the signatories concerns about British industrial design in the face of foreign competition. The suggestions were accepted, leading to the foundation of the Design and Industries Association.[35] In the 1920s he was an enthusiastic supporter of rejuvenation attempts by Eugen Steinach and others. He was a patient of Dr Norman Haire (perhaps a rejuvenated one) and in response to Haire's 1924 book Rejuvenation: the Work of Steinach, Voronoff, and others,[36] Wells prophesied a more mature, graver society with 'active and hopeful children' and adults 'full of years' where none will be 'aged'.[37]

In his later political writing, Wells incorporated into his discussions of the World State a notion of universal human rights that would protect and guarantee the freedom of the individual. His 1940 publication The Rights of Man laid the groundwork for the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[38]

Summary

In the end Wells's contemporary political impact was limited, excluding his fiction's positivist stance on the leaps that could be made by

References

- ISBN 0-7100-7866-8.

- ^ a b "The Time Machine". Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ H. G. Wells, The Way the World is Going. London, Ernest Benn, 1928, (p. 49).

- ^ a b Siegel, Fred (2013). The Revolt Against the Masses. New York: Encounter Books, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Wells, H. G. The Open Conspiracy: Blue Prints for a World Revolution (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1928), (pp. 28, 44, 196).

- ISBN 0679438092(p. 21–22).

- S2CID 145676493.

- ISBN 0754633837, (p. 16).

- ^ "H. G. Wells and the uses of Degeneration in Literature". Bbk.ac.uk. 1946-08-17. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- ISBN 9780199205523(pp. 29-31).

- ^ Wells, HG (1902). Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress Upon Human Life and Thought (2nd ed.). Chapman & Hall. pp. 316–318.

- ^ a b H. G. Wells, The Future in America (New York and London: Harper and Brothers, 1906), p. 201 (Chs.11 & 12,).

- ISBN 0813011825. (p. 150, 231)

- ^ What is Coming? A Forecast of things after the war, London, Cassell, 1916 (p. 256).

- ^ H. G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), p. 110 (Ch. XII, §§1–2).

- ISBN 0691088284, (p. 29).

- ^ a b "What a Zulu Thinks of the English" was reprinted as "The Rights of Man in South Africa" '42 to '44: A Contemporary Memoir (London, Secker and Warburg, 1944) (p. 68–74).

- ^ ISBN 0945636059, (p. 247).

- ^ ISBN 0816188564(p. 176,177, 179)

- ^ Cheyette, Bryan. Constructions of "the Jew" in English Literature and Society. Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 143–148

- ^ Hamerow, Theodore S. Why we watched: Europe, America, and the Holocaust. W. W. Norton & Company, 2008, pp. 98–100, 219

- ^ "Desirable Aliens: British Men of Letters on The Jews". The Review of Reviews Vol. XXXIII Jan–Jun 1906, p. 378

- ISBN 9781846554964.

- ^ H. G. Wells: Why Britain Went To War (10 August 1914). The War Illustrated album de luxe. The story of the great European war told by camera, pen and pencil. The Amalgamated Press, London 1915

- ^ Daily Herald, 27 May 1916

- OCLC 9446824.

- OCLC 458935146.

The president ... is chosen by a special college elected by the people .... Is there any reason why we should not adopt this method in this sending representatives to the Council of the League of Nations?

- ^ "The Necessary Powers of the League". In the Fourth Year.

[T]he League of Free Nations, if it is to be a reality ... must do no less than supersede Empire; it must end not only this new German imperialism, which is struggling so savagely and powerfully to possess the earth, but it must also wind up British imperialism and French imperialism, which do now so largely and inaggressively possess it.

- ^ Experiment in Autobiography 556. Also chapter four of Future as Nightmare: H. G. Wells and the Anti-Utopians by Mark Robert Hillegas.

- ^ Experiment in Autobiography, pp. 215, 687–689

- ^ "Joseph Stalin and H. G. Wells, Marxism vs. Liberalism: An Interview". Rationalrevolution.net. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ISBN 1475917503(p. 338)

- ^ "From the archive: Mr HG Wells on the issue of monarchy". The Guardian. 1917-04-22.

- ^ "64. The British Empire in 1914. Wells, H.G. 1922. A Short History of the World". www.bartleby.com. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ Raymond Plummer, Nothing Need be Ugly Design & Industries Assn. Jun 1985

- ^ Haire, Norman (1924), Rejuvenation : the work of Steinach, Voronoff, and others, G. Allen & Unwin, retrieved 15 April 2013

- ^ Diana Wyndham. "Norman Haire and the Study of Sex". Foreword by the Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG. Sydney: "Sydney University Press"., 2012, p. 117

- ^ ‘Human Rights and Public Accountability in H. G. Wells’ Functional World State’ | John Partington. Academia.edu. Retrieved on 9 August 2013.